Why Your World Is About to Get a Whole Lot Smaller: Oil and the End of Globalization

by

Jeff Rubin

Published 19 May 2009

There is something bigger going on. OIL SHOCKS HAVE ALWAYS CAUSED RECESSION Here’s a clue. Soaring oil prices caused four of the last five global recessions. The only one that wasn’t caused by oil prices, the Asian meltdown of 1998, never even washed ashore in the major oil-consuming economies of the world like the United States and Western Europe. By contrast, two of the largest recessions in the postwar period came directly after the last two OPEC oil shocks. The second OPEC shock actually reverberated into two back-to-back recessions. A decade later, another oil shock, this time caused by Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait and subsequent torching of many of its oil wells, also produced a fairly deep recession in 1991.

…

Gasoline prices in the United States rose from around $1.80 per gallon in 2004 to over $4 per gallon in mid-2008, an increase that now dwarfs even the price hikes motorists had to contend with during the OPEC oil shocks. The run-up since 2002 is almost four times as great as the increase following the Iranian Revolution. Even in inflation-adjusted terms (or “constant dollars,” as economists call them), the price of gasoline climbed to levels greater than when cursing 1970s American motorists had to line up at gas stations due to fuel shortages. Suddenly, the OPEC oil shocks that had seemed like a worst-case scenario don’t look so bad. In fact, the process of having our world shrink promises to be much more wrenching this time around, if only because it has got so much bigger since the last energy crisis.

…

In Japan, where production lines are slowing and workers being sent home, sales are down 32 percent, to 35-year lows. German car sales are the worst since reunification—down 14 percent in January. Still, the US has been hit particularly hard. Sales in February fell by 41 percent compared to 2008. Oil shocks have always turned the rugged capitalists of Detroit into big-time Keynesians. Following the second OPEC oil shock, Lee Iacocca went begging to Washington to save Chrysler from bankruptcy. Then in 2008, taxpayers again heard Detroit’s all-too-familiar refrain, “Brother, can you spare a dime?” And Congress voted 370–58 to approve a $25 billion bailout package for the auto industry.

The Oil Kings: How the U.S., Iran, and Saudi Arabia Changed the Balance of Power in the Middle East

by

Andrew Scott Cooper

Published 8 Aug 2011

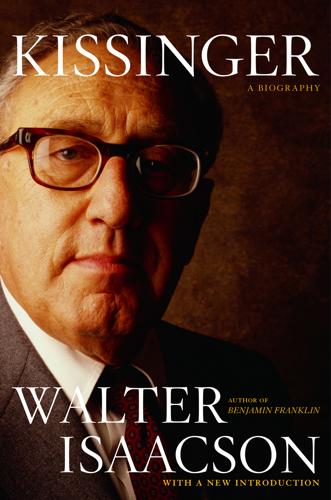

Kissinger’s remarks to Bhutto suggest that he feared a repeat of the anti-Shah disturbances of 1953 and 1963, that he now accepted that high oil prices posed as much a threat to the stability of Iran as they did to, say, Italy—to oil producers as well as oil consumers—and that friendly authoritarian dictatorships as well as Western democracies were in equal peril from the ructions of the oil shock. To Bhutto, Kissinger complained that the oil shock could have been avoided had the Nixon administration accepted the Shah’s offer in 1969 to buy millions of barrels of Iranian oil at a special discount. The deal promoted by Herbert Brownell had been judged illegal under U.S. law because it violated the quota laws that applied to petroleum imports.

…

E183.8.I55C66 2011 327.73055—dc22 011008319 ISBN 978-1-4391-5517-2 ISBN 978-1-4391-5713-8 (ebook) To My Family CONTENTS Introduction A Note on the Use of Iranian Imperial Titles PART ONE: GLADIATOR 1. A Kind of Super Man 2. Guardian of the Gulf 3. Marital Vows 4. Contingencies 5. Oil Shock 6. Cruel Summer PART TWO: SHOWDOWN 7. Screaming Eagle 8. Potomac Scheherazade 9. Henry’s Wars 10. The Spirit of ’76 11. Royal Flush 12. Oil War Epilogue: The Last Hurrah Acknowledgments Notes Bibliography Index INTRODUCTION “Why should I plant a tree whose bitter root Will only serve to nourish poisoned fruit?”

…

The narrative includes stories told for the first time, that, for example, illustrate the extraordinary degree of Iranian involvement—not to mention outright manipulation—in U.S. politics and foreign policy in the 1970s, and the extent to which the tentacles of the oil states of the Middle East reached right into the Oval Office to influence presidential decision making to an astonishing degree on domestic and foreign policy. We now know that the U.S. response to the 1971 India-Pakistan War, the 1972 U.S. presidential election, the Arab-Israeli War of 1973, the 1973–74 Arab oil embargo, the 1974–75 oil shock, the 1975 Middle East peace shuttle, and the 1976 U.S. presidential election all had an Iranian component. This book provides answers to long-standing questions about U.S.-Iran military contingency planning, the Ibex spy project, Iran’s nascent nuclear program, and the mysterious dealings of Colonel Richard Hallock.

MegaThreats: Ten Dangerous Trends That Imperil Our Future, and How to Survive Them

by

Nouriel Roubini

Published 17 Oct 2022

“To suggest that stagflation is a mystery merely indicates that one has elected to view the world through narrow econometric lenses rather than more widely through social and political as well as economic ones,” he wrote. “There is a problem here, but if there is a mystery, it is in the eye of the beholder, not in the real world.” By early 1979 the Islamic revolution in Iran led to a second oil shock, another oil embargo, another spike in oil prices, even higher inflation, and a return to outright stagflation. While fiscal and monetary policy had remained loose after the first oil shock, feeding the inflation rate, inflation nearly doubled to 13.3 percent in 1979. And then, finally, came the decisive intervention: besieged by critics, Carter chose inflation hawk Paul Volcker to head the Federal Reserve.

…

But ultimately, it was Paul Volcker’s crippling interest rates that brought inflation rates back down from their stratospheric heights. Reagan finally declared victory over stagflation in 1983. What ultimately explains the stagflation that the United States and other advanced economies experienced in the 1970s? The short answer: oil shocks together with a misguided policy response that released restraints on inflation expectations. Oil shocks, like all negative aggregate supply shocks, reduce potential growth and increase production costs. That puts pressure on companies that use oil; they must trim payrolls and/or raise prices. Loose monetary policy lowers the cost of capital, helping companies maintain payrolls until demand resumes.

…

If, however, the job loss is permanent and replacing my income is unlikely, for example, because of a health issue that impairs my productivity, then my lifestyle and spending must be adjusted to match my new circumstances. Otherwise, I’ll go bankrupt. The oil shocks were permanent—OPEC was a new force that would continue to act as a bloc, for the most part. That increased the real price of oil on a permanent basis and reduced the future growth of oil importing economies. That also raised the structural level of unemployment. The right policy response should have accepted those unpleasant facts. Tight monetary and fiscal policies, rather than loose ones, could have prevented runaway inflation. Had tighter monetary and fiscal policies prevailed, the oil shock would not have caused wages and prices to spiral across the board.

The Power Surge: Energy, Opportunity, and the Battle for America's Future

by

Michael Levi

Published 28 Apr 2013

In particular, as U.S. oil consumption shrinks, the U.S. economy will be a smaller piece of the oilprice puzzle; constraints on economic growth in places such as China and India in the face of expensive oil (and efforts by oil producers to keep prices at levels that those economies find manageable) may help restrain price increases before they really hurt the United States. There THE CAR OF THE FUTURE • 131 is good reason to believe that, this time, better oil efficiency will really pay off. Nevertheless, it’s possible to overstate the value of using less oil. Oil shocks typically precede recessions, but after forty years of careful studies economists still can’t agree on whether oil shocks actually cause big economic downturns. (One economist I know likes to quip that oil price spikes have preceded six of the last three recessions.) Even studies of the biggest oil spike of them all—the result of the 1973 Arab embargo—aren’t conclusive when it comes to how much of the ensuing recession should be pinned on oil.

…

Many of the details are novel, but the roots of the basic conflicts stretch back to the first modern oil crisis, which rocked the world in the autumn of 1973, and its aftermath. It is no exaggeration to claim that most of the battle lines defining today’s clashes were first drawn decades ago. The oil shock that struck on October 16, 1973, came at a time of enormous change and uncertainty for the United States. The Paris Peace Accords, signed in January of that year, had begun to end the Vietnam War, but Americans remained torn by the conflict. The Watergate scandal, which would eventually end Richard Nixon’s presidency, was slowly coming to light.

…

Two lasting changes that would help the United States over the next decade eventually emerged, though neither was without controversy.11 The first was the opening of the Trans-Alaskan Pipeline, a ten-billion-dollar, two-million-barrel-a-day behemoth running from Prudhoe Bay on the North Slope of Alaska to the Pacific port of Valdez. The pipeline had been on the table before the energy crisis but stalled in the face of hostility to its construction from environmental and Native American groups. The oil shock quickly broke down the opposition, and on November 16, 1973, Nixon signed broadly supported legislation moving the pipeline forward. By the end of the 1970s, it would allow previously landlocked oil to flow to the lower forty-eight states, reversing the earlier decline in U.S. crude production. American output bottomed out in 1976, and U.S. production would remain above its 1976 level until 1989.

The King of Oil: The Secret Lives of Marc Rich

by

Daniel Ammann

Published 12 Oct 2009

ISRAEL AND THE SHAH Top-Secret Pipeline in Israel • Trading with the Shah of Persia • Crude Middleman • Yom Kippur War • The Breaking Off 7. MARC RICH + COMPANY Swiss Secrecy • Vendetta • Thanks to Iranian Oil • The Oil Shock of 1974 • Faster, Longer, More Aggressive • The Invention of the Spot Market • The Secret of Trust • “Don’t Let Them Eat Your Soul” • Pioneer of Globalization 8. TRADING WITH THE AYATOLLAH KHOMEINI Khomeini’s Return • Iran Hostage Crisis • The Second Oil Shock of 1979 • “We Had Oil Available, and Our Competitors Did Not” • Israel’s Salvation 9. THE CASE Marc Who? • “With Our Shotguns Blazing” • Rich’s Flight to Switzerland • Rudolph W.

…

In these commodity trades, the risk was primarily carried by the bank that had extended the line of credit. Its collateral for the credit deal was the commodity at issue, in this case oil. The Oil Shock of 1974 It was a good time for a commodities trader who wanted to go into business for himself. The world had been changed forever by the Arab oil embargo—imposed in the wake of the Yom Kippur War—and skyrocketing oil prices. These developments led to the world’s first oil shock, a shock that would have serious economic consequences the world over. The price for a gallon of gasoline rose from 38.5 in May 1973 to 55.1 in June 1974.5 It was the first time since the Second World War that the United States had seen gasoline shortages.

…

The United States government offered a high reward for his capture and chased him all over the world. Rich’s is one of the most amazing careers of the twentieth century, a career that is tightly woven with great events in world history: Fidel Castro’s revolution in 1959; the decolonization of Africa in the 1960s; the Yom Kippur War and the oil shock of 1974; the fall of the shah of Persia and the seizure of power by the Ayatollah Khomeini in Iran in 1979; apartheid South Africa in the 1980s; and the crumbling of the Soviet Union in the 1990s. Marc Rich and his business partners were on the scene when these events happened. Thanks to their know-how, their hard work, and their considerable aggression, they were able to react to these events to their benefit more than their competitors ever could.

Crude Volatility: The History and the Future of Boom-Bust Oil Prices

by

Robert McNally

Published 17 Jan 2017

“Oil ‘Facts’ Don’t Quite Match the Rhetoric.” New York Times, March 18, 1979, E5. Hamilton, James. “Historical Causes of Postwar Oil Shocks and Recessions.” Energy Journal 6, no. 1 (1985): 97–116. ——. “Historical Oil Shocks.” February 1, 2011. http://econweb.ucsd.edu/~jhamilto/oil_history.pdf. ——. “Understanding Crude Oil Prices.” National Bureau of Economic Research, Working paper 14492, Cambridge, Mass., 2008. Hamilton, James D. Causes and Consequences of the Oil Shock of 2007–2008. San Diego, Calif.: UC San Diego, Department of Economics, 2009. Hammes, David, and Douglas Wills. Black Gold: The End of Bretton Woods and the Oil Price Shocks of the 1970s.

…

DeGolyer and MacNaughton, Twentieth Century Petroleum Statistics, 108. 151. Yergin, The Prize, 543–46. 152. Reserves (Federal Trade Commission. International Petroleum Cartel, Table 1, Table 8, 5–6, 23). 153. Data for 1950 (Federal Trade Commission. International Petroleum Cartel, Table 10, 25). 154. Hamilton, “Historical Causes of Postwar Oil Shocks,” 99; Hamilton, “Historical Oil Shocks,” 9. 155. Maugeri, 2006, 48. 156. “The Commission had the companies’ demand forecasts for the next month, and they also had excellent inventory data, with a lag of only about a week or two. When stocks appeared to be accumulating, production would be cut back. If inventories appeared to be falling below the amount needed to support current production, production quotas [quotas] would be increased.

…

A series of sabotage attacks, strikes, and commercial disputes in Venezuela, Iraq, Nigeria, the North Sea hit the market and contributed to the rapid increase in crude prices.67 For the first time ever, in February 2008, crude prices breached $100. As the summer of 2008 approached, they were hurtling over $140.68 The crude oil price shock between the fourth quarter of 2007 and second quarter of 2008—37 percent in real terms, 41 percent nominal, for U.S. imported crude oil prices—was “by any measure … one of the biggest oil shocks on record.”69 In the United States pump prices tracked those of crude to astounding new highs. In real terms, average national pump prices for regular grade gasoline exceeded their prior high set in March 1981 ($3.80 per gallon) in April of 2008 ($3.84) and then jumped up to peak at $4.43 in June.70 In nominal terms, pump prices peaked in July 2008 at $4.06 per gallon.

An Extraordinary Time: The End of the Postwar Boom and the Return of the Ordinary Economy

by

Marc Levinson

Published 31 Jul 2016

As cold weather arrived, truck drivers blocked highways to protest the soaring price of diesel fuel, and homeowners unplugged their Christmas lights in sympathy—or, perhaps, to avoid the opprobrium of their neighbors. Texas, a state floating on oil, gave birth to a popular bumper sticker urging, “Freeze a Yankee.” Gas lines, clogged with drivers desperate to top off nearly full tanks while the precious liquid was still available, symbolized the collapse of the American dream. The oil shock upset the equilibrium in Canada, setting off a boom in oil-rich Alberta while crippling import-dependent Quebec. The reverberations were even more disquieting in Japan. As petroleum prices rose through 1973, the Japanese did not anticipate serious trouble; their country had little engagement with the Middle East, and many Japanese companies had even complied with the Arab boycott against Israel.

…

After the embargo was announced, the British and French governments both predicted robust economic growth in 1974. As late as November 14, even though oil was now selling for $5.12 a barrel instead of $2.90, the Federal Reserve raised its forecast of US economic growth while lowering its forecast of unemployment.22 Only in late November, six weeks after the oil shock, did the reality sink in. In September, the Japanese economy had been so hot the government took special measures to slow it down; in November, the same officials slashed their forecast of economic growth for the coming months to zero. French economists warned that growth could plummet. At the Fed, the optimistic November 14 forecast was consigned to the dustbin.

…

Governments and central bankers knew, or thought they knew, how to use “traditional methods of economic management”—raising and lowering interest rates, taxes, and government spending—to restore an economy to health. When it came to fixing declining productivity growth, however, the economists’ toolbox was embarrassingly empty. CHAPTER 6 Gold Boys Sentiment at the start of 1973 had been buoyant. A year later, as the oil shock reverberated through the world economy, the atmosphere was vastly different. Inflation continued to rise. West Germany had just banned the importation of immigrant workers, on which its industries had relied since 1955, and Austria was about to follow. As “Help Wanted” signs were taken down across Northern and Central Europe, families in Turkey, Yugoslavia, Portugal, and Greece, which together supplied Germany with workers by the millions, began to feel the pain.

Capitalism 4.0: The Birth of a New Economy in the Aftermath of Crisis

by

Anatole Kaletsky

Published 22 Jun 2010

Second, and more important, the market price can and should be altered if good reasons exist to do this—whether these reasons reflect political objectives, such as the desire to reduce oil revenues available to Middle Eastern terrorists, or economic ones, such as the desire to avoid another recession-inducing oil shock. Between them, these two observations point to some obvious solutions to the long-term challenges of climate change and oil depletion—taxing oil or carbon, subsidizing alternative energy, redirecting public research funding, and offering cheap government insurance against the risks and decommissioning costs of nuclear power. The long-term response of Capitalism 4.0 to these issues is discussed at greater length in Chapter 19. But what could Western governments have done in the short-term to prevent the 2008 oil shock and the subsequent financial disaster—and what might governments do in the near future if another surge in the oil price to $150 a barrel were to threaten the global economy in the next few years?

…

But what could Western governments have done in the short-term to prevent the 2008 oil shock and the subsequent financial disaster—and what might governments do in the near future if another surge in the oil price to $150 a barrel were to threaten the global economy in the next few years? The fundamentalist view that market prices always reflect all possible information and lead to the best possible allocation of resources blinded governments and regulators to a crucial difference between the 2008 oil shock and the ones that occurred in 1974, 1979, and 1990. All earlier oil shocks were caused by geopolitical disruptions or deliberate OPEC actions that reduced the supply of oil. The surge in oil prices in 2008 was different. It was caused not by a shortfall in supply but an increase in demand. However, this demand was not due, as widely reported, to increased Chinese consumption.

…

Paulson CHAPTER ELEVEN - There Is No Can Opener The First Era of Economics The Second Era: Keynes’s Government-Led Economics The Third Era: The Triumph of Rational and Efficient The Next Transition CHAPTER TWELVE - Toward a New Economics Part IV - The Great Transition CHAPTER THIRTEEN - The Adaptive Mixed Economy Energy Policy and the 2008 Oil Shock CHAPTER FOURTEEN - Irresistible Force Meets Immoveable Object CHAPTER FIFTEEN - What—Me Worry? Will Rising Interest Rates Choke Off Economic Recovery? Will Printing Money Unleash Inflation? Will the Dollar Collapse? Part V - Capitalism 4.0 and the Future CHAPTER SIXTEEN - Economic Policy in Capitalism 4.0 Will There Be a Government Debt Crisis?

The End of Growth

by

Jeff Rubin

Published 2 Sep 2013

Regardless of what story made the most headlines at the time, oil prices were lurking at the root of the problem. Consider the first oil shock, created by the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) following the Yom Kippur War in 1973. Set off by this Arab-Israeli conflict, OPEC’s Arab members turned off the taps on roughly 8 percent of the world’s oil supply by cutting shipments to the United States and other Israeli allies. Crude prices spiked, and by 1974 real GDP in the United States had shrunk by 2.5 percent. The second OPEC oil shock happened during Iran’s revolution and the subsequent war with Iraq. Disruptions to Iranian production during the revolution sent crude prices higher, pushing the North American economy into a recession for the first half of 1980.

…

The stakes are high, and we can’t afford to lose, but we also have much to gain. [ CHAPTER 1 ] CHANGING THE ECONOMIC SPEED LIMIT THOSE WHO WERE AROUND IN THE 1970s will remember when speed limits were lowered in an attempt to stop drivers from burning so much gasoline. In the United States, the first OPEC oil shock spooked the president so much that he established a national speed limit of fifty-five miles per hour through the Emergency Energy Conservation Act. A slower speed limit didn’t win Richard Nixon any fans among car-loving voters, but his hand was forced by oil prices that were punishing the US economy.

…

From trading around $30 a barrel in 2004, oil prices marched steadily higher before hitting a peak of $147 a barrel in the summer of 2008. Unlike past oil price shocks, this time there wasn’t even a supply disruption to blame. The spigot was wide open. The problem was, we could no longer afford to buy what was flowing through it. There are many ways an oil shock can deep-six an economy. When prices spike, most of us have little choice but to open our wallets and shell out more for what we burn. Unless we want to stop driving our cars or burning heating oil, what else can we do? Something has to give. Paying more for oil means we have less cash to spend on food, shelter, furniture, clothes, travel and pretty much anything else you can think of.

A Brief History of Motion: From the Wheel, to the Car, to What Comes Next

by

Tom Standage

Published 16 Aug 2021

For the first time, American drivers realized they could not take the supply of gasoline for granted. The oil shock led the government to introduce a national speed limit of 55 mph, and fuel-economy standards that required American manufacturers to achieve an average fuel economy, across their entire product lines, of 18 miles per gallon by 1978 and 27.5 by 1985. But American carmakers did little to change their products. By the late 1970s, 80 percent of American-made cars still had V-8 engines. In 1979, in a second oil shock, oil supplies from the Middle East were once again disrupted, this time as a result of the Islamic revolution in Iran and the outbreak the following year of the Iran-Iraq War.

…

Perhaps a breakthrough in cellulosic-alcohol production could have led to a different world; but despite renewed efforts in the twenty-first century, such a breakthrough has yet to occur. And even if it had done so, oil would probably have remained a cheaper option—financially, at least. But relying on oil turned out to have other costs. OIL SHOCKS AND ELECTRIC DISAPPOINTMENTS Overproduction of oil, not scarcity, was the main concern in 1930s as the Depression reduced demand, even as new reserves were discovered. At one point a barrel of oil could be bought in Oklahoma for a mere forty-six cents. With the backing of the government, American oil companies were also expanding overseas, and by the mid-1930s they had won concessions in countries including Bahrain, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and Venezuela.

…

In 1979, in a second oil shock, oil supplies from the Middle East were once again disrupted, this time as a result of the Islamic revolution in Iran and the outbreak the following year of the Iran-Iraq War. The actual production of oil barely fell, but prices soared and panic buying ensued. This second oil shock stimulated the demand for smaller cars. Sales of small hatchbacks increased in Europe, while in America, more buyers were turning to imported cars, 80 percent of which came from Japan. As well as being more economical to run than much-larger American cars, models from Japanese brands such as Datsun, Toyota, and Honda also proved to be more reliable. By 1980, Japanese cars accounted for 16 percent of the American market, up from 3.5 percent in 1970.

Hubris: Why Economists Failed to Predict the Crisis and How to Avoid the Next One

by

Meghnad Desai

Published 15 Feb 2015

Early on during these developments, James Tobin (1918–2002), a distinguished economist at Yale and a Nobel Prize winner in 1981, proposed a tax on each forex transaction to slow down the hectic pace of the dealings. The world had never before seen so many currencies being required to carry on trade, and in which bonds and equities and other financial assets could be bought and sold. Tobin’s proposal is still being debated after 40-plus years. The Oil Shock Just at this juncture, inflation became a global problem. Decades of persistent full employment had strengthened the trade unions and made the wage demands of workers irresistible. There had been a notion for many years before World War II that the share of wages in total national income was constant.

…

Indeed the debate about the Phillips curve can be understood in this way. Could the workers be fobbed off with just nominal wage rises which could then be clawed back by inflation? The price of oil had not risen for nearly 50 years up until 1973. The Arab-Israeli War was one proximate reason for the oil shock. But the persistence of inflation meant that the purchasing power of the dollar, in which oil was priced, was eroding as far as oil exporters were concerned. The quadrupling of the price of oil in October 1973 was partly a political gesture, but it had a profound economic impact in terms of both theory and practice.

…

The rise in the price of oil increased costs of manufacturing, which were passed on to consumers in the form of higher prices. Dependence on imports for oil supplies meant that the developed economies had to transfer as much as 5 percent of their GDP to oil-exporting countries. Even as their imports became expensive, the rich countries’ exports were being priced out of the market. A side effect of the “oil shock” was felt by the financial system. The oil-exporting economies had limited scope for spending their newfound wealth. To begin with they chose to leave their wealth as bank deposits. Western banks found themselves flush with deposits. But to service them, they needed to loan them out and earn some interest.

Empty Vessel: The Story of the Global Economy in One Barge

by

Ian Kumekawa

Published 6 May 2025

A political move meant to curb American support for Israel, the embargo had catastrophic impacts on businesses around the world—not least shippers.[9] The world’s freight was carried over the oceans by gas-guzzling behemoths; in a day of steaming at normal speeds, a single container ship might burn through nearly one hundred tons of fuel. As the Yom Kippur War sent the price of marine diesel soaring, global shipping recoiled as if struck by a hammer. The oil shock did far more than just pop the container ship bubble; it was a boulder hurled into the economic sea, and its effects surged outward in mighty waves. In 1975, world manufactured exports fell for the first time since World War II.[10] Suddenly, the shipping industry’s plentiful supply of cargo space became an acute and glaring problem.

…

There is a major difference between trying to drill a hole into the Texas dirt and trying to drill a hole into an ocean floor through hundreds of feet of murky water, all while floating on the high seas, buffeted by gale force winds. Those conditions meant that the cost of offshore extraction is (and was) very high compared to drilling in the California scrub or the deserts of the Middle East. But the oil shocks of the 1970s, all caused by political unrest and violence in the Middle East, made wells in the North Sea significantly more attractive to investors and Western oil companies. Thus, at the same time that the oil crises were wreaking havoc on shipbuilders across northern Europe, they were breathing vitality into the region’s energy sector.

…

There, shipbuilders in once-bustling industrial cities like Liverpool, Newcastle, and Glasgow clamored for state protections akin to those furnished by Sweden.[73] Just as in Sweden, the shipbuilding trade in the United Kingdom had struggled in the 1950s and 1960s but was boosted by a surge of orders for container ships and tankers. Just like their Swedish counterparts, British shipbuilders gradually lost ground to Asian competitors that drew on lower-wage labor forces and more modern shipbuilding technology. As in Sweden, the oil shock of 1973 brought the simmering crisis to a boil. And just as in Sweden, Britain’s left-leaning Labour government intervened, bowing to pressure to save jobs in reliable political strongholds in the industrial north. In 1977, it nationalized thirty-two shipyards—97 percent of the country’s shipbuilding capacity.

Rethinking Islamism: The Ideology of the New Terror

by

Meghnad Desai

Published 25 Apr 2008

. The quadrupling of the oil price was a huge shock for the oil-dependent Western economies and it cost them percentoftheirnationalincome,whichwastransferredtothe OPECcountries,mainlySaudiArabia,theGulfEmiratesandIran. It was the largest such transfer in recent history. It amounted to $ billion at prices, and at today’s prices about ten times thatamount. The quadrupling of the oil price – the oil shock as it came to be known – was perhaps overdue. The price of a barrel of crude hadnotchangedfornearlyyears,whileinflationhadbeenacceleratingintheUSAandelsewheresince.Intheimmediate aftermath,ittriggeredstagflation,acombinationofhighinflation and high unemployment, in many developed countries. In the longer run, though, it helped them adopt better energy-saving technologies.

…

. This was, Bin Laden claimed, not the crisis of a single Muslim countrybutoftheummaitself. WhatenabledBinLadentoleverageanumberoflocalbattlesbetweenthereligiouspartiesandthesecularauthoritiesintoaglobal strugglewasthequiteindependentdevelopmentsthatwenowcall globalisation.Thiswasanotherstrandoftheforcesunleashedby andtheoilshock.ItledtoalossofcompetitivenessforWesternmanufacturingenterprisesandthemovementofmanufacturing awayfromtheWesterneconomies.Italsoledtoaproliferationof financialinnovationsandinstitutionsastheworldtriedtoabsorb the$billionofpetrodollarswhichsatinWesternbanksandhad to be loaned out to Third World governments. Western governmentssoonretrenched,abandonedKeynesianpoliciesandsqueezed inflation out of their economies. In the process the two AngloSaxoneconomies,theUSAandtheUK,begantoderegulatecapital movementssothatitstartedtoflowfreelytoallpartsoftheworld where there were market economies. Technological developments in information processing, telecommunications and transport at thesametimehadmadetravelandcommunicationscheapbeyond imagination.

…

. Technological developments in information processing, telecommunications and transport at thesametimehadmadetravelandcommunicationscheapbeyond imagination.TheWorldWideWebarrivedinthesandgave eventhemostisolatedindividualaccesstoinformationaboutthe meansofterrorandenabledcontactwithfriendsinanypartofthe world. The oil shock also accelerated international migration, which hadsloweddownaftertheFirstWorldWarandresumedafter but was still limited. Full employment in the West had created a need for unskilled labour which the periphery of the British, DutchandFrenchempireswasquitewillingtoprovide.

Road to Nowhere: What Silicon Valley Gets Wrong About the Future of Transportation

by

Paris Marx

Published 4 Jul 2022

Los Angeles was the premier automotive city, but by the 1960s it was beset by heavy smog produced by the exhaust fumes of all the vehicles zipping around the expanding communities of the basin. That prompted the federal government to invest in developing better electric vehicles, especially after the 1973 oil shock. But, once again, concepts by General Motors and the American Motor Company, as well as vehicles that made it into small-scale production such as Enfield Automotive’s two-seater Enfield 8000, failed to catch on. Not until the 1990s did the electric car get serious attention from the major automakers, spurring the slow creation of the modern electric vehicle industry.

…

His parents were engaging in an unconscious process that happens every single day when parents normalize the existing social conditions and downplay the harms that accompany them to their children. But in this case, it was not working, and that may have been a reflection of broader social dynamics playing out in the mid-1970s. Three years earlier, the world had experienced the first of the oil shocks of that decade. In October 1973, the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries declared an oil embargo on the countries supporting Israel in the Yom Kippur War, including the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada, but it also caused the price of oil to soar even for countries that were not embargoed.

…

By 1983, the New York Times was reporting that people had been using their bikes instead of their cars and going on walks to relieve their stress instead of taking long drives. People also wanted to economize on heating costs, which led them to keep their homes cooler in the winter and warmer in the summer, and the size of new homes actually shrank.4 The oil shocks of the 1970s presented a rare opportunity for the United States to rethink how it used energy and planned communities. President Jimmy Carter, who was inaugurated in January 1977, put solar panels on the White House and invested federal funds into developing renewable energy. But the change did not take hold, as anyone can see if they visit US towns and cities today, where most people continue to depend on their cars and trucks, not so much out of choice but necessity.

The End of Growth: Adapting to Our New Economic Reality

by

Richard Heinberg

Published 1 Jun 2011

Hamilton again: “At a minimum it is clear that something other than [I would say: “in addition to”] housing deteriorated to turn slow growth into a recession. That something, in my mind, includes the collapse in automobile purchases, slowdown in overall consumption spending, and deteriorating consumer sentiment, in which the oil shock was indisputably a contributing factor.” Moreover, Hamilton notes that there was “an interaction effect between the oil shock and the problems in housing.” That is, in many metropolitan areas, house prices in 2007 were still rising in the zip codes closest to urban centers but already falling fast in zip codes where commutes were long.34 FIGURE 27. Real Oil Prices and Recessions.

…

Charles Maxwell, quoted in Wallace Forbes, “Bracing For Peak Oil Production by Decade’s End,” Forbes.com, posted September 13, 2010; Eoin O’Carroll, “Pickens: Oil Production Has Peaked,” The Christian Science Monitor, posted June 18, 2008. 7. Clint Smith, “New Zealand Parliament Peak Oil Report: The Next Oil Shock?” Energy Bulletin, posted October 1, 2010, energybulletin.net/stories/2010-10-14/next-oil-shock; Stefan Schultz, “Military Study Warns of a Potentially Drastic Oil Crisis,” Spiegel Online, posted September 1, 2010; UK Industry study; US Joint Forces Command, The Joint Operating Environment 2010 (Suffolk, VA: USJFCOM, 2010). 8. See, for example, peakoil.net/headline-news/toyota-we-must-address-the-inevitability-of-peak-oil. 9.

…

In its authoritative 2010 World Energy Outlook, the IEA announced that total annual global crude oil production will probably never surpass its 2006 level.2 However, the agency fudged the question a bit by declaring that the peak was not due to geological constraints, and that total volumes of liquid fuels (including crude oil, biofuels, synthetic oil from tar sands and coal, and natural gas liquids like butane and propane) will continue to grow — just a bit — until 2035. In discussing the IEA report, a few analysts declared that these latter claims were essentially just efforts to avoid panicking the markets.3 BOX 3.1 Oil Shock 2011? In the early months of 2011 street demonstrations erupted in Iraq, Iran, Tunisia, Egypt, Bahrain, Yemen, Libya, and Algeria. Libya became mired in civil war, and its rate of oil exports fell from 1.3 million barrels per day to a small fraction of that amount. In Saudi Arabia, banned opposition groups threatened a “day of rage.”

Seven Crashes: The Economic Crises That Shaped Globalization

by

Harold James

Published 15 Jan 2023

But it is not just the interwar slump that led to a rethinking of what globalization is about, whom it hurts, and whom it benefits. Demand and Supply Not every crisis destroys or reverses globalization. On the contrary, some dramatic watershed events led to more rather than less globalization. In the 1970s, the oil shocks altered the policy paradigm. Initially more protectionism appeared as a response to big trade deficits in industrial countries, and as a remedy to exposure to global risk. The Cambridge Department of Applied Economics under Wynne Godley became a base for advocates of a siege economy. But instead of limiting trade, the policy community shifted to deregulation, disinflation, and more openness, with center-left governments leading the way: Jimmy Carter in the United States, James Callaghan in the UK, Helmut Schmidt in Germany.

…

The higher oil price might be regarded as the imposition of a new (wealth- and income-reducing) tax; and thus the industrial countries mostly decided not to adjust immediately. The immediate response in most countries was to accommodate the shock. That monetary and fiscal accommodation pushed inflation, which rose to 11.0 percent in the United States in 1974 (and then, after a second oil shock, to 12.0 percent in 1980), and to higher levels in some other countries: in the UK, consumer price index (CPI) inflation in 1975 was 24.2 percent, and in 1980 18.0 (see Figure 5.2). Countries employed differing strategies to reduce their fuel imports: France pushed nuclear energy as an alternative to carbon, the UK developed oil and gas fields in the North Sea, Germans and Japanese accepted greater fuel economy.

…

In the United Kingdom, where the balance of payments problem appeared earlier than elsewhere, the government tried a “Buy British” campaign, supported by all the major political parties. Leaders encouraged citizens to wear stickers and badges with the Union Jack and the message “I’m backing Britain.” (The press magnate Robert Maxwell distributed T-shirts with the same slogan, but they turned out to be made in Portugal.) In the mid-1970s, after the first oil shock, the government briefly flirted with what the left of the Labour Party called a “siege economy,” with extensive import restrictions. In the United States, there was acute anxiety about Japanese competition, and in 1981 Washington pressured Tokyo to sign an agreement that limited Japanese car exports.

Oil Panic and the Global Crisis: Predictions and Myths

by

Steven M. Gorelick

Published 9 Dec 2009

Recessionary pressures diminished only when the price of oil dropped during the 1980s, falling by nearly half from 1985 to 1986 ($27.56 to $14.43 per barrel). Although the spot price of oil in 2008 exceeded $145 per barrel, the 2008 average oil price took five years to double in inflation-adjusted terms; the price rise was much slower than during the 1970s’ oil shock. In terms of speed and magnitude, the oil price rise of 2008 itself was well tolerated by the economies of the world. It was the global financial crisis that began in 2008 that overwhelmed the world economy. Consequently demand and price dropped precipitously. Historically, the oil price increases of the 1860s, 1910s, and 1970s were each followed by a decade of declining oil prices.130 Before the economic crisis that began in 2008, the US economy stood up well to high oil prices for several reasons.

…

A second reason for the resilience of the US economy in the face of the high oil prices of 2008 was that, although China consumed more and more of the world’s oil, it produced cheap manufactured goods. Obtaining such inexpensive goods counterbalanced the inflationary impact of higher oil prices in the US. Third, a school of economic thought claims that there was a historical break in the effects of oil price shocks on economies such that subsequent oil shocks are not likely to be inflationary or cause a recession. Reasons for this break include decreased energy-use intensity, deregulation of key energy-producing and energy-consuming industries, and governmental monetary policy changes that have encouraged a low-inflation environment. However, as with many 6 Gasoline cost as a percent of 4 disposable income 2 0 1950 1970 1990 Figure 4.54 The cost of US gasoline consumption relative to personal disposable income.

…

However, as with many 6 Gasoline cost as a percent of 4 disposable income 2 0 1950 1970 1990 Figure 4.54 The cost of US gasoline consumption relative to personal disposable income. (Data: gasoline prices, EIA; US income, US Bureau of Economic Affairs) 2010 156 Counter-Arguments to Imminent Global Oil Depletion economic theories, it is not conclusive that any of these links is responsible for the relative insensitivity of the US economy to oil shocks.131,132 Myth VI: There Are No Substitutes for Oil Oil is different because there are no substitutes. This is another claim of those who maintain that the world is running out. But is it true? In terms of substitution, is oil different from other non-renewable commodities, such as copper and iron?

Earth Wars: The Battle for Global Resources

by

Geoff Hiscock

Published 23 Apr 2012

Long History on the Nuclear Road Japan had been travelling the nuclear road for 40 years, having opened the Fukushima plant in March 1971 in response to environmental concerns and the 1967 oil export embargo imposed by some Arab producers following the Six-Day War between Israel and its Arab neighbours. That brief embargo was followed by the much more severe “oil shock” of 1973–1974, when Arab producers within the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) declared sharp price rises, production cuts, and an oil embargo targeting the United States and some other Western nations over their support for Israel in its October 1973 Yom Kippur War with Syria and Egypt. This second oil shock encouraged Japan and other advanced economies to further embrace the nuclear option. A third oil shock came in 1979, when the Iranian Revolution disrupted production there, sending global oil prices higher.

…

Although they are able to recycle some from discarded computers, mobile phones, and other electronic detritus, they get most of their supply from China. In fact, between 50 and 60 percent of China’s rare earth exports go to Japanese buyers. But in September 2010, the buyers suffered something akin to a mini “oil shock.” Their supplies from China slowed to a crawl, tied down by the sort of bureaucratic double-shuffling that the Japanese themselves once employed as a nontariff barrier against unwanted imports. There was no export ban, the Chinese declared, but the result was the same: shipments ground to a halt, and the Japanese electronics industry got very nervous.

…

Its 58 reactors, operated by state majority-owned nuclear power utility Electricite de France (EDF), produce 75 percent of its electricity, and the country has so much spare capacity that EDF exports more than 10 percent of its output to neighbours such as Germany, Italy, Spain, Switzerland, Belgium, and the United Kingdom. Energy independence, a policy pursued by France since the oil shocks of the 1970s, is at the heart of nuclear power’s prominence in France, and even with the inroads made by renewable energy sources and cheaper gas, nuclear is unlikely to lose much ground. France actively champions its nuclear capabilities. Areva, another state-owned (90 percent) entity, is the world’s largest nuclear company, and has multiple agreements and joint ventures around the world aimed at securing uranium supplies, processing deals, technology development—such as with Siemens in Germany—and customers for its nuclear reactors.

The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power

by

Daniel Yergin

Published 23 Dec 2008

When the wave finally spent its fury two years later, the survivors would look around and find themselves beached on a totally new terrain. Everything was different; relations among all of them were altered. The wave would generate the Second Oil Shock, carrying prices from thirteen to thirty-four dollars a barrel, and bringing massive changes not only in the international petroleum industry but also, for the second time in less than a decade, in the world economy and global politics. The new oil shock passed through several stages. The first stretched from the end of December 1978, when Iranian oil exports ceased, to the autumn of 1979. The loss of Iranian production was partly offset by increases elsewhere.

…

Not only were those developing nations hit by the same recessionary and inflationary shocks, but the price increases also crippled their balance of payments, constraining their ability to grow, or preventing growth altogether. They suffered further from the restrictions on world trade and investment. The way out for some was to borrow, and therefore, a goodly number of those OPEC surplus dollars were "recycled" through the banking system to these developing countries. Thus, they coped with the oil shock by the expedient of going into debt. But a new category also had to be invented—the "fourth world"—to cover the lower tier of developing countries, which were knocked flat on their backs and whose poverty was reinforced. The new and very difficult problems of the developing countries put the oil exporters into an awkward, even embarrassing situation.

…

For, most forecasters agreed, another oil crisis was highly probable a decade or so hence, in the second half of the 1980s, when demand would once again be at the very edge of available supply. The result, in popular parlance, was likely to be an "energy gap," a shortage. In economic terms, any such imbalance would be resolved by another major price increase, a second oil shock, as had happened in the early 1970s. Though variations were to be found among the forecasts, there was considerable unanimity on the central themes, whether the source was the major oil companies, the CIA, Western governments, international agencies, distinguished independent experts, or OPEC itself.

State of Emergency: The Way We Were

by

Dominic Sandbrook

Published 29 Sep 2010

‘I realised very quickly’, said Anthony Barber, ‘that all we’d been trying to achieve was really coming to an end.’46 But it is also a myth that the oil shock was always bound to bring doom and disaster in its wake. In the United States – which was punished even more severely than Britain, because of its support for Israel – the Nixon and Ford administrations managed to weather the economic blizzard without plunging the economy into a devastating bout of inflation, and although there was a prolonged and painful recession, the American economy was in recovery by early 1976. But coming after three draining years of industrial conflict, pay restraint and rhetorical class warfare, the oil shock brought out the very worst in British politics.

…

The NUM was still considering the Coal Board’s offer when, on 16 October, OPEC broke the devastating news of their oil price rise, which changed the game completely. Not only did the oil shock put Heath’s counter-inflation policy under intense pressure, it left the miners in an even stronger position. Britain depended heavily on imported oil to meet its energy requirements; indeed, since 1972 the government had been quietly building up coal stocks by burning more oil instead. Thanks to the oil shock, however, the government could hardly rely on imported oil if negotiations with the miners broke down; indeed, with North Sea oil yet to come on stream, OPEC’s blackmail had left Britain more dependent on coal than ever.

…

After toiling through ‘years of austerity … suddenly here it all was, the world of Penthouse and the Beatles, the world of large steaks and double cream on real gateaux, the world of girls and nightclubs and expense account champagne’.9 And even though millions of people never went to nightclubs or quaffed champagne, they still enjoyed their slice of the ever-expanding cake. By 1973, one in three people told researchers they had gone out for a meal in the previous month, a luxury few of their parents could have imagined. And despite all the economic turmoil of the early 1970s, the strikes and inflation, the oil shock and the power cuts, most of Bexley’s voters remained far more prosperous than they could have expected twenty years before. Three years after Edward Heath had walked into 10 Downing Street, there were more cars on the roads than ever, more products on the supermarket shelves, more colour televisions in suburban homes, more planes taking off for the beaches of Spain.10 As a relatively affluent, Conservative-voting slice of London suburbia, Bexley was not exactly representative of the national experience at the dawn of the 1970s.

The Atlantic and Its Enemies: A History of the Cold War

by

Norman Stone

Published 15 Feb 2010

The oil producers, left to themselves, would have been far too disunited for common action, and their common strategy at OPEC did not in fact last for very long. But the fall of the dollar in 1971 pushed them together: why accept valueless paper dollars? The same was true, though not to the same extent, for producers of other raw materials - coffee, tobacco, copper, rubber, iron ore, meat as well - and prices shot up, even in 1971, two years before the oil shock. The problem was symbolized by the Brazilian city of Manaos, deep in the jungle. There, once upon a time, rubber had appeared, and the place became opulent: famously Dame Adeline Patti, the great opera singer of the 1890s, appeared there. Then rubber was produced elsewhere, and Manaos relapsed back into semi-jungle.

…

For a time, this seemed to work. Unemployment did indeed fall to 500,000, but this was classic fool’s gold. The ‘fringe banks’ for a time did well out of property prices, which had a dangerously more important role in England than elsewhere, and unlovely concrete spread and spread and spread. But then came the oil shock. Even food prices trebled by 1974 as against 1971, and the bubble burst in November 1973, when the minimum lending rate was pushed up to 13 per cent while public spending was cut back by £12bn. One of the new banks could not obtain credit, and the other banks had to set up a ‘lifeboat’. It was not enough.

…

By 1976 the Treasury itself was somewhat converted to the idea of monetarism, a limitation of the quantity of money such that inflation could be contained. But the conversion was not enthusiastic. The Bank (and the City) expressed greater enthusiasm. It was an unhappy time, the country winding down, and a slow crisis started. In 1976-7 the world economy did pick up, as the oil-shock money was recycled back to the industrial and exporting countries (which grew overall at 5 per cent). But the British economy was by now too fragile to gain much more than a respite, and inflation still ran high - 25 per cent in 1975, 16 per cent in 1976 and in 1977 (earnings keeping apace until 1977).

War and Gold: A Five-Hundred-Year History of Empires, Adventures, and Debt

by

Kwasi Kwarteng

Published 12 May 2014

Contemporaries spoke of the ‘Great Recession’. It was recalled that the ‘price of oil had actually been falling through most of the postwar period, both absolutely and in relation to other world prices’.17 The oil shock of 1973 led to ‘visions of financial disaster for the west’. The spike in oil prices had increased all costs in the Western economies, which were heavily dependent on oil. ‘Prices were higher and employment lower’ as a consequence of the oil shock.18 Despite the arguments of a later generation of economists, contemporaries were very clear about the direct causal link between higher oil prices, increased inflation and stagnant economies.

…

The Saudis had bought ‘all over the world and they sent the goods home’, but then they ‘couldn’t get anything off the ships and into use’.26 Increased revenues, which flowed into the treasuries of the oil-exporting countries, altered the international economic environment. David Rockefeller, scion of the wealthy dynasty and Chairman of the Chase Manhattan Bank, recalled that the ‘most immediate effect of the oil shock was the surge in the flow of dollars from oil-importing nations into OPEC’s coffers. Between 1973 and 1977, the earnings of the oil-exporting nations expanded 600 percent, to US$140 billion.’ There lay the problem confronting the world monetary system. The enormous dollar reserves acquired by the oil exporters needed to find some outlet.

…

Loans were also extended to Latin America, Africa, East Asia and other parts of the developing world.30 Other American bankers and senior officials began to express anxiety about the political and economic outlook. Paul Volcker, the future Chairman of the Federal Reserve, remembered that by mid-decade the ‘combination of accelerating inflation and the oil shock late in 1973’ went far in ‘establishing floating currencies as the . . . international monetary system’. The mid-1970s were marked by ‘what was then the most serious of the postwar recessions’ and by ever-higher inflation. Floating currencies, and the end of any link to gold, were a novel feature of the period.

The Quest: Energy, Security, and the Remaking of the Modern World

by

Daniel Yergin

Published 14 May 2011

It was primarily a credit recession, the result of too much debt, too much leverage, too many derivatives, too much cheap money, too much overconfidence—all of which engendered real estate and other asset bubbles in the United States and other parts of the world. But the surge in oil prices was an important contributing factor to the downturn. Between June 2007 and June 2008, oil prices doubled—an increase of $66—in absolute terms, a far bigger increase in oil prices than had ever been seen in any of the previous oil shocks, going back to the 1970s. “The surge in oil prices was an important factor that contributed to the economic recession,” observed Professor James Hamilton, one of the leading students of the relation between energy and the economy. The oil price shock interacted with the housing slowdown to tip the economy into a recession.

…

The embargo, combined with the price increases, shook the structure of international relations and sent shock waves through the global economy, followed by several years of poor economic performance. The 1978–79 Iranian Revolution, which toppled the shah and ushered in the theocratic Islamic Republic, also ignited a worldwide panic in the petroleum market and another oil shock that contributed mightily to the difficult economic years of the early 1980s. Saddam Hussein’s 1990 invasion of Kuwait set off the Gulf crisis, leading to the loss of five million barrels a day of supply from Iraq and Kuwait. Other producers, notably Saudi Arabia, cranked up output and largely replaced the missing barrels over the next several months, even before Operation Desert Storm evicted Saddam’s forces from Kuwait.

…

In Japan, too, nuclear power plants continued to come online—with more than a dozen in the decade following Chernobyl’s meltdown. But Japan’s cultural legacy regarding nuclear power was more complicated. It was the only country to have ever suffered a nuclear attack, and the politics of nuclear power could engender a powerful emotional response from voters and politicians alike. But the oil shocks of the 1970s, which threatened to undermine Japan’s postwar economic miracle, were deeply traumatic. Indeed, so much so that the political will to support the nuclear program remained strong. “Unlike the United States or the United Kingdom, Japan had no choice but to depend on imports for virtually all of its fossil-fuel supply,” said Masahisa Naitoh, a formerly senior energy official in Japan.

The World's Banker: A Story of Failed States, Financial Crises, and the Wealth and Poverty of Nations

by

Sebastian Mallaby

Published 24 Apr 2006

The institution’s war on poverty, like America’s war on communism in Vietnam, was proving all too much for it. Without pressure from outside, McNamara might have soldiered on, preaching the cause of development at the Bank’s annual meetings each autumn, and driving his staff to come up with new ways of advancing it. But outside pressure did arrive—in the form of two successive oil shocks. McNamara’s speech in Nairobi in 1973 had been followed almost immediately by the Yom Kippur War and the Arab oil embargo; oil prices shot up, and the Bank’s oil-importing clients suddenly found their trade balance deteriorating. For a while, the pain could be postponed. The Arabs parked their windfall in Western banks, so credit became cheap; countries simply borrowed to finance imports.

…

But the Bank was on the one hand a public-sector institution, and on the other hand a promoter of free-market reform. It therefore qualified as a target for both ends of the political spectrum. In this ideological climate the “structural adjustment” lending that McNamara had proposed as a pragmatic response to the oil shock became bitterly contentious. The Bank rightly urged developing countries to devalue their currencies, a policy that they should have embraced much sooner after the 1973 shock; expensive oil was affordable only if countries boosted their exports, and that meant making their goods competitive by having a low exchange rate.

…

Adjustment was controversial from the outset, as we have seen: it was enthusiastically supported by the Bank’s Bretton Woods sister, the International Monetary Fund, but agencies like the United Nations Development Program and UNICEF were less inclined to blame Africa’s problems on policies that needed adjustment, and more apt to point the finger at the oil shock, falling commodity prices, and other misfortunes not of Africa’s own making. African leaders, not surprisingly, sided with the United Nations, and denounced the Bank’s new orthodoxy as anti-African: They wanted aid, not policy lectures.15 The Bank soon found itself prescribing the bitter medicine of economic austerity while others declared that its diagnosis was all wrong; and the sense that its credibility was on the line drove the Bank to redouble its efforts on the continent.

Living in a Material World: The Commodity Connection

by

Kevin Morrison

Published 15 Jul 2008

In the simplest of acts we take raw materials for granted; like switching on a light or turning up the heating. I wanted to show T 2 | LIVING IN A MATERIAL WORLD how commodities are relevant to every body, every day – and how they are more relevant now than they have been at any time since the last oil shock nearly three decades ago (my memories of which include going to bed by candlelight during the energy rationing and three-day weeks of the 1970s). Everything we consume – whether through buying something, eating or even our physical actions – involves, at some level, the use of metals, fossil fuels or agricultural produce, which we take from planet Earth and use to make our lives more comfortable, more productive or more manageable.

…

Economic growth in developing countries has accelerated global growth at a faster pace than at any time since the 1960s. In the 1950s and 1960s, the world economy rose by 5 % due to the reconstruction of Europe and Japan, as well as the economic competition between the US and the Soviet Union. The two oil shocks in the 1970s slowed growth to about 4 %, and then to 3 %, which became the average economic growth rate of the 1980s and 1990s. Higher oil and food prices together with the credit crisis in the US have prompted economists to cut global economic growth rates to around 3 % for 2008. Some experts cite this as the start of a prolonged downturn in the global economy.

…

The credit crisis of 2007 followed a prolonged period of loose money supply where interest rates were kept below their long-term average. The combination of easy credit and high oil prices is eerily similar to the economic conditions in the early and late 1970s at the time of the world’s first two oil shocks, both of which were followed by recessions.3 The 1970s was the last time the world was seriously concerned about the supply and price of raw materials, and I refer to this period throughout the book.4 In December 1976, the US government issued a report on resource availability by the National Commission on Supplies and Shortages,5 8 | LIVING IN A MATERIAL WORLD which looked at the issue of whether the US was running out of resources and whether the country was dependent on importing raw materials from foreign countries (Eckes, 1978).

The Great Race: The Global Quest for the Car of the Future

by

Levi Tillemann

Published 20 Jan 2015

His father was a Lithuanian-born scrap metal dealer, and as a young man Ovshinsky himself had started his career as a lathe operator. Ovshinsky’s formal education went only as far as high school, but the public libraries were a fitful schoolroom for such a subversive genius. His self-directed study nurtured a deep streak of intellectual independence. Long before the oil shocks of the 1970s, Ovshinsky understood the environmental and geopolitical dangers of relying too much on oil to fuel an economy and set out to find alternatives. Together with his wife, Iris, he set up a “storefront lab” that eventually grew into the publicly traded company ECD Ovonics. At Ovonics, Ovshinsky invented a new family of semiconductors, hydrogen fuel cells, and thin-film solar cells.

…

And so, he dryly told Angelenos, “faced with a choice between my freedom and your mobility, my freedom wins.”14 The Ruckelshaus EPA responded by proposing that the federal government should curtail development and ration gasoline shipments to California by 25 percent in summer months, with most of the cuts targeted toward the Los Angeles basin.15 Obviously, this would not be good for California’s economy—or for the automakers, or oil companies. So many in the business-minded community quickly learned to despise the EPA. Automakers in particular felt as if they were under siege: they were being required to both reduce emissions and increase fuel economy—in response to the oil shocks—at the same time. The technological burden was staggering. Technology Forcing—“Impossible” Standards All of this was very much in line with the new thinking at CARB. Tom Quinn’s attitude did not endear him to the automakers—not one bit. And under Quinn’s leadership CARB forced manufacturers out of their comfort zones—mining them for data about what was possible and pushing them precariously close to the technology frontier.

…

Sometimes he would write press releases during the automakers’ testimony in order to beat industry execs to the media punch.18 Other times he would just leave a hearing for hours, return, call for a vote mid-testimony, and adjourn.19 He had little patience for Detroit’s carefully crafted lobbying campaigns and public relations stagecraft. Some would argue that Quinn went too far. The new CARB chairman carried out policy irrespective of economic conditions and seemed impervious to the difficulties faced by Detroit. Japanese imports were surging, and the first oil shock had tremendously weakened the appeal of America’s biggest, most profitable cars. And the industry’s problems did not stop there. Quality was starting to sag. By the early 1970s, the average American-made car went to market with more than two dozen defects.20 But despite these tough times, Quinn was intent on making California into America’s pressure cooker for new environmental technologies.

Postcapitalism: A Guide to Our Future

by

Paul Mason

Published 29 Jul 2015

The break occurs at the end of the First World War; the 1930s Depression, followed by the destruction of capital during the Second World War terminate the downswing. Late-1940s–2008: In the fourth long cycle transistors, synthetic materials, mass consumer goods, factory automation, nuclear power and automatic calculation create the paradigm – producing the longest economic boom in history. The peak could not be clearer: the oil shock of October 1973, after which a long period of instability takes place, but no major depression. In the late–1990s, overlapping with the end of the previous wave, the basic elements of the fifth long cycle appear. It is driven by network technology, mobile communications, a truly global marketplace and information goods.

…

Even Japan – which had averaged growth rates close to 10 per cent in the post-war period – went briefly negative.24 The crisis was unique because in the worst-hit countries falling growth coincided with high inflation. By 1975, inflation in Britain reached 20 per cent, and 11 per cent in the USA. The word ‘stagflation’ hit the headlines. Yet even at the time it was obvious that the oil shock was merely the trigger. The upswing had already been stuttering. In each developed country, growth in the late 1960s seemed beset by national or local problems: inflation, labour troubles, productivity concerns and flurries of financial scandal. But 1973 was the watershed, the point where the energy driving the fourth wave upwards caused it to peak and then invert.

…

With this change, each stricken country was temporarily free to solve the underlying problems of productivity and profitability in ways the old system had made impossible: with higher state spending and lower interest rates. The years 1971–3 were lived in a kind of nervous euphoria. The inevitable stock market crash hit Wall Street and London in January 1973, triggering the collapse of several investment banks. The oil shock of October 1973 was the final straw. CARRY ON KEYNES By 1973, every aspect of the unique regime that had sustained the long boom was broken. But the crisis looked accidental: low input prices destroyed by OPEC; global rules ripped up by Richard Nixon; profits eroded by that figure of loathing, the ‘greedy worker’.

A Pelican Introduction Economics: A User's Guide

by

Ha-Joon Chang

Published 26 May 2014

This created instability in the world economy, with currency values fluctuating according to market sentiments and becoming increasingly subject to currency speculation (investors betting on currencies moving up or down in value). The end of the Golden Age was marked by the First Oil Shock in 1973, in which oil prices rose fourfold overnight, thanks to the price collusion of the cartel of the oil-producing countries, OPEC (Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries). Inflation had been slowly increasing in many countries since the late 1960s but, following the Oil Shock, it shot up. More importantly, the next several years were characterized by stagflation. This newly coined term referred to the breakdown of the age-long economic regularity that prices fall during a recession (or stagnation) and rise during a boom.

…

The war resulted in the first reversal in the acceleration in economic growth since the early nineteenth century.19 1945–73: The Golden Age of Capitalism Capitalism performs well on all fronts: growth, employment and stability The period between 1945, the end of the Second World War, and 1973, the first Oil Shock, is often called the ‘Golden Age of capitalism’. The period really deserves the name, as it achieved the highest growth rate ever. Between 1950 and 1973, per capita income in Western Europe grew at an astonishing rate of 4.1 per cent per year. The US grew more slowly, but at an unprecedented rate of 2.5 per cent.

…

This newly coined term referred to the breakdown of the age-long economic regularity that prices fall during a recession (or stagnation) and rise during a boom. Now, the economy was stagnating (albeit not exactly in a prolonged recession, like during the Great Depression) but prices were rising fast, at 10, 15 or even 25 per cent per year.27 The Second Oil Shock in 1979 finished off the Golden Age by bringing about another bout of high inflation and helping neo-liberal governments come to power in the key capitalist countries, especially in Britain and the US. This period is often depicted as one of an unmitigated economic disaster by free-market economists, who are critical of the mixed economy model.

The Vanishing Middle Class: Prejudice and Power in a Dual Economy

by

Peter Temin

Published 17 Mar 2017

The Fed had been securing the exchange rate for the previous quarter century, and it had to learn how to fulfill its new role. This process was complicated greatly when the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) quadrupled the price of oil in 1973. The resulting “Oil Shock” sent many prices—including exchange rates—in motion.3 Anticipation of the Oil Shock led President Nixon to propose “Project Independence” in November 1971. Nixon’s emphasis was on domestic production and consumption, and his policy implied that the United States was to remain passive in the face of OPEC provocation. This idea was transformed over the next few years into a more active stance that would seek steady supplies of oil from the Middle East.

…

This idea was transformed over the next few years into a more active stance that would seek steady supplies of oil from the Middle East. Nixon also replaced the ailing draft for Army soldiers with the volunteer army at this time, a plan he also started before the Oil Shock. The draft had become difficult as the Vietnam War dragged on, and conservatives argued against the idea of forced service. This was an early step in the privatization of the military.4 The Oil Shock also raised the question of how the members of OPEC were going to hold their newly acquired wealth. The highly regulated financial system established at Bretton Woods in the 1940s could not easily absorb this large inflow of cash, and the cash found a temporary home in the arrangement for dollar deposits outside the United States.

Aerotropolis

by

John D. Kasarda

and

Greg Lindsay

Published 2 Jan 2009

What we couldn’t phase out was gasoline—which continues to fuel 95 percent of all vehicles—although consumers rushed to embrace fuel-efficient Japanese imports, just as they do now. As a consequence, transportation’s oil consumption grew by about 1.3 percent per year between the first oil shock of 1973 and the 2008 peak. But residential uses fell 2.1 percent, commercial uses 2.4 percent, and power generation 4.8 percent. Americans use half as much energy per capita as they did in 1973. While the decade’s oil shocks weren’t enough to wean us off fossil fuels—“the moral equivalent of war” in President Carter’s famous formulation—they did spur us to greater efficiency. Before the crisis in 1973, global oil consumption grew 8 percent a year.

…

The number of passengers in the United States this year is expected to hover around seven hundred million, 10 percent off its peak but still triple what it was in 1980. It’s grown five times faster than population since then. In thirty years, the number of miles flown by Americans dipped only once before our current crisis, in the wake of 9/11. Neither the early eighties oil shocks nor the first Gulf War slowed us down. Air travel follows the money. It’s a leading indicator of economic health, flying higher when times are good and falling faster when they turn bad. As it is, six hundred thousand Americans hopped a flight last week, more than the population of Milwaukee. Hubs are easily the world’s most central places, concentrating us like nowhere else.

…

This was hardly unexpected—Sheikh Mohammed’s father, Sheikh Rashid, knew it not long after oil was discovered in the 1960s. The knowledge defined Dubai, forcing its rulers to diversify and imagineer. While Abu Dhabi threw up topaz and tourmaline towers Dallas-style in the 1970s, Sheikh Rashid plowed his oil-shock profits into infrastructure. It was during his reign that Dubai built its ports, airport, drydocks, World Trade Center, and the first banks and hotels to cater to traders like Marwan Bibi. His greatest legacy was Jebel Ali, the largest man-made harbor ever created, carved from a stretch of empty beach.

Two Nations, Indivisible: A History of Inequality in America: A History of Inequality in America

by

Jamie Bronstein

Published 29 Oct 2016

During the Nixon administration, the President’s Commission on Income Maintenance recommended a basic income guarantee for low-income Americans, the Family Assistance Plan. The plan was never enacted, although the Earned Income Tax Credit had its origin in this idea. When the Family Assistance Plan stalled and died, the political will to broaden the social safety net evaporated under economic pressure. Stagflation, the oil shocks of the 1970s, and deindustrialization brought malaise to the United States. These conditions enabled widespread acceptance of an alternative theory of prosperity, discussed in Chapter 7. Divorced from both equality of condition and equality of opportunity, Ronald Reagan’s tax cuts, military spending, safety-net slashing, and “trickle-down” economics promoted the idea that the freest markets were most efficient, and the most efficient markets produced the most prosperity.

…

The philosophers John Rawls’s A Theory of Justice (1971) and Robert Nozick’s Anarchy, State, and Utopia (1974) set out important interpretations of fair property-holding and distribution that have influenced divergent policies to this day. By the late 1970s, prosperity was lagging under the pressure of two oil shocks, unprecedented combined inflation and unemployment, and increasing American deindustrialization. The population shifted, following military bases and factories to southern states where unions were weaker or nonexistent and workers could be paid less. In the Rust Belt, the automobile factories that drove American prosperity furloughed workers.7 In the midst of this malaise, new voices began to blame the economic slowdown on Keynesian economics, taxation, and government economic regulation.

…

In the worst formulation, they described the poor as devious “welfare queens.”100 As the next chapter will show, Ronald Reagan, long an opponent of welfare programs, made those associations and claims central tenets of his administration. Under the pressure of neoliberalism, the Great Compression quickly began to unravel. CHAPTER 7 The Triumph of Neoliberalism: 1979–1999 Stagflation and the oil shocks of the 1970s had brought economic malaise to the United States, setting the stage for widespread acceptance of a new, “neoliberal” theory of prosperity, divorced from both equality of condition and equality of opportunity. Over the course of the next decade, Ronald Reagan’s severe tax cuts and George H.

The People's Republic of Walmart: How the World's Biggest Corporations Are Laying the Foundation for Socialism

by

Leigh Phillips

and

Michal Rozworski

Published 5 Mar 2019

But Fed governors were explicit that they had deliberately applied the brakes to the economy and altered the costs of investment in order to change the climate in which capital bargained with workers. They planned, overriding what the (labor) market, left to its own devices, would otherwise have delivered. Similarly, during the first eight months of the 1973–75 oil-shock recession, interest rates continued to rise—nicely coinciding with UAW bargaining with the Big Three automakers. When the Fed finally lowered rates to stimulate investment and counteract the slump, Fed governors argued that, unlike expansionary fiscal policy carried out by Congress and the president, presumably at the behest of the democratic will, their independent actions would be much easier to undo when the economy “overheated” again and workers started to ask for more.

…

Rather than planning only how much healthcare there was, and where—the important questions that the 1960s planners had to tackle first—these reforms could also have laid the groundwork for planning that tackled how healthcare was produced and, most importantly, who participated in decision making. However, instead of ratcheting up democracy within the system, most of the 1970s reforms failed in the face of brewing economic crisis. The oil shock of the early 1970s saw both prices and unemployment spike at the same time—something that economists of all mainstream stripes had said was no longer supposed to happen. The regime of boom and bust was supposed to have been solved by Keynesianism, delivered by the postwar compromise between capital and labor.

…