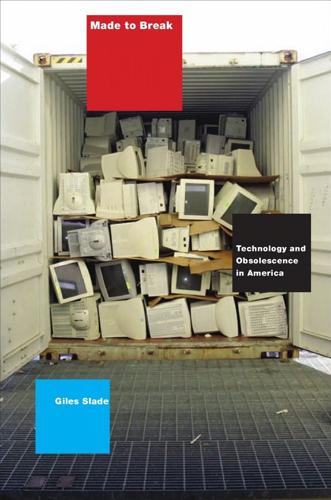

Made to Break: Technology and Obsolescence in America

by

Giles Slade

Published 14 Apr 2006

The Status Seekers (1959) was a groundbreaking examination of America’s social and organizational dynamics, and The Waste Makers (1960) was a highly critical book-length study of planned obsolescence in contemporary American culture. At the appearance of The Hidden Persuaders, as America fell into recession, the debate over planned obsolescence exploded into a national controversy. In 1958 similar criticisms appeared in Galbraith’s Afflu nt Society. By 1959 discussions of planned obsolescence in the conservative pages of the Harvard Business Review created a surge of renewed interest in Packard’s firs book, which had contained numerous observations about planned obsolescence. With the topic now achieving national prominence, Packard wanted to return to it in a book-length study focused specifica ly on waste.

…

Although Brooks Stevens had understood planned obsolescence to mean psychological obsolescence (making consumer goods appear dated through the use of design), Waldheim’s piece, by a committed former teacher of industrial design,explicitly concerned death-dating.It was the magazine’s fina word on the subject of planned obsolescence, a term that appeared in the Design News debate for the firs and only time in Waldheim’s essay. And of course it is significan that Design News chose not to run a piece in favor of planned obsolescence by Milwaukee’s crown prince of obsolescence, Stevens himself. By 1959 planned obsolescence had become a very unpopular business strategy.

…

I am considerably indebted both for her generosity and friendship to the Library of Congress’s gifted reference librarian, Emily Howie, for patiently digging out and photocopying one of the few survival original copies of London’s firs pamphlet. In total, Bernard London wrote three essays: Ending the Depression Through Planned Obsolescence (New York:self-published,1932),2 pp.; The New Prosperity through Planned Obsolescence: Permanent Employment, Wise Taxation and Equitable Distribution of Wealth (New York: self-published, 1934),67 pp.;and Rebuilding a Prosperous Nation through Planned Obsolescence (New York: self-published, 1935), 40 pp. All are available at the Library of Congress. 38. London, Ending the Depression through Planned Obsolescence. 39. Ibid., pp. 6–7. 40. Ibid., p. 12. 41. Ibid., p. 13. 42. Aldous Huxley, Brave New World (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1959), p. 49. 43.

A Life Less Throwaway: The Lost Art of Buying for Life

by

Tara Button

Published 8 Feb 2018

•Feeling close to nature has been shown to decrease materialism, so get out as much as possible, even if you just go into your back garden or a public park. Nature documentaries can also be a lovely way to escape from seeing ‘stuff’. * * * 2 Planned Obsolescence or Why they don’t make ’em like they used to ‘Obsolescence’ is a horrible mouthful of a word that essentially means ‘when something becomes useless’. ‘Planned obsolescence’, therefore, is when people plan for products to become useless. Deliberately. Let that sink in for a second. There are two main ways planned obsolescence happens. The first is physical, where companies design products to break before they need to. That is the subject of this chapter.

…

The other is psychological obsolescence, where people are made to feel that they no longer want the possessions they already have. We’ll look at that in the next chapter. But first I’m going to take you back to the Twenties and Thirties to discover how planned obsolescence came about. I’ll also share with you some of the shocking evidence of companies who have conspired against us to change the way we buy forever. WHO PLANNED IT? Planned obsolescence was born and brought up (to be very naughty) in America. ‘Obsolescence is the American way,’ boasted industrial designers Roy Sheldon and Egmont Arens in their 1932 book Consumer Engineering. And certainly Americans took quickly to the idea of rampantly replacing their possessions, while Europeans still held on to theirs as long as possible.

…

The stock market had crashed and the country was in the middle of what became known as the Great Depression, with millions jobless and around half of all children without decent shelter or food to eat. In these conditions we can’t blame people for clutching at ideas like planned obsolescence to solve the issues, even if we are now left to deal with the fallout. In 1932 a Russian-American called Bernard London published a grand plan entitled ‘Ending the Depression Through Planned Obsolescence’. After noticing that people held onto their products longer in a depression and this meant less money being spent on goods, he suggested that every product, from shoes to cars, houses to hats, be given a set lifespan.

The Day the World Stops Shopping

by

J. B. MacKinnon

Published 14 May 2021

The member companies of Phoebus agreed to depress lamp life to a thousand-hour standard. More than three decades later, in 1960, muckraking journalist Vance Packard popularized the term “planned obsolescence” to describe manufacturers’ deliberate efforts to design products so that they are quickly used up, stop working, fall apart, cannot be fixed, or otherwise become stale-dated. The Phoebus cartel’s decision to shorten bulb lifespans is considered one of the earliest examples of planned obsolescence at an industrial scale. Phoebus is easily cast as a conspiracy of big-business evil-doers. It even makes an appearance as such in Thomas Pynchon’s novel Gravity’s Rainbow, in which the shadowy organization sends an agent in asbestos-lined gloves and seven-inch heels to seize die-hard bulbs that burn beyond their thousandth hour of service.

…

By the late 1920s, the repetitive sales model had become so popular that a leading financier declared obsolescence the “new god” of the American business elite. Advocates for shorter product lifespans could be found across the political spectrum. Giles Slade, in his book Made to Break, traces the term “planned obsolescence” to its roots. The earliest reference he found was in a 1932 pamphlet, “Ending the Depression through Planned Obsolescence,” that promoted short-lived products as beneficial to the working class. In 1936, a similarly themed essay in the magazine Printers’ Ink declared durable products “outmoded” and warned, “If Merchandise Does Not Wear Out Faster, Factories Will Be Idle, People Unemployed.”

…

Many of today’s clothes are not, in any case, made to last: socks and tights that fall apart in a matter of hours, shirts that lose buttons, trousers that tear, sweaters that pill, clothing that shrinks or stains or is ruined at the cleaners, T-shirts that get those tiny, mysterious holes that are a staple of internet threads. (Do I have moths? Bugs? No, you have planned obsolescence. The holes are caused by today’s thin fabrics rubbing at the belt line, against countertops, and what have you.) The ultimate in clothing turnover is the white T-shirt, which is cheaply made, stains easily, and sells poorly in second-hand stores because no one wants to wear your cheap and stained white T-shirt.

Less Is More: How Degrowth Will Save the World

by

Jason Hickel

Published 12 Aug 2020

In fact, in a growth-oriented system, the goal is quite often to avoid satisfying human needs, and even to perpetuate need itself. Once we understand this, it becomes clear that there are huge chunks of the economy that are actively and intentionally wasteful, and which do not serve any recognisable human purpose. Step 1. End planned obsolescence Nowhere is this tendency clearer than when it comes to the practice of planned obsolescence. Companies desperate to increase sales seek to create products that are intended to break down and require replacement after a relatively short period of time. The practice was first developed in the 1920s, when lightbulb manufacturers, led by the US company General Electric, formed a cartel and plotted to shorten the lifespan of incandescent bulbs – from an average of about to 2,500 hours down to 1,000 or even less.3 It worked like a charm.

…

Nylon stockings that are designed to tear after a few wears, devices with new ports that render old dongles and chargers useless – everyone has stories about the absurdities of planned obsolescence. IKEA became a multi-billion-dollar empire in large part by inventing furniture that is effectively disposable. Whole swathes of Scandinavia’s forests have been churned into cheap tables and shelving units that are designed for the dump. There’s a paradox here. We like to think of capitalism as a system that’s built on rational efficiency, but in reality it is exactly the opposite. Planned obsolescence is a form of intentional inefficiency. The inefficiency is (bizarrely) rational in terms of maximising profits, but from the perspective of human need, and from the perspective of ecology, it is madness: madness in terms of the resources it wastes, and madness in terms of the needless energy it consumes.

…

Instead of mindlessly pursuing growth in every sector, whether or not we actually need it, we can decide what kinds of things we want to grow (sectors like clean energy, public healthcare, essential services, regenerative agriculture – you name it), and what sectors need to radically degrow (things like fossil fuels, private jets, arms and SUVs). We can also scale down the parts of the economy that are designed purely to maximise profits rather than to meet human needs, like planned obsolescence, where products are made to break down after a short time, or advertising strategies intended to manipulate our emotions and make us feel that what we have is inadequate. As we liberate people from the toil of unnecessary labour, we can shorten the working week to maintain full employment, distribute income and wealth more fairly, and invest in public goods like universal healthcare, education and affordable housing.

The Story of Stuff: The Impact of Overconsumption on the Planet, Our Communities, and Our Health-And How We Can Make It Better

by

Annie Leonard

Published 22 Feb 2011

And a glut would be very bad for business indeed. So the architects of the system came up with a strategy to keep consumers buying: planned obsolescence. Another name for planned obsolescence is “designed for the dump.” Brooks Stevens, an American industrial designer who is widely credited with popularizing the term in the 1950s, defined it as “instilling in the buyer the desire to own something a little newer, a little better, a little sooner than is necessary.”55 In planned obsolescence, products are intended to be thrown away as quickly as possible and then replaced. (That’s called “shortening the replacement cycle.”)

…

Today’s cell phones, for example, which have an average life span of only about a year, are pretty much never technologically obsolete when we throw them away and replace them with new ones. That’s planned obsolescence at work. The idea of planned obsolescence gained currency in the 1920s and 30s as government and businesspeople realized that our industries were making more Stuff than people cared to, or could afford to, buy. In 1932, a real estate broker named Bernard London who wanted to play his part in stimulating the economy distributed his now infamous pamphlet called Ending the Depression through Planned Obsolescence. In it London argued for creating a government agency tasked with assigning death dates to specific consumer products, at which time consumers would be required to turn the Stuff in for replacements, even if they still worked fine.

…

Now, not every lousy thing that industry has done was intentional and manipulative, but this one was. Corporate decision makers, industrial designers, economic planners, and advertising men actively, strategically promoted planned obsolescence as a way to keep the engine of the economy running. In his 1960 book The Waste Makers (one of my all time favorite reads), social critic Vance Packard documents the early debates about planned obsolescence in consumer products in the 1950s and 60s. While some individuals opposed the idea, worrying that it was unethical and jeopardized their professional credibility, others recognized it as a way to ensure never-ending markets for all the Stuff they designed, produced, and advertised—and they embraced it wholeheartedly.

Wasteland: The Dirty Truth About What We Throw Away, Where It Goes, and Why It Matters

by

Oliver Franklin-Wallis

Published 21 Jun 2023

This is partly good old-fashioned nostalgia, but it’s also something real, intuited in our everyday lives and easily proven in any junkyard or landfill. Goods cheaply bought are cheaply made – no surprise there. But when it comes to e-waste, that sense is often followed by another, more serious allegation: that of ‘planned obsolescence’, by which industries design products with artificially short lives, so that they need to be replaced more quickly. Planned obsolescence is often treated as some kind of conspiracy, when in reality it is just a historical fact. The idea first gained traction as early as the 1920s, when manufacturers were coming up with means to convince people to upgrade to newer models.

…

CONTROL, DELETE 1 Vanessa Forti, Cornelis Peter Baldé et al., The Global E-waste Monitor 2020: Quantities, flows, and the circular economy potential, United Nations University and United Nations Institute for Training and Research, 2020. 2 Simon O’Dea, ‘Number of smartphones sold to end users worldwide from 2007 to 2021 (in million units)’, Statista, 06/05/2022 (accessed: 24/06/2022): https://www.statista.com/statistics/263437/global-smartphone-sales-to-end-users-since-2007/ 3 ‘Global PC shipments pass 340 million in 2021 and 2022 is set to be even stronger’, Canalys, 12/01/2022: https://www.canalys.com/newsroom/global-pc-market-Q4-2021 4 Saranraj Mathivanan, ‘Global Headphones Market Shipped nearly 550 million units in 2021’, Futuresource Consulting (2022): https://www.futuresource-consulting.com/insights/global-headphones-market-shipped-nearly-550-million-units-in-2021 5 Calculated using Apple, ‘Environmental Responsibility Report: 2019 Progress Report, covering fiscal year 2018’, 2019: https://www.apple.com/environment/pdf/Apple_Environmental_Responsibility_Report_2019.pdf 6 Bianca Nogrady, ‘Your old phone is full of untapped precious metals’, BBC Future, 18/10/2016: https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20161017-your-old-phone-is-full-of-precious-metals 7 Adam Minter, Junkyard Planet: Travels in the Billion-Dollar Trash Trade (New York: Bloomsbury Press), 2013, p. 175. 8 World Economic Forum, ‘A New Circular Vision for Electronics: Time For A Global Reboot’, 2019, p. 5. 9 Lauren Joseph and James Pennington, ‘Tapping the economic value of e-waste’, China Daily, 29/10/2018: http://europe.chinadaily.com.cn/a/201810/29/WS5bd64e5aa310eff3032850ac.html 10 World Economic Forum, ‘A New Circular Vision’, p. 11. 11 Or $57 billion, according to Forti, Baldé et al., The Global E-waste Monitor 2020. 12 Originally, the company was called Computer Recyclers of America, but it rebranded and relaunched in 2005 as ERI. 13 ‘Nonferrous Scrap Terminology’, Recycling Today, 15/07/2001: https://www.recyclingtoday.com/article/nonferrous-scrap-terminology/ 14 Richard Pallot, ‘Amazon destroying millions of items of unsold stock in one of its UK warehouses every year, ITV News investigation finds’, ITV News, 21/06/2021: https://www.itv.com/news/2021-06-21/amazon-destroying-millions-of-items-of-unsold-stock-in-one-of-its-uk-warehouses-every-year-itv-news-investigation-finds 15 Thomas Claburn, ‘Apple seeks damages from recycling firm that didn’t damage its devices: 100,000 iThings “resold” rather than broken up as expected’, The Register, 05/10/2020. 16 ‘Burberry burns bags, clothes and perfume worth millions’, BBC News, 19/07/2018: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-44885983 17 Christine Frederick, Selling Mrs. Consumer (New York: Business Bourse), 1929, p. 246. I first read this quoted in Susan Strasser, Waste and Want (New York: Henry Holt and Company), 1999, p. 197. 18 Bernard London, Ending the Depression Through Planned Obsolescence (1932): https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/27/London_%281932%29_Ending_the_depression_through_planned_obsolescence.pdf 19 Giles Slade, Made to Break: Technology and Obsolescence in America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press), 2006, p. 32. 20 Victor Lebow, Journal of Retailing (Spring 1955), p. 7; cited in Vance Packard, The Waste Makers (New York: iG Publishing), 1960, p. 38. 21 J.

…

Corporations previously incentivised to produce high-quality products that lasted as long as possible were now lured into producing cheaper goods in ever greater volume, knowing that the consequences would fall not on their bottom line, but on the consumer. Along the way, the booming marketing industry gave us the concept of ‘planned obsolescence’, in which new products were designed to fail and thus need replacing – culminating in our modern world, where technology from smartphones to tractors can in many cases no longer be repaired without voiding the manufacturer’s warranty. Today, one third of what we throw away is something produced the same year; and between 1960 and 2010, the amount of waste the average American was creating every year tripled.17 The modern economy is built on trash.

Death Glitch: How Techno-Solutionism Fails Us in This Life and Beyond

by

Tamara Kneese

Published 14 Aug 2023

When they die from unsafe working conditions or from Covid-19 complications, their families are left without life insurance payouts or legal recourse. The tech companies that manage workers through algorithms determine what happens to people’s aggregated data and have the potential to affect postmortem legacies as well. Platforms built for real-time tracking and engagement, and devices designed with planned obsolescence, are imperfect vessels for digital immortality. Digital remains are accidentally dependent on the same platform infrastructures that are their very undoing. Memorialization thus marks a departure from the intended uses of social media. In short, death disrupts social media. This is not just a cheeky reference to Silicon Valley’s rhetoric of disruption as a way of remaking and monetizing the mundane through innovation.

…

Ray Kurzweil, the famous transhumanist who is currently a director of engineering at Google (a figurehead position but revealing of Google’s values, nonetheless), believes that AI has the ability to solve all of the earth’s problems, including climate change. The temporal patterns of the Singularity thus coincide with Silicon Valley’s race for the new—that is, the planned obsolescence of products, perpetual updates and upgrades of software packages, or the fetishization of newness. As I learned by attending the 2012 Singularity Summit in San Francisco, some transhumanists argue that physiological death itself is a disease that can and should be cured. For some futurists, transhumanism is a form of spiritual practice or an entire cosmology.76 Their belief in data exceeds their pragmatism, and they believe that when used correctly, data can enable humans to live forever.

…

As a result of this disconnect between personalized design and collective use, once they lose their smartness and use-value, obsolete high-tech objects may inconvenience kin members who cannot make sense of their preprogrammed settings.9 Smart homes facilitate routine and, in theory, allow a person’s preferences to continue in perpetuity. But the planned obsolescence of digital technologies means that once-smart objects quickly become refuse.10 Despite their ghostly resonances, digital remains cannot be separated from the material culture they are tied to. First, I delineate the history of smart technologies, particularly as they relate to home settings.

The Capitalist Manifesto

by

Johan Norberg

Published 14 Jun 2023

I don’t rule out that there are real examples of planned obsolescence, where the manufacturer actively reduces the longevity of a product, but it is more unusual than the debate suggests and the company that is exposed doing it will quickly be punished in the market. France has a law against planned obsolescence, and it has mostly shown how difficult it is to document a single case. Yes, it was heard all over the world that Apple was forced to pay a fine after older iPhones started working more slowly following a software update. But what few observed is that Apple was never considered guilty of planned obsolescence, only of not informing users of the change.

…

(Although I am embarrassed to say that books by classical liberals like Locke and Mill seem to be particularly prone to being stolen.)14 Undignified consumption Several critics of In Defence of Global Capitalism said I ignored the fact that one form of fraud underlines the entire modern consumer society. It concerns so-called ‘planned obsolescence’, companies that deliberately build in errors and shortcomings that shorten the lifespan of products and therefore force us to buy new ones. According to some critics, it is a central mechanism behind the modern growth model.15 Isn’t it strange that older iPhones suddenly started to slow down after a software update?

…

It is not commercialism – it is us: ‘I can say categorically that the people of all the cultures I have come in contact with exhibit a strong desire to have the benefits of industrial goods that are available. I am convinced that the “nonmaterialistic culture” is a myth.’18 In this consumption we can also discern a certain restlessness that is not due to planned obsolescence but because it is deeply human to get used to an item and then be attracted by something new. There is no big brand running expensive campaigns to make us tired of old personal names and buy a new, fresh one that they have patented. Still, there are extremely strong fashion trends in the names we give our children.

The Dark Cloud: How the Digital World Is Costing the Earth

by

Guillaume Pitron

Published 14 Jun 2023

See ‘China said to study IBM servers for bank security risks’, Bloomberg, 28 May 2014. 41 ‘US telcos ordered to “rip and replace” Huawei components’, bbc.com, 11 December 2020. 42 ‘Bouygues to remove 3,000 Huawei mobile antennas in France by 2028’, Reuters, 27 August 2020. 43 ‘The data center is dead’, Gartner, 26 July 2018. 44 ‘Sonos will stop providing software updates for its oldest products in May’, The Verge, 21 January 2020. 45 Interview with Adèle Chasson, corporate campaigner of the HOP (Stop Planned Obsolescence) association in 2020. According to research conducted in 2021 by the German institute Fraunhofer, 20 per cent of smartphones are no longer used because of software issues. Read ‘Ecodesign preparatory study on mobile phones, smartphones and tablets’, Fraunhofer for the European Commission, February 2021. 46 Frédéric Bordage, Sobriété numérique, les clés pour agir [‘Digital sobriety, the keys for action’], op. cit. 47 Frédéric Bordage, ‘Logiciel : la clé de l’obsolescence programmée du matériel informatique’ [‘Software: the key to planned obsolescence of IT equipment’], GreenIT.fr, 24 May 2010. 48 ‘White Paper on the Digital Economy and the Environment’, op. cit. 49 ‘Working with microbes to clean up electronic waste’, Next Nature Network, 8 March 2021. 50 Robert M.

…

The ecological gain is massive, considering that a third of the food produced on Earth is thrown away, representing a sizeable 8 per cent of carbon emissions. And that’s not all, since digital technologies ‘help to integrate goods into sharing systems [such as loans and cash gifts between individuals]’, ‘facilitate crowdfunding for renewables or agroecology […]’, and are ‘helping to combat planned obsolescence, such as Spareka, a platform selling spare parts connected to a community of repairers’, states the same leading report.30 In a time of fake news and alternative facts, never have we had such accurate information with which to improve our understanding of the world. This is attributable to the engineering behind digital technologies, for one smartphone alone is more powerful than all the information systems used to send a man to the Moon.31 Now multiply these tools by the number of humans on Earth, picture the legions of super calculators capable of executing billions of operations per second, and you have a new gospel: ‘Green IT’.

…

And this is not the exclusive domain of China: fearing espionage operations, the US mobilised nearly $2 billion at the end of 2020 in order to ‘rip and replace’ all communication and video-surveillance equipment installed on American soil by Chinese companies.41 Several European countries followed suit for the same reason, and announced that they, too, would rid their territory of thousands of Huawei 5G antennas.42 This junking of equipment, while the result of political decisions, remind us of manufacturing strategies of planned obsolescence, aimed at speeding up a product’s demise. Such obsolescence can be ‘material’, whereby a component of a smartphone — more often than not, its battery — stops working or is impossible to replace because it is glued fast to the rest of the device, condemning the entire smartphone to the scrap heap.

Subscribed: Why the Subscription Model Will Be Your Company's Future - and What to Do About It

by

Tien Tzuo

and

Gabe Weisert

Published 4 Jun 2018

Whether it’s GE, Amazon, or Uber, they are all succeeding because they recognized that we now live in a digital world, and in this new world, customers are different. The way people buy has changed for good. We have new expectations as consumers. We prefer outcomes over ownership. We prefer customization, not standardization. And we want constant improvement, not planned obsolescence. We want a new way to engage with business. We want services, not products. The one-size-fits-all approach isn’t going to cut it anymore. And to succeed in this new digital world, companies have to transform. THE PRODUCT ERA AND THE TYRANNY OF THE MARGIN For the past 120 or so years, we’ve been living in a product economy.

…

Model Ts came only in black because with one automobile coming off the line every three minutes, that was the only color that would dry fast enough. Then once these big companies established market share, the thinking went, they could start to gently raise their prices and make money off the difference, or margin. The margin ruled everything (and a little planned obsolescence never hurt). It’s difficult to overstate the power that big postwar American corporations had. They organized themselves around strictly delineated product divisions and didn’t have to answer to anyone. There were no call centers, no customer service reps, and, in many cases, no returns, period.

…

CHAPTER 12 SALES: THE EIGHT NEW GROWTH STRATEGIES We’ve all bought something that doesn’t work out—that gizmo that sits in the closet for a few years before it gets donated or just thrown into the trash. Maybe it looked cool in the ad. Maybe you used it once or twice, and then the novelty wore off. Maybe there’s some planned obsolescence that you can’t be bothered to fix. Or maybe there are some things that you buy automatically, that you don’t really think about, because you’ve seen the billboards and the TV ads and the display stands, and when you walk into the store some basic Madison Avenue psychology takes over, and you buy it.

Affluenza: The All-Consuming Epidemic

by

John de Graaf

,

David Wann

,

Thomas H Naylor

and

David Horsey

Published 1 Jan 2001

As women try on perfumes in an upscale department store, the narrator continues: “Our egos are best nourished by a well-placed investment in real luxury goods—what you might call discreetly conspicuous waste.”2 “Waste not, want not,” Benjamin Franklin once admonished. But the new slogan might have been Waste More, Want More. Almost overnight, the good life became the goods life. PLANNED OBSOLESCENCE “The immediate postwar period does represent a huge change in the kinds of attitudes that Americans have had about consumption,” says historian Susan Strasser, the author of Satisfaction Guaranteed.3 “Discreetly conspicuous waste” got another boost from what marketers called “planned obsolescence.” Products were made to last only a short time so that they would have to be replaced frequently (adding to sales), or they were continually upgraded, more commonly in style than in quality.

…

“We start looking at other people and saying that if they don’t give us pleasure, they are disposable. I think the trend is dangerous, and I think we need to have old values where we live in the same house as long as we can, where we keep material items as long as we can, and where we be faithful to each other.” In the use-it-once-and-throw-it-away, planned-obsolescence world of American consumer culture, it should not be surprising that attitudes formed in relation to products eventually get transferred to people as well. Out of sight, out of mind. Moreover, family life strains under the stress of excess. As both parents work full time and more to meet their swelling expectations of the good life, then rush to maintain the frenetic lifestyles those expectations demand, nerves are frayed and tempers boil.

…

Conservative economist Wilhelm Ropke feared that “we neglect to include in the calculation of these potential gains in the supply of material goods the possible losses of a non-material kind.”10 Centrist Vance Packard lambasted advertising (The Hidden Persuaders, 1957), keeping up with the Joneses (The Status Seekers, 1959) and planned obsolescence (The Waste Makers, 1960). And the liberal John Kenneth Galbraith suggested that a growing economy fulfilled needs it created itself, leading to no improvement in happiness. Our emphasis on “private opulence,” he said, led to “public squalor"—declining transit systems, schools, parks, libraries, and air and water quality.

The Elements of Power: Gadgets, Guns, and the Struggle for a Sustainable Future in the Rare Metal Age

by

David S. Abraham

Published 27 Oct 2015

“Apple’s Latest ‘Innovation’ Is Turning Planned Obsolescence into Planned Failure,” iFixit Blog, January 20, 2011, accessed December 19, 2014, www.ifixit.com/blog/2011/01/20/apples-latest-innovation-is-turning-planned-obsolescence-into-planned-failure/; Apple, “iPhone Support—Screen Damage,” iPhone Screen Damage Repair, accessed May 19, 2014, https://www.apple.com/support/iphone/repair/screen-damage/; Brian Clark Howard, “Planned Obsolescence: 8 Products Designed to Fail,” Popular Mechanics, accessed December 19, 2014, www.popularmechanics.com/technology/planned-obsolescence-460210#slide-8. T-Mobile plans allow phone upgrades every six months as of January 2014.

…

See also Geopolitics Permanent magnets, 3, 18–22, 25–28, 141, 237n21, 268n14, 296n26, 297n33 Perskovites, 296n26 Personal consumption, increase in, 215 Peru, illegal mining in, 112 Philips Corporation, 110 Phillips, Jeff, 56, 61–62 Phones: iPhones, 1–3, 10 mobile phones, 120–21, 179, 187, 260n14 rare metals in, 27 recycling of, 224 smartphones, 121, 216, 218, 260n15 Pietrobono, Amber, 120 Planes, 128–31, 155–60, 168, 274n6, 279n33 Planned obsolescence, 216 Platinum group metals, 144–45, 178, 186, 249n13 PlayStation 2, 131 Political unrest, 48. See also Conflicts, funding of, from rare metals production Politico, on military supply lines, 167 Pollution, 153, 173–77, 181, 182–83. See also Carbon emissions Post-consumer recycling, 186–87 Potvin, J.

Frugal Innovation: How to Do Better With Less

by

Jaideep Prabhu Navi Radjou

Published 15 Feb 2015

The more complex its design, the more costly it is to build, sell and service a product. This in turn makes the product more expensive for the customer to buy, use and maintain. Furthermore, products are designed with planned obsolescence, forcing customers continually to upgrade – an expensive proposition at best. Mobile phones, for instance, are designed to make them hard to disassemble. This complexity and planned obsolescence is a cost to customers and increases environmental waste. Cramming cars with more microchips, for instance, makes them heavier and less fuel efficient. Similarly, American consumers typically replace their mobile phones every two years, which may cheer up Apple and mobile operators, but 125 million obsolete phones end up in landfills every year as a result.

…

Designers should always ask how they can encourage good and deter bad behaviour in users. They should also make sure that customers are repeatedly informed about how they can make better decisions. Design for longevity, not obsolescence Consumer electronics are often designed to be replaced every few months or, at most, every couple of years. Such so-called planned obsolescence is a major contributor to the 20–50 million tonnes of e-waste produced annually worldwide (a volume that is growing at 8% a year). The same applies to consumer durables such as cars, washing machines and some industrial products. To help reduce waste, R&D teams must design longer-lasting products, for which even cost-conscious customers would be willing to pay.

…

MacArthur Foundation 14 John Deere 67 John Lewis 195 Johnson & Johnson 100, 111 Johnson, Warren 98 Jones, Don 112 jugaad (frugal ingenuity) 199, 202 Jugaad Innovation (Radjou, Prabhu and Ahuja, 2012) xvii, 17 just-in-time design 33–4 K Kaeser, Joe 217 Kalanick, Travis 163 Kalundborg (Denmark) 160 kanju 201 Karkal, Shamir 124 Kaufman, Ben 50–1, 126 Kawai, Daisuke 29–30 Kelly, John 199–200 Kennedy, President John 138 Kenya 57, 200–1 key performance indicators see KPIs Khan Academy 16–17, 113–14, 164 Khan, Salman (Sal) 16–17, 113–14 Kickstarter 17, 48, 137, 138 KieranTimberlake 196 Kimberly-Clark 25, 145 Kingfisher 86–7, 91, 97, 157, 158–9, 185–6, 192–3, 208 KissKissBankBank 17, 137 Knox, Steve 145 Knudstorp, Jørgen Vig 37, 68, 69 Kobori, Michael 83, 100 KPIs (key performance indicators) 38–9, 67, 91–2, 185–6, 208 Kuhndt, Michael 194 Kurniawan, Arie 151–2 L La Chose 108 La Poste 92–3, 157 La Ruche qui dit Oui 137 “labs on a chip” 52 Lacheret, Yves 173–5 Lada 1 laser cutters 134, 166 Laskey, Alex 119 last-mile challenge 57, 146, 156 L’Atelier 168–9 Latin America 161 lattice organisation 63–4 Laury, Véronique 208 Laville, Elisabeth 91 Lawrence, Jamie 185, 192–3, 208 LCA (life-cycle assessment) 196–7 leaders 179, 203–5, 214, 217 lean manufacturing 192 leanness 33–4, 41, 42, 170, 192 Learnbox 114 learning by doing 173, 179 learning organisations 179 leasing 123 Lee, Deishin 159 Lego 51, 126 Lego Group 37, 68, 69, 144 Legrand 157 Lenovo 56 Leroy, Adolphe 127 Leroy Merlin 127–8 Leslie, Garthen 150–1 Lever, William Hesketh 96 Levi Strauss & Co 60, 82–4, 100, 122–3 Lewis, Dijuana 212 life cycle of buildings 196 see also product life cycle life-cycle assessment (LCA) 196–7 life-cycle costs 12, 24, 196 Lifebuoy soap 95, 97 lifespan of companies 154 lighting 32, 56, 123, 201 “lightweighting” 47 linear development cycles 21, 23 linear model of production 80–1 Link 131 littleBits 51 Livi, Daniele 88 Livi, Vittorio 88 local communities 52, 57, 146, 206–7 local markets 183–4 Local Motors 52, 129, 152 local solutions 188, 201–2 local sourcing 51–2, 56, 137, 174, 181 localisation 56, 137 Locavesting (Cortese, 2011) 138 Logan car 2–3, 12, 179, 198–9 logistics 46, 57–8, 161, 191, 207 longevity 121, 124 Lopez, Maribel 65–6 Lopez Research 65–6 L’Oréal 174 Los Alamos National Laboratory 170 low-cost airlines 60, 121 low-cost innovation 11 low-income markets 12–13, 161, 203, 207 Lowry, Adam 81–2 M m-health 109, 111–12 M-KOPA 201 M-Pesa 57, 201 M3D 48, 132 McDonough Braungart Design Chemistry (MBDC) 84 McDonough, William 82 McGregor, Douglas 63 MacGyvers 17–18, 130, 134, 167 McKelvey, Jim 135 McKinsey & Company 81, 87, 209 mainstream, frugal products in 216 maintenance 66, 75, 76, 124, 187 costs 48–9, 66 Mainwaring, Simon 8 Maistre, Christophe de 187–8, 216 Maker Faire 18, 133–4 Maker platform 70 makers 18, 133–4, 145 manufacturing 20th-century model 46, 55, 80–1 additive 47–9 continuous 44–5 costs 47, 48, 52 decentralised 9, 44, 51–2 frugal 44–54 integration with logistics 57–8 new approaches 50–4 social 50–1 subtractive method 48 tools for 47, 47–50 Margarine Unie 96 market 15, 28, 38, 64, 186, 189, 192 R&D and 21, 26, 33, 34 market research 25, 61, 139, 141 market share 100 marketing 21–2, 24, 36, 61–3, 91, 116–20, 131, 139 and R&D 34, 37, 37–8 marketing teams 143, 150 markets 12–13, 42, 62, 215 see also emerging markets Marks & Spencer (M&S) 97, 215 Plan A 90, 156, 179–81, 183–4, 186–7, 214 Marriott 140 Mars 57, 158–9, 161 Martin Marietta 159 Martin, Tod 154 mass customisation 9, 46, 47, 48, 57–8 mass market 189 mass marketing 21–2 mass production 9, 46, 57, 58, 74, 129, 196 Massachusetts Institute of Technology see MIT massive open online courses see MOOCs materials 3, 47, 48, 73, 92, 161 costs 153, 161, 190 recyclable 74, 81, 196 recycled 77, 81–2, 83, 86, 89, 183, 193 renewable 77, 86 repurposing 93 see also C2C; reuse Mayhew, Stephen 35, 36 Mazoyer, Eric 90 Mazzella, Frédéric 163 MBDC (McDonough Braungart Design Chemistry) 84 MDI 16 measurable goals 185–6 Mechanical Engineer Laboratory (MEL) 52 “MEcosystems” 154–5, 156–8 Medicare 110 medication 111–12 Medicity 211 MedStartr 17 MEL (Mechanical Engineer Laboratory) 52 mental models 2, 193–203, 206, 216 Mercure 173 Merlin, Rose 127 Mestrallet, Gérard 53, 54 method (company) 81–2 Mexico 38, 56 Michelin 160 micro-factories 51–2, 52, 66, 129, 152 micro-robots 52 Microsoft 38 Microsoft Kinect 130 Microsoft Word 24 middle classes 197–8, 216 Migicovsky, Eric 137–8 Mikkiche, Karim 199 millennials 7, 14, 17, 131–2, 137, 141, 142 MindCET 165 miniaturisation 52, 53–4 Mint.com 125 MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) 44–5, 107, 130, 134, 202 mobile health see m-health mobile phones 24, 32, 61, 129–30, 130, 168, 174 emerging market use 198 infrastructure 56, 198 see also smartphones mobile production units 66–7 mobile technologies 16, 17, 103, 133, 174, 200–1, 207 Mocana 151 Mochon, Daniel 132 modular design 67, 90 modular production units 66–7 Modularer Querbaukasten see MQB “mompreneurs” 145 Mondelez 158–9 Money Dashboard 125 Moneythink 162 monitoring 65–6, 106, 131 Monopoly 144 MOOCs (massive open online courses) 60, 61, 112, 113, 114, 164 Morieux, Yves 64 Morocco 207 Morris, Robert 199–200 motivation, employees 178, 180, 186, 192, 205–8 motivational approaches to shaping consumer behaviour 105–6 Motorola 56 MQB (Modularer Querbaukasten) 44, 45–6 Mulally, Alan 70, 166 Mulcahy, Simon 157 Mulliez family 126–7 Mulliez, Vianney 13, 126 multi-nodal innovation 202–3 Munari, Bruno 93 Murray, Mike 48–9 Musk, Elon 172 N Nano car 119, 156 National Geographic 102 natural capital, loss of 158–9 Natural Capital Leaders Platform 158–9 natural resources 45, 86 depletion 7, 72, 105, 153, 158–9 see also resources NCR 55–6 near-shoring 55 Nelson, Simon 113 Nemo, Sophie-Noëlle 93 Nest Labs 98–100, 103 Nestlé 31, 44, 68, 78, 94, 158–9, 194, 195 NetPositive plan 86, 208 networking 152–3, 153 new materials 47, 92 New Matter 132 new technologies 21, 27 Newtopia 32 next-generation customers 121–2 next-generation manufacturing techniques 44–6, 46–7 see also frugal manufacturing Nigeria 152, 197–8 Nike 84 NineSigma 151 Nissan 4, 4–5, 44, 199 see also Renault-Nissan non-governmental organisations 167 non-profit organisations 161, 162, 202 Nooyi, Indra 217 Norman, Donald 120 Norris, Greg 196 North American companies 216–17 North American market 22 Northrup Grumman 68 Norton, Michael 132 Norway 103 Novartis 44–5, 215 Novotel 173, 174 nudging 100, 108, 111, 117, 162 Nussbaum, Bruce 140 O O2 147 Obama, President Barack 6, 8, 13, 134, 138, 208 obsolescence, planned 24, 121 offshoring 55 Oh, Amy 145 Ohayon, Elie 71–2 Oliver Wyman 22 Olocco, Gregory 206 O’Marah, Kevin 58 on-demand services 39, 124 online communities 31, 50, 61, 134 online marketing 143 online retailing 60, 132 onshoring 55 Opel 4 open innovation 104, 151, 152, 153, 154 open-source approach 48, 129, 134, 135, 172 open-source hardware 51, 52, 89, 130, 135, 139 open-source software 48, 130, 132, 144–5, 167 OpenIDEO 142 operating costs 45, 215 Opower 103, 109, 119 Orange 157 Orbitz 173 organisational change 36–7, 90–1, 176, 177–90, 203–8, 213–14, 216 business models 190–3 mental models 193–203 organisational culture 36–7, 170, 176, 177–9, 213–14, 217 efficacy focus 181–3 entrepreneurial 76, 173 see also organisational change organisational structure 63–5, 69 outsourcing 59, 143, 146 over-engineering 27, 42, 170 Overby, Christine 25 ownership 9 Oxylane Group 127 P P&G (Procter & Gamble) 19, 31, 58, 94, 117, 123, 145, 195 packaging 57, 96, 195 Page, Larry 63 “pain points” 29, 30, 31 Palmer, Michael 212 Palo Alto Junior League 20 ParkatmyHouse 17, 63, 85 Parker, Philip 61 participation, customers 128–9 partner ecosystems 153, 154, 200 partners 65, 72, 148, 153, 156–8 sharing data with 59–60 see also distributors; hyper-collaboration; suppliers Partners in Care Foundation 202 partnerships 41, 42, 152–3, 156–7, 171–2, 174, 191 with SMBs 173, 174, 175 with start-ups 20, 164–5, 175 with suppliers 192–3 see also hyper-collaboration patents 171–2 Payne, Alex 124 PE International 196 Pearson 164–5, 167, 181–3, 186, 215 Pebble 137–8 peer-to-peer economic model 10 peer-to-peer lending 10 peer-to-peer sales 60 peer-to-peer sharing 136–7 Pélisson, Gérard 172–3 PepsiCo 38, 40, 179, 190, 194, 215 performance 47, 73, 77, 80, 95 of employees 69 Pernod Ricard 157 personalisation 9, 45, 46, 48, 62, 129–30, 132, 149 Peters, Tom 21 pharmaceutical industry 13, 22, 23, 33, 58, 171, 181 continuous manufacturing 44–6 see also GSK Philippines 191 Philips 56, 84, 100, 123 Philips Lighting 32 Picaud, Philippe 122 Piggy Mojo 119 piggybacking 57 Piketty, Thomas 6 Plan A (M&S) 90, 156, 179–81, 183–4, 186–7, 214 Planet 21 (Accor) 174–5 planned obsolescence 24, 121 Plastyc 17 Plumridge, Rupert 18 point-of-sale data 58 Poland 103 pollution 74, 78, 87, 116, 187, 200 Polman, Paul 11, 72, 77, 94, 203–5, 217 portfolio management tools 27, 33 Portugal 55, 103 postponement 57–8 Potočnik, Janez 8, 79 Prabhu, Arun 25 Prahalad, C.K. 12 predictive analytics 32–3 predictive maintenance 66, 67–8 Priceline 173 pricing 81, 117 processes digitising 65–6 entrenched 14–16 re-engineering 74 simplifying 169, 173 Procter & Gamble see P&G procurement priorities 67–8 product life cycle 21, 75, 92, 186 costs 12, 24, 196 sustainability 73–5 product-sharing initiatives 87 production costs 9, 83 productivity 49, 59, 65, 79–80, 153 staff 14 profit 14, 105 Progressive 100, 116 Project Ara 130 promotion 61–3 Propeller Health 111 prosumers xix–xx, 17–18, 125, 126–33, 136–7, 148, 154 empowering and engaging 139–46 see also horizontal economy Protomax 159 prototypes 31–2, 50, 144, 152 prototyping 42, 52, 65, 152, 167, 192, 206 public 50–1, 215 public sector, working with 161–2 publishers 17, 61 Pullman 173 Puma 194 purchasing power 5–6, 216 pyramidal model of production 51 pyramidal organisations 69 Q Qarnot Computing 89 Qualcomm 84 Qualcomm Life 112 quality 3, 11–12, 15, 24, 45, 49, 82, 206, 216 high 1, 9, 93, 198, 216 measure of 105 versus quantity 8, 23 quality of life 8, 204 Quicken 19–21 Quirky 50–1, 126, 150–1, 152 R R&D 35, 67, 92, 151 big-ticket programmes 35–6 and business development 37–8 China 40, 188, 206 customer focus 27, 39, 43 frugal approach 12, 26–33, 82 global networks 39–40 incentives 38–9 industrial model 2, 21–6, 33, 36, 42 market-focused, agile model 26–33 and marketing 34, 37, 37–8 recommendations for managers 34–41 speed 23, 27, 34, 149 spending 15, 22, 23, 28, 141, 149, 152, 171, 187 technology culture 14–15, 38–9 see also Air Liquide; Ford; GSK; IBM; immersion; Renault; SNCF; Tarkett; Unilever R&D labs 9, 21–6, 70, 149, 218 in emerging markets 40, 188, 200 R&D teams 26, 34, 38–9, 65, 127, 150, 194–5 hackers as 142 innovation brokering 168 shaping customer behaviour 120–2 Raspberry Pi 135–6, 164 Ratti, Carlo 107 raw materials see materials real-time demand signals 58, 59 Rebours, Christophe 157–8 recession 5–6, 6, 46, 131, 180 Reckitt Benckiser 102 recommendations for managers flexing assets 65–71 R&D 34–41 shaping consumer behaviour 116–24 sustainability 90–3 recruiting 70–1 recyclable materials 74, 81, 196 recyclable products 3, 73, 159, 195–6 recycled materials 77, 81–2, 83, 86, 89, 183, 193 recycling 8, 9, 87, 93, 142, 159 e-waste 87–8 electronic and electrical goods (EU) 8, 79 by Tarkett 73–7 water 83, 175 see also C2C; circular economy Recy’Go 92–3 regional champions 182 regulation 7–8, 13, 78–9, 103, 216 Reich, Joshua 124 RelayRides 17 Renault 1–5, 12, 117, 156–7, 179 Renault-Nissan 4–5, 40, 198–9, 215 renewable energy 8, 53, 74, 86, 91, 136, 142, 196 renewable materials 77, 86 Replicator 132 repurposing 93 Requardt, Hermann 189 reshoring 55–6 resource constraints 4–5, 217 resource efficiency 7–8, 46, 47–9, 79, 190 Resource Revolution (Heck, Rogers and Carroll, 2014) 87–8 resources 40, 42, 73, 86, 197, 199 consumption 9, 26, 73–7, 101–2 costs 78, 203 depletion 7, 72, 105, 153, 158–9 reducing use 45, 52, 65, 73–7, 104, 199, 203 saving 72, 77, 200 scarcity 22, 46, 72, 73, 77–8, 80, 158–9, 190, 203 sharing 56–7, 159–61, 167 substitution 92 wasting 169–70 retailers 56, 129, 214 “big-box” 9, 18, 137 Rethink Robotics 49 return on investment 22, 197 reuse 9, 73, 76–7, 81, 84–5, 92–3, 200 see also C2C revenues, generating 77, 167, 180 reverse innovation 202–3 rewards 37, 178, 208 Riboud, Franck 66, 184, 217 Rifkin, Jeremy 9–10 robots 47, 49–50, 70, 144–5, 150 Rock Health 151 Rogers, Jay 129 Rogers, Matt 87–8 Romania 2–3, 103 rookie mindset 164, 168 Rose, Stuart 179–80, 180 Roulin, Anne 195 Ryan, Eric 81–2 Ryanair 60 S S-Oil 106 SaaS (software as a service) 60 Saatchi & Saatchi 70–1 Saatchi & Saatchi + Duke 71–2, 143 sales function 15, 21, 25–6, 36, 116–18, 146 Salesforce.com 157 Santi, Paolo 108 SAP 59, 186 Saunders, Charles 211 savings 115 Sawa Orchards 29–31 Scandinavian countries 6–7 see also Norway Schmidt, Eric 136 Schneider Electric 150 Schulman, Dan 161–2 Schumacher, E.F. 104–5, 105 Schweitzer, Louis 1, 2, 3, 4, 179 SCM (supply chain management) systems 59 SCOR (supply chain operations reference) model 67 Seattle 107 SEB 157 self-sufficiency 8 selling less 123–4 senior managers 122–4, 199 see also CEOs; organisational change sensors 65–6, 106, 118, 135, 201 services 9, 41–3, 67–8, 124, 149 frugal 60–3, 216 value-added 62–3, 76, 150, 206, 209 Shapeways 51, 132 shareholders 14, 15, 76, 123–4, 180, 204–5 sharing 9–10, 193 assets 159–61, 167 customers 156–8 ideas 63–4 intellectual assets 171–2 knowledge 153 peer-to-peer 136–9 resources 56–7, 159–61, 167 sharing economy 9–10, 17, 57, 77, 80, 84–7, 108, 124 peer-to-peer sharing 136–9 sharing between companies 159–60 shipping costs 55, 59 shopping experience 121–2 SIEH hotel group 172–3 Siemens 117–18, 150, 187–9, 215, 216 Sigismondi, Pier Luigi 100 Silicon Valley 42, 98, 109, 150, 151, 162, 175 silos, breaking out of 36–7 Simple Bank 124–5 simplicity 8, 41, 64–5, 170, 194 Singapore 175 Six Sigma 11 Skillshare 85 SkyPlus 62 Small is Beautiful (Schumacher, 1973) 104–5 “small is beautiful” values 8 small and medium-sized businesses see SMBs Smart + Connected Communities 29 SMART car 119–20 SMART strategy (Siemens) 188–9 smartphones 17, 100, 106, 118, 130, 131, 135, 198 in health care 110, 111 see also apps SmartScan 29 SMBs (small and medium-sized businesses) 173, 174, 175, 176 SMS-based systems 42–3 SnapShot 116 SNCF 41–3, 156–7, 167 SoapBox 28–9 social business model 206–7 social comparison 109 social development 14 social goals 94 social learning 113 social manufacturing 47, 50–1 social media 16, 71, 85, 106, 108, 168, 174 for marketing 61, 62, 143 mining 29, 58 social pressure of 119 tools 109, 141 and transaction costs 133 see also Facebook; social networks; Twitter social networks 29, 71, 72, 132–3, 145, 146 see also Facebook; Twitter social pressure 119 social problems 82, 101–2, 141, 142, 153, 161–2, 204 social responsibility 7, 10, 14, 141, 142, 197, 204 corporate 77, 82, 94, 161 social sector, working with 161–2 “social tinkerers” 134–5 socialising education 112–14 Sofitel 173 software 72 software as a service (SaaS) 60 solar power 136, 201 sourcing, local 51–2, 56 Southwest Airlines 60 Spain 5, 6, 103 Spark 48 speed dating 175, 176 spending, on R&D 15, 22, 23, 28, 141, 149, 152, 171, 187 spiral economy 77, 87–90 SRI International 49, 52 staff see employees Stampanato, Gary 55 standards 78, 196 Starbucks 7, 140 start-ups 16–17, 40–1, 61, 89, 110, 145, 148, 150, 169, 216 investing in 137–8, 157 as partners 42, 72, 153, 175, 191, 206 see also Nest Labs; Silicon Valley Statoil 160 Steelcase 142 Stem 151 Stepner, Diana 165 Stewart, Emma 196–7 Stewart, Osamuyimen 201–2 Sto Corp 84 Stora Enso 195 storytelling 112, 113 Strategy& see Booz & Company Subramanian, Prabhu 114 substitution of resources 92 subtractive manufacturing 48 Sun Tzu 158 suppliers 67–8, 83, 148, 153, 167, 176, 192–3 collaboration with 76, 155–6 sharing with 59–60, 91 visibility 59–60 supply chain management see SCM supply chain operations reference (SCOR) model 67 supply chains 34, 36, 54, 65, 107, 137, 192–3 carbon footprint 156 costs 58, 84 decentralisation 66–7 frugal 54–60 integrating 161 small-circuit 137 sustainability 137 visibility 34, 59–60 support 135, 152 sustainability xix, 9, 12, 72, 77–80, 82, 97, 186 certification 84 as competitive advantage 80 consumers and 95, 97, 101–4 core design principle 82–4, 93, 195–6 and growth 76, 80, 104–5 perceptions of 15–16, 80, 91 recommendations for managers 90–3 regulatory demand for 78–9, 216 standard bearers of 80, 97, 215 see also Accor; circular economy; Kingfisher; Marks & Spencer; Tarkett; Unilever sustainable design 82–4 see also C2C sustainable distribution 57, 161 sustainable growth 72, 76–7 sustainable lifestyles 107–8 Sustainable Living Plan (Unilever) 94–7, 179, 203–4 sustainable manufacturing 9, 52 T “T-shaped” employees 70–1 take-back programmes 9, 75, 77, 78 Tally 196–7 Tarkett 73–7, 80, 84 TaskRabbit 85 Tata Motors 16, 119 Taylor, Frederick 71 technical design 37–8 technical support, by customers 146 technology 2, 14–15, 21–2, 26, 27 TechShop 9, 70, 134–5, 152, 166–7 telecoms sector 53, 56 Telefónica 147 telematic monitoring 116 Ternois, Laurence 42 Tesco 102 Tesla Motors 92, 172 testing 28, 42, 141, 170, 192 Texas Industries 159 Textoris, Vincent 127 TGV Lab 42–3 thermostats 98–100 thinking, entrenched 14–16 Thompson, Gav 147 Timberland 90 time 4, 7, 11, 41, 72, 129, 170, 200 constraints 36, 42 see also development cycle tinkerers 17–18, 133–5, 144, 150, 152, 153, 165–7, 168 TiVo 62 Tohamy, Noha 59–60 top-down change 177–8 top-down management 69 Total 157 total quality management (TQM) 11 total volatile organic compounds see TVOC Toyota 44, 100 Toyota Sweden 106–7 TQM (total quality management) 11 traffic 108, 116, 201 training 76, 93, 152, 167, 170, 189 transaction costs 133 transparency 178, 185 transport 46, 57, 96, 156–7 Transport for London 195 TrashTrack 107 Travelocity 174 trial and error 173, 179 Trout, Bernhardt 45 trust 7, 37, 143 TVOC (total volatile organic compounds) 74, 77 Twitter 29, 62, 135, 143, 147 U Uber 136, 163 Ubuntu 202 Uchiyama, Shunichi 50 UCLA Health 202–3 Udacity 61, 112 UK 194 budget cuts 6 consumer empowerment 103 industrial symbiosis 160 savings 115 sharing 85, 138 “un-management” 63–4, 64 Unboundary 154 Unilever 11, 31, 57, 97, 100, 142, 203–5, 215 and sustainability 94–7, 104, 179, 203–4 University of Cambridge Engineering Design Centre (EDC) 194–5 Inclusive Design team 31 Institute for Sustainability Leadership (CISL) 158–9 upcycling 77, 88–9, 93, 159 upselling 189 Upton, Eben 135–6 US 8, 38, 44, 87, 115, 133, 188 access to financial services 13, 17, 161–2 ageing population 194 ageing workforce 13 commuting 131 consumer spending 5, 6, 103 crowdfunding 137–8, 138 economic pressures 5, 6 energy use 103, 119, 196 environmental awareness 7, 102 frugal innovation in 215–16, 218 health care 13, 110, 208–13, 213 intellectual property 171 onshoring 55 regulation 8, 78, 216 sharing 85, 138–9 shifting production from China to 55, 56 tinkering culture 18, 133–4 user communities 62, 89 user interfaces 98, 99 user-friendliness 194 Utopies 91 V validators 144 value 11, 132, 177, 186, 189–90 aspirational 88–9 to customers 6–7, 21, 77, 87, 131, 203 from employees 217 shareholder value 14 value chains 9, 80, 128–9, 143, 159–60, 190, 215 value engineering 192 “value gap” 54–5 value-added services 62–3, 76, 150, 206, 209 values 6–7, 14, 178, 205 Vandebroek, Sophie 169 Vasanthakumar, Vaithegi 182–3 Vats, Tanmaya 190, 192 vehicle fleets, sharing 57, 161 Verbaken, Joop 118 vertical integration 133, 154 virtual prototyping 65 virtuous cycle 212–13 visibility 34, 59–60 visible learning 112–13 visioning sessions 193–4 visualisation 106–8 Vitality 111 Volac 158–9 Volkswagen 4, 44, 45–6, 129, 144 Volvo 62 W wage costs 48 wages, in emerging markets 55 Waitrose, local suppliers 56 Walker, James 87 walking the walk 122–3 Waller, Sam 195 Walmart 9, 18, 56, 162, 216 Walton, Sam 9 Wan Jia 144 Washington DC 123 waste 24, 87–9, 107, 159–60, 175, 192, 196 beautifying 88–9, 93 e-waste 24, 79, 87–8, 121 of energy 119 post-consumer 9, 75, 77, 78, 83 reducing 47, 74, 85, 96, 180, 209 of resources 169–70 in US health-care system 209 see also C2C; recycling; reuse water 78, 83, 104, 106, 158, 175, 188, 206 water consumption 79, 82–3, 100, 196 reducing 74, 75, 79, 104, 122–3, 174, 183 wealth 105, 218 Wear It Share It (Wishi) 85 Weijmarshausen, Peter 51 well-being 104–5 Wham-O 56 Whirlpool 36 “wicked” problems 153 wireless technologies 65–6 Wiseman, Liz 164 Wishi (Wear It Share It) 85 Witty, Andrew 35, 35–6, 37, 39, 217 W.L.

Rethinking Capitalism: Economics and Policy for Sustainable and Inclusive Growth

by

Michael Jacobs

and

Mariana Mazzucato

Published 31 Jul 2016

At the same time as this retrofitting effort, another major job-creating and export-promoting route is the design of sustainable production equipment and infrastructure adequate to the specific climatic and other conditions of the developing world, where in the past standardised equipment and processes—with inadequate scale and characteristics—have been adopted. ‘Green growth’ also supposes the return—and heightened importance—of product durability, accompanied by maintenance as a key service. Planned obsolescence and disposability were strategies for demand expansion in the face of saturated markets. The growth of the global middle classes, and of the wealthy (who buy luxury products), can amply compensate for a drop in the sales of lower-quality, disposable products, while also countering what would otherwise be an uncontrollable rise in the cost of materials.

…

This could then lead to a very active rental sector for organising second-, third- and Nth-hand markets in each country and across the world, along with the growth of disassembly, remanufacturing, recycling, reusing and other materials-saving processes. Information for 3-D printing replacement parts and the provision of regular upgrades for the maintenance of products could become standard practice. This would create a business model in which repair and reuse would take the place of planned obsolescence. With the ‘internet of things’, chips can be put on each product to provide usage histories, enabling a thriving rental and maintenance industry to assign adequate prices. In the advanced world, such a business strategy would create great quantities of jobs for displaced assembly workers in maintenance, upgrading, warehousing, parts ‘printing’, distribution and installation, while design, redesign and many other creative industries and services would employ university graduates.

…

It is being copied in the emerging economies and aspired to in the developing ones; it is hankered after by the layers of impoverished unemployed in the advanced world and rightly made the main target of attack by the environmentalists. The ICT industries, whose strategies originally evolved in the boom of the 1990s, found oil at its lowest price and abundant, extremely low-cost labour available in Asia. Unthinkingly, they were led to adopt the planned obsolescence model generalised in the 1960s to overcome the limits posed by the saturation of markets. Thus the intangible nature of information technologies did not express itself in imaginative strategies encouraging minimal use of materials and maximum upgradeability. Fortunately, that is now beginning to happen, alongside innovation in the reduction of energy use.

Hit Makers: The Science of Popularity in an Age of Distraction

by

Derek Thompson

Published 7 Feb 2017

Executives like Alfred Sloan, the CEO of General Motors, recognized that, by changing a car’s style and color every year, consumers might be trained to crave new versions of the same product. This insight—to marry the science of manufacturing efficiency and the science of marketing—inspired the idea of “planned obsolescence.” That means purposefully making products that will be fashionable or functional for only a limited time in order to encourage repeat shopping trips. Across the economy, companies realized that they could engineer turnover and multiply sales by constantly changing the colors, shapes, and styles of their goods.

…

Cosmopolitan magazine wrote: Raymond Loewy website, www.raymondloewy.com/about.html#7. Artisans and designers of the nineteenth century: “Up from the Egg.” It was available only in black: “The Model T Ford,” Frontenac Motor Company, www.modelt.ca/background.html. inspired the idea of “planned obsolescence”: “GM’s Role in American Life,” All Things Considered, NPR, April 2, 2009, www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=102670076. Hekkert’s grand theory begins: Paul Hekkert, “Design Aesthetics: Principles of Pleasure in Design,” Psychology Science 48, no. 2 (2006): 157–72. “typicality, novelty and aesthetic preference”: Paul Hekkert, Dirk Snelders, and Piet C.

…

Hodges, 128–29 The Office (television series), 240 Ogle, Matt, 68–70 On Exactitude in Science (Borges), 1 OODA (Observation, Orientation, Decision, and Action), 278, 280 Page, Jimmy, 233 Pajitnov, Alexey, 58 Pandora, 37, 67–68, 130 “The Paradox of Publicity” (Kovacs and Sharkey), 143 Pareto, Vilfredo, 179–180 Pareto principle (80-20 rule), 179–180 Parker, Sean, 34 Peale, Charles Willson, 32, 32n Peretti, Jonah, 301 Phaedrus (Plato), 150 philosophers, 60 Philosophical Dictionary (Voltaire), 119–120 phonographs, 289 photo-sharing applications, 8–9 Picasso, Pablo, 57 Pietroluongo, Silvio, 81, 82 Pissarro, Camille, 22, 23, 24, 312n22 Planck, Max, 60, 71 planned obsolescence, 49, 81n Plato, 27, 146, 150 poetry, 27 politics and elections development of opinions about, 125 and ideological “burn-in,” 130 and ignorance of voters, 40–41 political parties, 38–40, 41 political rhetoric, 86–92, 283 and public relations, 37–38 Polo, Marco, 1, 14–15 pop culture, 57 Porter, Michael, 75 predictability, 116–17.

Reset

by

Ronald J. Deibert

Published 14 Aug 2020

Manufacturers of consumer electronics of all kinds take extraordinary steps to discourage users from getting too curious about what goes on “beneath the hood,” including placing “warranty void if removed” stickers on the underside, using proprietary screws and other components that require special tools, or applying glue and solder to bind components together, making it virtually impossible to open the device without causing irreparable damage.288 That smartphone you hold in your hand is what’s known in engineering as a “black box” — you can observe its inputs and outputs, but its inner workings are largely a mystery to all but a select few. Part of the reason has to do with planned obsolescence, a syndrome inherent to consumer culture. Our gadgets are built, by design, not to last. The sooner they stop working, the more likely you’ll want an upgrade to a more recent version. And when you do, you’ll need some accessories and peripherals too, or you won’t be able to enjoy all of the new features.

…

Raw sewage combined with acid wash from the e-waste dismantling processes flows directly into the Yamuna River, its shores clogged with the largest accumulation of discarded plastic water bottles I’ve ever seen in my life.381 Putting aside the squalor and demoralizing child labour, there are many things to be learned from the Seelampur recycling district. For far too long, we have lived in a culture of disposable wealth and planned obsolescence. We have become accustomed to a regular turnover of our consumer electronics, and we don’t give much thought to them once they no longer work. To be sure, some great strides have been made in recycling. Instead of simply discarding things, many of us now neatly separate our plastics, glass, paper products, and batteries and place them in blue bins.

…

Simultaneously, public education could encourage a more robust sense of personal data ownership, and a less frivolous attitude towards data consumption. Seen this way, efforts to “unplug” and “disconnect” can be linked to a deeper sentiment around conservation: aversion to over-consumption of both energy and data, and a strong distaste for planned obsolescence and other forms of waste. It is worth underscoring how efforts to tame unbridled surveillance capitalism and encourage civic virtue and self-restraint mutually reinforce each other in ways that also support environmental rescue. Environmentalism’s ideals — getting “back to nature,” conserving resources, slowing down, recognizing the value of difference, and replacing instant gratification and endless consumption with an acknowledgement of the impact of our current practices on future generations — are the sorts of qualities we will need to embrace to mitigate the harms around social media.466 Conceptualizing “transgenerational publics” in the way that environmentalists do can help us think differently about the shadow cast on future generations not only by our excessive consumption and waste, but also by the data mining to which we consent that affects other individuals down the road (such as when we relentlessly photograph and then share over social media images of children who have not yet reached the age of consent).

5 Day Weekend: Freedom to Make Your Life and Work Rich With Purpose

by

Nik Halik

and

Garrett B. Gunderson

Published 5 Mar 2018

Your Wealth Capture Account takes care of that. 3 Percent for Inflation: Inflation, which erodes the value of your money, generally averages about 3 percent (conservatively). 3 Percent for Technological Change: As technology improves, the costs generally fall, but we tend to buy it more frequently. 3 Percent for Propensity to Consume: What starts off as a luxury quickly becomes a necessity. For example, it wasn’t that long ago that no one had a cell phone. Now everyone does — even homeless people. Once people get used to a certain lifestyle, they rarely are willing to give it up. 3 Percent for Planned Obsolescence: Household goods and appliances break down and need to be replaced. By planning and saving for these predictable and unavoidable things, we’re able to build wealth even in spite of them. Account #2: Living Wealthy Account The purpose of this account is to save money for guilt-free spending on eating out, shopping, vacations, courtside tickets, or whatever luxury brings you value, helps you relax, or restores your energy.

…

In fact, $1 in 1913 is worth about $.03 today. After moving from the gold standard to our current fiat currency system, a $100,000 savings in 1971 only has the purchasing power of $16,667 today. In light of inflation, there are other considerations that erode your purchasing power: Planned obsolescence: Products needing to be constantly replaced Technological advances: Future purchases that don’t even exist today As a rule of thumb you should ensure that you generate a minimum return of 7 percent per year growth to combat inflation. Anyone achieving less than 7 percent is going backwards.

…

Plan patents patience, and real estate investments peace peace of mind fund Peale, Norman Vincent Penney, J.C. people-pleasing tendencies perfectionism, and productivity Pericles personal services, as entrepreneurial opportunity phone expenses, as tax deduction physical inspections, of real estate investments planned obsolescence podcasting, as entrepreneurial opportunity Poshmark Power of Attorney, and estate planning The Power of Full Engagement (Loehr and Schwartz) The Power of Habit (Duhigg) precious metals, as Momentum investment opportunity pre-IPO funds price, and lifestyle (consumptive) expenses and real estate investments private equity investments processes, adjusting documenting fine-tuning procrastination Proctor, Bob productive expenses productivity, and failure and perfectionism productivity rituals professionalism, and purpose progress, tracking property leases property taxes property values, and tax lien certificates protective expenses purpose, and adventure and distractions and freedom and generosity and goal setting and peace and perfectionism and simplicity ways to live on purpose The Pursuit of Happyness (film) put options Q Quillen, Robert R real estate investments, advantages of multi-family units and cash flow and cash flow filters down payment hurdles and economic cycles as entrepreneurial opportunity example purchases exit strategies for finding the right property fix-up costs and leverage and location managing wisely and peace of mind fund physical inspections profits in and property cycle purchasing your first property real-life success stories and return on investment six bonuses in and sweat equity tips for recession resistance, and Growth investments and storage units of tax lien certificates recessions, and economic cycles recharge rituals record keeping, and improved planning recurring revenue model relationship capital Remelski, Troy rental properties, and Active/Passive Scale See also real estate investments research, and real estate investments retail sales, and Active/Passive Scale as entrepreneurial opportunity retirement, deconstructing the cultural paradigm for and government social welfare programs retirement plans, and failure of conventional investments as source of loans and taxes vs. real estate investments Retton, Mary Lou return on investment, and Growth investments and real estate investments revenue subscriptions, as entrepreneurial opportunity Rice, Jerry Ripple risk, and diversification and entrepreneurship and Growth investments rituals RMS Titanic robotics Rockefeller Formula Rohn, Jim Roosevelt, Eleanor Roosevelt, Franklin D.

The Great Fragmentation: And Why the Future of All Business Is Small

by

Steve Sammartino

Published 25 Jun 2014

They left out the bit about keeping all the profits for themselves. This economic model worked well until we reached the point where we owned everything we needed. But now the deal has entered its final phases and the gig is up. The industrial revolution is putting itself out of business. I wonder if they had a planned-obsolescence in mind. Unlearning The methods used by corporations became so effective at generating more for less that they’re making their own era an obsolete business method. Companies that want to thrive during the technology era need to seriously revise their economic playbook. The efficiencies these corporations generated have made high-end technology disposable, or at the very least, low cost.

…

These were terms that companies would never use directly with their customers, but that form a large part of their conversations with agencies and in boardroom discussions. But the gig is up, and just in case you don’t know which terms you should banish from the boardroom, here they are with my own personal definitions in some real, human language: The planned obsolescence. We’re going to make this thing in a way that it breaks on purpose. We’re going to leave out features we’ve already made so that our customers have to buy it again and/or upgrade. The roadblock. We’re going to buy media on every single channel all at the same time when we launch this product.

…

Add to this that the ‘rivers of gold’ that flowed from classified ads are also being taken over online by single-minded competitors, and we’ve witnessed a classic ‘David’ victory. Who do you trust? Do you trust a large media organisation that survives by running advertisements for giant global brands (who may well be polluting the earth and encouraging kids to eat food that makes them sick, or who make products with planned obsolescence) to tell you the truth about the world around you? Or do you trust a passionate ‘amateur’ writing a blog about a topic of interest and passion late on a Saturday night to share some valuable information with others for no money, no payoff and no vested interest other than sharing value with other people?

The Mesh: Why the Future of Business Is Sharing

by

Lisa Gansky

Published 14 Oct 2010

Design that reduces natural resource destruction and waste, which is ever more expensive, improves efficiency and reduces overall costs. heirloom design. or the half-life of crap. For years now, the common folklore in the West has been that the cheapest way to replace many appliances is to throw the old one away and buy a new one. “Planned obsolescence”—products designed with the expectation that they will have a short life and be replaced—has ruled the day. In contrast, the Mesh motivates designers to create timeless products that can be used over and over again. Saul Griffith, a respected physicist and inventor and a friend, has coined a name for this built-to-last practice: “heirloom design.”

…

See Loans/social lending Permission marketing Personalized products Mesh companies and product design Pet sharing, Mesh companies Phone service, Mesh companies Photo sharing, Mesh companies Population growth and growth of the Mesh in urban areas Porter, Michael Prius Privacy practices privacy-sensitive products and trust building Product design customer input, use of disposable versus heirloom modular personalization planned obsolescence shared goods, durability of standardization sustainable sustainable design waste, reusing Proprietary control, versus openness Prosper case study loan amounts dispersed by as niche business Public relations, lost trust, rebuilding Real estate Mesh companies See also Home exchange; Work-space sharing RecycleBank Recycle Now Recycling and reuse services and Geek Squad Mesh companies upcycling Walmart Share Club scenario RedesignMe REI Reinhart, James RelayRides Rent the Runway Repair services and big-box companies Mesh company possibilities Reputation.

The Great Race: The Global Quest for the Car of the Future

by

Levi Tillemann

Published 20 Jan 2015

Ford’s great rival, General Motors (GM), also practiced mass production. However, GM did not do so with the same single-minded zeal as Ford. GM was originally the amalgamation of many smaller automotive nameplates, which led it toward diversified mass production, product differentiation, and eventually planned obsolescence. This strategy was dubbed “Sloanism” after the company’s managerial genius, Alfred P. Sloan Jr.7 Like oil, autos became militarily important. In World War I, new weapons like the “cistern” (eventually known as the tank), motorized troop transports, and other weaponized vehicles proved decisive to victory.8 Three decades later, during World War II, America was clearly dominating the race for motorized wheels.

…

With car sharing it is also easier to justify the cost of higher-quality vehicles. This includes systems that could make cars safer, more comfortable, more efficient and give them better performance. For instance, today cars are designed to last a couple of hundred thousand miles. The business model underlying this planned obsolescence means that there’s no good reason to invest in materials that would increase that life span. At a recent press conference the head of Nissan R&D explained that the company would not use carbon fiber because it was “too durable.”7 And in the context of individual vehicle ownership, it is hard to justify the cost or durability of carbon fiber.

…

See also Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant (Japan) Nuclear Reform Special Task Force, Japanese, 248 Nuclear Regulatory Agency, Japan, 247 Obama (Barack) administration, 153, 167–69, 170, 171, 172, 174, 177, 181–83, 239, 252 Ohga, Kiho, 140, 194, 195 Ohno, Taiichi, 54 oil Bush administration and, 110, 111 and California’s prelude to the Great Race, 33, 38 and CARB timeline, 73 and cars in the future, 256, 257–58 Chinese demand for, 101, 115, 217–18, 252 and “death” of EV, 92 and debate about EVs, 238 and financial crisis of 2008, 163 government role in supplying, 7 and history of the global auto industry, 22, 24–25 and incentivizing demand for EVs, 11 independence from, 258 Japanese demand for, 49, 59–60, 122, 123, 126, 238 and methanol-powered cars, 72 and regulation of fuel economy, 142 Schwarzenegger’s concerns about, 143 U.S. demand for, 11, 90, 103, 109, 110, 111, 141, 183 and winning the Great Race, 254 Okuda, Hiroshi, 83 Olympics (Beijing, 2008), 203–7, 217, 225, 227, 250, 253 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 66–67 Otto Cycle, 83 Ouyang Mingao, 204, 222–23, 224, 250, 251 Ovshinsky, Iris, 25 Ovshinsky, Stanford, 24–25 ownership, car, 255, 263–65, 272 Pacific Gas and Electric, 202 Panasonic, 197–98, 215, 243 Panda Motor Corporation, 96–97 parking: of automated vehicles, 270 Partnership for a New Generation of Vehicles (PNGV), 26, 81, 82, 109, 111, 169, 170 Paulson, Henry “Hank,” 158, 161, 166 Pavley, Fran, 141–42 Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation, 167 Peres, Shimon, 221 Persian Gulf War (1990-91): Humvee in, 29 Peugeot, 201 Phillips, Clay, 74 piston-in-cylinder architecture, 61, 62–64 pizza delivery: by automated vehicle, 266–67, 272 planned obsolescence, 22 platooning, 271 Platt Brothers, 45 “point-line system,” 251 policy and future of auto industry, 6, 7, 256, 273–74 and technology in the future, 273–74 and winning the Great Race, 253, 254 See also industrial policy; specific nation or policy politics battery standards and, 262 and California’s regulations, 32, 144–45 in China, 209, 213, 214, 249–50, 253 and debate about EVs, 238–39 environmental issues and, 32, 75 and future of auto industry, 6 and future of U.S., 254 global auto industry and, 261 and Japanese auto industry, 49, 134 and Japanese-U.S. relations, 44 U.S. auto industry and, 153, 161, 173–76, 274 and winning the Great Race, 27, 254 pollution.

The Smart Wife: Why Siri, Alexa, and Other Smart Home Devices Need a Feminist Reboot

by

Yolande Strengers

and

Jenny Kennedy

Published 14 Apr 2020

Through their disturbing exposé, Crawford and Joler show how each simple and convenient interaction with Alexa “requires a vast planetary network, fueled by the extraction of nonrenewable materials, labor, and data.” They reveal the circuitry of largely hidden impacts—from the mining of lithium batteries to planned obsolescence resulting in e-waste—that span every corner of the globe, extending far beyond the direct consumption of resources inside the home. What is concerning here is how smart wives like Alexa are deliberately designed to shield consumers from understanding and acknowledging their planetary impacts.

…

We also have a rich history to draw from that illustrates that the collapse of societies, economies, and entire civilizations can and does happen.121 On a more optimistic note, ecofeminist ideology is already being realized through the continual existence and reassertion of subsistence economies and grassroots movements as well as emerging global networks such as Wild Law, which gives nature its own legal rights.122 Other movements are holding electronics companies accountable for their troubling planetary impacts. The European Union and United States, for example, are establishing “right to repair” laws that are intended to make devices last longer and be easier to mend.123 These laws are an attempt to curtail “planned obsolescence” (whereby companies design devices to fail or stop supporting their repair in order to encourage consumers to upgrade).124 There is cause to hope, then, that these new Borg kings will have a limited reign or undergo radical transformation. Within this planetary doom and gloom, it is difficult to see what purpose the smart wife serves.

…

Catie Keck, “Right to Repair Is Less Complicated and More Important Than You Might Think,” Gizmodo, May 10, 2019, https://gizmodo.com/right-to-repair-is-less-complicated-and-more-important-1834672055?IR=T; Roger Harrabin, “EU Brings in ‘Right to Repair’ Rules for Appliances,” BBC News, October 1, 2019, https://www.bbc.com/news/business-49884827. 124. Sabine LeBel, “Fast Machines, Slow Violence: ICTs, Planned Obsolescence, and E-waste,” Globalizations 13, no. 3 (2016): 300–309. 125. Maria Mies and Shiva sum up this hypocrisy in their book Ecofeminism: “To ‘catch-up’ with the men in their society, as many women still see as the main goal of the feminist movement, particularly those who promote a policy of equalization, implies a demand for a greater, or equal share of what, in the existing paradigm, men take from nature.

Peak Everything: Waking Up to the Century of Declines

by

Richard Heinberg

and

James Howard (frw) Kunstler

Published 1 Sep 2007

In a world where a genuine sense of mastery is elusive, and feelings of impotency abound, the well-designed product can provide a symbolism of autonomous proficiency and power.3 As industrial design progressed after World War II and into the ’50s, ’60s, ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s, style continued to evolve, as it had to in order to serve the purposes of fashion and planned obsolescence. Images and objects became more frankly seductive and more directly suggestive of the very qualities of which the lives of human beings were in fact being systematically drained — autonomy and creativity. In hindsight, it appears that Deco was the last hiccup of design originality for the hydrocarbon age.

…