The Sharing Economy: The End of Employment and the Rise of Crowd-Based Capitalism

by

Arun Sundararajan

Published 12 May 2016

Getaround is growing rapidly, fuelled in part by over $40 million in venture financing, and a bet that its “Instant” model—where you can get a car as soon as you book it without owner approval—is what will really shift behavior from buying to sharing. Its peer-to-peer rental model is a central part of the sharing-economy narrative, the perfect confluence of two ideas: access without ownership and networks replace hierarchies. But there haven’t yet been any large-scale, digital, peer-to-peer rental marketplaces for assets other than automobiles. Snapgoods was an early effort at creating a peer-to-peer rental marketplace for everything from power saws to Roombas, but it couldn’t find a profitable business model. Marketplaces that enable the rental of expensive equipment owned by people who aren’t very wealthy might represent a new pocket of opportunity.

…

Marketplaces that enable the rental of expensive equipment owned by people who aren’t very wealthy might represent a new pocket of opportunity. For example, KitSplit, funded in 2014 by NYU students Lisbeth Kaufman and Katrina Budelis, is a peer-to-peer rental marketplace for independent filmmakers to get cameras, lenses, Oculus Rift headsets, and other professional equipment from each other. But as of late 2015, other success stories that have scaled are hard to find, and peer-to-peer rental activity is often conducted through bulletin-board-esque services like Alan Berger’s NeighborGoods. Many others have successfully facilitated household asset rental using a different, more traditional form of organizing short-term borrowing: the library.

…

However, unless the product is sufficiently valuable, the coordination costs associated with a rental market become too high relative to the value gained from renting (or renting out). Thus, peer-to-peer rental of $30,000 cars makes sense, and of $100 vacuum cleaners less so. Gansky’s framework provides an elegant starting point for assessing how likely it is to see crowd-based capitalism emerge for different product categories. As I discussed in the introduction, we have seen peer-to-peer rental markets emerge for cars in several countries, such as the United States (Getaround), France (Drivy), and the Netherlands (SnappCar). By Gansky’s logic, we might also expect a great deal of activity in the market for high-end luxury products like Rolex watches.

What's Mine Is Yours: How Collaborative Consumption Is Changing the Way We Live

by

Rachel Botsman

and

Roo Rogers

Published 2 Jan 2010

It is estimated that just shifting a fifth of household spending from purchasing to renting would cut emissions by about 2 percent—or 13 million tons—of CO2 a year.16 The second hurdle facing peer-to-peer rental is security and trust. Do you want to rent out your Nintendo Wii to someone you don’t know, even if it earns you, say, $25? Peer-to-peer rental sites have several layers of security. Every transaction is backed up by a contract that lays out the legal terms. Renters are also required to leave a deposit and can opt for insurance in case the item is lost or stolen in their care. And just as with eBay and Airbnb, review and ratings tools enable the community to self-regulate who can be lent to in good faith. For these services, the peer-to-peer rental companies charge about a 6 percent commission on every transaction.

…

To illustrate the explosive rise of Collaborative Consumption, let’s first look at the growth stats behind a few mainstream examples: Bike sharing is the fastest-growing form of transportation in the world, with the number of programs expected to increase by 200 percent in 2010.2 Zilok, a leader in the peer-to-peer rental market, has grown at a rate of around 25 percent since it was founded in October 2007.3 Two billion dollars worth of goods and services were exchanged through Bartercard, the world’s largest business-to-business bartering network in 2009, up by 20 percent from 2008.4 Zopa did more business in its fifth year, at £35.5 million (March 2009 to March 2010), than in the previous four years combined at £34.5 million.

…

The more established companies are making hundreds of millions in revenue (Netflix made $359.6 million and Zipcar $130 million in 2009), while others like SolarCity and SwapTree are just starting to turn a profit. Specific sectors of Collaborative Consumption are predicted to experience phenomenal growth over the next five years. The peer-to-peer social lending market led by the likes of Zopa and Prosper is estimated to soar by 66 percent to reach $5 billion by the end of 2013.10 The consumer peer-to-peer rental market for everything from drills to cameras is estimated to be a $26 billion market sector. The swap market just for used children’s clothing (0 to 13 years) is estimated to be between $1 billion and $3 billion in the United States alone.11 Car sharing or per hour car rental is predicted to become a $12.5 billion industry.

After the Gig: How the Sharing Economy Got Hijacked and How to Win It Back

by

Juliet Schor

,

William Attwood-Charles

and

Mehmet Cansoy

Published 15 Mar 2020

In 2010 three Harvard Business School students went ahead with the P2P model anyway and started RelayRides.29 We Are the “Uber of X” Within a few years startups were being founded at a frenzied pace, with many describing themselves as “the Uber of x.”30 Investors poured an astonishing $23 billion into the sector between 2010 and 2017.31 Researchers began predicting that Uberization “might replace the modern corporation.”32 One journalist cataloged 105 American “Uber for x’s” founded between 2009 and 2019.33 Transportation sites offered real-time ridesharing (with drivers who were making trips for their own purposes rather than to earn), jitney services, and apps that promised to treat drivers better than Uber and Lyft. Peer-to-peer rental schemes emerged for boats, airplanes, bicycles, and cars left at airports while their owners were traveling. In lodging, the offerings were less varied, perhaps because Airbnb had hit upon a winning formula.34 Platforms specializing in “idle capacity” grew, offering parking spaces, yards (for gardening), attics, and storage space.

…

Brussels: European Parliament. www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2017/614184/IPOL_STU(2017)614184_EN.pdf. Foster, Sheila, and Christian Iaione. 2017. “Ostrom in the City: Design Principles for the Urban Commons.” www.thenatureofcities.com/2017/08/20/ostrom-city-design-principles-urban-commons. Fraiberger, Samuel P., and Arun Sundararajan. 2017. “Peer-to-Peer Rental Markets in the Sharing Economy.” SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2574337. Frank, Thomas. 1997. The Conquest of Cool: Business Culture, Counterculture, and the Rise of Hip Consumerism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ———. 2000. One Market under God: Extreme Capitalism, Market Populism, and the End of Economic Democracy.

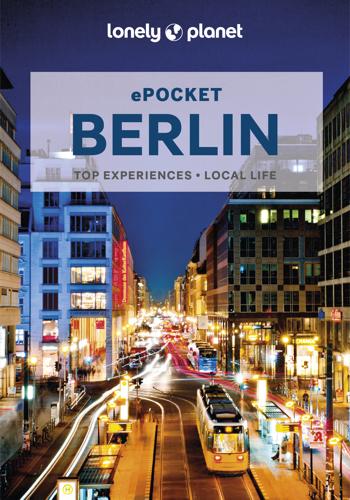

Pocket Berlin

by

Andrea Schulte-Peevers

Published 15 Mar 2023

Local SIM cards can be used in unlocked multiband phones. Time Central European time (GMT/UTC plus one hour) Tipping Servers 10%, bartenders 5%, taxi drivers 10%, porters €1 to €2 per bag, room cleaners €1 to €2 per day, toilet attendants €0.50. Daily Budget Budget: Less than €125 Dorm bed or peer-to-peer rental: from €25 Doner kebab: €5–6 Club cover: €10–25 Public transport 24-hour ticket: €8.80 Midrange: €125–250 Private apartment or double room: €100–150 Two-course dinner with wine: €50–80 Guided tour: €15–30 Museum admission: €8–20 Top end: More than €250 Upmarket apartment or double in top-end hotel: from €200 Gourmet multi-course dinner with wine pairing: €180–400 Cabaret ticket (good seats): €60–150 Taxi ride: €25 Advance Planning Two to three months before Book tickets for the Berliner Philharmonie, the Staatsoper, Sammlung Boros and top-flight events.

Lonely Planet Pocket Hong Kong

by

Lonely Planet

Don’t be afraid to ask for a fork if you can’t manage chopsticks. Queues Hong Kongers line up for everything. Attempts to jump the queue are frowned upon. TIPPING Tipping isn’t expected in Hong Kong and is usually reserved for particularly good service. DAILY BUDGET Budget: Less than HK$1000 • Dorm bed or peer-to-peer rental: from HK$150 • Bowl of noodles: HK$40–150 • Beer: HK$50–100 per pint • Public transport 24-hour ticket: HK$65 Midrange: HK$1000–3000 • Private apartment or double room: HK$400–800 • Two-course dinner with wine: HK$400–600 • Cocktail: HK$80–200 • Museum: HK$10–120; most free Wednesdays Top End: More than HK$3000 • Apartment or double in top-end hotel: HK$1200–5000 • Gourmet multi-course dinner with wine: HK$1500–3000 • Theatre show (good seats): HK$300–500 • Red urban taxi: HK$24 plus HK$1.70 for every 200m Currency Hong Kong dollar HKD ($) Language Cantonese, Mandarin and English Time Hong Kong Standard Time (GMT plus 7 hours) TIP Always carry a packet of tissues with you for an emergency.

The Misfit Economy: Lessons in Creativity From Pirates, Hackers, Gangsters and Other Informal Entrepreneurs

by

Alexa Clay

and

Kyra Maya Phillips

Published 23 Jun 2015

THE WORLD OF COPYCAT INNOVATION is not limited to the types of counterfeit consumer goods sold in Chungking Mansions. Since the Internet revolution, with information so readily accessible, products, services, even whole businesses can be cloned and copied with ease. The Berlin-based company Wimdu, for example, is an exact replica of the successful platform Airbnb, a peer-to-peer rental market that provides an alternative to hotels. Wimdu was built by reverse-engineering Airbnb’s functions and borrowing from the site’s look and feel. Illustrating the power of iteration over pure invention, Wimdu created in a matter of months what it had taken Airbnb four years to develop. By June 2011, the company had raised over $90 million.7 Wimdu was started by three now-infamous German brothers—Oliver, Marc, and Alexander Samwer—who have a history of reverse-engineering U.S.

5 Day Weekend: Freedom to Make Your Life and Work Rich With Purpose

by

Nik Halik

and

Garrett B. Gunderson

Published 5 Mar 2018

In this new model, people rent beds, cars, boats, and other assets directly from each other instead of owning things themselves or purchasing them from traditional retailers and service companies. Just as Amazon allows anyone to become a retailer, sharing services lets people act as a taxi service or hotel. At the time of this writing, the consumer peer-to-peer rental market is valued at $26 billion.10 Harvard Business Review argues that the term “sharing economy” is a misnomer and that a more accurate term for it is “access economy.”11 We won’t split hairs. The point we want to make is that this new technology-facilitated model is a great, simple way to leverage your existing assets to earn extra money on the side.

The Internet Is Not the Answer

by

Andrew Keen

Published 5 Jan 2015

No, the Internet is not the answer, especially when it comes to the so-called sharing economy of peer-to-peer networks like Uber and Airbnb. The good news is that, as Wired’s Marcus Wohlsen put it, the “sun is setting on the wild west” of ride- and apartment-sharing networks.44 Tax collectors and municipalities from Cleveland to Hamburg are recognizing that many peer-to-peer rentals and ride-sharing apps are breaking both local and national housing and transportation laws. What the Financial Times calls a “regulatory backlash”45 has pushed Uber to limit surge pricing during emergencies46 and forced Airbnb hosts to install smoke and carbon monoxide detectors in their homes.47 “Just because a company has an app instead of a storefront doesn’t mean consumer protection laws don’t apply,” notes the New York State attorney general Eric Schneiderman, who is trying to subpoena Airbnb’s user data in New York City.48 A group of housing activists in San Francisco is even planning a late 2014 ballot measure in the city that would “severely curb” Airbnb’s operations.49 “Airbnb is bringing up the rent despite what the company says,” explains the New York City–based political party Working Families.50 The answer is to use the law and regulation to force the Internet out of its prolonged adolescence.

Autonomous Driving: How the Driverless Revolution Will Change the World

by

Andreas Herrmann

,

Walter Brenner

and

Rupert Stadler

Published 25 Mar 2018

So far, most sharing models have been station based (A-to-A), i.e. the customers have to drop off the vehicle where they picked it up. However, an increasing number of sharing providers are making their customers a free-floating offer (A-to-B); recent examples are Car2Go and DriveNow [131, 1, 90]. The consumer peer-to-peer rental market alone is valued at $26 billion, with new services and platforms popping up all the time. It has disrupted mature industries such as hotels by providing consumers with convenient and cost-effective access to resources without the financial, emotional or social burdens of ownership. At the same time, ride-sharing models have emerged that are operated for business or private customers as taxi-like services.

European Spring: Why Our Economies and Politics Are in a Mess - and How to Put Them Right

by

Philippe Legrain

Published 22 Apr 2014

One is Paris-based Buzzcar, founded by the founder of Zipcar. Tamyca is a German equivalent. (Whipcar, a British one, closed in 2013.) Still others offer taxi-like services, notably Uber, that can call on additional drivers at peak times. In France, La Machine du Voisin even allows people to rent out the use of their washing machine.555 Such peer-to-peer rental schemes make better use of an economy’s assets, provide extra income for their owners and are often cheaper and more convenient for borrowers. Just find somewhere nearby with your smartphone, check out the reviews and pay online: simple. Or at least it should be. Unfortunately, vested interests and bureaucratic regulation sometimes impede collaborative consumption.