Liftoff: Elon Musk and the Desperate Early Days That Launched SpaceX

by

Eric Berger

Published 2 Mar 2021

“It was like having two children,” Musk said. “I could not bring myself to let one of the companies die.” In Musk’s worldview, he could not let either venture go. Tesla was needed to save Earth from climate change, helping to break humans from their fossil fuel addiction. And SpaceX would offer a backup plan by making humanity a multiplanetary species. He split his money between the two companies. Amid these bleak financial times, SpaceX had one final card to play. In 2006, NASA had come through with critical funding for the company after the failure of the first Falcon 1, betting that SpaceX would eventually figure out how to reach orbit.

…

His argument for reuse is simple: If an airline discarded a 747 jet after every transcontinental flight, passengers would have to pay $1 million for a ticket. Similarly, if every rocket flown into space drops into the ocean, space will remain cost prohibitive for all but a few wealthy nations and a few exclusive astronauts. To make humanity a multiplanetary species, Musk sought to lower the cost of getting into space and flying onward to other worlds. The early returns on the reuse experiment were, nonetheless, sobering. “We were very naive at the time, but the expectation was that we would throw a parachute on this thing and recover it,” Musk said.

…

And when they did that, the Department of Defense realized that they could either be a part of that, or they could be left behind.” So many people like Chinnery felt burned out by their years at SpaceX because Musk pushed them relentlessly. His schedules were invariably aggressive. Time was money. This window to reach Mars and make humanity a multiplanetary species, Musk fears, may not remain open forever. And Musk’s own lifetime was finite. This brutal devotion to speed got results. The first Falcon 1 launch attempt came a mere three years and ten months after Musk started SpaceX. The company reached “space” in four years and ten months. It made orbit in six years and four months.

The Space Barons: Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, and the Quest to Colonize the Cosmos

by

Christian Davenport

Published 20 Mar 2018

“When I was a kid I found the slideshows kind of tedious, but maybe it stuck in some way. Now I’d like to see the slideshow. But as a kid I was, like, ‘I want to go play with my friends. Why are you showing me these slides of the desert?’” In founding SpaceX, Musk believed that in addition to trying to make humans a multiplanetary species—with the ultimate goal of sending people to Mars—he saw space travel as the greatest adventure ever, even greater than the quixotic searches for the Lost City. Although there was, as he said, the “defensive reason” to go to Mars to colonize another planet—so that humanity would have another place to go in case anything happened to Earth—this was not what inspired him to go to Mars.

…

Now Elon—always the one name—was the new face of the American space program, the embodiment of exploration, a modern-day amalgam of JFK and Neil Armstrong, with 10 million Twitter followers. The press room in Guadalajara was overflowing with reporters who had come from all over the world for this long-awaited speech, titled “Making Humans a Multiplanetary Species,” in which Musk would, finally, lay out his plan to colonize Mars. In the months leading up to Guadalajara, he disclosed some of the details, telling the Washington Post that he intended to build a transportation system to the Red Planet like the railroads that traversed the United States, with the goal of the first humans landing on Mars in 2025.

…

After the launch, an emotional Musk called it “an incredible milestone in the history of space,” one that SpaceX had been working toward for fifteen years. This, he said, would be what would ultimately lower the cost of spaceflight, perhaps by a factor of a hundred or more—“the key to opening up space, and becoming a spacefaring civilization, a multiplanetary species and having the future be incredibly exciting and inspiring.” AS IT RECOVERED from its explosion and moved through 2017, SpaceX screamed ahead, full force, racing through its backlog of seventy missions, worth some $10 billion. With six thousand employees, it at one point flew back-to-back missions within forty-eight hours, as it gobbled up a larger share of the international launch market.

The Moon: A History for the Future

by

Oliver Morton

Published 1 May 2019

Robert Zubrin, an aerospace engineer who in 1998 founded the Mars Society, sees the settlement that the society advocates as a way—perhaps the only way—to regain a cultural vigour he thinks was lost with the closing of the American frontier at the end of the 19th century. Elon Musk, founder of SpaceX and, as I write, probably the world’s most talked-about entrepreneur, sees Mars as a hedge against existential all-eggs-in-the-same-basket disasters. In a messy mix of cosmic compassion and messianic self-belief, Mr Musk is set on making humanity a multiplanetary species, and Mars—eventually, a terraformed Mars—is the first step on that road. Its mixture of mystique, new challenges and science has ensured that whenever the US government sets out long-term space plans, human feet on the sands of Mars are always in the mix. They were there in the Space Exploration Initiative proposed by George H.

…

Something has to happen next, and a ship of artists from around the world is no worse an idea than any other, and better than quite a few. MR MAEZAWA’S TRIP IS TO BE PROVIDED BY ELON MUSK. MR Musk has, in the past, been somewhat sniffy about space tourism. When he founded his company SpaceX in 2003 it was to do real things: to launch satellites, to sell services, to reinvent the human condition by making Homo sapiens a multiplanetary species. Package holidays for plutocrats were not part of the plan. As a provider of practical services to industry and government, SpaceX has succeeded beyond almost all expectation. In the ten years since September 2008, when, at its fourth attempt, SpaceX finally launched its first satellite, the company has gone from triumph to triumph.

…

Tumlinson with Medlicott (2005) brings together many reasons and plans for the Return; helium 3 is discussed in Spudis (1996); Dennis Wingo makes the case for platinum from the Moon in Wingo (2004); the National Academy of Sciences (2007) and the Lunar Exploration Analysis Group (2016) set out the scientific rationale. The idea of America as a second creation is explored in Nye (2003). CHAPTER VI The quotation from the Saturday Review is from Barnouw (1970). For Elon Musk’s achievements and character, see Vance (2015), and for what was the latest version of his infrastructure for a multiplanetary species (but will probably be superseded by the time you read this), see Musk (2018). Robert Zubrin’s Moon proposal is Zubrin (2018). Miller et al (2015) is a fascinating analysis of a public-private Return to the Moon. CHAPTER VII A version of the BOLAS idea is described in Stubbs et al (2018); the charms of Rima Bode are described in Spudis and Richards (2018).

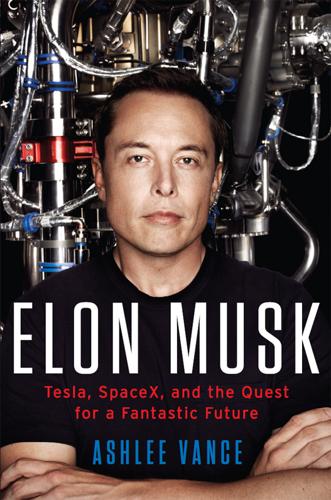

Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic Future

by

Ashlee Vance

Published 18 May 2015

The planet has been heated up and transformed to suit humans. Musk fully intends to try and make this happen. Turning humans into space colonizers is his stated life’s purpose. “I would like to die thinking that humanity has a bright future,” he said. “If we can solve sustainable energy and be well on our way to becoming a multiplanetary species with a self-sustaining civilization on another planet—to cope with a worst-case scenario happening and extinguishing human consciousness—then,” and here he paused for a moment, “I think that would be really good.” If some of the things that Musk says and does sound absurd, that’s because on one level they very much are.

…

Fearing one of his enemies was trying to orchestrate an elaborate setup, Cantrell told Musk to meet him at the Salt Lake City airport, where he would rent a conference room near the Delta lounge. “I wanted him to meet me behind security so he couldn’t pack a gun,” Cantrell said. When the meeting finally took place, Musk and Cantrell hit it off. Musk rolled out his “humans need to become a multiplanetary species” speech, and Cantrell said that if Musk was really serious, he’d be willing to go to Russia—again—and help buy a rocket. In late October 2001, Musk, Cantrell, and Adeo Ressi, Musk’s friend from college, boarded a commercial flight to Moscow. Ressi had been playing the role of Musk’s guardian and trying to ascertain whether his best friend had started to lose his mind.

…

These are people who in childhood exhibit exceptional intellectual depth and max out IQ tests. It’s not uncommon for these children to look out into the world and find flaws—glitches in the system—and construct logical paths in their minds to fix them. For Musk, the call to ensure that mankind is a multiplanetary species partly stems from a life richly influenced by science fiction and technology. Equally it’s a moral imperative that dates back to his childhood. In some form, this has forever been his mandate. Each facet of Musk’s life might be an attempt to soothe a type of existential depression that seems to gnaw at his every fiber.

The Future Is Faster Than You Think: How Converging Technologies Are Transforming Business, Industries, and Our Lives

by

Peter H. Diamandis

and

Steven Kotler

Published 28 Jan 2020

Think how incredible and dynamic that civilization will be.” And even though there’s a heathy rivalry here, Elon Musk doesn’t disagree: “History is going to bifurcate along two directions: One path is we stay on Earth forever, and then there will be some eventual extinction event… the alternative is to become a spacefaring civilization and a multiplanetary species. I think the future is vastly more exciting and interesting if we’re a spacefaring civilization and a multi-planet species, than if we’re not.” Born in Pretoria, South Africa, Musk sold his first computer company at age twelve. After earning a degree from Wharton, then dropping out of Stanford’s PhD program, he repeated his software success with first a $307 million sale of Zip2, next a $1.5 billion sale of PayPal.

…

Finally, with what he considered sufficient resources to make a difference, Musk set out to pursue what he considered the two missions most critical to our survival: breaking our fossil fuel addiction with a thriving solar economy—i.e., his work with Tesla and Solar Cities—and making humanity a multiplanetary species. But unlike Bezos’s lunar launch point for this migration, Musk’s obsession has always been Mars. In 2001, a year before the sale of PayPal, Musk came up with the idea of sending a plant—plant seeds, really—to Mars. In his “Mars Oasis” project, his spaceship would include a sealed chamber with an Earth-like atmosphere, a healthy collection of seeds, and a nutrient gel to speed their growth.

Think Like a Rocket Scientist: Simple Strategies You Can Use to Make Giant Leaps in Work and Life

by

Ozan Varol

Published 13 Apr 2020

“We sleep easy knowing that next year’s software will be better than this year’s,” Musk explains, but “rockets’ [cost] actually gets progressively worse every year.”2 Musk wasn’t the first to spot this trend. But he was among the first to do something about it. He launched SpaceX—short for Space Exploration Technologies—with the audacious goal of colonizing Mars and making humanity a multiplanetary species. But Musk’s deep pockets weren’t enough to buy rockets on the American or the Russian market. He pitched venture capitalists, but they were a hard bunch to convince. “Space is pretty far out of the comfort zone of just about every VC on Earth,” Musk explained. He refused to let his friends invest, because he believed the company had only a 10 percent chance of success.

…

Aerospace consultant Jim Cantrell, recalling their initial encounters, thought Musk was out of his mind.52 When Musk first began thinking about a Mars mission, he called Cantrell out of the blue, introduced himself as an internet billionaire, and told Cantrell about his plans to create a “multiplanetary species.” Musk offered to fly his private jet to Cantrell’s house, but Cantrell said no. “Tell you the truth,” Cantrell recalls, “I wanted to meet him in a place where he couldn’t bring a weapon.” So they met at an airport lounge in Salt Lake City. As wild as Musk’s vision sounded, it was too tantalizing.

Reentry: SpaceX, Elon Musk, and the Reusable Rockets That Launched a Second Space Age

by

Eric Berger

Published 23 Sep 2024

He provided fair compensation and generous stock options to give employees skin in the game. As they succeeded, the private valuation of SpaceX rose and their wealth increased. Some people joined because of this potential for financial reward. Others came because they truly believed in Musk’s messianic mission to settle Mars and make humans a multiplanetary species. Working at SpaceX offered the best chance on Earth to make science fiction dreams a reality, and many employees relished being part of the journey. Still others knew that by putting in a few years at SpaceX they would learn a hell of a lot, earning a PhD from the rocketry equivalent of Harvard University.

…

“We’re confined to one planet until an extinction event,” Musk said. This does not mean abandoning Earth or chewing through its resources. Earth should be protected and preserved, he said. But eventually an asteroid, particularly virulent pandemic, or a nuclear conflict would end our civilization. To avoid this, we must become a multiplanetary species. Mars is far from a paradise. Indeed, it is far less hospitable than the most barren desert or frozen tundra on Earth. But it is the closest, best place to start living off-world. The most striking thing about the speech is that Musk let it all hang out in the wind. He put his entire vision out there, and it felt like this incredibly vulnerable moment.

Elon Musk

by

Walter Isaacson

Published 11 Sep 2023

Cantrell was driving in Utah with the top down on his convertible, “so all I could make out was that some guy named Ian Musk was saying that he was an internet millionaire and needed to talk to me,” he later told Esquire. When Cantrell got home and was able to call him back, Musk explained his vision. “I want to change mankind’s outlook on being a multiplanetary species,” he said. “Can we meet this weekend?” Cantrell had been leading a cloak-and-dagger life because of his dealings with Russian authorities, so he wanted to meet in a safe place without guns. He suggested they meet at the Delta Air Lines club at the Salt Lake City airport. Musk brought Ressi, and they came up with a plan to go to Russia to see if they could buy some launch slots or rockets. 15 Rocket Man SpaceX, 2002 With Adeo Ressi at a rocket facility and a dinner with Russians in Moscow Russia The lunch in the back room of a drab Moscow restaurant consisted of small bites of food interspersed with large shots of vodka.

…

“Dude, why don’t you fucking just give up on one of these two things?” he asked. “If SpaceX speaks to your heart, throw Tesla away.” “No,” Musk said, “that would be another notch in the signpost of ‘Electric cars don’t work,’ and we’d never get to sustainable energy.” Nor could he abandon SpaceX. “We might then never be a multiplanetary species.” The more people pressed him to choose, the more he resisted. “For me emotionally, this was like, you got two kids and you’re running out of food,” he says. “You can give half to each kid, in which case they might both die, or give all the food to one kid and increase the chance that at least one kid survives.

…

“I don’t think from a cognitive standpoint it’s nearly as hard as SpaceX or Tesla,” he said. “It’s not like getting to Mars. It’s not as hard as changing the entire industrial base of Earth to sustainable energy.” Yes, but why? Musk had founded SpaceX, he liked to say, to increase the chances for the survival of human consciousness by making us a multiplanetary species. The grand rationale for Tesla and SolarCity was to lead the way to a sustainable energy future. Optimus and Neuralink were launched to create human-machine interfaces that would protect us from evil artificial intelligence. And Twitter? “At first I thought it didn’t fit into my primary large missions,” he told me in April.

A City on Mars: Can We Settle Space, Should We Settle Space, and Have We Really Thought This Through?

by

Kelly Weinersmith

and

Zach Weinersmith

Published 6 Nov 2023

Surely space settlement presents the best chance since about 50,000 BC to try out something completely new and leave all the bad stuff behind. After five decades of stagnation in human spacefaring, we now have the technology, the capital, and the desire to go beyond the age of quick forays to the Moon and seize our destiny as a multiplanetary species. Well . . . maybe not. If you’re like most of the nonexperts we’ve talked to as we researched this book, you might have some ideas about space settlement that aren’t quite right. We don’t blame you—the public discourse around space settlement is full of myths, fantasies, and outright misunderstanding of basic facts.

…

Although it’s hard to predict the future, it seems to us that if we’re so good at robotics and ecology that we can build a permanent bubble world for 1 million people on a distant oceanless planet, well, surely we can clean some carbon dioxide out of the air on Earth. The other thing is that the attempt at Plan B may be the cause of earthly calamity. There may be good reasons never to build a backup copy—not because we can’t do it, but because having a multiplanetary species may not actually render humanity’s existence more secure. OceanofPDF.com 19. Space Politics by Other Means: On the Possibility of Space War Who controls low-Earth orbit controls near-Earth space. Who controls near-Earth space dominates Terra. Who dominates Terra determines the destiny of humankind.

Moon Rush: The New Space Race

by

Leonard David

Published 6 May 2019

If they had gone to space, how would the world have looked today?” He believes that trips to the Moon can be a part of everyone’s future. “I will be heading to the Moon,” Maezawa says—“just a little earlier than everyone else.” Musk’s “Moon Base Alpha” is part of his master plan for Mars colonization. He envisions us as a multiplanetary species in the not-too-distant future, traveling via a SpaceX fleet labeled the Interplanetary Transport System. “We should have a lunar base by now,” Musk recently said, speaking during a meeting of the International Astronautical Congress in Adelaide, Australia. “What the hell is going on?” He has reiterated his plans to send people to the Moon and Mars and reinforced his commitment to build and fly a fully reusable two-stage rocket capable of heaving 150 metric tons into low Earth orbit, a booster far larger than the Apollo-era Saturn V launcher.

A History of the World in 6 Glasses

by

Tom Standage

Published 1 Jan 2005

This, together with the search for extraterrestrial life (which is also assumed to depend on water), explains why so much effort is being put into locating and understanding the distribution of water on other bodies in the solar system. Some scientists even believe that colonizing Mars is necessary to ensure the continued survival of humanity. Only by becoming a "multiplanetary species," they argue, can we truly guard against the possibility of being wiped out by war, disease, or a mass extinction caused by an asteroid or comet crashing into the Earth. But that will depend on finding supplies of water on other worlds. Water was the first drink to steer the course of human history; now, after ten thousand years, it seems to be back in the driving seat.

The Decadent Society: How We Became the Victims of Our Own Success

by

Ross Douthat

Published 25 Feb 2020

At a certain point, we’ll clear the bottleneck, and it will become clear that our era was a necessary prelude to renewed acceleration—eventually giving us self-driving cars courtesy of a finally profitable Uber, a Mars colony courtesy of the Elon Musk–Jeff Bezos space race, and radical life extension courtesy of Google’s longevity lab or some other zillionaire who can’t imagine shuffling off this mortal coil. All of this could happen on a scale that would be world altering without having the truly utopian scenarios come to pass. Terraforming Mars and becoming a multiplanetary species may be unattainable for now—but just going to Mars would be a bigger leap for mankind than anything we’ve accomplished since Neil Armstrong. The hard problem of consciousness probably isn’t solvable by brain scans and increases in processing power, and so you and I probably won’t actually be uploading our very selves to the cloud—but that doesn’t mean that forms of artificial intelligence can’t radically transform the economy and render many if not most human forms of labor obsolete.

The Capitalist Manifesto

by

Johan Norberg

Published 14 Jun 2023

Ironically, space is only beginning to be conquered now that it is being privatized, with companies such as SpaceX, Blue Origin and Virgin Galactic. They are not going for moonshots but for experimenting, improvising, adjusting and, through incremental improvements, constantly finding new methods and sources of revenue; step by step they are reducing the cost of turning humanity into a multiplanetary species. Each launch of NASA’s Space Launch System, SLS, designed to take us back to the moon, is projected to cost $2 billion. When NASA’s boss suggested in 2019 that it would be quicker and cheaper using SpaceX’s technology instead (projected at $10 million per launch), he got a good lashing by US politicians and had to back down.

Rocket Billionaires: Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, and the New Space Race

by

Tim Fernholz

Published 20 Mar 2018

“The reason I joined the company, one of the key differentiators of our culture, is intense mission focus,” Brian Bjelde, the company’s head of human resources, told me. In August 2003, Bjelde was the seventh employee at the company, and the program manager for the Falcon 1. “Elon founded this company to revolutionize access to space, with the ultimate goal of making humankind a multiplanetary species. There are a lot of people in the industry today that can rally behind that mission . . . and the focus is on Mars.” But the Falcon 1 was not designed to go straight to Mars. It was simply a first step toward the Red Planet. “It was to figure out the basics of rocketry,” Musk told me of the project.

Realizing Tomorrow: The Path to Private Spaceflight

by

Chris Dubbs

,

Emeline Paat-dahlstrom

and

Charles D. Walker

Published 1 Jun 2011

That's kind of silly. My interest in space stems from thinking about what are the important problems facing humanity and life itself. The extension of life to multiple planets seems to be actually the most important thing that we could possibly do." The next big step for mankind is to be a multiplanetary species, and Musk thinks he's got the talent and the money to make it happen in our lifetime. Unlike most visionaries, Musk is more sobered by looking back at the challenges already met, than looking forward at those to come. During the interview, he described the difficult process of rocket development.

Soonish: Ten Emerging Technologies That'll Improve And/or Ruin Everything

by

Kelly Weinersmith

and

Zach Weinersmith

Published 16 Oct 2017

This is what really excites Mr. Faber: “I eventually got bored with racing solar cars, and hang gliding and windsurfing and such, and decided that the biggest benefit I could create for humanity, the most important thing that was going to happen in my lifetime was moving humanity off Earth and becoming a multiplanetary species or an interplanetary species.” We, uh . . . we’re also totally bored with racing and windsurfing, which is why we are sitting in this office editing this document . . . for humanity. SECTION 2 Stuff, Soonish 4. Fusion Power It Powers the Sun, and That’s Nice, but Can It Run My Toaster?

Rocket Dreams: Musk, Bezos and the Trillion-Dollar Space Race

by

Christian Davenport

Published 6 Sep 2025

Since reading science fiction in his childhood, notably Isaac Asimov’s Foundation series, he had been fascinated with space and certain that Mars was key to humanity’s future. With SpaceX, Musk’s goal was reducing the cost of access to space, an endeavor that would help bring about the most significant achievement that humanity could accomplish in his lifetime: becoming a multiplanetary species. In June 2017, I traveled to interview Musk at SpaceX headquarters in Hawthorne, California, just outside of Los Angeles. If there was an aesthetic to the decor there, it could have been called Mars chic. There were images of the Red Planet all over the place. The doormats depicted boot prints in Martian clay, and as I made my way past security into the building, I was greeted by a stark, white wall with a pair of images.

Character Limit: How Elon Musk Destroyed Twitter

by

Kate Conger

and

Ryan Mac

Published 17 Sep 2024

Despite his management failings, he had sold two internet companies and become one of the most successful entrepreneurs of a Web 1.0 era that would see plenty of companies rise to the heavens before exploding into flaming heaps of discarded ideas. Before eBay had even completed its acquisition of PayPal, Musk founded Space Exploration Technologies Corp., or SpaceX, in May 2002. He committed $100 million of his PayPal windfall to space, with the goal of getting to Mars and making humans a multiplanetary species, a particular fixation of his from a childhood immersed in sci-fi novels. Musk wasn’t the only entrepreneur trying to reimagine travel. In 2003, two engineers named Martin Eberhard and Marc Tarpenning founded an electric car start-up called Tesla Motors. Their work caught Musk’s eye and he invested $5.6 million the following year, turning him into Tesla’s largest shareholder and earning him the chairman seat on its board.

On the Edge: The Art of Risking Everything

by

Nate Silver

Published 12 Aug 2024

Billionaires in outer space? They won’t make it either. Yudkowsky referenced a conversation between Elon Musk and Demis Hassabis, the cofounder of Google DeepMind. In Yudkowsky’s stylized version of the dialog, Musk expressed his concern about AI risk by suggesting it was “important to become a multiplanetary species—you know, like set up a Mars colony. And Demis said, ‘They’ll follow you.’ ” Before I unpack how Yudkowsky came to this grim conclusion, I should say that he’d slightly mellowed on his certainty of p(doom) by the time I caught up with him again at the Manifest conference in September 2023.