Unmasking Autism: Discovering the New Faces of Neurodiversity

by

Devon Price

Published 4 Apr 2022

When an Autistic person is not given resources or access to self-knowledge, and when they’re told their stigmatized traits are just signs that they’re a disruptive, overly sensitive, or annoying kid, they have no choice but to develop a neurotypical façade. Maintaining that neurotypical mask feels deeply inauthentic and it’s extremely exhausting to maintain.[5] It’s also not necessarily a conscious choice. Masking is a state of exclusion forced onto us from the outside. A closeted gay person doesn’t just decide one day to be closeted—they’re essentially born into the closet, because heterosexuality is normative, and being gay is treated as a rare afterthought or an aberration. Similarly, Autistic people are born with the mask of neurotypicality pressed against our faces. All people are assumed to think, socialize, feel, express emotion, process sensory information, and communicate in more or less the same ways.

…

Almost anyone can be viewed as defective or abnormal under our current medicalized model of mental illness—at least during particularly trying periods of their lives when they are depressed or their coping breaks down. In this way, neurotypicality is more of an oppressive cultural standard than it actually is a privileged identity a person has. Essentially no one lives up to neurotypical standards all of the time, and the rigidity of those standards harms everyone.[42] Much as heteronormativity harms straight and queer folks alike, neurotypicality hurts people no matter their mental health status. Autism is just one source of neurodiversity in our world. The term neurodiverse refers to the wide spectrum of individuals whose thoughts, emotions, or behaviors have been stigmatized as unhealthy, abnormal, or dangerous.

…

Though masking is incredibly taxing and causes us a lot of existential turmoil, it’s rewarded and facilitated by neurotypical people. Masking makes Autistic people easier to “deal” with. It renders us compliant and quiet. It also traps us. Once you’ve proven yourself capable of suffering in silence, neurotypical people tend to expect you’ll be able to do it forever, no matter the cost. Being a well-behaved Autistic person puts us in a real double bind and forces many of us to keep masking for far longer (and far more pervasively) than we want to. The Double Bind of Being “Well-Behaved” Psychiatrists and psychologists have always defined Autism by how the disability impacts neurotypical people.

Secrets of the Autistic Millionaire: Everything I Know Now About Autism and Asperger's That I Wish I'd Known Then

by

David William Plummer

Published 14 Sep 2021

But the reaction is neither intentional nor elective––they just cannot ignore it. It is key to remember that the person with autism does not experience the stimulus in the same way that a neurotypical person would. Take the example of the scratchy tag in the neck of a new shirt. When a person with autism puts on such a shirt, it is little different from a neurotypical person doing the same. In the case of the neurotypical person, however, their brain quickly recognizes the sensation as unimportant and relegates it to the back of the mind, eventually going unnoticed. For 125 the person with autism, however, the brain does not seem to have the ability to selectively ignore certain stimuli.

…

In people with autism, this mirror neuron system is markedly different and does not function as it does in neurotypical people: those with autism must mechanically process what the other person is feeling, with only past experience being the basis of predictions for how their words and reactions will be met. There may be little to none of the internal intuition that the neurotypical seem to have from birth. In summary, to the individual with autism, it sometimes feels as though the neurotypical individuals have a sixth sense, an almost magical way of automatically intuiting what other people are feeling deep inside.

…

Being the “Other” Parent Before we examine the challenges in being a parent with autism, we should acknowledge the unique challenges of being the neurotypical parent in a mixed marriage with kids. There is simply a certain set of things that the partner with autism may not be good at –– let’s say something as simple as phoning to schedule appointments for the baby 203 with the pediatrician’s office. If the partner with autism isn’t comfortable on the phone, the neurotypical partner may wind up picking up that role by default. This only works, of course, if the partner with autism picks up other responsibilities and roles in the parenting arena that, in turn, compensate for or take work off the shoulders of the neurotypical parent.

I Am Autistic: a Workbook: Sensory Tools, Practical Advice, and Interactive Journaling for Understanding Life with Autism (By Someone Diagnosed With it): Sensory Tools, Practical Advice, and Interactive Journaling for Understanding Life with Autism (By Someone Diagnosed With it)

by

Chanelle Moriah

Published 25 Oct 2022

“Person with cancer,” “person with dementia,” “person with the flu.” Autism is not an illness. It’s not something that’s wrong with me. It’s a different neurotype. By saying that a person should use only PFL, you’re also saying that if you can’t identify with the neurotypical neurotype then you shouldn’t identify with a neurotype at all. Now, I know most people don’t say that they are neurotypical—heck, most of them don’t even know the word. But I can guarantee that if they did, they wouldn’t be told to say “person with a neurotypical neurotype.” I am autistic, and I love that about me. “Functioning” labels When I say “functioning” labels, I am referring to the terms “high-functioning” and “low-functioning.”

…

Honestly, though, in many contexts neither party will notice that there was a miscommunication, unless it comes up again later. Implying Implying something means to use unspoken language and assume that the listener understands. Many autistics will particularly struggle with implications, because our brains do not function or think in the same way as those of neurotypicals. Neurotypicals pick up on implications more easily because their brains function similarly to other neurotypicals. In the same way that autistics might not pick up on implications, we might not use them either. When I say: When you say: “Your music is loud.” I am simply stating a fact. I’m not necessarily complaining or asking you to turn it down.

…

This can sometimes lead to a lack of understanding between people who are motivated in different ways. Completing tasks: neurodivergent vs. neurotypical Here is a concept many autistics might relate to, which is potentially explained by the information on the previous two topics. Often, things that an autistic might be able to do inexplicably quickly, a neurotypical person may take much longer to complete. On the other hand, things that a neurotypical might be able to do quickly and efficiently may take an autistic person a lot longer. For example, I can finish any assignment to a high standard in a matter of hours, but getting the dishes done can take me up to half a day.

Living Well on the Spectrum

by

Valerie L. Gaus

Published 4 Feb 2011

It is, however, just as important not to overstate these differences. Focusing only on how you differ from neurotypical people is what leads to the feeling of being a member of another species expressed by some people on the spectrum, as mentioned in Chapter 1. Remember that you have many human characteristics in common with neurotypical people. For one thing, neurotypicals do not live completely without 39 40 LIFE ON THE SPECTRUM stress, and life for people on the spectrum is more than unremitting stress. I’ll remind you where common ground exists between you and neurotypical people throughout the next few chapters. Also keep in mind that no two people are alike and no one person with an ASD has all of the characteristics that I will discuss in these chapters.

…

Human Social Cognition As with the cognitive differences discussed in Chapter 2, ASDs involve social differences that can affect you in many ways, in all of the arenas of your life. To understand the social ramifications of having an ASD, it will help to know how neurotypical people operate successfully in social situations. How do neurotypical people understand other people? How do they seem to know what to say and do, even in brand-new situations? If you’re on the spectrum, you may very well have pondered these questions as you observed your neurotypical family members and friends navigating the social world with apparent ease. But these questions have also been asked for decades in an area of scientific psychology called social cognition.

…

Granted, I have had people with AS and HFA tell me that they feel as though they function so differently from others that they might as well be considered a separate species. It is true that brains of people on the spectrum function in unique ways that often make them stand out from neurotypical people, and I will be giving you many examples of that in this book. But we in the autism community, professionals and affected people alike, can sometimes get so caught up in defining these differences that we lose sight of the fact that every person on the spectrum is bound to every neurotypical person by one thing, and that is a common membership in the same species. Your unique brain is still a human brain. For that reason, the science of positive psychology and human strengths has everything to do with you.

We're Not Broken: Changing the Autism Conversation

by

Eric Garcia

Published 2 Aug 2021

In countless news reports, increased productivity is one of the features employers highlighted when talking about hiring autistic people. But Cunningham worries that this could backfire. “When people say that their autistic employees are a hundred and seventy percent more productive than their neurotypical counterparts, now that’s a huge problem,” she said. If autistic people are only slightly more productive, employers feel cheated for getting someone who is only, say, a hundred and forty percent more productive. The productivity myth can also make neurotypical employees resentful of autistic employees. There is also concern that these types of programs are focused on hiring autistic people into STEM fields only. Julia Bascom, the executive director of the Autistic Self Advocacy Network, said while certain companies do a good job and promote autistic people in management, there is a risk of just focusing on a certain type of autistic employee.

…

“We’re focused on helping employers to see that there are better ways of assessing people’s talents and competencies,” than just glad-handing and job interviews, which Kriss said has been shown to be a poor method for recruiting for neurotypicals too. “And just good management is going to get a lot of people success, [it’s] going to help a lot of people be more successful,” regardless of their neurotype. He also added that the company is moving beyond technology and financial services and hopes to work with the “intellectually challenged” but that there will be some hurdles because those aren’t the markets where Specialisterne started.

…

A survey of forty-three parents and their autistic sons in Belgium and the Netherlands in the Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders found that half of the parents surveyed said they did not know that their children had masturbated or experienced an orgasm. Conversely, very few parents overestimated their neurotypical sons’ experiences. Gravino emphasized that one problem with teaching consent is that autistic people are often infantilized, so they typically don’t receive proper sex education. “So, when you’re always seeing someone as a child, you’re thinking that they’re innocent; you’re not seeing them as a fully realized adult with the same desires and needs as other neurotypical adults,” she said. “And so parents will say, ‘Well, no, if I tell my child about sex, they’re going to be thinking about sex and want to have sex.’

Loving Someone With Asperger's Syndrome: Understanding and Connecting With Your Partner

by

Cindy Ariel

Published 1 Mar 2012

It seems to ignore problems suffered by AS partners, who try hard to please the sometimes seemingly irrational (neurotypical) partner. Some partners with AS lament that they work hard to please their partners, but cannot change the core of their personalities. They then feel bad when they do not or cannot meet the neurotypical standard. The ultimate failure of relationships can lead many partners with AS to shut down and choose not to relate at all. This can also lead from frustration to anger and depression. Feeling Alone Mental health professionals understand that relationship problems between someone with AS and a neurotypical partner stem from issues on both sides.

…

These qualities, along with other AS advantages, provide a strong foundation for emotion-based attraction. But the main way that neurotypical partners seem to think about falling in love has to do with the way a love interest makes them feel and how they feel about her. Tony Attwood, a psychologist practicing in Australia who is well known for his work in the field of autism and Asperger’s syndrome, observes that partners of people on the autism spectrum often fall on the opposite end of the empathy continuum from their autistic partners. Attwood refers to the neurotypical partners as “intuitive experts” because they show a very good understanding of, and empathy toward, the perspectives of others (Attwood 2007b).

…

Building Bridges In one of the offices at our practice, a poster hangs with a picture of a bridge and a caption that reads, “Communication: Let’s build bridges, not walls.” Invariably, people with Asperger’s make cynical comments, such as, “How neurotypical.” A recent article in Psychology Today (Helgoe 2010) debunks the myth that most people are outgoing and sociable. But being sociable and extroverted is usually considered better than being shy or introverted. The way neurotypical people often like to build bridges of communication starts with eye contact and social chitchat, which don’t come naturally to people with AS. While social skills are important, we can relate to others using varying amounts of eye contact or chitchat.

How to Be Human: An Autistic Man's Guide to Life

by

Jory Fleming

Published 19 Apr 2021

Even if two people who are very well-intentioned try to explain it to each other, there will be some things where both of us will shake our heads or shrug our shoulders and be like, I can’t get there.” Rather, Jory’s story is a window into what it is like to live in a world constructed for neurotypical brains when your mind is not. It is the story of what it is like to begin each day knowing that you are fundamentally different from every other person pouring coffee or tea into their mug. It is a memoir of life inside a gifted and disparate mind. As Jory shares his insights into thinking and navigating in a neurotypical world, it may lead you to question basic assumptions about how all of our minds work. * * * The first few times I spoke with Jory, my brain hurt.

…

Sometimes, I read the online exchanges and I wonder who truly struggles with communication here. 7 Personality Is a Choice Talking about Personality: A key component in how Jory interacts with the world is through personality. But he views personality in a very different way from most neurotypical people. Most people tend to view personality as something innate, which we are largely born with. Jory, however, views personality as a choice. He describes it as a feature that he has worked to construct internally, in order to relate better to the neurotypical people around him. His personality of choice may surprise you. He has chosen Ruthless Optimism. JORY: For most people, their environment and culture shape the components of their identity in some ways.

…

I can mess with pens or the leash or some other small object, because that is more acceptable. I still may sing a nonsense song in the grocery store, but I try to turn down the volume. I know that neurotypical people sometimes engage in some of these behaviors too. They may mess with their hair or bite their fingernails or chew on their lips or hold up their hands, but it seems that they are able to modify that behavior or dial it back a lot more smoothly than people with autism. It’s a bit like a musical composition, where different notes go together. When neurotypical people do these things, there’s something about it that doesn’t seem discordant or off, it blends. But when an autistic person engages in these behaviors, it has a different sound.

Odd Girl Out: An Autistic Woman in a Neurotypical World

by

Laura James

Published 5 Apr 2017

I might not strive for huge personal happiness, but is it wrong that I don’t try, even if it is just for Tim? Sarah Wild believes autistic happiness is different. She says: ‘We neurotypical people have to stop projecting what our concepts of happiness are onto the autistic population because autistic happiness is not the same. ‘Neurotypical professionals have ideas about living independently, having a job, being economically viable, having friends. But they’re all neurotypical indexes of happiness and no one has bothered to ask autistic people what makes them happy, what are the things they need to be able to function. That’s the next thing that needs to come.

…

I may not have been able to get my hair to flick in the way she did, but I could adopt her inscrutable expression, and power through the pain. Copying neurotypical behaviour is an exceptionally strong coping mechanism in most autistic girls. Unlike boys with autism, who are often happy to strike out on their own and just be themselves, girls tend to have a strong need to fit in. Mimicking the behaviour, style of speech, interests and social interactions of others provides something akin to a blueprint for life. While neurotypical girls have an innate understanding of how to behave, autistic girls tend to have to learn these behaviours by studying how others do them.

…

When I talk to adults with Asperger’s in groups – sometimes several hundred – I will say, OK, guys, what are your biggest challenges? Most of them say managing anxiety and they say it affects their quality of life far more than any other ASD feature. ‘One [neurotypical] approach is to say to the person with Asperger’s that they should just relax. The person with Asperger’s says, I don’t know how to relax. Neurotypicals just switch on relax. The person with Asperger’s can’t find the switch. It’s like trying to fall asleep – the more you try to fall asleep, the more elusive it is.’ Dr Somayya Kajee, the psychiatrist who diagnosed me at the Anchor Psychiatry Group in Norwich, agrees that anxiety may be a factor of autism for many.

Autistic Community and the Neurodiversity Movement: Stories From the Frontline

by

Steven K. Kapp

Published 19 Nov 2019

The notion that we lack empathy was quickly deconstructed as it became clear that neurologically typical (NT) people had considerably less empathy with us than we had with them. A lot of lifelong pain was shared and empathized with. As part of processing those experiences, we started developing our own theories of neurotypicality—of why these strange people, who form the majority, do what they do. We had a bit of fun with it; tongue-in-cheek terms like “neurotypical syndrome” and “social dependency disorder” were thrown around. Some of us also felt inspired to explain ourselves to the neurotypical population using our newly found collective insight [6]. As we were so used to being misunderstood, patronized, and pathologized, it was a relief to have the shoe on the other foot.

…

Neurodiversity has come to mean “variation in neurocognitive functioning” (p. 3) [1], a broad concept that includes everyone: both neurodivergent people (those with a condition that renders their neurocognitive functioning significantly different from a “normal” range) and neurotypical people (those within that socially acceptable range). The neurodiversity movement advocates for the rights of neurodivergent people, applying a framework or approach that values the full spectra of differences and rights such as inclusion and autonomy. The movement arguably adopts a spectrum or dimensional concept to neurodiversity, in which people’s neurocognitive differences largely have no natural boundaries. While the extension from this concept to group-based identity politics that distinguish between the neurodivergent and neurotypical may at first seem contradictory, the neurodiversity framework draws from reactions to existing stigma- and mistreatment-inducing medical categories imposed on people that they 1 Introduction 3 reclaim by negotiating their meaning into an affirmative construct.

…

While the extension from this concept to group-based identity politics that distinguish between the neurodivergent and neurotypical may at first seem contradictory, the neurodiversity framework draws from reactions to existing stigma- and mistreatment-inducing medical categories imposed on people that they 1 Introduction 3 reclaim by negotiating their meaning into an affirmative construct. People who are not discriminated against on the basis of their perceived or actual neurodivergences arguably benefit from neurotypical privilege [2], so they do not need corresponding legal protections and access to services. I have observed little serious aggrandizement of neurodivergent people or denigration of neurotypical people, but satire has been misinterpreted (Tisoncik, Chapter 5) or rhetoric misunderstood due to disability-related communication or class differences. The Diversity in Neurodiversity Although the people for whom the neurodiversity movement advocates far exceed autistic people, they also fall outside the main scope of the book.

Spectrum Women: Walking to the Beat of Autism

by

Barb Cook

and

Samantha Craft

Published 20 Aug 2018

In my clinical experience I have found spectrum girls and women have the smartest coping mechanisms for their social communication difficulties. These mechanisms include using observation, research, and imitation to be able to emulate neurotypical social communication. A helpful analogy is learning a new language. If one moves to Japan where most people speak Japanese, but one insists on speaking English, there are going to be communication problems. To navigate a largely neurotypical community, it makes sense to learn the communication system of that community. It is effortful to do so. Girls and women become exhausted by the intellectual effort, not only of learning the system, but the need to use it on a daily basis.

…

Sometimes, my mind gets overwhelmed with so much information that I cannot function. This is the perpetual conundrum with being autistic and having issues with executive functioning and task inertia. Agony Autie (2017) put it brilliantly: You gotta remember I believed I was neurotypical all my life; I believed I was a failing neurotypical. All my life, I remember thinking, “Why can’t I do this? Why can’t I keep this together?” … You feel like it makes sense, but at the same time, you then have to reimagine your whole life again. I couldn’t have put it better myself. I was academically able, behaved myself, and permanently masked and camouflaged myself so I wasn’t seen as “the weird kid” when I had difficulties starting on a project, assignment, or research paper.

…

I could see clear signs of frustration in my managers’ faces when they said, “We know you can do this.” I know I can do it too! However, just because I can’t on one day doesn’t mean I’m completely incapable. Some days are better than others, and this rings true for all of us—neurodiverse and neurotypical alike. Because I’ve “worn the neurotypical mask” for so long and only since my diagnosis have I acquired the vocabulary to be able to explain why I’m having difficulties. I feel as if these are being interpreted as excuses rather than reasons, which makes me feel that I’m being gaslighted: you’re not autistic, you’re just lazy.

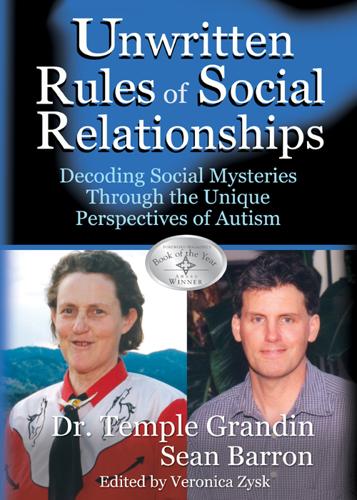

The Unwritten Rules of Social Relationships: Decoding Social Mysteries Through the Unique Perspectives of Autism

by

Temple Grandin

and

Sean Barron

Published 30 Sep 2012

We offer this book in the hope that people of both cultures—those with autism and neurotypicals alike—can gain a deeper awareness of and appreciation for the other. To do that, we can think of no better way than sharing with you how we think about social relationships—this is how we each gain perspective of the other. We could enumerate any number of unwritten social rules, offer hundreds of bulleted examples of social behaviors we had learned in a neat and organized manner, but they would have little lasting impression on neurotypical (NT) people until they first understood what it’s like to be “in our heads,” to hear the conversations we have with ourselves about the people and the situations we experience.

…

Isn’t that interesting? You know there’s got to be many AS students in that school. But the conclusion I’m drawing is that more than just AS students need social skills training—the neurotypical “techie” students do too. Interestingly, there is a link between autism and engineering. Research by Simon Baron-Cohen indicated that there were 2.5 times as many engineers in the family history of people with autism as in their neurotypical counterparts. It makes sense: the really social people are less likely to be interested in building bridges or designing power plants. Today, teaching manners and etiquette just isn’t the priority it used to be when I was growing up.

…

I still saw only the surface of social situations and drew conclusions that reflected absolutes rather than acknowledging the emotional complexities inherent in social relationships. Emotions are the back-seat drivers of how neurotypical people act in public settings. Even when boundaries of public versus private behaviors are clear, emotions can throw all of that logical thought into the wind. This is far more frequent with neurotypicals than it is for the rule-bound person with autism. However, we mention it to shed light on the difficulty it makes for people with ASD to learn public versus private words and actions. Temple explains: My father was a highly unpredictable man when it came to his emotions.

Nerdy, Shy, and Socially Inappropriate

by

Cynthia Kim

Published 20 Sep 2014

For years, Sang was certain he was communicating clearly with me but most of what he was saying wasn’t truly getting through. Often, neurotypical people communicate in subtle ways that autistic people find difficult to interpret. In particular, body language, facial expressions, and implied communication can be hard for people on the spectrum to interpret correctly. For example, I had no idea until recently that when someone walks into the kitchen and says, “Oh, those cookies smell delicious” they’re hinting that they would like me to offer them a cookie. My usual response of “thank you” followed by continuing to clean up the kitchen or change the subject is seen by most neurotypical people as cold and rude.

…

Even without understanding all of my autistic traits and what they meant to our relationship, we managed to develop quite a few accommodations over the years. Growing up in a household with an Aspie parent is going to be different, whether the parent has a diagnosis or not. For a neurotypical kid like Jess, it was probably confusing at times. In a way, she grew up in a bicultural household, and like many children from multicultural families, she learned to intuitively translate between autistic and neurotypical. There’s some question about how having a parent with Asperger’s affects a typical child. I definitely see ways in which my Aspie traits have influenced Jess’s behavior. She’s told me stories about how friends at college or colleagues at work have pointed out deficiencies in her social skills.

…

and communication see body language and non-verbal communication; social/communication skills and deficits and competencies 216–17 coping strategies see coping strategies/mechanisms diagnosis see diagnosis of Asperger’s Syndrome/ASD and emotion see emotions and empathy see empathy and executive function deficit see executive function (EF) and face blindness 43 gender differences 20, 3–21, 24 growing older on the spectrum 133–7 and insomnia 128–33 Kanner’s definition of autism 21 labeling see labeling motor development delay 118 and perfectionism 191–3 and perimenopause symptoms 134–5 and sensory sensitivities see sensory sensitivities strengths associated with 210–15 and thinking see thinking traits making autistic individuals vulnerable to bullying 29 and triggers 66–7 Baumeister, Roy 179 bliss 145 blogging 19–18, 230, 231 blunted affect 37–9 body, autistic 117–37 the autistic brain 69, 74, 141, 146, 9–168, 171 see also executive function (EF) and clumsiness 117–18 and growing older on the spectrum 133–7 and insomnia 128–33 and sensation see sensory seeking; sensory sensitivities; stimming and sports/exercise 57, 106, 119–28 body language and non-verbal communication 6–35, 46–37, 51 blunted affect 37–9 eye contact 39, 42–40, 44–5 facial expression see facial expression intentional employment of 39–41 non-verbal cues 39, 6–45, 51, 64, 65, 223 brains 69, 74, 107, 141, 146, 171 brain–body communication 168–9 executive function see executive function (EF) and inhibition 165 bullying 9–25, 223 calmness 214 catastrophizing 193–7 change, resistance to 86, 2–91, 166 checklists 178 chunking 177 clumsiness 117–18 cognitive empathy 81, 96, 154–7 cognitive flexibility 162, 166 communication see body language and non-verbal communication; language; social/communication skills and deficits compassion 231–2 competencies 216–17 compromise 66 confrontation skills deficit 41–140, 148 contentment 144–5 control 182–5 meltdowns and loss of see meltdowns coping strategies/mechanisms 29, 32, 9–86, 135, 189, 214, 218 and control 183–5 with executive function deficit 172–3 pattern recognition see pattern recognition rescue strategies for new parents 76–7 routines as 86, 94–89, 166 rules as 36, 86, 87–9 for sensory sensitivities 109–16 special interests 96–101 strengths as coping mechanisms 210–12 curiosity 211 decision making 158–61 dependability 214–15 depression 127 detachment 80, 198, 214 see also withdrawal/shutdown determination 141, 215 developmental disability 31–4 diagnosis of Asperger’s Syndrome/ASD and acceptance 228–32 and being understood 61–60, 71 and DSM-5 21 gender differences with diagnosis rates 2–21, 23 growing up undiagnosed 18–13, 34–20, 6–53, 59, 86, 147, 182, 192–3 and labeling see labeling late diagnosis 14, 21 resistance to change as a criterion for 91–2 and self-redefinition 208–27 self-understanding growing from 6–35, 61–60, 72, 182, 10–208, 225, 229–32 sharing your diagnosis with your child 82 Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) 21 disability, developmental 4–31, 209–10 discipline 214–15 domestic violence 223 driving 77 ego depletion 179–80 elation 144, 145 emotions 138–57 alexithymia 141–4 anger constellation 146–9 catastrophizing as an emotional magnet 196 discriminating the target of others’ expressions of 140–41 emotional detachment 80, 198, 214 and empathy see empathy expressing love and feelings 68, 69, 72, 74, 138 feeling overwhelmed by others’ emotions 141, 156 getting in touch with feelings 144–52 happiness constellation 144–6 identifying 9–138, 140, 141–3 meltdowns see meltdowns modulating the strength of 40–139, 141 sadness constellation 149–52 and sensations 142, 6–145, 149, 170 see also anxiety; panic; shame empathy 152–7 cognitive (perspective taking) 81, 96, 7–154, 210, 231 meaning of a lack of 157 Sally–Anne test 155 vs. sympathy 153–4 executive function (EF) 158–81 acting on a problem 168–73 and the anger constellation 146–7 attention 162, 164–5 conservation of EF, and ego depletion 179–81 decision making 158–61 inhibition 165, 178 initiating actions 165 monitoring actions 165–6 planning 93, 161, 163 problem solving see problem solving procrastination and EF fail 173–8 and stimming 180–81 and time agnosia 178–9 verbal reasoning 164 exercise see sports and exercise face blindness (prosopagnosia) 43 facial expression 36 blunted affect 37–9 eye contact 39, 42–40, 44–5 faking 39 frowning 16, 38 reading 42–4 family responsibilities household see household management parenting see parenting fear 18, 26, 27, 105, 110, 204, 231 of abandonment 151 and catastrophizing 196 irrationality of 221, 223 of not being good enough 147 see also anxiety feeling see emotions; sensory sensitivities fight or flight response 45 food sensitivities 13–112, 115 Frost Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale 192 frowning 16, 38 frustration 146 functioning labels 215–18 see also labeling games 23–4 gender differences with ASD in diagnosis 20, 21–3 in play 24 generalizing 63, 210, 212 giftedness 30–33 grief 150–51 guilt 75 handholding 64 happiness 144–6 headbanging 75, 103, 106, 202, 203, 205 honesty 210–11 household management 61–2 and parenting 73–4 humiliation 147 hypersensitivity see sensory sensitivities hyposensitivity 170–73 indignation 147–8 infodumping 95–6 inhibition 165, 178 insomnia 128–33 intelligence 21, 2–31, 33, 51–50, 71 interests relationships and common interests 56–7 special 77, 96–101 interoceptive feedback 170 irritability 147 joy 145 joys of parenting a toddler 77–9 Kanner, Leo 21 Kim, Jess 2–71, 75, 8–77, 79–85 Kim, Sang Hwan 56, 57, 58, 62–59, 64, 6–65, 67, 70–68, 71, 75, 3–82, 85, 92, 6–135, 41–140, 148, 183, 188, 189, 200, 224 labeling 32–30, 208–27 finding the right labels 209–15 functioning labels in practice 215–18 and self-redefinition 208–27 and the wish for normality 225–6 language body language see body language and non-verbal communication glitches 135–6 literal interpretation 27, 67–8 social use of (pragmatics) 45–52 verbal cues 49, 67 verbal processing 47–51 light sensitivities 110–11 Linden, Fabian 227 literal interpretation 27, 67–8 love compassion 231–2 expressing love 68, 69, 72, 74 and parenting 72, 74 and sex see sex life loyalty 211 marriage 70–59, 75, 188–9 see also parenting; sex life martial arts 57, 106, 121–7 melatonin 132–3 meltdowns 54, 60, 67, 75, 110, 116, 124, 171, 200–207 anatomy of a meltdown 201–5 helping someone through a meltdown 207 nightmares as forms of meltdown 148 triggers 205–6 see also headbanging memory problems 136–7 working memory 164 see also reminders menopause/perimenopause 133, 134–5 metaphors 27 mindfulness 176 mindful physical activity 127 missing word problem 135–6 monologuing 95 motor coordination 18–117, 134 motor development delay 118 music 76 neurotypical people/behaviour acting on a problem 168 Aspie parenting of see parenting emotional interaction 140 expressing love 68, 69, 70 filtering sensory data 170–71 marriage to an Aspie partner 70–59, 75, 188 the neurotypical brain 69 and special interests 99 subtle communication ways 67 nightmares 148 NO reflex 92–4 non-verbal communication see body language and non-verbal communication nonjudgmentalism 210 optimism 211–12 panic 159, 185, 204 and the NO reflex 93, 94 see also meltdowns parenting 54, 71–85 and the child’s venture into the world 79–82 expressing love 72, 74 infancy and motherhood 74–7 joys of parenting a toddler 77–9 rescue strategies for new parents 76–7 and retreat 75, 83 routines 78 sharing your ASD diagnosis with your child 82 support 75, 82–3 teenagers and the approach to adulthood 82–5 unconventional 72–4 pattern recognition 27, 33, 34, 36, 86, 87, 88, 214 peace 145 peer pressure 81 perfectionism 26, 189–93 perimenopause 133, 134–5 perseveration 95–6 perspective taking 81, 96, 7–154, 210, 231 Sally–Anne test 155 see also empathy pets 76 phones, communication problems with 48–9 physical activity see sports and exercise planning 93, 161, 163 aids 178 strategies 176–7 play 4–23, 31 and parenting 78–9 pragmatics 46–52 prioritizing 172, 177 problem solving 4–163, 210, 211 acting on a problem 168–73 and executive function impairment 175–8 procrastinating in 173–5 procrastination 173–5 prosopagnosia (face blindness) 43 rage 148 relationships 53–70 alexithymia and 142–3 apologizing 62 balancing adaptation and acceptance 69–70 and common interests 56–7 and compromise 66 and empathy see empathy expressing love 68, 69, 72, 74 see also sex life intimate 4–63, 114–15 see also sex life making friends 7–56, 79–80 marriage 70–59, 75, 188–9 see also sex life and the need for withdrawal 65–6 not being understood 59–60 parent–child see parenting shrinking–growing cycle 56–9 spontaneous affection 64 unintentional hurtfulness 60–59, 62–3 reminders 74, 167, 177, 180 software/apps 176–7 resentment 148 resistance to change 86, 2–91, 166 and the NO reflex 92–4 rigidity 86–96 rigid thinking 7–146, 166 see also perseveration; resistance to change; routines; rules rocking chairs 76 Rogers, K., Dziobek, I. et al. 156–7 routines appropriateness of 91 as coping strategies 86, 94–89, 166 and the NO reflex 92–4 and parenting 74, 78 and problem solving 176 and resistance to change 86, 2–91, 166 and spontaneity 91, 92 rules as coping strategies 36, 86, 87–9 learning social rules 27, 33–4 and spontaneity 89 sadness 149–52 Sally–Anne test 155 self-care 187–8 self-control 182–5 sensory filtering 170–71 sensory regulation/stimming 4–102, 9–108, 81–180, 230 sensory seeking 9–104, 124, 126 sensory sensitivities 63, 109–16 and the anger constellation 146–7 emotions and sensations 142, 6–145, 149, 170 hyposensitivity 170–73 impact on intimacy 63, 114–15 interoceptive feedback 170 to light 110–11 and parenting 73, 74 sensory overload 63, 74, 110, 116, 127 to smell 112–13 to sound 111–12 to taste 112–13 to touch 63, 64, 113–15 sex life and “bliss” 145 and sensory sensitivities 63, 114–15 sexual abuse 223 shame 75, 147, 182, 183, 185–9 shutdown see withdrawal/shutdown shyness 14, 23, 27 sincerity 211 singing 76 sleep problems 128–33 nightmares 148 smell sensitivities 112–13 social/communication skills and deficits 35–52 and aphasia 135–6 apologizing 62 blunted affect 37–9 body language see body language and non-verbal communication; facial expression of a child with an Aspie parent 84–5 compensating for a partner’s deficits 65, 75, 85 confrontation skills deficit 41–140, 148 coping strategies in social interaction see coping strategies/mechanisms eye contact 39, 42–40, 44–5 generalizing 63, 210, 212 learning social rules 27, 33–4 need for explicit communication 67–8 neurotypical subtlety in communication 67 non-verbal communication see body language and non-verbal communication; facial expression not being understood 59–60 and parenting 73 perseverance with communication 67–8 pragmatic impairments 46–52 and relationships see relationships scaring others 36–41 and social anxiety 220–25 social use of language 45–52 telephone communication problems 48–9 unintentional hurtfulness 60–59, 62–3 verbal cues 49, 67 verbal reasoning 164 see also language social power balance 45 social scripts 86, 88, 167, 180 sound sensitivities 111–12 special interests 77, 96–101 spontaneity and rules/routines 89, 91, 92 spontaneous affection 64 sports and exercise 57, 106, 28–119, 134 mindful physical activity 127 and sensory seeking 124, 126 and sleep 130 stimming 4–102, 9–108, 81–180, 230 stress response fight or flight 45 triggers 66–7 sympathy 153–4 tactile sensitivities/defensiveness 63, 64, 113–15 taste sensitivities 112–13 telephone communication problems 48–9 thinking in absolutes 193–7 catastrophizing 193–7 flexible 162, 166 generalizing 63, 210, 212 perspective taking 81, 96, 7–154, 210, 231 rigid 7–146, 166 verbal reasoning 164 time agnosia 178–9 touch 63, 64 tactile sensitivities/defensiveness 63, 64, 113–15 triggers of meltdown 205–6 of smell and taste sensitivities 112 of stress response 66–7 of withdrawal 199 values 211 verbal processing 47–51 verbal reasoning 164 walking 77 water 76 Willey, Liane Holliday 64 withdrawal/shutdown 60, 67, 110, 116, 197–200 common signs of 198 helping someone through 207 need for withdrawal in a relationship 65–6 parenting and retreat 75, 83 and resurfacing 200 wonder 145 working memory 164 Zen 208 Also available Pretending to be Normal Living with Asperger’s Syndrome (Autism Spectrum Disorder) Liane Holliday Willey Foreword by Tony Attwood ISBN 978 1 84905 755 4 eISBN 978 1 84642 498 4 Compelling and witty, Liane Holliday Willey’s account of growing to adulthood as an undiagnosed ‘Aspie’ has been read by thousands of people on and off the autism spectrum since it was first published in 1999.

The Autistic Brain: Thinking Across the Spectrum

by

Temple Grandin

and

Richard Panek

Published 15 Feb 2013

A 2011 fMRI study in the Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders found that the brains in a sample of high-functioning autistics and typically developing individuals seemed to respond to eye contact in opposite fashions. In the neurotypical brain, the right temporoparietal junction (TPJ) was active to direct gaze, while in the autistic subject, the TPJ was active to averted gaze. Researchers think that the TPJ is associated with social tasks that include judgments of others’ mental states. The study found the opposite pattern in the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex: in neurotypicals, activation to averted gaze; in autistics, activation to direct gaze. So it’s not that autistics don’t respond to eye contact, it’s that their response is the opposite of neurotypicals’. “Sensitivity to gaze in dlPFC demonstrates that direct gaze does elicit a specific neural response in participants with autism,” the study said.

…

The problem, however, is “that this response may be similar to processing of averted gaze in typically developing participants.” What a neurotypical person feels when someone won’t make eye contact might be what a person with autism feels when someone does make eye contact. And vice versa: What a neurotypical feels when someone does make eye contact might be what an autistic feels when someone doesn’t make eye contact. For a person with autism who is trying to navigate a social situation, welcoming cues from a neurotypical might be interpreted as aversive cues. Up is down, and down is up. Overconnectivity and underconnectivity.

…

On a computer screen, biological motion is nothing more than dots moving, but the dots are arrayed in such a way that they suggest an action a living person or animal would perform, like running. Studies have repeatedly shown that people with autism can identify biological motion, but they don’t do so with the same ease as neurotypicals. Nor do they attach emotions and feelings to the motions. What’s more, they use different parts of the brain than neurotypicals do. Neurotypicals show a lot of activation in both hemispheres, while autistics show less activation overall. The way the autistic brain engages with biological motion is reminiscent of Tito’s description of focusing on a door at the expense of seeing the room, or a description by Donna Williams I once read, of her being entranced by individual motes of dust.

Against Technoableism: Rethinking Who Needs Improvement

by

Ashley Shew

Published 18 Sep 2023

As professor Nick Walker has described it, the idea that “there is one ‘normal’ or ‘healthy’ type of brain or mind, or one ‘right’ style of neurocognitive functioning, is a culturally constructed fiction, no more valid (and no more conducive to a healthy society or to the overall well-being of humanity) than the idea that there is one ‘normal’ or ‘right’ ethnicity, gender, or culture.”19 Its sibling term, neurodivergent, was coined by Kassianne Asasumasu in the 1990s to describe a wide variety of diagnoses/brains/neurotypes, not only autistic ones; it is a more capacious category, intended to take a wider view on difference. The label neurodivergent includes psychiatric diagnoses, learning disabilities, brain injuries, ADHD, and cognitive disabilities of all sorts—any brain that doesn’t think in “conventional” or expected or “neurotypical” ways. In the early days of the Disability Alliance and Caucus, this language allowed us to think both about being neurodiverse (as in, our group contained many neurotypes) and about how each individual one of us was neurodivergent in different ways: neurodiversity is about the aggregate (an individual person cannot be diverse, only a group can be), and neurodivergence is about the individual with respect to an aggregate (people are divergent from some standard or norm).

…

But when autistics are forced to mask and process in the world in ways that make neurotypical people happier, when they are trained to ignore the things that feel good and natural to them, it takes a huge cognitive and emotional toll, especially over time. Autistic people point to consequences of this type of masking: autistic meltdowns (sometimes called tantrums, these are in fact a manifestation of overstimulation—emotional outpourings that help them re-regulate) and autistic burnout (absolute exhaustion and even catatonia that can last for days or years from having to constantly perform as neurotypical). These are some of the results of having your natural behaviors bulldozed in the quest for normality.

…

Bell (1927), 20 Çevik, Kerima, 104 Carter-Long, Lawrence, 27, 28 “Case for Conserving Disability” (Garland-Thomson), 52 Case for Disabled Astronauts, The (Wells-Jensen), 126 cerebral palsy, 91 chapter guide, 12–13 charity marketing campaigns, 36–37 Charles, Ray, 35 chattel slavery, 24 chemobrain, 11–12, 77, 78, 112 Chertock, Marlena, 126 “Choreography for One, Two, and Three Legs” (Sobchack), 138n15 citizenship, 18, 137n6 Claiming Crip (Hitselburger), 30 Clare, Eli, 124 climate change, 115–16, 117 “Clinically Significant Disturbance: On Theorists Who Theorize Theory of Mind” (Yergeau), 140n28 cochlear implants, 71–72 colonization effects, 24–25 concentration camps, 91 congenital amputees, 57 congenital disability, 89 Covid-19, 41, 52, 58, 115, 118, 138n13, 141n38 “crip,” 30 Crip Camp, 30 Crohn’s disease, 4 cross-disability community connections, 12, 77, 78–81, 85–86, 131 cultural technologies, 83, 107–8 Cyborg Jillian Weise, The, 2, 9–10 cyborgs (technologized disabled people), 55 Dancing with the Stars, 49, 60, 61, 63, 64 Deaf community, 71–72, 73 Deaf Gain, 73–74 Deaf Poets Society, The, 125–26 Decolonizing Mars Unconference, 117, 127–28 dehumanization, 88–89, 100, 101–2, 140n28 de Leve, Sam, 126, 130 “Descent” (Kinetic Light Project), 62–63 diabetes, 59, 138nn12–13 Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM), 19, 102 disability conscious acts of empowerment, 28–30 economic categorization of, 24–25 historical framework of, 24–25, 26–27 pathologized approach vs. experiential/relational approach to, 85–86 political/relational contexts within, 88 as predictable human experience, 114–15 as social construct, 21 uncertainty and, 120–24 disability activism, 12, 79 campus accessibility campaigns, 138n7 celebrating disability embodiment and, 62–63 centering disabled people in disabled technology, 17, 110–11 charities garnering activist critique, 92 cross-community coalitions and, 79–80 disability rights, 44, 92, 105 disability rights movement, 27, 28, 31, 56, 92, 109 disability communities amputee community, 3, 12–13, 14–15, 26, 58, 59, 74–75 autistic community, 77, 79–80, 105–6, 112 claiming identity, 28–29 Deaf community, 71–72, 73 framing language of, 25–26, 30, 31 inclusion/diversity of, 22, 82, 115, 124 media generated tropes and, 40, 41–43 nondisabled experts harm to, 10–11, 19–20, 88 principles of justice, 125 representation and, 4, 56, 119 value of, 51, 56, 113, 122, 124, 125 See also neurodivergence disability culture, 107–8 disability experts, 2–3, 10–11, 17, 19–20, 50–51, 100, 123, 131 disability history, 24–25, 26–27, 31, 88–92 Disability History of the United States, A (Nielsen), 23 disability language, 11, 23, 25–26, 30, 31, 72 disability parking, 5–6, 38–39, 78 disability service professionals, 85–86, 95–96 disability and technology centering disabled as experts, 17, 110–11 cultural technologies, 83, 107–8 deterioration and usage, 60 disorientation and, 22–33, 44–45 historical Nazi Germany and, 89–92 insight for technological futures, 123–24, 128–30 media narratives and, 17, 32–33, 35, 50–51, 59, 60–61 medical model of disability and, 71 technoableism, defined, 7–8, 9, 130 technofuturists and, 114, 118–19 technological solutionism and, 4, 8, 9–10, 32, 51–53, 71–72, 74 See also accessible environments Disability Visibility Project, 114 disability welfare, 34, 38 disabled, etymology, 27–28 disabled ecologies, 116 Disposable Humanity (Snyder and Mitchell), 92 Divas with Disabilities Project, 56 Down syndrome, 91 Down Syndrome Uprising, 94 drapetomania, 25 DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual), 19, 102 Dungeons & Dragons, 80, 107, 109 Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (EDS), 85 emotional regulation, 97 enhancement technologies, 51 environmental health hazards, 116–17 environmental racism, 115–16 eugenics history, 89–92 euthanasia, 91 Evans, Dom, 35 exoskeletons, 8, 22, 50, 55 eye contact, 83, 84, 86, 99, 103 Fakorede, Foluso, 58 fatphobia, 17 feel-good narratives, 53–54 Feminine Boy Project, 102 Film-Dis, 35 flappy hands, 96–97 Forber-Pratt, Anjali, 28 forced sterilization, 88, 91 Funk, Cynthia, 56 Fuselier, Annabelle, 112 Gallaudet Eleven, 127, 130 Gardiner, Finn, 97, 106–9 Garland-Thomson, Rosemarie, 28, 52, 68 gay conversion therapy, 102, 103 gender dysphoria, 102 handicapped, 26–27 Hawking, Stephen, 128 Hearing Happiness (Virdi), 71, 73 Heidinger, Willi, 90 Herr, Hugh, 51, 53, 56, 67 Hershey, Laura, 124 Hitler, Adolf, 89, 90 Hitselburger, Karin, 30 Holocaust, 89 Hough, Derek, 61 “I Am Autism” (Wright), 92–93 IDEA (Individuals with Disability Education Act), 26 identity-first language, 25–26 Indian Residential Schools, 24 Indigenous peoples, 23, 24, 25 Individuals with Disability Education Act (IDEA), 26 inspirational-overcomers trope, 41–44, 46–47, 49, 54–55, 60–64, 71–72 inspiration porn, 41–44 institutionalization, 88 intellectual disabilities, 29, 95 Invitation to Dance (Linton), 62, 138n10 James, William, 139n16 Jerry’s Kids, 37 Johnson, Cyrée Jarelle, 124 Johnson, Harriet McBryde, 31, 37 Jones, Keith, 30 Judge Rotenberg Center (JRC), 104–5 Kennedy, John F., 139n23 Kennedy, Rosemary, 139n23 Krip Hop Nation, 30 Lamm, Nomy, 124 Law, Ashtyn, 35 Left Hand of Darkness, The (LeGuin), 120–21 leg amputees, 16, 49, 64–67, 69–70 LeGuin, Ursula K., 120, 121 Leib-Neri, Marisa, 23–24 Lewis, Jerry, 37 Lewis, Talila A., 9 Linton, Simi, 27, 62, 138n10 Little People of America, 94 Long Covid, 41, 52, 115, 118 Lovaas, Ivar, 100–102 Lumumba-Kasongo, Enongo 128 Lyme disease, 119 MacIntyre, Alasdair, 119 Magic Wand, The (Manning), 34 Manning, Lynn, 34–35 McCollins, André, 104–5 McCollins, Cheryl, 104 McLain, Elizabeth, 106–7, 111–12 McLeod, Lateef, 124 media narratives, 17, 32–33, 35, 50–51, 59, 60–61 See also tropes medical experimentation, 91 medical model of disability, 20–21, 31, 71, 139n22 mental illness, 25, 88, 102, 130 Meyer, Bertolt, 55 Milbern, Stacey, 124 Mitchell, David, 92 mobility equipment, 17, 22, 48, 55, 69, 131, 137n5 moochers-and-fakers trope, 38–39, 88–89 Moore, Leroy Jr., 30, 124 movement choices, 16, 62–63 Muscular Dystrophy Association telethons, 37, 92 Nario-Redmond, Michelle, 137n3 National Council on Independent Living, 94 National Institutes of Mental Health, 102 Native American cultures, 23, 24, 25 Nazi Germany, 89–92 Nelson, Mallory Kay, 14, 16, 137n5 neurodivergence addressing social structures, 86–87, 88 applied behavioral analysis and, 95–101, 103–5 Autism Speaks and, 37, 92–93, 94, 95 autistic community and, 77, 79–80, 105–6, 112 autistic scholars panel, 106–12 cross-disability community connections, 12, 77, 78–81, 85–86, 131 cultural technologies and, 83, 107–8 dehumanization and, 88–89, 100, 101–2, 140n28 disability service professionals and, 85–86, 95–96 historical Nazi Germany, 89–92 language of, 84–85 neurodiversity and, 12, 13, 80, 81, 82, 84 neuroqueer, 102 neurotypical and, 81–82, 83 stimming and, 96–97 See also autism spectrum disorder; disability communities neurodiversity, 12, 13, 80, 81, 82, 84 neurodiversity movement, 13, 82 neurodiversity paradigm. See neurodiversity neuroqueer, 102 neurotypical, 81–82, 83 Nielsen, Kim, 23 normative behavior patterns, 110 Not Dead Yet, 94 “nothing about us without us,” 109 Nović, Sara, 71, 72 Ollibean (Sequenzia), 98 Onaiwu, Morénike Giwa, 19 overstimulation, 104 Paralympics, 13 Parastronauts, 128 Patient No More, 31 Pavlov, Ivan Petrovich, 100, 140n29 Peace, Bill, 30, 40, 51, 54, 70 person-first language, 25–26 Peters, Gabrielle, 7 Piepzna-Samarasinha, Leah Lakshmi, 114, 120, 124 Pistorius, Oscar, 49 pitiable-freaks trope, 36–37, 88–89 Plains Indian Sign Language, 23 “Poet with a Cattle Prod” (Lovaas), 102–3 Pokémon, 11, 107, 108 pollution, 115–16 post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), 3, 11, 97, 99 Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS), 85, 118 post-viral syndromes, 52, 118, 141n38 POTS (Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome), 85, 118 Presser, Lizzie, 58 Price, Margaret, 85 professional/expert treatments, 2–3, 10–11, 17, 19–20, 50–51, 100, 123, 131 Project Unicorn, 69 prostheses advanced technology and, 46–47, 49, 50, 68 arms and hands, 67–69 costs of, 16, 66–67 deterioration and usage, 60, 63–64, 139n16 disabled experience vs. media narratives, 53–55, 60, 61, 63 legs and, 64–67 maintenance and, 72, 75–76 personalized requirements of, 15–16 sexual abuse and, 16 technology choices and, 16–17, 69–70 as tools, 14–15, 54 “Prosthetics Do Not Change Everything” (Reeves), 68–69 PTSD (post traumatic stress disorder), 3, 11, 97, 99 Pulrang, Andrew, 30 Purdy, Amy, 49, 61 Quiet Hands (Bascom), 96 racism, 17, 18, 25 Radford Army Ammunition Plant (RAAP), 117 radical empiricism, 139n16 Real Experts, The (Sutton), 19, 106 Reeves, Jen Lee, 8, 68, 139n17 Reeves, Jordan, 8, 139n17 refrigerator mother theory, 41 Rehabilitation Act (1973), 27 rollator, 48, 76 Samuels, Ellen, 85 saneism, 17 Satterwhite, Emily, 117, 141–42n43 #SayTheWord campaign, 28, 29 Schalk, Sami, 42, 43, 85 scientific racism, 17 sensory regulation, 97 Sequenzia, Amy, 98 “Seven Traits for the Future” (MacIntyre), 119–20, 141n39 sexism, 17 sexual abuse, 16 shameful sinners trope, 40–41 Sheppard, Alice, 62 Shivers, Carolyn, 106, 109–10 Singer, Judy, 81 Sins Invalid, 124, 125 Sledge, Heath, 139n16 Snyder, Sharon, 92 Sobchack, Vivian, 138n15 social model of disability addressing social structures, 86–87, 88 disability from societal stigmas/barriers, 22–23 environmental design and, 119–20 vs. medical model of disability, 31, 139n22 neurodiversity/neurodivergence and, 82, 84–85, 139n21 technological solutions and, 71–72 social scripting exercises, 110 Society for Disability Studies, 62 space travel disabling effects, 118–19, 142n50 Spanish Flu (1918), 52 Sparrow, Maxfield, 98–99 spectrum disorder.

Asperger Syndrome: A Love Story

by

Sarah Hendrickx

and

Keith Newton

Published 14 Jun 2007

If, added to this, you have a small or non-existent peer group, it can be impossible to establish if your desires, feelings and practices are ‘normal’ or even acceptable, because there is no one to share with or ask. Given that some people with AS are intensely private and do not share information willingly, this can exacerbate the difficulty. Someone with AS may wonder: How do I know if others with AS experience the same discomforts or pleasures? If I cannot compare myself to the neuro-typical (NT) population, which I do not feel an affinity to, how do I know if I am the only one who feels this way? How do I find a partner if I have no one to ask how to do it? Do others feel the same anxiety, fear and loneliness? Do others feel joy and contentment in their own company? What are the motivations behind relationship choices and sexual behaviour?

…

The whole business of sexuality and interpersonal relations is confusing and fraught with complex and subtle intentions that require decoding (Hénault 2006). 15 16 / Love, Sex and Long-Term Relationships This chapter will focus on how people are finding and choosing potential partners, and it will include comments about how their experiences have affected them. Where to look An initial difficulty may be that someone with AS has a more limited social network than a neuro-typical (NT) person. Some people with AS have no one whom they could describe as a ‘friend’ and, given that any social opportunity is a possible chance of meeting someone, the fewer the social contacts, the fewer the invitations and the fewer the possibilities of finding a partner. We live in a social world full of signs and signals, and assumptions that everyone understands all these.

…

This is an ability that develops in small children who, as they grow, begin to realise that they are not the only people in the world, and that others have different thoughts and knowledge from their own. Many adults with AS can find it very difficult to anticipate and comprehend that a partner may have different emotional needs. Many AS people express bewilderment at the emotional reactions of their neuro-typical (NT) partners. They may 31 32 / Love, Sex and Long-Term Relationships choose to do nothing in response to emotional outbursts rather than risk doing the wrong thing and unwittingly upsetting their partner further. Often the ‘doing nothing’ is exactly what makes things worse because this can be perceived as uncaring and cold to an NT partner.

Explaining Humans: What Science Can Teach Us About Life, Love and Relationships

by

Camilla Pang

Published 12 Mar 2020

Being embarrassed in public is one of the great human fears. I didn’t always know this, but I do now. Saying or doing the wrong thing is something that both neurotypical and neurodiverse people are evidently capable of, but we probably get there via slightly different means. For someone like me, it’s usually through a lack of understanding about social norms and failing to take into account the invisible parameters of hierarchy and convention. If you’re neurotypical, you might have suffered the opposite problem: assuming that your knowledge of a certain situation was enough to ‘get it right’, or overreaching because you felt too comfortable and made a bad joke, or inappropriate suggestion.

…

By understanding scientific principles, we can better understand our lives as they really are: the source of our fears, the basis of our relationships, the functioning of our memory, the cause of our disagreements, the instability of our feelings and the extent of our independence. Science has been the key to unlocking a world whose door was otherwise closed to me. And I believe the lessons it has to teach are important for all of us, whether neurotypical or neurodivergent. If we want to understand people better, then we actually need to know how people work: the functioning of the body and the natural world. The biology and physical chemistry that most of us have only glimpsed as diagrams in a textbook actually contain personalities, hierarchies and communications structures all of their own – reflecting those we experience in everyday life, and helping to explain them.

…

Because of all the privileges I have had in life, I want to share my experiences of what is possible, and what can be achieved from a starting point of difference. With my Asperger’s syndrome, often referred to as a high-functioning form of autism that makes you too ‘normal’ to be stereotypically autistic, and too weird to be neurotypically normal, I see myself as an interpreter between both worlds in which I have lived. I also know that what changed my life was being aware that I was seen and understood. Realizing that I was a person, and had the right to be myself: in fact the duty to be. Everyone has the right to human connection – to be heard and taken seriously.

Visual Thinking: The Hidden Gifts of People Who Think in Pictures, Patterns, and Abstractions

by

Temple Grandin, Ph.d.

Published 11 Oct 2022

I get lost when verbal information is presented too fast. Imagine how a student who is a visual thinker feels in a classroom where a teacher is talking fast to get through a lesson. The New Normal These days, “neurotypical” has replaced the term “normal.” Neurotypicals are generally described as people whose development happens in predictable ways at predictable times. It’s a term that I shy away from, because defining what is neurotypical is as unhelpful as asking the average size of a dog. What’s typical: a Chihuahua or a Great Dane? When does a little geeky or nerdy become autistic? When does distractable become ADHD, or when does a little moody become bipolar?

…

Neurologist and author Oliver Sacks picked up on this propensity of mine to gather information and wrote about it in a New Yorker article that then became the title of his book An Anthropologist on Mars. It was an accurate description of how I make sense of the world. I’m like Margaret Mead among so-called normal, or “neurotypical,” people. In lieu of certain kinds of social connection, I’m more comfortable studying the ways and habits of people. “Fitting in” is a complicated business. I didn’t realize it then, but in searching for fellow visual thinkers through my survey, I was also searching for my tribe. I started my survey by asking people to describe their home or their pet.

…

Using what is known as the Children’s Embedded Figures Test, the researchers administered four separate cognition and intelligence evaluations to thirty autistic children with low verbal skills and an age-matched control group. While none of the autistic kids were able to complete the standard intelligence test (Wechsler Intelligence Scale), twenty-six completed the Embedded Figures Test, and they finished it faster than matched neurotypicals. Laurent Mottron, in a Nature article, reports that autistic people display more activity in the visual-processing network than the speech-processing network of the brain. He writes, “This redistribution of brain function may nonetheless be associated with superior performance.” The challenge is in how to offer a more effective assessment and education to visual-object thinkers.

The Asperger Love Guide: A Practical Guide for Adults With Asperger's Syndrome to Seeking, Establishing and Maintaining Successful Relationships

by

Genevieve Edmonds

and

Dean Worton

Published 15 Dec 2005

This is in contrast with the wealth of literature available for neurotypical people – just one of a multitude of examples of how poorly recognized, understood, and supported the needs of people with AS are. It is the duty of a just society to ensure that with the passage of time these needs are met, and from the perspective of people with AS and their families, the sooner the better. With written accounts by people with AS becoming more widely published the platform upon which to build better and more appropriate support services will grow stronger. It is then down to the neurotypical population to learn from the growing literature, and to use that platform to provide that support as and when it is needed.

…

This refers to an able, high functioning adult with Asperger’s syndrome, however, the book can be used for lower functioning adults on the autistic spectrum with support from a support worker, carer or trusted friend. NTs – a term used for the purposes of writing referring to mainstream neurologically ‘normal’ (neurotypical) individuals. AS – Asperger’s syndrome. Partner – a general term used for the purpose of writing for boyfriend, girlfriend or mate and to avoid cultural, sexuality, racial, regional, gender and related differences. ASD – Autistic Spectrum Disorder. Stims – self-stimulatory behaviour: repetitive motor or vocal mannerisms engaged in by people with ASDs.

…

I suppose with no experience of either situation, then I cannot say for sure and of course, everyone is different, AS or not. My general thoughts are that I feel a relationship with an understanding person, without AS, would be preferable. When I’m functioning well, I am able to socialize comfortably with neurotypical friends and acquaintances and I imagine that having a partner who is slightly more outgoing than me could be beneficial for me. 70 Until I became a university student, I attended an all-boys school between the ages of 12 and 18. Before 12, I wasn’t really mature enough to understand the concept of love and relationships, however, since coming to university this issue has led me into a lot of depression.

For the Love of Autism: Stories of Love, Awareness and Acceptance on the Spectrum

by

Tamika Lechee Morales

Published 23 Apr 2022

While a few friends will come to you and give you a hug, ask you how your child is doing, how school is, or offer to have a coffee, many may not know what’s happening or how to react. Now, my son is a teenager, and he has different interests and needs: music, friends, outings, parties. He has never been invited to neurotypical party. He does not know what that is. Instead, we would invite “regular kids” (neurotypical ones) to our house. We have been blessed that Jose Maria has a few friends who understand his difference but challenge him. These friends focus on strong conversation, redirect Jose Maria so he is present, paying attention, understanding what he understands, and sharing what he wants to share.

…

Legend loves the spotlight and a video camera. He has been begging for his own YouTube channel, so I love to turn the camera on him and have him improv. He has great presence and is truly a natural. It’s fun to watch him and I can’t help but feel amused every time. I also look at it as him practicing public speaking skills, which even neurotypicals are fearful of doing. One year, we sponsored an Autism’s Got Talent and Resource Fair through The Autism Hero Project, and I wanted to do a mommy-and-son dance to Kelly Clarkson’s song, “Broken and Beautiful.” We only practiced a few times because I was so consumed with all of the details and organization of the event itself.

…

Had Mustafa become just another statistic for their records? Unfortunately, no systems were in place to guide and support us. We were left grieving the “typical” child we thought we had lost. Needless to say, I didn’t know where to begin. At the time, I was a preschool teacher and had studied early childhood development, so I understood how neurotypical children developed. However, I didn’t know how to work with children with special needs. KNOWLEDGE IS THE MOST POWERFUL TOOL I knew I had to do something, so I searched for therapies. He isn’t speaking, so he must need speech therapy, I thought. We contacted a clinic and once a week I would sit in their office after work until 8:30 p.m. so that Mustafa could take part in speech therapy, occupational therapy, and physical therapy.

Player One

by

Douglas Coupland

Published 30 Jun 2011

Rachel has never fit into the world. She remembers as a child being handed large wooden numbers covered in sandpaper to help her learn numbers and mathematics. Other children weren’t given tactile sandpaper number blocks, but she was, and she knows that she has always been a barely tolerated sore point among her neurotypical classmates. Rachel also remembers many times starving herself for days because the food that arrived at the table was the wrong temperature or colour, or was placed on the plate incorrectly: it just wasn’t right. And she remembers discovering single-player video games and for the first time in her life seeing a two-dimensional, non-judgemental, crisply defined realm in which she could be free from off-temperature food and sick colour schemes and bullies.

…

It’s much easier to determine a woman’s age, as nature is far more generous in offering visual prompts in that department. Seated at the bar was another man — early thirties? He appeared well-nourished, and Rachel tried to determine whether he was handsome. “Handsome” is the male equivalent of beautiful, and to neurotypicals handsomeness indicates good breeding stock. Having studied copies of InStyle magazine for years, trying to understand the language of looks, Rachel remained unable to calibrate any rules of attractiveness. On the other hand, the man at the bar, who had had two drinks since he had arrived, kept two large rolls of money in his jacket pocket.

…

But now he believes that time has floods, too — it simply isn’t a constant anymore. Twenty thousand dollars in his pockets, and Luke feels like he’s in the flood. Luke asks, “What about you? Single?” “Yes. Irregularities in the insula, cingulate, and inferior frontal parts of the brain make me unable to have what neurotypical people such as you call a ‘relationship.’ I enjoy situations that are familiar to me, and if that means having a person around me, then I suppose that’s fine. But it’s not something I crave or seek. I also have 630 people following my ongoing blog on the subject of mouse breeding. One might consider them, if not partners, then friends.

Neurodiversity at Work: Drive Innovation, Performance and Productivity With a Neurodiverse Workforce

by

Amanda Kirby

and

Theo Smith

Published 2 Aug 2021

This is defined as one whose neurological development and state are atypical or diverge from the dominant neurological, cognitive and behavioural norms. The term has been thought to have been generated by the neurodiversity movement and initially focused far more on autistic people. It was seen as the opposite to ‘neurotypical’. However, using the term in this way may cause challenges of ‘otherness’ and sets people up as being either neurotypical OR neurodivergent, ie either sitting in one camp or another, when in reality people are far more complex and nuanced and cognition is far more than representing just one domain. The term divergence is also defined as separating, changing into something different, or having a difference of opinion.

…

Personality assessments can also provide useful information, but they aren’t nearly as powerful as other tools and often have the problem of being developed on a neurotypical population. There is a challenge also that taking grades and years of education as a metric for skills can exclude those whose education may have been a bit bumpy. In reality, combining multiple selection methods can help provide a comprehensive picture of candidates’ ability to perform well in the position you’re hiring for. There is some evidence of the challenges of using some assessments that have not been validated on a wider population, including those who are neurodivergent.5 Hiring diverse talent If using psychometric assessments is the norm for neurotypical people, is this the right thing if you actually want to attract a neurodiverse talent pool?

…

So neurodiversity is… the beautiful reality that all our brains are unique and we should start to celebrate and embrace that fact more often, and not allow language or labels to determine what’s normal and what’s not! Amanda’s normal is living in a very varied neurodivergent family – this is her neurotypical! In the end we want to have the tools and confidence to empower each of us to be our best selves. Warning: words have different meanings to different people at different times Human evolution, the distinction between us and our pets at home, is the fact we use language and words to communicate like no other being on this planet.

Autism Adulthood: Strategies and Insights for a Fulfilling Life

by

Susan Senator

Published 4 Apr 2016

Paul lent them his car wash, and in nine weeks over the summer, Tom recruited, trained, and employed fifteen young people with autism. They bought their first car wash a few months later, renovated it, and employed thirty-five guys with autism; they’ve been operating since then. Since opening, they have quadrupled their business, and they are profitable. Using supervisors who are neurotypical, Rising Tide manages to provide great job support for the employees with autism. Tom found that they did not need to give any special autism training to the supervisors; that the supports came naturally over time because the managers got to know their employees. Tom told me that he is, however, currently working on a “‘management guide’ for coaching and leading people with autism.

…

“I tell the clients ‘so-and-so is going to work with you, so you have to be a little more patient.’” Relationships, whether between a caregiver and a person who has a disability, or anyone else, are a two-way street. Perhaps this is the key to John’s great track record with Nat. As much as I hate to say it, too often we neurotypicals sometimes forget that our autistic loved ones are full-blown people, with all the quirks, irritations, emotions, flaws, hopes, and dreams that we have. Accordingly, John fully expects the individuals to do their part to form a successful relationship with the staff, to the extent they can. “Both the individuals and the staff have to be patient,” he said.

…

Therefore it is important to ask whether this autistic student actually needs this skill at this time. “We need to look at ways he can acquire skills that are of intrinsic value to him right now,” Peter says. In other words, we cannot take it for granted that autistic people will automatically value skills that neurotypical people value. Aim for the greatest efficiency of skill acquisition Another factor in teaching autistic people a particular skill is to consider how easy it is to put that skill in place. How much energy do you want to devote to this effort? Is there a natural context in which to learn this skill?

Autism: A Very Short Introduction

by

Uta Frith

Published 22 Oct 2008

Edward sticks out in a crowd, not only by his tall and lanky appearance, but also by his mannerisms and loud high-pitched voice. However, he has started to read books of manners and body language and is hoping they will improve his social skills. Edward is very knowledgeable about Asperger syndrome and avidly participates in Asperger discussion forums on the web. He knows that he is far more intelligent than most ‘neurotypicals’. However, there are signs that Edward is often anxious and sometimes depressed, and he is being seen by a psychiatrist who will carefully monitor him in the transition period when he leaves home to go to college. The three core features of the autism spectrum The examples of David, Gary, and Edward show how enormously varied the core signs of autism are, at least on the surface.

…

Is it indeed a form of autism and with the same genetic causes as autism? Or is it merely a personality type and not a disorder? There are now a number of people who have diagnosed themselves as having Asperger syndrome. These individuals often call themselves Aspies, and they feel different from NTs or neurotypicals. They do not need the attention of a clinician. They are perfectly adapted in their everyday lives, occupying a niche that is just right for their special interests and skills. It is not surprising that these people argue that Asperger syndrome is not a disorder. To them it is merely a difference, and a difference to be proud of.

…

Imagine if you were unable to do this. You would surely think the world of people complicated and unpredictable. Here is an extract from what an anonymous person with Asperger syndrome wrote: Something that most of us find difficult to remember is to whom we have said something and to whom not. Neurotypical people seem to be able to keep a mental file or record for every person they know with minute details, down to the fibs that have been said along with a mental note to keep them in mind. One of the most important things about the world of people is faces. And in faces it is the eyes that attract our attention.

The Behavioral Investor

by

Daniel Crosby

Published 15 Feb 2018

This is the line of thought pursued in a Stanford University study titled, ‘Investment Behavior and the Negative Side of Emotion’. Within, the researchers pitted 15 individuals with brain damage to their emotional processing centers against 15 “neurotypical” peers in a gambling task. The study found that the brain damaged participants handily outperformed their no-damage counterparts through a combination of being willing to take bigger bets and being able to bounce back quickly after setbacks. The neurotypical participants played more safely throughout but became particularly risk averse after periods of poor performance (which in markets tend to coincide with attractive periods of investment).

…

Incredibly, the choice supportive bias is such a powerful tendency that it seems to exist somewhere so deep within us that it is even present in those unable to form short-term memories. Dan Gilbert and his team examined the impact of the Free Choice Paradigm on a group of subjects with anterograde amnesia; in other words, a group of hospitalized individuals unable to form new memories. Like their neurotypical (that is, without brain damage) peers, the amnesiac patients were asked to rank the paintings from 1 to 6 and were given the option to keep either painting 3 or 4. Upon choosing a painting, the researchers promised to mail the chosen painting in a few days and left the room.30 Returning just 30 minutes later, the members of Dr.

…

To ensure that the amnesic patients were truly unable to form memories, the researchers then asked them to point to the painting that they had chosen before, a task at which the patients performed less well than chance guessing! The patients were then put through the whole ranking exercise again, with astonishing results. Just as with the neurotypical control group, the amnesic patients “talked up” the choice they made and dismissed the painting not chosen, even though they had no memory of having made a choice at all! Our need to view ourselves as competent and maintain ego lives somewhere so deep within us that not even cognitive impairment can touch it.

Black Pill: How I Witnessed the Darkest Corners of the Internet Come to Life, Poison Society, and Capture American Politics

by

Elle Reeve

Published 9 Jul 2024