Richard Dawkins: How a Scientist Changed the Way We Think

by

Alan Grafen; Mark Ridley

Published 1 Jan 2006

Recently the journal Biology and Philosophy ran three articles by Kevin Laland, J. Scott Turner, and Eva Jablonka discussing the impact on biology of Richard’s book, The Extended Phenotype, after it was published in 1982. I was much enjoying reading Richard’s response until I came to a scarcely veiled attack on my ‘obscurantism’. With friends like that who needs enemies! Richard referred to my ‘superficially amusing but deeply misleading suggestion that a gene is a nest’s way of making another nest’. It related to a passage in my review of The Selfish Gene. It is worth quoting the passage since the fidelity of the replication has suffered from Chinese Whispers, about which Richard writes so well, and, more seriously, my intent had been corrupted over time.

…

What are the agents of differential survival and differential reproductive success? What are the necessary conditions for recreating successful characteristics in the next generation? Simplicity and Complexity Richard recently had a go at me when he discussed the abuse of the term epigenetics which, he claimed, ‘has become associated with obscurantism among biologists’. This is followed by a reference to a footnote which reads: ‘I am reminded of a satirical version of Occam’s Razor, which my group of Oxford graduates mischievously attributed to a rival establishment: “Never be satisfied with a simple explanation if a more complex one is available.”

…

Griffith-Thomas: ‘It commences with the conviction of the mind based on adequate evidence; it continues in the confidence of the heart or emotions based on conviction, and it is crowned in the consent of the will, by means of which the conviction and confidence are expressed in conduct.’ Such a definition—which McGrath describes as ‘typical of any Christian writer’—is what Dawkins, in reference to French postmodernists, calls ‘continental obscurantism’. Most of it describes the psychology of belief. The only clause of relevance to a scientist is ‘adequate evidence’, which raises the follow-up question, ‘Is there?’ Dawkins’ answer is an unequivocal ‘No’. * * * Does a scientific and evolutionary world view such as that proffered by Richard Dawkins obviate a sense of spirituality?

The Accidental Theorist: And Other Dispatches From the Dismal Science

by

Paul Krugman

Published 18 Feb 2010

This is not to deny that much of what modern economists (or academics of any type) do is pointless technical showboating, using fancy math to say things that could just as well have been expressed in plain English—or for that matter to say things that would be obviously silly if their meaning were not obscured by the math. But not all of the technicality of modern economics is obscurantism; sometimes it is actually a way to make things clearer and simpler. Still, there should be a lot more accessible, interesting, even exciting writing about economics than there is. Astronomy is a difficult, technical subject, too; yet where is the economics equivalent of the late Carl Sagan? (Did you know that U.S. consumers spend trillions and trillions…never mind.)

…

Of course these sensible central banks will deny that they follow any such strategy. This is understandable. Anyone who has watched the press pounce on a novice central banker naive enough to speak plainly realizes why more experienced hands, however well-intentioned and clear-headed, prefer to cloak their actions in obscurantism and hypocrisy. But while hypocrisy has its uses, it also has its dangers—above all, the danger that you may start to believe the things you hear yourself saying. This is not a hypothetical possibility. Right now there are important central banks—the Banks of Canada and France are the obvious examples—which really seem to believe what they say about wanting stable prices; their sincerity is costing their nations hundreds of thousands of jobs.

Lotharingia: A Personal History of Europe's Lost Country

by

Simon Winder

Published 22 Apr 2019

But within Lotharingia ‘county’ could mean something ranging from the very grand (the County of Holland; the County of the Mark) to a soggy dot (the County of Bentheim) and being count in these places could either be a very serious role or a bit of a joke. Dukedoms were more senior in the hierarchy, but did not necessarily imply more significant territories: the Duke of Bar (on the border with France) or of Fürstenburg (in the Black Forest) had many fewer resources than the major counts. But that is probably enough obscurantism for one section – the book can return to the western exclaves of the Duke of Württemberg later on. Sticking to the post-Treaty of Ribemont world of 880, this was the last partition of what was still recognizably Charlemagne’s inheritance. It enshrined Lotharingia – Middle Francia – as a huge zone which both the French king and German king could equally lay dynastic claim to.

…

In even the short term the British seemed oddly undamaged by this – certainly humiliated, but with the rest of their empire intact and with continuing cultural, linguistic and financial links to the United States which France could not break. It was though the republican bit that was most striking. Republics had been small historical oddities – the Swiss, stagnant Venice, some bits of religious obscurantism inside the Holy Roman Empire such as the Abbey of Essen – and now they suddenly seemed chic, big scale and workable. As the Dutch wound up their war with the British, they looked askance too at the hapless William V, who while not a monarch was, as hereditary Stadtholder, close enough. He was so widely despised that he managed to be both personally against the war and yet blamed for its disasters.

…

Some local cafe chat about how it might have made more sense for Savoy to join the Swiss Federation was rapidly quashed by French troops. Evian aside, it had the unfortunate effect of making Britain again absolutely hostile to France – the British seeing Napoleon now not as the quixotic liberal supporter of Italian unification over Austria’s fossil obscurantism, but as an acquisitive adventurer in the same mould as his uncle. The 1848 revolutions and the Italian wars, combined with extensive colonial activity, made all borders seem up for grabs and Napoleon III was central to this sense of the tree being shaken to see what fell out. While blithely interfering in Mexico and sending soldiers to Asia, Napoleon had unfortunately failed fully to take on board the significance of Otto von Bismarck, who became Minister President of Prussia in 1862.

Cows, Pigs, Wars, and Witches: The Riddles of Culture

by

Marvin Harris

Published 1 Dec 1974

The exercise of the freedom of belief in the laboratory could only be a temporary inconvenience until the charred remains of superconscious experimenters were swept out along with the rubble they created. Unfortunately, obscurantism applied to lifestyles does not self-destruct. Doctrines that prevent people from understanding the causes of their social existence have great social value. In a society dominated by inequitable modes of production and exchange, lifestyle studies that obscure and distort the nature of the social system are far more common and more highly valued than the mythological “objective” studies dreaded by the counter-culture. Obscurantism applied to lifestyle studies lacks the engineering “praxis” of the laboratory sciences.

What's Left?: How Liberals Lost Their Way

by

Nick Cohen

Published 15 Jul 2015

Many were post-modern academics employed by the states they presumably wanted to topple to teach ‘theory’ in Western universities. Anderson did not realize that their infamous obscurantism was a sign of their cowardice as well as their political isolation. Writers write badly when they have something to hide. Clarity makes their shaky assumptions plain to the readers – and to themselves. By keeping it foggy they save themselves the trouble of spelling out their beliefs and recommendations for the future. For academics, of all people, this is a disreputable way of going about business, but one that has many uses. Obscurantism spared the theorists who emerged from the grave of Marxism the pain of testing dearly held beliefs and prejudices, as well as the inevitable accusations of selling out from friends and colleagues a clear-headed revision of their ideas would bring.

…

Feminists are targeting India and ignoring America because they are the lackeys of the world’s only superpower and its imperialist values [‘serving the hegemonic’]. It is racist to oppose sexists. Leave aside for the moment that what he was saying was a slur – feminists in America and around the world had turned domestic violence from a private torment to a public crime – and marvel at the transformation. The theorists’ obscurantism marked the conclusion of the strange story of the 1968 generation of radicals, many of whom ended up standing on their heads and using the language of the Left to justify the far right. When they were young, of course, nothing could have been further from their minds. Their real achievements had little to do with the socialism so many of them espoused.

A History of Zionism

by

Walter Laqueur

Published 1 Jan 1972

Despite the reimposition of restrictive laws, social assimilation made rapid progress during the early decades of the nineteenth century. Many Jews moved from the villages into larger towns, where they could find better living quarters; they sent their children to non-Jewish schools and modernised their religious service. Among the intellectuals there was a growing conviction that the new Judaism, purged of medieval obscurantism, was an intermediate stage towards enlightened Christianity. They argued that the Jews were not a people; Jewish nationhood had ceased to exist two thousand years before, and now lived on only in memories. Dead bones could not be exhumed and restored to life. Jewish spokesmen claimed full equality as German citizens; they were neither strangers nor recent arrivals; they had been born in the country and had no fatherland but Germany.

…

Rabbi Emden of Altona claimed that the amulets sold by Rabbi Eybeschütz of Hamburg to pregnant women (they were supposed to have a magic effect) included a reference to Shabtai Zvi; this was the great confrontation shaking central European Judaism for many years. With the keepers of the faith engaged in disputations of this kind, was it surprising that the Jewish readers of Voltaire had little but derision for what they regarded as the forces of obscurantism? Much of the influence of the Enlightenment was shallow and its fallacies were demonstrated only too clearly in subsequent decades. But in the clash between secularism and an ossified religion based largely on a senseless collection of prohibitions and equally inexplicable customs elaborated by various rabbis in the distant past, there was not the slightest doubt which would prevail.

…

Some populist groups had played a certain part in stirring up anti-Jewish sentiments during the early phase of these attacks, on the mistaken assumption that riots against ‘Jewish parasites’ would eventually turn into a revolutionary movement directed against the government, the landowners and capitalists. The main instigators, especially during the later period, were the ‘Black Hundred’ and other movements of the extreme Right, which preached a mixture of extreme nationalism and religious obscurantism. The tsarist government was rightly accused of aiding and abetting the pogromists in the hope of diverting popular dissatisfaction. But anti-semitism was not manufactured by the administration or forced upon an unwilling or indifferent population. It had deep roots among at least part of the population, and not much encouragement on the part of the authorities was needed to kindle the flame of race hatred.

Revolution Française: Emmanuel Macron and the Quest to Reinvent a Nation

by

Sophie Pedder

Published 20 Jun 2018

It may also require a less rigid application of the French secular creed of laïcité, which separates religion and public life, in a way that is not felt by the country’s Muslims to be stigmatizing. Entrenched by law in 1905, this principle was the product of a long anti-clerical struggle with the Catholic Church and the forces of obscurantism. It formed the basis for the French ban on the wearing of the burqa in public, and the headscarf (and other ‘conspicuous’ religious symbols) in state classrooms. At times, the country’s ultra-secularists push laic principles to illiberal excess. After the Nice terrorist attack of 14 July 2016, some mayors in beach resorts tried to ban the ‘burkini’, before being overruled in the courts.

…

The French love grands projets, and this speech was full of them: a shared European military budget, a European intelligence academy, a joint intervention force based on a ‘common strategic doctrine’, a European asylum office, a new agency for ‘radical innovation’, six-month exchanges for young people, an environmentally friendly carbon tax at the EU’s external border, a ‘trade prosecutor’, a eurozone budget and finance minister, fiscal harmonization, and more. If this speech was more technical, its impulse was nonetheless political. Macron reminded his audience that the ‘sad passions’ inflamed by ‘obscurantism’ were being awakened across the continent. Europe’s leaders, by blaming Europe when things went wrong and failing to give it credit for success, had to accept responsibility for having created the conditions for such forces to prosper. The overarching message at the Sorbonne was threefold: that Europe needs to revive its democratic legitimacy; shore up its unity after a period of damaging division; and assert a new form of European sovereignty that will enable it to defend its values in the face of American clout and an assertive China.

The Lessons of History

by

Will Durant

and

Ariel Durant

Published 1 Jan 1968

Shall we count it a trivial achievement that famine has been eliminated in modern states, and that one country can now grow enough food to overfeed itself and yet send hundreds of millions of bushels of wheat to nations in need? Are we ready to scuttle the science that has so diminished superstition, obscurantism, and religious intolerance, or the technology that has spread food, home ownership, comfort, education, and leisure beyond any precedent? Would we really prefer the Athenian agora or the Roman comitia to the British Parliament or the United States Congress, or be content under a narrow franchise like Attica’s, or the selection of rulers by a praetorian guard?

The Four Horsemen

by

Christopher Hitchens

,

Richard Dawkins

,

Sam Harris

and

Daniel Dennett

Published 19 Mar 2019

But they aren’t systematically incomprehensible to human beings. The glorification of the idea that these things are systematically incomprehensible I think has no place in science. HITCHENS: Which is why I think we should be quite happy to revive traditional terms in our discourse, such as ‘obscurantism’ and ‘obfuscation’, which is what they really are. And to point out that these things can make intelligent people act stupidly. John Cornwell,*24 who’s just written another attack on yourself, Richard, actually, and who is an old friend of mine, a very brilliant guy, wrote one of the best studies of the Catholic Church and fascism that has been published.

A History of Judaism

by

Martin Goodman

Published 25 Oct 2017

The term sefirah, which means literally ‘enumeration’ and was to acquire great importance in later Jewish mysticism (see below, here), evidently had some mystical significance for the author of this text, but the style of the book is so allusive that it is hard to know exactly what he intended to convey. The obscurantism may have been deliberate. It certainly did not prevent the text becoming popular. Equally embedded in rabbinic discourse was astrology, with frequent references in the Talmuds to the mazal, ‘planet’ or ‘luck’, of individuals, despite the hostility of those, like R. Yohanan in the third century, who asserted that ‘Israel has no planet’.

…

Yehudah, who wrote a straightforward halakhic code in Worms for the benefit of Jews in Germany and northern France, was in tension with the originality and innovativeness of those rabbis who devoted themselves to hiddushim which constantly expanded the halakhah. The codifiers did not hide their frustration at what they saw as the obscurantism of their rabbinical colleagues who delighted in complicating the law under which Jews did their best to live in piety. Yaakov b. Asher complained in the first half of the fourteenth century that ‘there is no law that does not have difference of opinions.’ His own father, Asher b. Yehiel, known as the Rosh, had produced an influential halakhic compendium which covered all halakhic practice of the time both for Germany (where the Rosh had studied) and in Toledo in Spain, where he became head of the rabbinic academy in 1305, but in the view of Yaakov too much uncertainty remained.

…

Pfefferkorn, coached by the Dominicans of Cologne, attacked the Talmud and demanded that the emperor Maximilian authorize the confiscation of all Jewish books apart from the Bible. When he was opposed by Reuchlin, the two sides engaged in a pamphlet war of extraordinary vitriol and a great deal of personal abuse on both sides. It was not accidental that Martin Luther’s theses were posted in Wittenberg in 1517 at the height of the controversy, in which the obscurantism of elements in the Church had been so effectively revealed by Reuchlin’s supporters, who included many of the leading humanists of the day. Both Reuchlin (who intervened to help the Jews of Pforzheim) and Luther originally condemned the persecution of the Jews as well as the confiscation of rabbinic literature.

The Shipwrecked Mind: On Political Reaction

by

Mark Lilla

Published 19 Oct 2015

Rediger is a marvelous creation—part Mephisto, part Grand Inquisitor, part shoe salesman. His speeches are psychologically brilliant and yet wholly transparent. The name is a macabre joke: it refers to Robert Redeker, a French philosophy teacher who received credible death threats after publishing an article in Le Figaro in 2006 calling Islam a religion of hate, violence, and obscurantism—and who has been living ever since under constant police protection. President Rediger is his exact opposite: a smoothie who writes sophistical books defending Islamic doctrine, and has risen in the academic ranks through flattery and influence-peddling. It is his cynicism that, in the end, makes it possible for François to convert.

A Culture of Growth: The Origins of the Modern Economy

by

Joel Mokyr

Published 8 Jan 2016

His insights more than ever confirmed the belief in a mechanistic, understandable universe that could and should be manipulated for the material benefit of humankind. In some form, the anthropocentric idea of nature in the service of humans had been around since the Middle Ages, but what counted was its triumph over what their proponents regarded as obscurantism and superstition. Seventeenth-century science prepared the ground for the Industrial Enlightenment by stressing mankind’s relationship with the environment as based on intelligibility and instrumentality. In Newton’s work the emphasis is on mathematics and instrumentality, not on explaining the “deep” causes of things (Dear, 2006, pp. 37–38).

…

Galileo did some of his best work at the University of Padua, as did Andreas Vesalius; it counted both William Harvey and Nicolaus Copernicus among its graduates.13 For much of the period between 1500 and 1700, it was the best university in Europe, and the government of Venice bent over backward to accommodate its distinguished if opinionated faculty and protected them from papal and Jesuit obscurantism. The University of Leyden in its golden age in the first half of the eighteenth century was perhaps the most dynamic and successful institution spreading the new Newtonian physics and cutting-edge medicine. In Britain the eighteenth-century Scottish universities famously became a center of innovation in science, political philosophy, medicine, and many other areas.

…

They supported the basic Enlightenment idea of an agenda to bring about economic improvement through an aggressive manipulation of natural forces made possible by useful knowledge. These ideas, in some form, had been around since the Middle Ages, but what counted was their triumph over what progressive intellectuals regarded as obscurantism and superstition. Religious warfare had been shown to have been a rather futile and destructive endeavor, and a growing number of people were advocating the need for religious tolerance rather than pious conformity. By the late seventeenth century such political philosophers as Locke were starting to lay out the parameters of a set of political institutions that could make their world a better and more prosperous place.

Bit by Bit: How P2P Is Freeing the World

by

Jeffrey Tucker

Published 7 Jan 2015

If you seek a clear definition of ideas like freedom or property rights in Hayek’s work, you will come away disappointed. He often seemed so consumed by the complexity of the world that he shied away from clarity for fear that he had missed something. For readers looking for ironclad deductions and arguments, his approach can give the impression of being an elaborate display of obscurantism. In order to understand Hayek and to learn from him, you have to be prepared to think alongside him as he writes. His work presumes an open mind that is ready to think about complex topics, most often from the inside out. He is asking and seeking to answer a completely different set of questions than most people are even willing to consider.

Science in the Soul: Selected Writings of a Passionate Rationalist

by

Richard Dawkins

Published 15 Mar 2017

It has become a commonplace that, were he to return today, he would be appalled at what is being done in his name by Christians ranging from the Catholic Church with its vast and ostentatious wealth to the fundamentalist religious right with its stated doctrine, explicitly contradicting Jesus, that ‘God wants you to be rich’. Less obviously but still plausibly, in the light of modern scientific knowledge, I think he would see through supernaturalist obscurantism. But, of course, modesty would compel him to turn his T-shirt around to read ‘Jesus for Atheists’. AFTERWORD This essay is worded on the assumption that Jesus was a real person who existed. There is a minority school of thought among historians that he didn’t. They have a lot going for them.

…

* * * * The Washington Post used to have a regular feature called ‘On Faith’, moderated by Sally Quinn, to which I was a frequent contributor. This is the opening paragraph of a piece that appeared on New Year’s Day, 1 January 2007, in response to a question on the current vogue for atheism. Dawkins’ Laws* Dawkins’ Law of the Conservation of Difficulty Obscurantism in an academic subject expands to fill the vacuum of its intrinsic simplicity. Dawkins’ Law of Divine Invulnerability God cannot lose. Lemma 1: When comprehension expands, gods contract – but then redefine themselves to restore the status quo. Lemma 2: When things go right, God will be thanked.

The Portable Atheist: Essential Readings for the Nonbeliever

by

Christopher Hitchens

Published 14 Jun 2007

After being worsted in astronomy, they did their best to prevent the rise of geology; they fought against Darwin in biology, and at the present time they fight against scientific theories of psychology and education. At each stage, they try to make the public forget their earlier obscurantism, in order that their present obscurantism may not be recognized for what it is. Let us note a few instances of irrationality among the clergy since the rise of science, and then inquire whether the rest of mankind are any better. When Benjamin Franklin invented the lightning rod, the clergy, both in England and America, with the enthusiastic support of George III, condemned it as an impious attempt to defeat the will of God.

…

It has become a commonplace belief that, were he to return today, he would be appalled at what is being done in his name, by Christians ranging from the Catholic Church to the fundamentalist Religious Right. Less obviously but still plausibly, in the light of modern scientific knowledge I think he would see through supernaturalist obscurantism. But of course, modesty would compel him to turn his T-shirt around: “Jesus for Atheists.” Cosmic Evidence From God: The Failed Hypothesis VICTOR STENGER The majority view of the atheist school is that the existence of god can neither be proved nor disproved, and that therefore the theistic position must collapse because its adherents must claim to know more than anyone can possibly know (not just about the existence of a creator, but about his thoughts on sex, diet, war, and other matters).

Masters of Mankind

by

Noam Chomsky

Published 1 Sep 2014

The appeal to Christian faith may provide spiritual sustenance to those who choose to follow Niebuhr’s path, but nothing more can be claimed, and one who does not feel comforted by arbitrary faith in this or that—and Niebuhr offers nothing more—will persist in seeking truth and justice, with full recognition of the fact—indeed, the banality of the observation—that much lies beyond our grasp, and that this condition will persist for all of human history. It is all too easy to mistake obscurantism for profundity. Niebuhr won renown not only as a thinker but also as a participant in social and political affairs, and his life was indeed one of continuous engagement, in his writings, preaching and lecturing, and other activities. Turning to his writings in these domains, we find essentially the same qualities: no rational person could be convinced since evidence is sparse and often dubious, it is difficult to detect a thread of argument, and he keeps pretty much to the surface of the issues he addresses.

Strange Rebels: 1979 and the Birth of the 21st Century

by

Christian Caryl

Published 30 Oct 2012

The reality was that the newly elected Polish pope’s return to his home country represented an absolutely fundamental challenge to the official Communist version of life in the People’s Republic. According to this official picture, the socialist system was the best of all possible worlds, every material and spiritual problem had been solved, and the church represented the old, backward order, a pack of superstitions and obscurantism, that enlightened Communist rule had long since rendered irrelevant. Intellectuals did not need religion because they were too smart for it; workers did not need it because they already lived in a workers’ paradise. This was the image reinforced at every stage, from cradle to grave, by all the official institutions of the Communist state.

…

He began his political career in 1963 by deriding the vote for women but extended the franchise to them during the revolution, when they had proved themselves avid supporters of the cause. For that matter, the phrase Islamic republic does not occur in his famous book Islamic Government. He once famously described Islam as a “religio-political faith.”5 To describe the government established by the Iranian Revolution of 1979 as a reversion to medieval obscurantism is to miss many of its essential characteristics. As one historian has noted, the revolution drew its force both from the long-established institutions of the Shia clergy and from the rise of the centralized twentieth-century state; both factors are crucial to our understanding of the house that Khomeini built.6 Scholar Ervand Abrahamian notes Khomeini’s remarkable capacity for moving outside the limits of received religious wisdom.

Geek Sublime: The Beauty of Code, the Code of Beauty

by

Vikram Chandra

Published 7 Nov 2013

And of course nobody ever told us about Tantric Sanskrit, or Buddhist Sanskrit, or Jain Sanskrit. By the beginning of the second millennium CE, Sanskrit had “long ceased to be a Brahmanical preserve,” but it was always presented to us as the great language of the Vedas.9 Sanskrit—as it was taught in the classroom—smelled to me of hypocrisy, of religious obscurantism, of the khaki-knickered obsessions of the Hindu far-Right, and worst, of an oppression that went back thousands of years. As far as I knew, in all its centuries, Sanskrit had been a language available only to the “twice-born” of the caste system, and was therefore an inescapable aspect of orthodoxy.

Brief Peeks Beyond: Critical Essays on Metaphysics, Neuroscience, Free Will, Skepticism and Culture

by

Bernardo Kastrup

Published 28 May 2015

To try to escape the inescapable, magicians appeal to a kind of word dance that philosopher Galen Strawson called ‘looking-glassing’: to use the word ‘consciousness’ in such a way that, whatever one means by it, it isn’t what the word actually denotes.63 What could motivate this kind of semantic obscurantism? If we carefully deconstruct it, we find that what appears to be actually denied are just some of the face-value traits ordinarily attributed to consciousness, not consciousness itself. Consider this passage from a New Scientist article titled ‘The grand illusion: Why consciousness exists only when you look for it’: If consciousness seems to be a continuous stream of rich and detailed sights, sounds, feelings and thoughts, then I suggest this is the illusion.

The Story of Philosophy

by

Will Durant

Published 23 Jul 2012

“Christ has brought the kingdom of God nearer to earth; but he has been misunderstood; and in place of God’s kingdom the kingdom of the priest has been established among us.”35 Creed and ritual have again replaced the good life; and instead of men being bound together by religion, they are divided into a thousand sects; and all manner of “pious nonsense” is inculcated as “a sort of heavenly court service by means of which one may win through flattery the favor of the ruler of heaven.”36—Again, miracles cannot prove a religion, for we can never quite rely on the testimony which supports them; and prayer is useless if it aims at a suspension of the natural laws that hold for all experience. Finally, the nadir of perversion is reached when the church becomes an instrument in the hands of a reactionary government; when the clergy, whose function it is to console and guide a harassed humanity with religious faith and hope and charity, are made the tools of theological obscurantism and political oppression. The audacity of these conclusions lay in the fact that precisely this had happened in Prussia. Frederick the Great had died in 1786, and had been succeeded by Frederick William II, to whom the liberal policies of his predecessor seemed to smack unpatriotically of the French Enlightenment.

…

“Every man is to be respected as an absolute end in himself; and it is a crime against the dignity that belongs to him as a human being, to use him as a mere means for some external purpose.”49 This too is part and parcel of that categorical imperative without which religion is a hypocritical farce. Kant therefore calls for equality: not of ability, but of opportunity for the development and application of ability; he rejects all prerogatives of birth and class, and traces all hereditary privilege to some violent conquest in the past. In the midst of obscurantism and reaction and the union of all monarchial Europe to crush the Revolution, he takes his stand, despite his seventy years, for the new order, for the establishment of democracy and liberty everywhere. Never had old age so bravely spoken with the voice of youth. But he was exhausted now; he had run his race and fought his fight.

Suburban Nation

by

Andres Duany

,

Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk

and

Jeff Speck

Published 14 Sep 2010

Jeff was the purveyor of the light touch. His easygoing tone has contributed as much as anything to the book’s appeal. It is probably responsible for the number of people who have told me that, to their own surprise, they read it to the end. Lizz, for her part, was the guardian of clarity. She has no patience for obscurantism in language or message. Suburban Nation’s simple and straightforward writing is an extension of the educational philosophy she promotes at the University of Miami, where students learn “plain old good architecture.” Her success is evidenced by the book’s unexpected popularity as required reading—even in high schools.

Bobos in Paradise: The New Upper Class and How They Got There

by

David Brooks

Published 1 Jan 2000

In 1995 George Gilder wrote, “Bohemian values have come to prevail over bourgeois virtue in sexual morals and family roles, arts and letters, bureaucracies and universities, popular culture and public life. As a result, culture and family life are widely in chaos, cities seethe with venereal plagues, schools and colleges fall to obscurantism and propaganda, the courts are a carnival of pettifoggery.” In 1996 Robert Bork’s bestseller, Slouching Towards Gomorrah, argued that the forces of the sixties have spread cultural rot across mainstream America. In 1999 William Bennett argued, “Our culture celebrates self-gratification, the crossing of all moral barriers, and now the breaking of all social taboos.”

The Great Tax Robbery: How Britain Became a Tax Haven for Fat Cats and Big Business

by

Richard Brooks

Published 2 Jan 2014

As luck would have it, the 2008 Finance Bill wending its way through parliament outlawed these arrangements, one Treasury minister calling them ‘highly artificial tax avoidance schemes’.32 Whatever Tesco’s protestations, there could be little doubt that – as the Guardian had alleged, albeit for the wrong reasons and not on the scale claimed – it was a corporate tax avoider.33 High farce ensued, as Tesco sought to exclude Private Eye’s revelations from the simmering libel action. In the High Court that summer the company’s expensive silk Adrienne Page QC pleaded to a bemused libel judge that ‘planning or efficiency that results in tax being avoided’ doesn’t make a company a ‘tax avoider as a slur’. Adopting the tax industry’s trademark obscurantism, she insisted: ‘It is now more usual to divide “tax avoidance” into aggressive and non-aggressive tax planning behaviour. The claimant [Tesco] would readily put itself into the second category, but not the first.’ Mr Justice Eady, who had spent the previous week getting to grips with more fathomable questions posed by Max Mosley’s sadomasochism parties, looked puzzled.

Live Work Work Work Die: A Journey Into the Savage Heart of Silicon Valley

by

Corey Pein

Published 23 Apr 2018

Therein lay the genius of Lawrence’s delightfully coy elevator pitch: What investor could refuse the chance to back a game that was just like Angry Birds, but new and different? Having pledged confidentiality, I can say little more regarding Lawrence’s stealth app. However, I will disclose that it involved tapping on pot leaves that, for sundry reasons including Apple’s App Store guidelines and impish stoner obscurantism, were not obviously pot leaves. There were at least two solid reasons for Lawrence’s paranoia. One was weed. The other was experience. People at startup events sometimes stole ideas, he said. And he had personally witnessed the secrecy with which the most prosperous tech companies treated their intellectual property.

The True and Only Heaven: Progress and Its Critics

by

Christopher Lasch

Published 16 Sep 1991

"Were a sovereign to incapacitate his subjects ... for obeying his laws, and then to torture them in dungeons of perpetual woe, we should say, that history records no darker crime." But when challenged to explain how the same injustice became just when attributed to God, Edwards's followers took refuge in obscurantism. Human beings, they said, must not sit in judgment of God. Why not?—Channing wanted to know. God's attributes were perfectly "intelligible," his justice the same as his creatures'. Human conceptions of right and wrong, though "learned from our nature" (the only source from which they could possibly be learned), were quite adequate to the job of judging God: and the God of Jonathan Edwards, Samuel Hopkins, and Joseph Bellamy stood convicted of high crimes and misdemeanors.

…

The uneasy coexistence of ethical individualism and medical collectivism grew out of the separation of sex from procreation, which made sex a matter of private choice while leaving open the possibility that procreation and child rearing might be subjected to stringent public controls. The objection that sex and procreation cannot be severed without losing sight of the mystery surrounding both struck liberals as the worst kind of theological obscurantism. For opponents of abortion, on the other hand, "God is the creator of life, and ... sexual activity should be open to that.... The contraceptive mentality denies his will, 'It's my will, not your will.' " If the abortion debate confined itself to the question of just when an embryo becomes a person, it would be hard to understand why it elicits such passionate emotions or why it has become the object of political attention seemingly disproportionate to its intrinsic importance.

World Economy Since the Wars: A Personal View

by

John Kenneth Galbraith

Published 14 May 1994

On Security and Survival IN OUR SOCIETY, the increased production of goods—privately produced goods—is, as we have seen, a basic measure of social achievement. This is partly the result of the great continuity of ideas which links the present with a world in which production indeed meant life. Partly, it is a matter of vested interest. Partly, it is a product of the elaborate obscurantism of the modern theory of consumer need. And partly, we have seen, the preoccupation with production is forced quite genuinely upon us by the tight nexus between production and economic security. However, it is a reasonable assumption that most people pressed to explain our concern for production—a pressure that is not often exerted—would be content to suggest that it serves the happiness of most men and women.

The Post-American World: Release 2.0

by

Fareed Zakaria

Published 1 Jan 2008

Paul Kennedy argues, “The sheer rigidity of Hindu religious taboos militated against modernization: rodents and insects could not be killed, so vast amounts of foodstuffs were lost; social mores about handling refuse and excreta led to permanently insanitary conditions, a breeding ground for bubonic plagues; the caste system throttled initiative, instilled ritual, and restricted the market; and the influence wielded over Indian local rulers by the Brahman priests meant that this obscurantism was effective at the highest level.”8 J. M. Roberts makes a broader point about the Hindu worldview, observing that it was “a vision of endless cycles of creation and reabsorption into the divine [which led] to passivity and skepticism about the value of practical action.”9 But if culture is everything, how to account for China and India now?

The Ecotechnic Future: Envisioning a Post-Peak World

by

John Michael Greer

Published 30 Sep 2009

It bears remembering that in the nineteenth century, for example, opera counted as a popular entertainment medium and women of privileged classes practiced the same handicrafts as their poorer sisters. Nowadays very few such common factors connect, say, the upper middle classes of an East Coast suburb with the rural poor of a Midwestern farm state. Folk cultures have guttered out or survive only as museum pieces, while elite culture withdraws behind walls of obscurantism — compare the accessible and popular fine art of the late nineteenth century with the unwelcoming and often offensive product served up by today’s art scene. the twilight of culture In a world lurching through economic crisis and the first wave of impacts from peak oil, it’s easy to dismiss this implosion of culture as a minor issue, but such a dismissal is as much a symptom of cultural collapse as anything cited already.

Pale Blue Dot: A Vision of the Human Future in Space

by

Carl Sagan

Published 8 Sep 1997

In a 1992 speech Pope John Paul II argued, From the beginning of the Age of Enlightenment down to our own day, the Galileo case has been a sort of "myth" in which the image fabricated out of the events is quite far removed from reality. In this perspective, the Galileo case was a symbol of the Catholic Church's supposed rejection of scientific progress, or of "dogmatic" obscurantism opposed to the free search for truth. But surely the Holy Inquisition ushering the elderly and infirm Galileo in to inspect the instruments of torture in the dungeons of the Church not only admits but requires just such an interpretation. This was not mere scientific caution and restraint, a reluctance to shift a paradigm until compelling evidence, such as the annual parallax, was available.

Immortality: The Quest to Live Forever and How It Drives Civilization

by

Stephen Cave

Published 2 Apr 2012

But first we will look at what led Mary Shelley and her companions to believe that science was on the verge of claiming control over life and death, and how this belief has shaped our world. AS Mary Shelley was penning Frankenstein, science was beginning to establish itself as the new authority on nature’s laws. In the preceding century, the scientific method of careful observation and experimentation had fully emerged from the obscurantism of the alchemists. Secret meetings had given way to public scientific societies, and coded tomes to published journals. But although the methods had changed, the aims remained the same: the mastery of nature and conquest of mortality. In her novel, Mary Shelley has the career of her young scientist hero, Victor Frankenstein, reflect these developments: he first dabbles with alchemy and the search for an elixir of life before being convinced instead of the power of physics and chemistry.

The Globalization Paradox: Democracy and the Future of the World Economy

by

Dani Rodrik

Published 23 Dec 2010

We get free trade—or something approximating it—only when the stars are lined up just right and the interests behind free trade have the upper hand both politically and intellectually. But why should this be so? Doesn’t free trade make us all better off—over the long run? If free trade is so difficult to achieve, is that because of narrow self-interest, obscurantism, political failure, or all of these combined? It would be easy to associate free trade always with economic and political progress and protectionism with backwardness and decline. It would also be misleading, as we saw in the previous chapter. The real case for trade is subtle and therefore depends heavily on context.

Language and Mind

by

Noam Chomsky

Published 1 Jan 1968

But the issue is academic, since, for the moment, there is no reason to suppose the assumption to be true. Goodman’s argument is a bit like a “demonstration” that there is no problem in accounting for the development of complex organs, because everyone knows that mitosis takes place. This seems to me to be obscurantism, which can be maintained only so long as one fails to come to grips with the actual facts. There is, furthermore, a non sequitur in Goodman’s discussion of first- and second-language acquisition. Recall that he explains the presumed ease of second-language acquisition on the grounds that it is possible to use the first language for explanation and instruction.

The Coming of Neo-Feudalism: A Warning to the Global Middle Class

by

Joel Kotkin

Published 11 May 2020

Those people are often excommunicated.”41 According to recent studies of cognitive behavior, the products of today’s universities are inclined to maintain rigid positions on various issues, confident of their own superior intelligence and perspicuity, and to be intolerant of other views. For example, the Atlantic found less tolerance for differing opinions in the Boston area, and other places with a high proportion of university graduates, than in less-educated regions.42 An Age of “Mass Amnesia” Universities can get away with obscurantism and enforced ideological conformism because of their enormous power over labor markets. They are no longer primarily about learning, as Jane Jacobs noted, but about providing the credential needed for a high-paying job.43 One recent study of American college students found that more than one-third “did not demonstrate any significant improvement in learning” in four years of college.44 Employers report that recent graduates are short on critical thinking skills.45 Equally worrying is that students in the West are not acquiring familiarity with their own cultural heritage.

A Devil's Chaplain: Selected Writings

by

Richard Dawkins

Published 1 Jan 2004

Nowadays some up-market newspapers, including the Telegraph, have dumbed down to the extent of printing a regular astrology column, which is why I accepted their invitation to write Crystalline Truth and Crystal Balls (1.6). A more intellectual species of charlatan is the target of the next essay, Postmodernism Disrobed (1.7). Dawkins’ Law of the Conservation of Difficulty states that obscurantism in an academic subject expands to fill the vacuum of its intrinsic simplicity. Physics is a genuinely difficult and profound subject, so physicists need to – and do – work hard to make their language as simple as possible (‘but no simpler,’ rightly insisted Einstein). Other academics – some would point the finger at continental schools of literary criticism and social science – suffer from what Peter Medawar (I think) called Physics Envy.

Structures: Or Why Things Don't Fall Down

by

J. E. Gordon

Published 1 Jan 1978

It called for a quite exceptional combination of imagination with intellectual discipline at a time when the very vocabulary of science barely existed. As it turned out, the old craftsmen never accepted the challenge, and it is interesting to reflect that the effective beginnings of the serious study of structures may be said to be due to the persecution and obscurantism of the Inquisition. In 1633, Galileo (1564–1642) fell foul of the Church on account of his revolutionary astronomical discoveries, which were considered to threaten the very bases of religious and civil authority. He was most firmly headed off astronomy and, after his famous recantation,* he was perhaps lucky to be allowed to retire to his villa at Arcetri, near Florence.

The Moral Landscape: How Science Can Determine Human Values

by

Sam Harris

Published 5 Oct 2010

It is one thing to be told that the pope is a peerless champion of reason and that his opposition to embryonic stem-cell research is both morally principled and completely uncontaminated by religious dogmatism; it is quite another to be told this by a Stanford physician who sits on the President’s Council on Bioethics.28 Over the course of the conference, I had the pleasure of hearing that Hitler, Stalin, and Mao were examples of secular reason run amok, that the Islamic doctrines of martyrdom and jihad are not the cause of Islamic terrorism, that people can never be argued out of their beliefs because we live in an irrational world, that science has made no important contributions to our ethical lives (and cannot), and that it is not the job of scientists to undermine ancient mythologies and, thereby, “take away people’s hope”—all from atheist scientists who, while insisting on their own skeptical hardheadedness, were equally adamant that there was something feckless and foolhardy, even indecent, about criticizing religious belief. There were several moments during our panel discussions that brought to mind the final scene of Invasion of the Body Snatchers: people who looked like scientists, had published as scientists, and would soon be returning to their labs, nevertheless gave voice to the alien hiss of religious obscurantism at the slightest prodding. I had previously imagined that the front lines in our culture wars were to be found at the entrance to a megachurch. I now realized that we have considerable work to do in a nearer trench. I have made the case elsewhere that religion and science are in a zero-sum conflict with respect to facts.29 Here, I have begun to argue that the division between facts and values is intellectually unsustainable, especially from the perspective of neuroscience.

Adriatic: A Concert of Civilizations at the End of the Modern Age

by

Robert D. Kaplan

Published 11 Apr 2022

Thus, I have always believed that journalism is invigorated by a return to terrain, to the kind of firsthand, solitary discovery of a place best associated with old-fashioned travel writing. Travel writing has always meant much more to me than what appears in the Sunday supplements: rather, it can be a deft vehicle for rescuing geography and geopolitics from the jargon and obscurantism of academia at its worst. I recall Winston Churchill’s The River War (1899) and T. E. Lawrence’s Seven Pillars of Wisdom (1926), which employ the experience of travel to explore geography, warfare, and statecraft in late-nineteenth-century Sudan and early-twentieth-century Arabia. Owen Lattimore’s The Desert Road to Turkestan (1929), another book that comes to mind, is about both the organization of camel caravans and Russian and Chinese imperial ambitions.

Democracy Incorporated

by

Sheldon S. Wolin

Published 7 Apr 2008

In varying degrees they advocated a politics centered on the middle class and excluding the working class and poor. None were egalitarians—with the possible exception of Bentham. They pitted intellectual elitism against the inherited privileges of an aristocracy, the free market against mercantilist notions of state control of the economy, and they sided with modern science against religious obscurantism. They were only moderately enthusiastic for political participation, favoring, instead, a larger role for disinterested public servants. Except for Adam Smith, whose Wealth of Nations appeared in 1776, the English version of liberalism was formulated roughly a quarter century after the American Revolution; hence it was not their liberalism that initially took hold in America.13 When the American colonists protested the taxes and import duties that the mother country had imposed, their arguments were primarily based on political principles concerning representation, not on economic theories.

The Mind in the Cave: Consciousness and the Origins of Art

by

David Lewis-Williams

Published 16 Apr 2004

But science should progress by incorporating past evidence into the new and not rejecting it.75 In the structuralist wake came an anti-theoretical age of agnostic empiricism.76 Researchers did not abandon structuralism for another theoretical perspective that would make better sense of the data: on the contrary, they abandoned theory altogether. Or, at least, so they believed. But it has not been entirely a Dark Age of obscurantism. Some researchers, such as Georges Sauvet, 77 Denis Vialou78 and Federico Bernaldo de Quirós, 79 have usefully pursued structuralist explanations. For Sauvet, a pattern is discernible in formal analysis of signs; for Vialou, it is in the distribution of species in specific panels. Bernaldo de Quirós sees Altamira as a planned structure comprising three principal sections, or nuclei, linked by passages: ‘Indeed, the decoration of the cave seems to conform to a pattern that invariably takes advantage of the natural relief, as do the masks in the Horse’s Tail, the doe’s head in the Pit, and the figures of bison on the Great Panel’.80 He believes that the sections of the cave were designed as a location for initiation rites.81 Structure is thus implicated in the reproduction of social order through initiation rites.82 Whether Sauvet, Vialou and Bernaldo de Quirós are correct in the specific patterns that they believe they have uncovered, the important point is that they continue to argue that there must be some pattern.

Giving the Devil His Due: Reflections of a Scientific Humanist

by

Michael Shermer

Published 8 Apr 2020

Griffith-Thomas: “It commences with the conviction of the mind based on adequate evidence; it continues in the confidence of the heart or emotions based on conviction, and it is crowned in the consent of the will, by means of which the conviction and confidence are expressed in conduct.” Such a definition – which McGrath describes as “typical of any Christian writer” – is what Dawkins, in reference to French postmodernists, calls “continental obscurantism.” Most of it describes the psychology of belief. The only clause of relevance to a scientist is “adequate evidence,” which raises the follow-up question, “Is there?” Dawkins’ answer is an unequivocal No. * * * Does a scientific and evolutionary worldview such as that proffered by Richard Dawkins obviate a sense of spirituality?

What We Owe the Future: A Million-Year View

by

William MacAskill

Published 31 Aug 2022

In 2002, when talking about the lack of evidence of Iraqi weapons of mass destruction, US Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld declared, “There are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns—the ones we don’t know we don’t know.”7 Rumsfeld’s comment was lampooned as obscurantism at the time, and it even earned a Foot in Mouth Award, which the Plain English Campaign bestows each year for “a baffling comment by a public figure.”8 But he was actually making an important philosophical point: we should bear in mind there may be considerations that we aren’t even aware of. To illustrate, suppose that a highly educated person in the year 1500 tried to make the longterm future go well.

The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers: Economic Change and Military Conflict From 1500 to 2000

by

Paul Kennedy

Published 15 Jan 1989

Economic notions remained primitive: imports of western wares were desired, but exports were forbidden; the guilds were supported in their efforts to check innovation and the rise of “capitalist” producers; religious criticism of traders intensified. Contemptuous of European ideas and practices, the Turks declined to adopt newer methods for containing plagues; consequently, their populations suffered more from severe epidemics. In one truly amazing fit of obscurantism, a force of janissaries destroyed a state observatory in 1580, alleging that it had caused a plague.10 The armed services had become, indeed, a bastion of conservatism. Despite noting, and occasionally suffering from, the newer weaponry of European forces, the janissaries were slow to modernize themselves.

…

The sheer rigidity of Hindu religious taboos militated against modernization: rodents and insects could not be killed, so vast amounts of foodstuffs were lost; social mores about handling refuse and excreta led to permanently insanitary conditions, a breeding ground for bubonic plagues; the caste system throttled initiative, instilled ritual, and restricted the market; and the influence wielded over Indian local rulers by the Brahman priests meant that this obscurantism was effective at the highest level. Here were social checks of the deepest sort to any attempts at radical change. Small wonder that later many Britons, having first plundered and then tried to govern India in accordance with Utilitarian principles, finally left with the feeling that the country was still a mystery to them.11 But the Mogul rule could scarcely be compared with administration by the Indian Civil Service.

God Is Back: How the Global Revival of Faith Is Changing the World

by

John Micklethwait

and

Adrian Wooldridge

Published 31 Mar 2009

Every Enlightenment thinker had his favorite example of Christianity’s blood-soaked past: Voltaire claimed that he awoke from his sleep in a sweat every year on the anniversary of the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre. The second foundation was confidence in human goodness. The rejection of original sin has been described as the “key that secularizes the world.”7 It set men fighting against obscurantism in thought and repression in government. It transformed education from rooting out evil in God’s garden to tending to young shoots. And it freed people to pursue real virtues such as human sympathy rather than false ones such as saintly self-mortification. (“A gloomy, hare-brained enthusiast, after his death, may have a place in a calendar,” David Hume scoffed, “but [he] will scarcely ever be admitted, when alive, into intimacy and society, except by those who are as delirious and dismal as himself.”8) This was a key that the philosophes turned whenever they could.

A Dominant Character

by

Samanth Subramanian

Published 27 Apr 2020

AT THE 1948 CONFERENCE, in the House of Scientists on Prechistenka Street, academicians fell into line with alacrity. Biologist after biologist applauded Lysenko and the new Soviet genetics and then hurried on to demonstrate how their own research conformed to these radical principles. One scientist called classical genetics “a pseudo-science,” another a “propaganda of obscurantism.” (“Hear, hear!” an audience member yelled.) For a while, these supporters of Lysenko dominated the proceedings. “Why has no one of the adherents of formal genetics taken the floor?” a needling note, passed up to the conference chair midway through the first day, wondered. “Is it because they do not want to speak themselves, or because they are not being given a chance to speak?”

The Sinner and the Saint: Dostoevsky and the Gentleman Murderer Who Inspired a Masterpiece

by

Kevin Birmingham

Published 16 Nov 2021

It knew how many landowners were murdered each year, and it responded with symbolic measures, like forcing landowners to whip their serfs with the cat-o’-three-tails instead of the knout. “Proponent of the knout,” Dostoevsky read, declaiming to the absent Gogol, “apostle of ignorance, champion of obscurantism and Stygian darkness, panegyrist of Tatar morals—what are you about! Look beneath your feet—you are standing on the brink of an abyss!” Gogol’s tsarism was a betrayal because Russians had begun to think of writers as more than writers. “You do not properly understand the Russian public,” Dostoevsky read to the assembled Petrashevists.

On Language: Chomsky's Classic Works Language and Responsibility and Reflections on Language in One Volume

by

Noam Chomsky

and

Mitsou Ronat

Published 26 Jul 2011

Locke’s epistemology, as John Yolton shows, was developed primarily for application to religious and moral debates of the period; “the vital issue between Locke and his critics [on the doctrine of innateness] was the grounds and foundations of morality and religion” (Yolton, 1956, p. 68). Throughout the modern period, not to speak of earlier eras, such questions lie in the background of seemingly arcane philosophical controversies and often help explain their issue. Classical British empiricism arose in often healthy opposition to religious obscurantism and reactionary ideology. Its appeal, perhaps, resides in part in the belief that it offers a vision of limitless progress in contrast to the pessimistic doctrine that humans are enslaved by an unchangeable nature that condemns them to intellectual servitude, material deficit, and eternally fixed oppressive institutions.

Scots and Catalans: Union and Disunion

by

J. H. Elliott

Published 20 Aug 2018

It was an interpretation that resonated strongly with the Carlists, who would deploy it in the defence of a politically reactionary romantic regionalism against the centralizing aspirations of the state. 128 While the Catalan bourgeoisie was deeply devout, and the Renaixença was suffused with religious sentiment, growing clerical obscurantism in the 1850s and 1860s, together with the association of a discredited monarchy with the forces of conservative reaction, progressively alienated the more liberal sections of Catalan society. Many members of the Catalan bourgeoisie held to the top-down narrative of the creation of Spain as a unitary nation-state elaborated by successive Liberal regimes.

The Rise and Fall of Modern Medicine

by

M. D. James le Fanu M. D.

Published 1 Jan 1999

When a medical academic’s ‘commercial involvement reaches this level’, observes the disapproving editor of The Lancet, ‘the very independence of research and opinion is put at risk’.7 This unhealthy situation is the inevitable reverse side of the dynamic and progressive nature of the pharmaceutical industry that was so intrinsic to the Rise, for, self-evidently, the drug companies as capitalist enterprises cannot escape from the imperative to innovate, they cannot impose restraints upon themselves, and thus must pursue every legitimate avenue in promoting the drugs up to, and including, subverting the integrity of the medical profession. It is possible from these reflections on medicine and progress to make a very clear distinction. Genuine progress, optimistic and forward-looking, is always to be welcomed, but progress as an ideological necessity leads to obscurantism, falsehood and corruption. The question of how to maximise the possibilities of the former while rejecting the latter is best resolved by accepting at face value the version of events as revealed by this historical account, where the last fifty years are best seen as one episode, albeit a very glorious one (indeed a culminating one), in an historical tradition that stretches back over the past 2,500 years.

Ghosts of Empire: Britain's Legacies in the Modern World

by

Kwasi Kwarteng

Published 14 Aug 2011

The unorthodox methods of these district commissioners in the south by the end of the 1930s often led to administrative chaos.9 The Bog Barons supported the ‘Southern Policy’, because it protected their power and independence from officials in the north, and many of them were believers in the system of ‘indirect rule’, of building up self-contained ethnic or tribal units in the south of the country, which could then be used as bulwarks against the encroachments of Islam and Arab culture. Robertson, appointed civil secretary in 1945, did not share these views. He disliked what he felt to be the obscurantism and eccentricity of the southern district commissioners, and believed that the southern Sudan had to be ‘opened up and brought into touch with reality’.10 The nature of this ‘reality’ was probably as unclear to Sir James as to everyone else. He certainly misjudged, as did so many others, the pace of change in the colonial empire and the speed with which parts of it were hurrying along the path to independence.

The Library: A Fragile History

by

Arthur Der Weduwen

and

Andrew Pettegree

Published 14 Oct 2021

He answered that the monks, seeking to gain a few soldi, were in the habit of cutting off sheets and making psalters.1 As with Hugo Blotius’s description of his arrival in the Hofbibliothek, we may suspect an element of exaggeration in this account of Boccaccio’s visit. Just as the emperor’s new librarian was keen to play up his own great achievement in reordering the library, so too the humanist scholars of the Renaissance were eager to contrast their own bold new intellectual agenda with the obscurantism of the established medieval institutions. This somewhat mean-spirited account, written during the 1370s, does little credit to the fortitude of the monks of Monte Cassino, whose home had recently been devastated by an earthquake. Many of the monks had been expelled, replaced by a garrison of soldiers fulfilling their part in the political game of chess played by the Pope and the crowns of France and Aragon for control of southern Italy.

Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed

by

James C. Scott

Published 8 Feb 1999

The ship moves independently with its own enormous motion, the boat hook no longer reaches the moving vessel, and suddenly the administrator, instead of appearing a ruler and a source of power, becomes an insignificant, useless, feeble man. -Leo Tolstoy, War and Peace The conflict between the officials and specialists actively planning the future on one hand and the peasantry on the other has been billed by the first group as a struggle between progress and obscurantism, rationality and superstition, science and religion. Yet it is apparent from the high-modernist schemes we have examined that the "rational" plans they imposed were often spectacular failures. As units of production, as human communities, or as a means of delivering services, the planned villages failed the people they were intended, sometimes sincerely, to serve.

Never Let a Serious Crisis Go to Waste: How Neoliberalism Survived the Financial Meltdown

by

Philip Mirowski

Published 24 Jun 2013

It may sometimes feel that a certain market-inflected personalized version of Salvation has become more prevalent in Western societies, but that turns out to be very far removed from the actual content of the neoliberal program. Neoliberalism does not impart a dose of that Old Time Religion. Not only is there no ur-text of neoliberalism; the neoliberals have not themselves opted to retreat into obscurantism, however much it may seem that some of their fellow travelers may have done so. You won’t often catch them wondering, “What Would Hayek Do?” Instead they developed an intricately linked set of overlapping propositions over time—for example, from Ludwig Erhard’s “social market economy” to Herbert Giersch’s cosmopolitan individualism, from Milton Friedman’s “monetarism” to the rational-expectations hypothesis, from Hayek’s “spontaneous order” to James Buchanan’s constitutional order, from Gary Becker’s “human capital” to Steven Levitt’s “freakonomics,” from Heartland’s climate denialism to AEI’s geoengineering project, and, most appositely, from Hayek’s “socialist calculation controversy” to Chicago’s efficient-markets hypothesis.

Britain at Bay: The Epic Story of the Second World War: 1938-1941

by

Alan Allport

Published 2 Sep 2020

The Conservatives won two-thirds of Scotland’s constituencies in the 1931 election. Labour dominated in Wales, but neither Welsh nor Scottish socialists had any time for parochial identity politics; they saw the future in strictly British terms. Plaid Cymru and the Scottish National Party between the wars became absorbed with medieval obscurantism and an unhealthy taste for continental fascism, neither of which was calculated to impress the sober middle classes of Cardiff or Edinburgh.23 In any case, the terrible slaughter of the First World War had bequeathed a legacy of shared sacrifice that Britons from all parts of the UK could embrace as a unitary tragedy.

Unelected Power: The Quest for Legitimacy in Central Banking and the Regulatory State

by

Paul Tucker

Published 21 Apr 2018

Monarch of the City of London, guardian of the international gold standard, enforcer of domestic budgetary discipline, his powers, but not his office, were stripped away in the early 1930s. Born in 1871 and formed in the world left behind by World War I, Norman’s mistake was not to grasp the profoundly changed expectations of public policy brought about by full-franchise democracy: recessions mattered, and opacity bordering on obscurantism was alienating unless policy was magnificently effective. Even had he wanted to be a legitimacy seeker, he had lost his bearings. A man desperately devoted to trying to do the right thing, he is a reminder that, where legitimacy is fragile and jealousies about relative power abound, costly mistakes—contributing to crises—can prompt profound institutional reform.

Wasps: The Splendors and Miseries of an American Aristocracy

by

Michael Knox Beran

Published 2 Aug 2021

If, during Holy Week at Roissy in 1659, the Abbé Le Camus did not actually christen a pig and say a Black Mass over it, “scandalizing a court not scrupulous,” the story is suggestive of the animus that the luminary is likely feel in the face of a deeper, because more lyric and poetic, reasonableness. VIII. The thought has something in common with Santayana’s intuition that religious wisdom may be literally false but morally true. Not a noble lie, but an acknowledgment of the truth of a deeper mystery. To concede that we are continuously touched by mystery is not obscurantism, it is sanity. Without mystery we should die of boredom. About the Author MICHAEL KNOX BERAN is a lawyer and the author of several books, among them The Last Patrician, a study of Robert Kennedy that was a New York Times Notable Book of the Year and Murder By Candlelight, a New York Times Editor’s Choice.

Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress

by

Steven Pinker

Published 13 Feb 2018

Diagnoses of the malaise of the humanities rightly point to anti-intellectual trends in our culture and to the commercialization of universities. But an honest appraisal would have to acknowledge that some of the damage is self-inflicted. The humanities have yet to recover from the disaster of postmodernism, with its defiant obscurantism, self-refuting relativism, and suffocating political correctness. Many of its luminaries—Nietzsche, Heidegger, Foucault, Lacan, Derrida, the Critical Theorists—are morose cultural pessimists who declare that modernity is odious, all statements are paradoxical, works of art are tools of oppression, liberal democracy is the same as fascism, and Western civilization is circling the drain.54 With such a cheery view of the world, it’s not surprising that the humanities often have trouble defining a progressive agenda for their own enterprise.

A History of the Bible: The Story of the World's Most Influential Book

by

John Barton

Published 3 Jun 2019

By this means Torah comes out on top, and the tradition of wisdom, going back so far, is to some extent seen as surpassed by the specifically Israelite tradition of Torah: ‘the author is claiming for the Jewish law a universal significance, and in so doing he no doubt is also concerned to answer charges of intellectual obscurantism and xenophobia directed at Jewish religious thought and practice which were in the air at that time.’23 Non-Jews in the Persian and subsequent periods often regarded Jews with suspicion, particularly because they did not revere the gods as ‘normal’ people did, but insisted on their own, single God to the exclusion of all others.

Europe: A History

by

Norman Davies

Published 1 Jan 1996

Renaissance scholars began to talk in the fifteenth century of the ‘Middle Age’ as the interval between the decline of antiquity and the revival of classical culture in their own times. For them, the ancient world stood for high civilization; the Middle Age represented a descent into barbarism, parochiality, religious bigotry. During the Enlightenment, when the virtues of human reason were openly lauded over those of religious belief, ‘medievalism’ became synonymous with obscurantism and backwardness. Since then, of course, as the ‘Modern Age’ which followed the Middle Age was itself fading into the past, new terms had to be invented to mark the passage of time. The medieval period has been incorporated into the fourfold convention which divides European history into ancient, medieval, modern, and now contemporary sections.

…

The perpetual financial crisis, fuelled by recurrent wars, turned the clashes between court and Parlement into ? routine spectacle. The religious feuds between the ultramontanes, Gallicans, and Jansenists, which culminated in 1764 with the expulsion of the Jesuits, degenerated into a ritual round of spite and obscurantism. The chasm between court and people yawned ever wider. The most memorable personality of the age must surely be that of Jeanne Poisson, Mme de Pompadour (1721–64)—intelligent, influential, and totally helpless. She did what she could to relieve the King’s unspeakable boredom, and is credited with that most telling of remarks, ‘Après nous le déluge’, [CORSICA] [DESSEIN] Louis XVI no doubt looked forward to a reign as long and as boring as that of his grandfather.

In Europe

by

Geert Mak

Published 15 Sep 2004

The city's structure was just as ambiguous as all other facets of Viennese life. It did its utmost to generate awe for the emperor's power, and more than that: the layout of the city's streets actually formed a direct reflection of imperial order. At the same time, for many young Viennese, the Ring was the symbol of theatrical falsehood, a Potemkin project full of obscurantism and counterfeit history, the product of stage designers who wanted everyone to think that Vienna was populated only by nobility, and by no one else. Somewhere I saw a group portrait by the painter Theo Zasche, painted in 1908 and showing all of Vienna's prominent citizens on the Sirk corner of the Ring, the haunt of the elite across from the Opera – what the pamphleteer Karl Kraus called the ‘cosmic intersection’ of Vienna.

The House of Morgan: An American Banking Dynasty and the Rise of Modern Finance

by

Ron Chernow

Published 1 Jan 1990

At the same time, the partners were by no means hostile to all federal intervention to stop the Depression. If they hewed to the balanced-budget dogma and opposed higher taxes, Lamont, Leffingwell, and Parker Gilbert also advocated cheaper money to combat deflation. By contrast, the American Bankers Association attacked Roosevelt’s policy of low interest rates. The obscurantism of their fellow bankers sometimes bothered the Morgan men. “I sometimes wonder whether we ought to continue to give our silent sanction to the American Bankers Association by continuing our membership in it,” Leffingwell said, blaming tight Fed policy in 1936-37 for that year’s downturn.24 In modern parlance, the Morgan partners were sympathetic to macroeconomic management of the overall economy, even if they deplored microeconomic regulation of specific industries.

The Pursuit of Power: Europe, 1815-1914

by

Richard J. Evans

Published 31 Aug 2016

In 1875 the Prussian state ended subsidies to the Catholic Church; all religious orders were dissolved, and civil marriage was made compulsory. The flames of conflict were fanned by the German liberals, who cheered Bismarck on in what they came to call the ‘struggle of civilizations’, or Kulturkampf, pitting enlightened progressivism against reactionary obscurantism. The Catholic clergy would not bow to the new laws. They boycotted state training institutions, and refused to submit clerical appointments for government approval. The police moved in and by the mid-1870s some 989 Catholic parishes were without incumbents, 225 priests were in prison, two archbishops and three bishops had been removed from office, and the Bishop of Trier had died shortly after ending a nine-month jail sentence: the furore over the alleged apparitions at Marpingen occurred at the centre of this conflict.

A History of Western Philosophy

by

Aaron Finkel

Published 21 Mar 1945

On the whole, the school which owed its origin to Locke, and which preached enlightened self-interest, did more to increase human happiness, and less to increase human misery, than was done by the schools which despised it in the name of heroism and self-sacrifice. I do not forget the horrors of early industrialism, but these, after all, were mitigated within the system. And I set against them Russian serfdom, the evils of war and its aftermath of fear and hatred, and the inevitable obscurantism of those who attempt to preserve ancient systems when they have lost their vitality. CHAPTER XVI Berkeley GEORGE BERKELEY (1685-1753) is important in philosophy through his denial of the existence of matter—a denial which he supported by a number of ingenious arguments. He maintained that material objects only exist through being perceived.

The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power

by

Daniel Yergin

Published 23 Dec 2008

Moussadeq has got to be maintained to save Persia from Communism, they have got to choose between saving Persia and ruining this country." There was much frustrating argument within the British government over what to do and whom to blame—and also a great deal of impatience and anger with Anglo-Iranian and what seemed to officials to be its obscurantism. Eden himself complained that the company's chairman, Sir William Fraser, was "in cloud cuckoo land."[12] In the autumn of 1951, a few weeks after the departure of the British from Abadan, Mossadegh went to the United States, to plead the cause of Iran at the United Nations. He also went to Washington to make his case to Truman and Acheson and to ask for economic aid.

The Codebreakers: The Comprehensive History of Secret Communication From Ancient Times to the Internet

by

David Kahn

Published 1 Feb 1963

Involved is the Kabbalah-like computation of the numerical values of the angels’ names; Trithemius, like other hermeticists, regarded Moses as a kind of Jewish Hermes Trismesgistus. He showed the “Steganographia” in its incompleted state to a visitor, who was so horrified at its barbarous names of seraphim, its obscurantism, its impossible claims, that he denounced it as sorcery. A letter which Trithemius wrote to a friend arrived after the friend had died; the prior of the abbey opened it, was likewise shocked, and passed it around. Trithemius fell under a cloud of working in magic, which the church even then frowned upon.

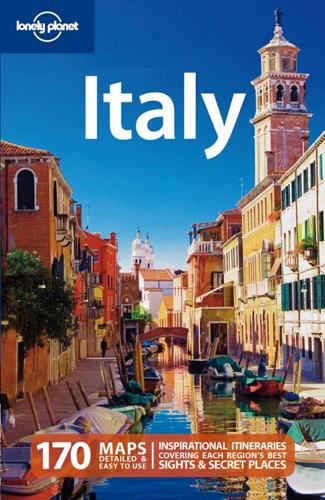

Italy

by

Damien Simonis

Published 31 Jul 2010