popular electronics

description: an American magazine that was published from 1954 to 1985, covering electronic projects, kits, and new products

58 results

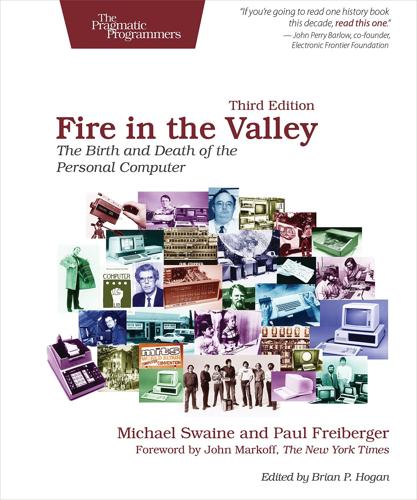

Fire in the Valley: The Birth and Death of the Personal Computer

by

Michael Swaine

and

Paul Freiberger

Published 19 Oct 2014

The Altair had the potential, at least in miniature, of doing everything a large mainframe computer could do. Solomon was convinced of it and told Roberts as much. But he didn’t voice his concern that the message might not get across to the Popular Electronics readers. Art Salsberg told him that Popular Electronics had to offer its readers more than just instructions for building the device. To prove that the Altair was a serious computer, Popular Electronics had to also offer one solid application, a practical purpose for the Altair that could be demonstrated right away. What that application might be, Solomon had no idea. Delivering the Goods The deadline arrived for Roberts to deliver the prototype computer to Solomon.

…

–Chuck Peddle, computer designer Bill Gates, Paul Allen, and other computer enthusiasts relied on the hobbyist electronics magazines like Popular Electronics and Radio-Electronics to keep up with the latest technological developments. In the early 1970s, what Gates and Allen were seeing in the pages of those magazines served to frustrate them as much as excite them. Most of the magazines’ readers knew something about computers, and many knew a lot more than that—and every one of them now wanted to own a computer. The computer aficionados who read Popular Electronics and Radio-Electronics were an opinionated lot; they knew precisely what they did and didn’t want in a computer.

…

Lancaster’s TV Typewriter, for all its visionary appeal, was nevertheless only a terminal: an I/O (input/output) device that would link to a mainframe computer. It didn’t constitute the personal computer that the electronics hobbyists desperately wanted. * * * Figure 16. Art Salsberg and Les Solomon Salsberg, editorial director of Popular Electronics (left), and Les Solomon, its technical editor, pose with the historic January 1975 Altair cover. (Courtesy of Paul Freiberger) At the time Lancaster’s article was published, Popular Electronics technical editor Leslie (Les) Solomon was actively seeking a computer story for his magazine. Solomon and editorial director Arthur Salsberg wanted to publish a piece on building a computer at home.

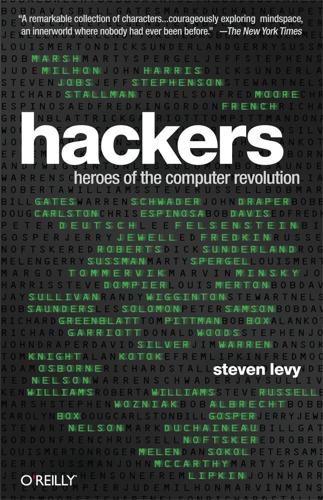

Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution - 25th Anniversary Edition

by

Steven Levy

Published 18 May 2010

After a quick day-trip to New Hampshire to meet the folks at the new hobbyist magazine Byte, Lee was able to get to a workbench and find the problem—a small wire had come loose. They went back to the offices of Popular Electronics and turned it on. “It looked like a house on fire,” Solomon later said. He had immediately grasped that he was looking at a complete computer. The resulting Popular Electronics article spoke of an intelligent computer terminal. But it was clearly a computer, a computer that, when Processor Technology packaged it in its pretty blue case with walnut sides, looked more like a fancy typewriter without a platen.

…

Long-haired prankster who reveled in revealing technological secrets at Homebrew Club. Helped “liberate” Altair BASIC program on paper tape. Sol Computer. Lee Felsenstein’s terminal-and-computer, built in two frantic months, almost the computer that turned things around. Almost wasn’t enough. Les Solomon. Editor of Popular Electronics, the puller of strings who set the computer revolution into motion. Marty Spergel. The Junk Man, the Homebrew member who supplied circuits and cables and could make you a deal for anything. Richard Stallman. The Last of the Hackers, he vowed to defend the principles of hackerism to the bitter end.

…

It would revive Community Memory, it would galvanize the world, it would be the prime topic of conversation at Mike Quinn’s and PCC potlucks, and it would even lay a foundation for the people’s entry into computers—which would ultimately topple the evil IBM regime, thriving on Cybercrud and monopolistic manipulation of the marketplace. But even as Lee’s nose was reddening from the reflection of the sun on the schematics of his remarkable terminal, the January 1975 issue of Popular Electronics was on its way to almost half a million hobbyist-subscribers. It carried on its cover a picture of a machine that would have as big an impact on these people as Lee imagined the Tom Swift Terminal would. The machine was a computer. And its price was $397. • • • • • • • • It was the brainchild of a strange Floridian running a company in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

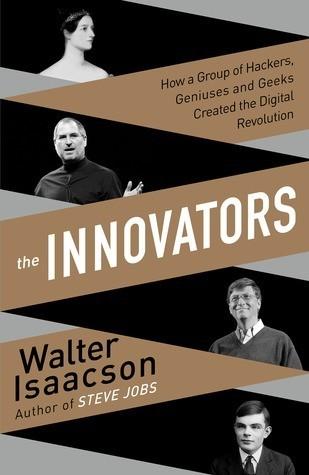

The Innovators: How a Group of Inventors, Hackers, Geniuses and Geeks Created the Digital Revolution

by

Walter Isaacson

Published 6 Oct 2014

(The venerable shipping service went out of business a few months later.) So the January 1975 issue of Popular Electronics featured a fake version. As they were rushing the article into print, Roberts still hadn’t picked a name for it. According to Solomon, his daughter, a Star Trek junkie, suggested it be named after the star that the spaceship Enterprise was visiting that night, Altair. And so the first real, working personal computer for home consumers was named the Altair 8800.113 “The era of the computer in every home—a favorite topic among science-fiction writers—has arrived!” the lede of the Popular Electronics story exclaimed.114 For the first time, a workable and affordable computer was being marketed to the general public.

…

Following in the footsteps of Jack Kilby of Texas Instruments, Roberts next forayed into the electronic calculator business. Understanding the hobbyist mentality, he sold his calculators as unassembled do-it-yourself kits, even though assembled devices would not have cost much more. By then he’d had the good fortune of meeting Les Solomon, the technical editor of Popular Electronics, who had visited Albuquerque on a story-scouting tour. Solomon commissioned Roberts to write a piece, whose headline, “Electronic Desk Calculator You Can Build,” appeared on the November 1971 cover. By 1973 MITS had 110 employees and $1 million in sales. But pocket calculator prices were collapsing, and there was no profit left to be made.

…

A computer created in, say, a basement in Iowa that no one writes about becomes, for history, like a tree falling in Bishop Berkeley’s uninhabited forest; it’s not obvious that it makes a sound. The Mother of All Demos helped Engelbart’s innovations catch on. That is why product launches are so important. The MITS machine might have languished with the unsold calculators in Albuquerque, if Roberts had not previously befriended Les Solomon of Popular Electronics, which was to the Heathkit set what Rolling Stone was for rock fans. Solomon, a Brooklyn-born adventurer who as a young man had fought alongside Menachem Begin and the Zionists in Palestine, was eager to find a personal computer to feature on the cover of his magazine. A competitor had done a cover on a computer kit called the Mark-8, which was a barely workable box using the anemic Intel 8008.

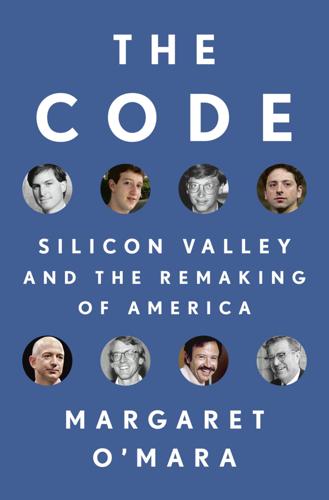

The Code: Silicon Valley and the Remaking of America

by

Margaret O'Mara

Published 8 Jul 2019

Many started by selling Altairs and peripherals, but often moved into the business of building whole new microcomputers altogether.2 With the blessing of Popular Electronics editor Les Solomon, who promised a cover story, Felsenstein joined with the Proc Tech team to commercialize the Tom Swift Terminal. Despite the pains they took not to tread on Altair’s toes—the unit was designed as an “intelligent terminal” rather than a computer—the effort ultimately produced an important Altair competitor, the Sol. In another first, the Sol included BASIC software as well as hardware. The user base had grown beyond people who could simply consult Dr. Dobb’s to program their machine. As an indication of how large Popular Electronics still loomed on the early personal-computer scene, they named it in honor of Les Solomon.3 Across America, start-ups bubbled up nearly anyplace where there were lots of engineers and active hobbyist chatter.

…

Socially awkward and finding real-life interpersonal connection difficult (later in life, he received a diagnosis of mild autism), Felsenstein decided to devote his life to creating technology that helped people powerfully and efficiently share information—but that was so simple anyone could use it.1 Born in 1945 in Philadelphia, Lee Felsenstein was less than a decade younger than captains of the semiconductor industry like Andy Grove and Jerry Sanders. Yet his generation’s experience was so different that it might as well have been a century. Like so many boys of his postwar generation, he’d plop down a carefully saved quarter each month to buy the latest edition of Popular Electronics, poring over the glorious multipage spreads within that described how to make your own electronic gadgets. At age eleven, he built a crystal radio out of a kit discarded by his older brother. When he was twelve, Sputnik rocketed into space, and he built a small satellite that won third place in the regional science fair.

…

He spent the next few years bouncing back and forth across the Bay between Berkeley and the newly christened Silicon Valley, continuing to pursue his dream of building technical tools that would allow people to escape the establishment’s clutches, and possibly overthrow the system altogether.6 * * * — At the same time Lee Felsenstein was poring through Popular Electronics and taking apart radio sets, Liz Straus was sitting in a classroom in Dana Hall, an all-girls’ prep school in Wellesley, Massachusetts. Math and science were already in her blood: Straus’s mother was a science teacher at the school, and her engineer father was deeply involved in computer and radar research at MIT.

Exploding the Phone: The Untold Story of the Teenagers and Outlaws Who Hacked Ma Bell

by

Phil Lapsley

Published 5 Feb 2013

But the contagion was threatening to spread more widely via ads, like one that appeared in 1963. Slash Communication Costs with TELA-TONE You’ve been reading about it. Now you can build it yourself. No license required to operate. 5,000 mile range. Complete details, $5 or money back. Tela-tone, Box 4304, Pasadena, Calif. Or the following gem from the January 1964 hobbyist magazine Popular Electronics: TOLL Free Distance Dialing. By-passes operators and billing equipment. Build for $15.00. Ideal for Telephone Company Executives. Plans $4.75. Seaway Electronics, 6311 Yucca St., Hollywood 28, California. “Ideal for Telephone Company Executives.” Whoever got mail at 6311 Yucca Street in Hollywood seemed to have a sense of humor.

…

It was a computer on a chip that executed a few hundred thousand instructions per second. Engineers called it the “first truly useable microprocessor.” Intel didn’t know it yet but that chip would be the thing that started the home computer revolution and would lead to Intel’s eventual domination of the microprocessor market. In January 1975 Popular Electronics, a geeky electronic hobbyist magazine, offered its readers an unbelievable chance to own their own slice of high-tech heaven. “Project Breakthrough!” the cover fairly shouted. “World’s First Minicomputer Kit to Rival Commercial Models . . . ‘Altair 8800.’” The cover’s photo showed a large metal box—blue, as it happened—about the size of three toasters, its nerd-sexy front panel festooned with dozens of tiny toggle switches and red LEDs.

…

It came as a kit, consisting of empty circuit boards and bags full of electronic components you had to solder together. The price? A mere $397, mail-ordered from a company no one had ever heard of: MITS in Albuquerque, New Mexico. MITS’s phone began ringing off the hook. Within weeks thousands of orders were called in for the Altair 8800, more than four hundred in a single day. The Popular Electronics editor Les Solomon said later, “The only word which could come into mind was ‘magic.’ You buy the Altair, you have to build it, then you have to build other things to plug into it to make it work. You are a weird-type person. Because only weird-type people sit in kitchens and basements and places all hours of the night, soldering things to boards to make machines go flickety-flock.”

The Chip: How Two Americans Invented the Microchip and Launched a Revolution

by

T. R. Reid

Published 18 Dec 2007

Among the countless new applications that people dreamed up for the computer-on-a-chip was, of all things, a computer—a completely new computer designed, not for big corporations or mighty bureaucracies, but rather for ordinary people. The personal computer got its start in the January 1975 issue of Popular Electronics magazine, a journal widely read among ham radio buffs and electronics hobbyists. The cover of that issue trumpeted a “Project Breakthrough! World’s First Minicomputer Kit to Rival Commercial Models.” Inside, the reader found plans for a homemade “microcomputer” in which the Intel 8080 microprocessor replaced hundreds of individual logic chips found in the standard office computer of the day. The Popular Electronics kit was strictly bare-bones, but it gave anybody who was handy with a soldering iron the chance to have a computer—for a total investment of about $800.

…

It was a community that lived by the old Leninist maxim, “From each according to his ability, to each according to his need.” If you needed a program that would make your homebrew computer compute square roots, and if I had the ability to write a program to do just that, I would proudly share my handiwork with you—for free. But among the first to start programming the Popular Electronics 8080-based computer was a Harvard undergraduate who had a different idea. In the late 1970s he wrote the first genuinely useful program for 8080-based PCs, a simple version of the BASIC programming language. And then he did an amazing thing: he charged money for it. For this, the young programmer was attacked and vilified by many of his fellow buffs.

…

“computer on a chip”: Cf. advertisement in Electronics News, Nov. 15, 1971. the first patent awarded for a microprocessor: U.S. Patent No. 3,757,306. actually was a computer on a chip: U.S. Patent No. 4,074,351. The introductory price was $200: Libes, p. 68. “Project Breakthrough! . . .”: Popular Electronics, January 1975. Homebrew Computer Club: Time, Jan. 3, 1983. “Clearly, a world with . . .”: Interview with Noyce. Chapter 9: DIM-I a summer day in 1976: The New York Times, July 11, 1976, sec. 3, p. 13; interview with Dr. Uta Merzbach of the Smithsonian Institution. had watched sales fall: The New York Times, Jan. 3, 1982, sec. 4, p. 9.

Gambling Man

by

Lionel Barber

Published 3 Oct 2024

Sometime in the fall of 1976, Masa claims to have experienced an epiphany, a life-changing experience which irrevocably shaped his future business career.13 He picked up a copy of Popular Electronics in his local Safeway supermarket and spotted an image of the new Intel 8080 microprocessor. He imagined he was watching a film scene or listening to a moving piece of music. ‘It was exactly that same feeling. I was tingling all over and warm tears were rolling down my face.’ Masa’s account – repeated endlessly in interviews and biographies – is almost identical to Bill Gates’s story of being shown a copy of Popular Electronics magazine in January 1975. Gates, then a second-year student at Harvard, was so blown away reading about the Altair 8800 microprocessor that he dropped out and co-founded his own company – Microsoft – in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

…

Gates, then a second-year student at Harvard, was so blown away reading about the Altair 8800 microprocessor that he dropped out and co-founded his own company – Microsoft – in Albuquerque, New Mexico. ‘I was genuinely moved,’ Gates recalled. ‘In my opinion, Popular Electronics completely changed the relationship between humans and computers.’14 Whether Masa’s story is true or a copycat experience is less important, perhaps, than the fact that the young Japanese student was following Den Fujita’s advice and fast developing an interest in technology. It would have been strange if he hadn’t. Holy Names in Oakland was only an hour’s drive from the Mecca of entrepreneurship and innovation, the area around San Jose in Santa Clara County known as Silicon Valley.

…

In the world of computer magazine publishing, there was really one name that mattered: Ziff-Davis, based in New York. Run by William Ziff, the family patriarch, the company had been a leader in consumer publishing since the 1920s. After the Second World War, Ziff launched car and photography magazines, later diversifying into computer publishing. Ziff’s titles like Popular Electronics – the magazine that had made such an impact on Masa and Bill Gates at the start of their careers – produced reviews which could make or break the launch of new products. After a ten-minute meeting with Masa at Ziff’s headquarters on Fifth Avenue in New York, Ziff agreed to allow SoftBank to publish Japanese-language versions of PC Week.

The Road Ahead

by

Bill Gates

,

Nathan Myhrvold

and

Peter Rinearson

Published 15 Nov 1995

I was planning to fly home to Seattle for the holidays, and Paul was staying in Boston. On an achingly cold Massachusetts morning a few days before I left, Paul and I were hanging out at the Harvard Square newsstand, and Paul picked up the January issue of Popular Electronics. This is the moment I described at the beginning of the Foreword. This gave reality to our dreams about the future. January 1975 issue of Popular Electronics On the magazine's cover was a photograph of a very small computer, not much larger than a toaster oven. It had a name only slightly more dignified than Traf-O-Data: the Altair 8800 ("Altair" was a destination in a Star Trek episode).

…

My special gratitude to my collaborators, Peter Rinearson and Nathan Myhrvold. FOREWORD The past twenty years have been an incredible adventure for me. It started on a day when, as a college sophomore, I stood in Harvard Square with my friend Paul Allen and pored over the description of a kit computer in Popular Electronics magazine. As we read excitedly about the first truly personal computer, Paul and I didn't know exactly how it would be used, but we were sure it would change us and the world of computing. We were right. The personal-computer revolution happened and it has affected millions of lives. It has led us to places we had barely imagined.

…

We're still late with projects sometimes but a lot less often than we would have been if we hadn't had those scary baby-sitters. Microsoft started out in Albuquerque, New Mexico, in 1975 because that's where MITS was located. MITS was the tiny company whose Altair 8800 personal-computer kit had been on the cover of Popular Electronics. We worked with it because it had been the first company to sell an inexpensive personal computer to the general public. By 1977, Apple, Commodore, and Radio Shack had also entered the business. We provided BASIC for most of the early personal computers. This was the crucial software ingredient at that time, because users wrote their own applications in BASIC rather than buying packaged applications.

Computer: A History of the Information Machine

by

Martin Campbell-Kelly

and

Nathan Ensmenger

Published 29 Jul 2013

The typical hobbyist had cut his teeth in his early teens on electronics construction kits, bought through mail-order advertisements in one of the popular electronics magazines. Many of the hobbyists were active radio amateurs. But even those who were not radio amateurs owed much to the “ham” culture, which descended in an unbroken line from the early days of radio. After World War II, radio amateurs and electronics hobbyists moved on to building television sets and hi-fi kits advertised in magazines such as Popular Electronics and Radio Electronics. In the 1970s, the hobbyists lighted on the computer as the next electronics bandwagon.

…

What brought together these two groups, with such different perspectives, was the arrival of the first hobby computer, the Altair 8800. THE ALTAIR 8800 In January 1975 the first microprocessor-based computer, the Altair 8800, was announced on the front cover of Popular Electronics. The Altair 8800 is often described as the first personal computer. This was true only in the sense that its price was so low that it could be realistically bought by an individual. In every other sense the Altair 8800 was a traditional minicomputer. Indeed, the blurb on the front cover of Popular Electronics described it as exactly that: “Exclusive! Altair 8800. The most powerful minicomputer project ever presented—can be built for under $400.”

…

Page 232“fad” that “seemed to come from nowhere”: Douglas 1987, p. 303. Page 234“New Communalists”: Turner 2006, p. 4. Page 234“transform the individual into a capable, creative person”: Turner 2006, p. 84. Page 234“was one of the bibles”: Jobs 2005, p. 1. Page 235“Exclusive! Altair 8800”: Popular Electronics, January 1975, p. 33; reproduced in Langlois 1992, p. 10. Page 240“nit-picking technical debates”: Moritz 1984, p. 136. Page 241three leading manufacturers: See Langlois 1992 for an excellent economic analysis of the personal-computer industry. Page 242“The home computer that’s ready to work, play and grow with you . . . ”: Quoted in Moritz 1984, p. 224.

The Battery: How Portable Power Sparked a Technological Revolution

by

Henry Schlesinger

Published 16 Mar 2010

It’s worth noting that a variation of the Gernsback story was reprised in 1975 when a small Albuquerque, New Mexico, company, Micro Instrumentation and Telemetry Systems (MITS) introduced the Altair 8800 for $395 (about $1,500 in constant dollars) through the mail. Considered the first “microcomputer,” the unit appeared on the cover of Popular Electronics in January 1975. The Altair (named after the brightest star in the Aquila constellation) offered no keyboard, monitor, or tape reader, and boasted a whopping 256 bytes of memory. Enthusiasts programmed it in binary machine language with toggle switches and little lights on the front panel. Thousands of the units were sold, and a Harvard student, William Henry Gates III (“Bill” to his friends), contacted the company with an offer to write code for the machine.

…

And even then, it wasn’t the lead item, following an announcement that Eve Arden would be starring in a new show called Our Miss Brooks, “…playing the role of a school teacher who encounters a variety of adventures.” Eve Arden had somehow upstaged one of the most important technological breakthroughs of the twentieth century. Transistors fared only somewhat better in the now-defunct Herald Tribune and mainstream science and technology magazines like Popular Science and Popular Electronics. To be fair, the New York Times wasn’t alone in its seeming indifference. Aside from the professional technical journals and a few hobbyist publications, which hailed the announcement with varying degrees of geeky enthusiasm, the overall response was one of muted, earnest, and perfunctory reporting.

…

B., 78, 97–112, 150, 200, 281 telegraph, 103–109, 109, 110–12, 120, 130, 206, 248–49 Morse code, 97, 106–107, 112, 191, 195, 196, 206, 209 motor, electric, 21, 75, 85–96, 151, 170, 171–72 Davenport, 92–94 Faraday, 75, 75, 76–77, 92 Henry, 85–88, 92 Motorola, 230–31, 251 music, 218, 256, 257 Musschenbroek, Pieter van, 10, 24–27 myth, 4–9, 10, 259 name, battery, 142 Napoleon Bonaparte, 48, 58, 59–60, 65, 72, 99, 129 NASA, 264, 272, 276, 281 National Carbon Company, 179, 182, 183, 220, 228, 241 Nativist movement, 102–103 natural philosophy, 37–38, 60, 69 Nazism, 226, 234, 260 nerve impulses, electrical basis of, 40–41, 45 Netherlands, 82 newspaper trade, and telegraph, 132 Newton, Isaac, 14–15, 17, 18, 36, 39, 72, 75, 78 New York City, 29, 102, 111, 132, 134–39, 153–55, 182 Radio Row, 244 New York Sun, 148 New York Times, 141, 154, 196, 241, 246, 254 Nicholson, William, 44–45, 47, 63 nickel cadmium (NiCd) battery, 270, 271 nickel hydrogen rechargeable battery, 276, 276 nickel-metal hydride (NiMH) battery, 270, 271 Nike Ajax, 248 9-volt battery, 259 nitric acid battery, 67, 87, 95, 96, 110, 113, 139, 146 No. 6 battery, 213, 214, 215 Nokia, 278 Nollet, Jean-Antoine, 27–29, 33–34, 42 Norman, Robert, Newe Attractive, 11 observation, 2–4, 5 O’Neill, Eugene, Long Day’s Journey into Night, 156 optical telegraph systems, 98–99, 100, 103, 112, 123 Ørsted, Hans Christian, 73–74, 84 pad shovers, 135, 136, 138 Page, Charles, 95 Panic of 1837, 106 parallel circuit, 81 Paris, 132, 147, 148 patents, 49–50, 57, 88, 152, 187, 188, 207 battery, 49–50, 179 electric light, 147, 151 flashlight, 183 integrated circuit, 264 “7777 Patent,” 188 telegraph, 104, 105 telephone, 151, 157–60 transistor, 247 walkie-talkie, 232 wireless telegraph, 191 pee battery, 282 Pegasus, 5, 5 pen, electric, 170, 170, 171 Penfield Iron Works, 84, 91 Peregrinus, Petrus, 8–9, 12 Letter of, 9 Perikon-Perfect Pickard Contact, 207 Peripatetics, 14 Philadelphia, 29 Philco, 220 phonograph, 171, 172, 173, 175 amplifiers, 243–44 physics, 19, 43 Pickard, Greenleaf Whittier, 207 Pixie radio, 251 Pixii, Hyppolyte, 76 plague, 11–12 Planté, Gaston, 144–46 Planté cell, 144–46, 250 platinum, 67, 87, 96, 113, 147 Plato, 2 Pliny the Elder, 4–5, 12 Historia Naturalis, 4 pocket radio, 240 Regency, 251–57, 257, 258–61 Poe, Edgar Allan, “Some Words with a Mummy,” 63 Poggendorff, Johann Christian, 124–25 point-contact detectors, 207 polarization, 141, 144–45, 172, 173 Polish Detector, 233 pony express, 115 Pope, Alexander, 16–17 Pope, Frank L., Modern Practice of the Electric Telegraph, 140 Popov, Alexander, 187 popular culture, 242 transistor radio and, 256–58 Popular Electronics, 202, 246 Popular Mechanics, 211, 212 Popular Science, 212, 246 portability, 211, 215–16, 269, 275 LCDs, 266–69 radio, 216, 230, 230, 231–36, 240, 247, 251–61 rechargeable batteries, 268–73 twenty-first century, 274–78 power grid, 169, 224 primary battery, 144, 174 Princeton University, 88, 136 printing press, 10 Project Tinkertoy, 263 proximity fuse, 227–29, 229, 230, 238, 253 Ptolemy, 12 Pulsar digital watch, 268–69 Pulvermacher, J.

Gods and Robots: Myths, Machines, and Ancient Dreams of Technology

by

Adrienne Mayor

Published 27 Nov 2018

Even among people today who understand that an electrical circuit requires two wires, a mental picture persists of an empowering “juice” flowing through a single cable. Our “prescientific” intuitive vision coexists with modern scientific knowledge.43 In 1958, the author of a brief history of robots in Popular Electronics remarked on Talos’s “single ‘vein’ running from his neck to his ankle, stoppered somewhere in his foot by a large bronze pin.” Viewed in “modern terms,” the author mused, this conduit “could have been his main power cable and the pin his fuse.” Writing at the height of the Cold War, the author went on to declare that Talos was an ancient “Weapons Alert System and Guided Missile in one package!”

…

Wired, June, 72–79. Tassinari, Gabriella. 1992. “La raffigurazione de Prometeo creatore nella glittica romana.” Xenia Antiqua 1:61–116. ———. 1996. “Un bassorilievo del Thorvaldsen: Minerva e Prometeo.” Analecta Romana Instituti Danici 23:147–76. Tenn, William. 1958. “There Are Robots among Us.” Popular Electronics, December, 45–46. Truitt, E. R. 2015a. Medieval Robots: Mechanism, Magic, Nature, and Art. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ———. 2015b. “Mysticism and Machines.” History Today 65, 7 (July). Tyagi, Arjun. 2018. “Augmented Soldier: Ethical, Social and Legal Perspective.” Indian Defence Review, February 1. http://www.indiandefencereview.com/spotlights/augmented-soldier-ethical-social-legal-perspective/.

…

See bulls Paipetis, Stepfanos, 131 Palaephatus, 34, 66, 70, 72, 75 Pan, 162, 200 Panathenaia, 124 Pandareus, 142 Pandora, 156–78; Athenian popularity of, 170–72; beauty of, 156, 158; fabricated nature and characteristics of, 160; gifts given to, 156, 158–59; Hephaestus’s creation of, 1, 2, 23, 123, 155, 156–64, 157, 170–72, 215; images of, 157, 159, 161, 163–65, 167, 171; jar of, 156, 158, 160–61, 172–76; legacy of, 169–70; philosophical questions raised by, 123; as punishment for humankind, 156–58, 160–61, 172; reproductive capability of, 143, 242n10; smile of, 166 Panofka, Theodor, 162–63 Pan Painter, lekythos with Argus, 137 Paphos, 108 Parrhasius, 98, 111 Parthenon, Athens, 124, 170 Pasiphae, 67, 70–72, 73, 74, 142, 181, 185 Pataliputta, India, 203–5, 207 Paterculus, Arruntius, 184 patriarchy, 157 Pausanias, 13, 19, 48, 69, 75, 90, 106, 121, 128, 149, 171, 191 Pecse, 139 Pegasus, 139 Peitho, 159 Pelias, 33, 35–40, 37, 38, 40, 41, 53, 89 Pelops, 68 Penelope, 46, 57 Penthesilea Painter, 162; red-figure cup with Eos and Tithonus, 54 Peplos Kore, 168 Perilaus, 182–87, 185 Phaeacian ships, 151 Phalaris, 182–87, 185 phantasias (paintings with special effects), 98, 131 pharmaka, drugs, 9, 11, 13, 17, 33–38, 41, 62–64, 144 Phidias, 92, 170, 191 Philip II of Macedonia, 195 Philippus, 91, 93 Philo of Byzantium, 145–46, 190, 199–200, 202 Philostephanus of Alexandria, 108 Philostratus, 70, 95, 145, 149 Photius, 121 Pindar, 20, 21, 23, 47, 48, 94, 149, 176, 183, 186 plaster casts, 98 Plato, 48, 58, 61, 92, 122–23, 124, 190, 192, 244n41; Republic, 153, 190 Pliny the Elder, 48–49, 86, 97–98, 100, 109, 111, 121, 171, 183, 187, 199 Plutarch, 19, 28, 95, 183 Poliorcetes, Demetrius, 195 Pollux (hero). See Castor and Pollux Pollux (writer), 121 Polybius, 184, 192–94 Polybus, 27 Polydora, 109 Polyeidus, 48 Polygnotus, 13 Pomeroy, Sarah, 194 Pompeii, mural of Daedalus and Icarus, 79 Poniatowski, Stanislas, Prince, gems commissioned by, 157, 159 Popular Electronics (magazine), 31 pornography, 71. See also sexual activity Porus, King, 66–67 Poseidon, 144 Posidonius, 193 Praxiteles, 110; Aphrodite at Knidos, 109 Prester John, 49 Proclus, 199 Procris, 142 “programmed” devices, early, 7, 200, 247n41 Prometheus: in ancient literature, 105; as artificer, 2; Athenians’ veneration of, 124; bleeding ichor on the ground, 64; as creator of human race, Plate 10, Plate 11, 105–6, 112, 113, 114–27, 115, 117, 119, 120, 156; Daedalus confused/compared with, 103–4; on Etruscan gems (Prumathe), 115; immortality of, 43, 51, 228n4; legacy of, 124–25; and Pandora, 215; Parrhasius’s painting of, 98; punishment of, 43, 51, 63, 98, 126–27, 156, 228n4; technology and fire provided to humans by, 1, 9, 57, 61–63, 105, 124, 176 prosthetic body parts, 68–69 Protesilaus, 43, 109 Prumathe.

Aiming High: Masayoshi Son, SoftBank, and Disrupting Silicon Valley

by

Atsuo Inoue

Published 18 Nov 2021

As an aside, there was another young man who’d had an identical Damascene moment just like Son when he discovered the existence of the single-chip microcontroller. That young American was none other than Bill Gates, founder of Microsoft. Similar to Son, Gates would recall that in 1974, during his second year in university, he picked up a copy of Popular Electronics and was completely blown away by what he was reading. In an interview for this book, Gates described his own life-changing encounter as follows: ‘I was genuinely moved. In my opinion, Popular Electronics completely changed the relationship between humans and computers.’ The article in question would have appeared quite small and inconsequential to your average reader, announcing the launch of the $350 Altair computer kit manufactured by MITS, a company based in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

…

Son stuttered and his voice cracked with excitement as he told Masami after passing his standardised tests that he was going to enrol at Holy Names too. And there was another life-changing encounter in store for Son, a chance meeting of the most serendipitous kind. Whilst out doing the big shop at his local Safeway, Son happened to be flicking through a copy of Popular Electronics magazine when a close-up of the recently announced Intel 8080 computer chip (a microprocessor capable of processing eight-digit numbers consisting of 0s and 1s, which would give birth to the personal computer as we know it today) caught his eye. Son had never been so impressed in his entire life.

Outliers

by

Malcolm Gladwell

Published 29 May 2017

If you talk to veterans of Silicon Valley, they'll tell you that the most important date in the history of the personal computer revolution was January 1975. That was when the magazine Popular Electronics ran a cover story on an extraordinary machine called the Altair 8800. The Altair cost $397. It was a do-it-yourself contraption that you could assemble at home. The headline on the story read: “PROJECT BREAKTHROUGH! World's First Minicomputer Kit to Rival Commercial Models.” To the readers of Popular Electronics, in those days the bible of the fledgling software and computer world, that headline was a revelation. Computers up to that point had * The sociologist C .

Microchip: An Idea, Its Genesis, and the Revolution It Created

by

Jeffrey Zygmont

Published 15 Mar 2003

Hobbyists and other electro-enthusiasts were already in thrall of the idea that they could own their own private computer when Koplow started putting personal machines to work in offices in the mid- 1970s. Mail-order computer kits from the likes of Altair and Osborn are commonly considered the predecessors of today's ubiquitous personal computer. The accepted genealogy is frequently recited: A coupon ad for the Altair 8800 appeared in the January 1975 edition of Popular Electronics; the Apple I arrived in 1976; Radio Shack and Commodore topped Apple with more manageable machines; IBM introduced its personal computer in 1981, called the PC in an appropriation of the entire category's title for IBM's particular brand. But those presumed progenitors of popular computing did not feint toward popularity.

…

Philadelphia Storage Battery Company, 29 Philco, 29, 43, 53 Philip Hankins Inc. (PHI), 180, 184, 190 Phipps, Charlie, 70 Planar transistors, 38-39, 40, 51-57 and patents, 41-48 See also Transistors Plaza Suite, 178 Pocket calculators, 76-80, 83-99, 99-103. See also Calculators Police radios, 157 Pontiac Grand Am, 212 Popular Electronics, 198 Portable calculators, 83-87, 101, 104, 110, 134 cost of, 102-103 See also Calculators Portable phones, 161 Pravda, 169 Presley, Elvis, 79 Probst, Gary, 138 Proceedings of the IEEE (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers), 82 Product Engineering magazine, 174 Project Mercury, 10 Pulsar watch, 148-149 Radarange, 144-145, 147, 152 Radio Engineering (Terman), 87 Radio phones, 162-164 Radios, 62, 78-79, 147, 149 car, 204 mobile, 159 multichannel, 157-158 police, 157 two-way, 156-165 walk-and-talk, 157-158 Index 243 Radio Shack, 198 Radio waves, 161 Ralls, John, 42 RAM.

The Dream Machine: J.C.R. Licklider and the Revolution That Made Computing Personal

by

M. Mitchell Waldrop

Published 14 Apr 2001

He'd always been interested in digital electronics, he later ex- plained, and he'd been wanting to try his hand at building a minicomputer any- way. He proceeded to rough out a design using the Intel 8080, which he'd decided was by far the best chip available. And by midyear he was ready to ap- proach the editors of Popular Electronics, where he'd been an occasional contribu- tor, to ask if they'd like to feature his kit as a construction project. They would. The magazine was Radio-Electronics's arch rival, and technical ed- itor Les Solomon just loved the idea of an 8080-based computer project that would top the Mark-8 story.

…

Solomon, mean- while, came up with the perfect name for the machine. (Looking for ideas, he asked his daughter, Lauren, what they called the computer on Star Trek. "Com- puter," she replied. But she added that the starship Enterprise was headed for the star Altair that night, so why not call it that?) The now-famous January 1975 issue of Popular Electronics hit the newsstands in early December-ironically, just a month before George Heilmeier arrived at ARPA to make J. C. R. Licklider's life miserable. Since the only real, working Al- tair had gotten lost in transit before reaching the photographers in New York (it would turn up a year later), the cover showed the best mockup that MITS could manage on short notice: a pale-blue Altair shell with an impressive array of switches and diodes across the front that did absolutely nothing.

…

Basically, it was just one big array of slots for add-on cards: everything in the Altair was modular and replaceable. Even Roberts's later choice for an official programming language was reminis- cent of the minis. Created in the spring of 1975 by two young men who had been inspired by the Popular Electronics article-Bill Gates, now a Harvard under- grad, and his high school buddy Paul Allen, a programmer working outside Boston-Altair BASIC took a number of key features from DEC's BASIC for the PDP-11. (The language also owed its existence to the Harvard PDP-10, interest- ingly enough. Since Gates and Allen didn't have access to an Intel 8080 at the time, they used Gates's student account on the big machine to create a simula- 432 THE DREAM MACHINE tion of the microprocessor-in the process burning up some forty thousand dol- lars' worth of computer time that was not supposed to be used for commercial purposes.

Track Changes

by

Matthew G. Kirschenbaum

Published 1 May 2016

Disks themselves were literally floppy—5¼- or 8-inch black squares that actually waggled up and down; the smaller 3½-inch floppies (which were not floppy but rigid) did not yet exist. Hard drives existed, but were seen only rarely on the sorts of machines most consumers would buy. Time magazine was still more than a year away from declaring the personal computer its “Machine of the Year.” Popular Electronics had featured the Altair 8800—usually considered the world’s first microcomputer—on its cover in January 1975, but in 1981 was still a year away from renaming itself Computers and Electronics. Tron and War Games had not yet made it to movie theaters, and William Gibson had not yet coined the term “cyberspace” in his fiction.

…

While the story about Xerox’s failure to effectively commercialize those ideas is well known, the sequence of events behind the actual systems and their development is complex, involving multiple generations of hardware and software.15 The computer that Jobs famously saw demonstrated at PARC in 1979 (by none other than Larry Tesler, who had by then been working there for the past six years) was called the Alto, which had been prototyped as early as 1973.16 The Xerox Alto is not to be confused with the Altair 8800, the machine that famously graced the cover of Popular Electronics in January 1975 and (so the story goes) motivated Bill Gates to leave Harvard. (The Altair communicated its output to users, not on a screen or even on paper, but through gnomic blinking LED lights, the epitome of the “digital black-magic box” mentioned by the Homebrew Computer Club.)17 Unlike the Altair, then, the Alto was a fully functioning graphical computer system, years ahead of its time.

…

(magazine), 151, 152, 320n50 MTV, 52, 198 Mullaney, Tom, 252n9 MULTIVAC, 93 Munro, Alice, 208 Murakami, Haruki, 192–194, 311n39 Murdoch, Iris, 44 Naked Lunch (film), 17 NEC PC-8500, 231 Nelson, Ted, 24, 105, 121, 127, 292n8 Netscape Navigator, 27 Nevala-Lee, Alec, 254n17 New England Review / Bread Loaf Quarterly, 139, 253n17 New York (magazine), 151 New Yorker, 71, 86, 88, 132, 208 Nexus (word processor), 111 Nicholls, David, 238 Nietzsche, Friedrich, ix, 10, 243, 256n34 Niven, Larry, 20, 35, 95, 99, 102, 216, 286n44 NLS (oNLine System), 120–123, 125, 128 Noland, Carrie, 199, 313n65, 320n60 North Star Horizon II, 93, 117 Norton, Andre (Alice), 113 Norton, Peter, 208 Nota Bene (program), 26, 236 O’Brien, Connor (Tomas), 320n67 O’Neill, Joseph, 27 O’Kane Mara, Miriam, 264n77 Oates, Joyce Carol, 21, 22, 27, 264n80 Odyssey Corrections (ODYCOR), 68 Olivetti, 21, 48, 90, 91, 117, 183, 207, 236, 252n11 Olympia, 9, 13, 21, 108, 261n48 Ondaatje, Michael, 22, 27 Ong, Walter J., 79, 158 Optek, 72 Orwell, George, xiv, 137, 232 Osborne, Adam, 63 Osborne 1, 25, 50, 63, 73, 118, 217, 222, 273n84, 277n54 OULIPO, 38 Oz, Amos, 20 Palo Alto Research Center (PARC), 122, 123, 125–130, 195, 235, 276n41, 292n15 Parfit, Michael, 207 Paris Review, xiv, 23, 27, 72, 114, 138, 159, 191 Patterson, James, 42–44, 270n50 Paul, Barbara, 94 Perfect Software, 63, 65 Perfect Writer, 33, 63, 64, 65, 113, 142 Perfectionism, 35–41, 43, 49, 59, 67, 180, 274n88 Perfectly Simple, 142 Peterson, W. E. Pete, 266n2 Philips “Carry Corder,” 179 Phillips, Tom, 191 Pietsch, Michael, 222 Pinsky, Robert, 7 Plant, Sadie, 298n33 PLATO, 159 Playboy, 77, 167, 279n9 Plimpton, George, 27 Pohl, Frederick, 3, 265n88 Polt, Richard, 18, 327n39 Polymorphic, 117 Popular Electronics (magazine), 51, 123 Poster, Mark, 5, 6 Post-structuralism, 5, 189 Pound, Ezra, 28, 227 Pournelle, Jerry, 95–103, 107, 109–110, 129, 137, 141, 188, 195, 216–218, 228, 284n18, 284n26, 285n28, 285n33, 286n45, 301n75 Powers, Richard, 158–159 Pratchett, Terry, 111 Price, Ken, 209, 210 Price, Leah, 167, 182 Printing, 50, 67, 106, 129, 161, 212 Processed World, 154, 300n59 Profiles (magazine), 65, 66, 219, 277n58 PROGRAMAP, 106–107, 128 Proulx, Annie, 22 Pynchon, Thomas, xv, 86, 253n14 Quark (application), 30, 203 Queneau, Raymond, 268n29 Radio Shack, 56, 78, 92, 207, 241, 287n52 Rainey, Lawrence, 26, 233, 322n94 RAND editor, 134 Ray, Karen, 37 Reagan, Ronald, 41, 52 Redactron Corporation, 149–155, 180, 240; Data Secretary, 150–152, 236 Reed, Courtney, 281n42 Remington, ix, 160, 164, 201, 282n2 Research in Word Processing Newsletter, 25 Reside, Doug, 26 Rice, Anne, 3, 50, 161, 185, 208, 273n84, 274n88, 316n11 Rinearson, Peter, 236 Roberts, Robin, 288n85 Robinson, Frank M., 117 Rogers, Samuel, 14 Rose, Joel, 196 Rose, Jonathan, xii Ross-MacDonald, Malcolm, 117, 291n118 Roth, Henry, 187–188, 309n15 Roth, Philip, 226, 229 Rothman, David H., 278n77 Rowling, J.

Showstopper!: The Breakneck Race to Create Windows NT and the Next Generation at Microsoft

by

G. Pascal Zachary

Published 1 Apr 2014

Sitting in his room, he often considered his future, “being a philosophical, depressed guy, trying to figure out what I was doing with my life.” In December 1974, he received a clue from Paul Allen, a high school pal three years his senior. Allen, who had helped Gates build the traffic device, arrived at Harvard one day with the latest issue of Popular Electronics. On the cover of its January 1975 issue the magazine touted a computer named the Altair. It was a hobbyist’s dream. For less than two thousand dollars the Altair packed the power of a computer costing anywhere from ten to one hundred times as much. The secret? The Altair was powered by a microprocessor.

…

The PC was like an automobile; it would go anywhere its driver wanted. Instead of organizing work around the mainframe’s schedule, a person with a PC could do computing anytime. The PC’s promoters saw its radical appeal. It turned the blandly efficient computer into a consumer product. As the editors of Popular Electronics declared when introducing the Altair, “The era of the computer in every home... has arrived!” These words intoxicated Gates and Allen, who saw a gaping hole in the Altair: It came without software. Buyers had to write their own, or they were stuck, essentially, with a useless machine. This was something Gates and Allen could fix.

Korea--Culture Smart!

by

Culture Smart!

Published 15 Jun 201

The seaside temple of Haedong in Busan, South Korea. SHOPPING Shopping can be great fun in South Korea, whether in the big cities, with their smart department stores and numerous markets, or in small local markets. Leather and brass products are of a high standard. The range of goods available is huge, with electronic goods especially popular. Electronic goods can be purchased at very competitive prices at Yongsan Electronics Market in Seoul, a hub of more than 5,000 electronics stores spread across twenty buildings. Country markets may specialize in excellent traditional products, such as the bamboo goods at the village of Tamyang in South Cholla province.

Billionaire, Nerd, Savior, King: Bill Gates and His Quest to Shape Our World

by

Anupreeta Das

Published 12 Aug 2024

They have a certain bravado that others don’t.” When Gates entered Harvard University in 1973, the first cheap desktop computers were coming to market, made possible by advances in chip technology. But they needed software to become functional. As the Microsoft legend goes, Allen happened to read in Popular Electronics that the makers of a microcomputer called the MITS-Altair were looking for a programming language that could run on their hardware. The Altair was a foot and a half tall, and nearly as wide. After Allen told Gates excitedly about the opportunity, they decided to make a pitch—without having written a single line of code.

…

We’re Not Ready, The” (Gates), 246–247 NIAID (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases), 175, 248 Nick Carraway (fictional character), 281 NIH (National Institutes of Health), 177, 182 Nike, 139 Nikolic, Boris, 229, 231, 235 Nilekani, Nandan, 196 Nobel Peace Prize, 103–105 Nocera, Joseph, 75 Nordstrom, 153 Nordstrom family, 267 North American Review, The, 120 Norton Museum of Art, 270 No Such Thing as a Free Gift (McGoey), 185 Novak, Molly, 145 Nvidia, 44 Obama, Barack, 110, 182, 245, 255, 264 Obama, Michelle, 167 Obama Foundation, 167–168 Ocasio-Cortez, Alexandria, 258, 260 #occupywallstreet, 255 Occupy Wall Street movement, 134, 255 Ohio State University, 252 Oklahoma City bombing, 245 Omaha World-Herald, 115 O’Mara, Margaret, 67–68, 73, 83–84 Omega Advisors, 260 Omidyar, Pierre, 204 Omidyar Network, 204 ONE (philanthropic organization), 100 Oneness vs the 1% (Shiva), 190 Only the Paranoid Survive (Grove), 69 Opel, John, 35 OpenAI, 56, 87 OpenSecrets, 85, 272 Open Society Foundations, 202, 272 “Optimist, The” (newsletter), 276 Oracle, 40–41, 72 OS/2 operating system, 70 Otter Tail Power, 212 Oxfam International, 253 Oxford University, 178 Page, Larry, 44, 45, 83, 139 Pakistan, 278 Pao, Ellen, 57 Pasic, Amir, 202 patent licensing firms, 222 PATH (global health organization), 98 Patriotic Millionaires, 260 pay discrimination, 238–243 PayPal, 44, 56, 272 PBS, 243, 262 PBS NewsHour, 234 Pendrell, 223 Penn, Mark, 94–95 Penn, Sean, 204 Penny Finance, 165 Perel, Esther, 164 Perelman, Ron, 236 “per processor” contracts, 71 Perry, Matthew, 65 personal alliances, 56 Pew Research Center, 251 philanthropy, 21–29, 97–113, 174–206 Pichai, Sundar, 10, 13, 18, 82 Piketty, Thomas, 256–257 PIMCO, 136 Pingali, Prabhu, 126–127 Pittsburgh, Pa., 89–90 Pivotal Ventures, 153–154, 165–171, 204, 239 Playboy, 46, 69, 156 Plutocrats (Freeland), 179 Pogue, David, 103 polio, 198 polio research, 276–278 Politico, 177, 258, 260 Pollock, Jackson, 270 polls and polling, 94–95, 128, 196, 246, 251–252, 258 see also individual polls, e.g., YouGov popular culture, 50–54 Popular Electronics, 34 PowerPoint, 70 Predators’ Ball, The (Bruck), 40 Princeton University, 37, 67, 264, 267 Principles (Dalio), 17 Pritzker, Tom, 236 Pritzker family, 263 Program on Inequality and the Common Good, 261 Project Syndicate, 192 ProPublica, 272, 274 public relations, 81–84 Pulitzer, Joseph, 24 Pulitzer Prize, 40 Purdue Pharma, 28 Putnam Investments, 209–210 QAnon, 246 Quartz, 239 Questlove, 107 Quicken, 72 Radar magazine, 237 rage giving, 22 Raikes, Jeffrey, 222, 268 Randolph, Marc, 44 Ravitch, Diane, 187 Reagan, Ronald, 100 Real Anthony Fauci, The (Kennedy), 248 RealClear Opinion Research, 18, 251 Reback, Gary, 63, 73–74, 76–78 Reddit, 108, 250 Reich, Rob, 187 Reno, Janet, 71 Republic Services, 212, 220 Revenge of the Nerds (film), 51 Rich, Frank, 96 Richards, Keith, 65 Riffle, Dan, 258 Rihanna, 204 Rinearson, Peter, 75 RJR Nabisco, 40 Road Ahead, The (Gates), 75 Robbins, Tim, 94 Roberts, Ed, 34 Robertson, Channing, 50 Robert Wood Johnson foundation, 128 Rockefeller, David, 132 Rockefeller, John D., Sr., 15, 20, 62–64 Rockefeller Foundation, 176, 182, 192, 197–198, 280 Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors, 141, 186 Rocket Mortgage, 273 Rød-Larsen, Terje, 105 Roe v.

Code: The Hidden Language of Computer Hardware and Software

by

Charles Petzold

Published 28 Sep 1999

Other product and company names mentioned herein may be the trademarks of their respective owners. Images of Charles Babbage, George Boole, Louis Braille, Herman Hollerith, Samuel Morse, and John von Neumann appear courtesy of Corbis Images and were modified for this book by Joel Panchot. The January 1975 cover of Popular Electronics is reprinted by permission of Ziff-Davis and the Ziff family. All other illustrations in the book were produced by Joel Panchot. Unless otherwise noted, the example companies, organizations, products, people, and events depicted herein are fictitious. No association with any real company, organization, product, person, or event is intended or should be inferred

…

Despite neither method being intrinsically "right," the difference does create an additional incompatibility problem when sharing information between systems based on little-endian and big-endian machines. What became of these two microprocessors? The 8080 was used in what some people have called the first personal computer but which is probably more accurately the first home computer. This is the Altair 8800, which appeared on the cover of the January 1975 issue of Popular Electronics. When you look at the Altair 8800, the lights and switches on the front panel should seem familiar. This is the same type of primitive "control panel" interface that I proposed for the 64-KB RAM array in Chapter 16. The 8080 was followed by the Intel 8085 and, more significantly, by the Z-80 chip made by Zilog, a rival of Intel founded by former Intel employee Federico Faggin, who had done important work on the 4004.

The Rise of the Network Society

by

Manuel Castells

Published 31 Aug 1996

They gathered in loose groups, to exchange ideas and information on the latest developments. One such gathering was the Home Brew Computer Club, whose young visionaries (including Bill Gates, Steve Jobs, and Steve Wozniak) would go on to create in the following years up to 22 companies, including Microsoft, Apple, Comenco, and North Star. It was the club’s reading, in Popular Electronics, of an article reporting Ed Roberts’s Altair machine which inspired Wozniak to design a microcomputer, Apple I, in his Menlo Park garage in the summer of 1976. Steve Jobs saw the potential, and together they founded Apple, with a $91,000 loan from an Intel executive, Mike Markkula, who came in as a partner.

…

New rules, aimed at encouraging electronic trading in the 1990s, allowed ECNs to post orders from their clients on Nasdaq’s system, and receive a commission when the order was filled. A large number of individual investors entered the stock market on their own, using the power of technology. The so-called day-traders, whose favorite investment targets were stocks of Internet companies, were the ones who really popularized electronic trading. They are called day-traders because they usually cash out at the end of the day, since they operate on small margins of change in the valuation of securities, and do not have financial reserves. Thus, they stay until they make a sufficient profit, by buying and selling on very short-term transactions – or until they have had enough losses for the day.128 According to the Securities Exchange Commission, on-line trading grew from less than 100,000 trades a day in mid-1996 to over half a million a day by the end of 1999.

…

place: interactivity; space of planar process Platonov, Andrey PNUD Poirer, Mark polarization; see also marginalization Policy Studies Institute politics; Asian Pacific; computer-mediated communication; corruption; global economy; globalization; media; Mexico; multimedia; personal interest; third way Polyakov, L. V. Pool, Ithiel de Sola Popular Electronics Porat, Marc Porter, Michael Portes, Alejandro Portnoff, Andre-Yves Postel, Jon post-Fordism post-industrialism Postman, Neil postmodernism Poulantzas, Nicos poverty Powell, Walter W. power Powers, Bruce R. Preston, Holly H. Preston, Pascal Prigogine, Ilya printing, China privatization Prodi, Romano producer networks producer services production; assembly line; capitalist; cross-border; flexibility; globalization; lean; networking; offshore; organization transformed; social relations; technology productivity; competitiveness; computer manufacturing; electronics; employment; globalization; G-7 countries; industrialism; innovation; knowledgebased; labor costs; Mexico; North/South; OECD countries; profitability; services; Solow; technology; time professionals profit-maximizing profitability: crisis; information technologies; productivity; US property rights property slump Pursell, Carroll Putnam, Robert Pyo, H.

Becoming Steve Jobs: The Evolution of a Reckless Upstart Into a Visionary Leader

by

Brent Schlender

and

Rick Tetzeli

Published 24 Mar 2015

Living there, a curious child interested in math and science could easily develop a much deeper sense of the leading edge of technology than those growing up elsewhere in the country. Electronics were just beginning to replace hot rods as the passion of young tinkerers. Geeks lived and breathed the fumes emanating from their soldering irons, and traded dog-eared copies of Popular Science and Popular Electronics magazines. They built their own transistor radios, hi-fi stereo systems, ham radios, oscilloscopes, rockets, lasers, and Tesla coils from kits offered by mail order companies like Edmund Scientific, Heathkit, Estes Industries, and Radio Shack. In Silicon Valley, electronics wasn’t just a hobby.

…

No surprise, then, that the industry had become cloistered and a little complacent. Out in California a significant number of the people who would have a hand in flipping that industry on its head started meeting regularly as a hobbyist group called the Homebrew Computer Club. Their first get-together occurred shortly after the publication of the January 1975 issue of Popular Electronics, which featured a cover story about the Altair 8800 “microcomputer.” Gordon French, a Silicon Valley engineer, hosted the gathering in his garage to show off an Altair unit that French and a buddy had assembled from the $495 kit sold by Micro Instrumentation and Telemetry Systems (MITS). It was an inscrutable-looking device, about the size of a stereo component amplifier, its face sporting two horizontal arrays of toggle switches and a lot of blinking red lights.

So Good They Can't Ignore You: Why Skills Trump Passion in the Quest for Work You Love

by

Cal Newport

Published 17 Sep 2012

It was with this mindset that later that same year, Jobs stumbled into his big break. He noticed that the local “wireheads” were excited by the introduction of model-kit computers that enthusiasts could assemble at home. (He wasn’t alone in noticing the potential of this excitement. When an ambitious young Harvard student saw the first kit computer grace the cover of Popular Electronics magazine, he formed a company to develop a version of the BASIC programming language for the new machine, eventually dropping out of school to grow the business. He called the new firm Microsoft.) Jobs pitched Wozniak the idea of designing one of these kit computer circuit boards so they could sell them to local hobbyists.

AC/DC: The Savage Tale of the First Standards War

by

Tom McNichol

Published 31 Aug 2006

Flushed with success, Edison looked forward to the day when DC would power not only electric cars but also the engines of heavy industry. AC power plants would eventually become something akin to filling stations, used to recharge Edison’s DC batteries. In the AC/DC war, the victor would become the vanquished, and Edison would be proven right after all. In a 1910 article for Popular Electronics, Edison wrote, “For years past I have been trying to perfect a storage battery, and have now rendered it entirely suitable to automobile and other work. Many people now charge their own batteries because of lack of facilities, but I believe central stations will find in this work very soon the largest part of their load.

Deep Work: Rules for Focused Success in a Distracted World

by

Cal Newport

Published 5 Jan 2016

The approach suggested here responds aggressively to both issues—you send fewer e-mails and ignore those that aren’t easy to process—and by doing so will significantly weaken the grip your inbox maintains over your time and attention. Conclusion The story of Microsoft’s founding has been told so many times that it’s entered the realm of legend. In the winter of 1974, a young Harvard student named Bill Gates sees the Altair, the world’s first personal computer, on the cover of Popular Electronics. Gates realizes that there’s an opportunity to design software for the machine, so he drops everything and with the help of Paul Allen and Monte Davidoff spends the next eight weeks hacking together a version of the BASIC programming language for the Altair. This story is often cited as an example of Gates’s insight and boldness, but recent interviews have revealed another trait that played a crucial role in the tale’s happy ending: Gates’s preternatural deep work ability.

Smartcuts: How Hackers, Innovators, and Icons Accelerate Success

by

Shane Snow

Published 8 Sep 2014

A superwave can show up on a regular surf day when random smaller waves align. When that happens, the only people who can possibly ride it are the ones who actually went to the beach that day. The ones who actually got in the water. BY THE END OF 2012 Google’s Gmail service had become the most popular electronic mail provider in the world. That same year, Google’s AdSense product accounted for more than $12 billion in revenue, about a quarter of the search giant’s total revenues. Each of those products—smart electronic mail and context-based advertising—caught an enormous wave when it launched. Like Twitter, as we learned in chapter 4, both Gmail and AdSense started off as side projects.

Fatal System Error: The Hunt for the New Crime Lords Who Are Bringing Down the Internet

by

Joseph Menn

Published 26 Jan 2010

Once an insider wagered, the bookies knew how to bet themselves. As Darren Rennick explained it to Barrett, sports stars often bet against themselves. Then Mickey would adjust the line on the odds and secretly bet the same way as the athlete at other, unsuspecting sportsbooks. In the increasingly popular electronic poker and casino games, much of the play seemed harmless for non-addicts. The new games were wonderful for the sportsbooks, though, because they could be played at any time, while betting on sporting events built toward a specific date and hour. BetCRIS and others urged winning sports bettors to try their luck at the poker tables, where they often lost everything back.

Americana: A 400-Year History of American Capitalism

by

Bhu Srinivasan

Published 25 Sep 2017

• • • IN THE SUMMER of 1975, in Albuquerque, New Mexico, unit 114 in the Portals apartment complex was becoming increasingly crowded. The formation of this makeshift operation could be traced back a few months earlier to a newsstand on the East Coast. It was early winter in Cambridge, Massachusetts, when two old high school friends from Seattle excitedly pored over the January edition of Popular Electronics magazine. The magazine had partnered with a small builder of electronic components to offer a build-it-yourself computer kit called the Altair, named for a fictional destination from an episode of Star Trek. One of the young men, Bill Gates, was in his freshman year at Harvard, and Paul Allen was visiting.

…

The pair quickly hired several of their programmer friends to move into Allen’s apartment for the summer, with Gates joining when spring classes ended at Harvard. When September came around, Gates decided to stay. The Altair, at the time, was causing significant excitement among early adopters—enthusiasts known as hobbyists—including some in Silicon Valley. At the Homebrew Computer Club, formed just weeks after the Popular Electronics issue premiered the Altair, Steve Wozniak made it to the first meeting, which he would later call “one of the most important nights” of his life. There he saw the Altair demonstrated, beginning to understand the implications and flexibility of low-cost microprocessors. Wozniak spent the next few months hacking together the functions of a keyboard and a microprocessor that could show keystrokes on a television screen—which, in Wozniak’s telling, was an achievement that had never been accomplished outside large corporate mainframes costing tens or often hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Americana

by

Bhu Srinivasan

• • • IN THE SUMMER of 1975, in Albuquerque, New Mexico, unit 114 in the Portals apartment complex was becoming increasingly crowded. The formation of this makeshift operation could be traced back a few months earlier to a newsstand on the East Coast. It was early winter in Cambridge, Massachusetts, when two old high school friends from Seattle excitedly pored over the January edition of Popular Electronics magazine. The magazine had partnered with a small builder of electronic components to offer a build-it-yourself computer kit called the Altair, named for a fictional destination from an episode of Star Trek. One of the young men, Bill Gates, was in his freshman year at Harvard, and Paul Allen was visiting.

…

The pair quickly hired several of their programmer friends to move into Allen’s apartment for the summer, with Gates joining when spring classes ended at Harvard. When September came around, Gates decided to stay. The Altair, at the time, was causing significant excitement among early adopters—enthusiasts known as hobbyists—including some in Silicon Valley. At the Homebrew Computer Club, formed just weeks after the Popular Electronics issue premiered the Altair, Steve Wozniak made it to the first meeting, which he would later call “one of the most important nights” of his life. There he saw the Altair demonstrated, beginning to understand the implications and flexibility of low-cost microprocessors. Wozniak spent the next few months hacking together the functions of a keyboard and a microprocessor that could show keystrokes on a television screen—which, in Wozniak’s telling, was an achievement that had never been accomplished outside large corporate mainframes costing tens or often hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Are We Getting Smarter?: Rising IQ in the Twenty-First Century

by

James R. Flynn

Published 5 Sep 2012

In other words, WISC arithmetic tests for the kind of mind that is comfortable with mathematics and therefore, likely to ind advanced mathematics congenial. No progress on this subtest signals why by the 12th grade, American schoolchildren cannot do algebra and geometry any better than the previous generation. We turn to the worlds of leisure and popular entertainment. Greenield (1998) argues that video games, popular electronic games, and computer applications require enhanced problem solving in visual and symbolic contexts. If that is so, that kind of enhanced problem solving is necessary if we are fully to enjoy our leisure. Johnson (2005) points to the cognitive demands of video games, for example, the spatial geometry of Tetris, the engineering riddles of Myst, and the mapping of Grand Theft Auto.

The Entrepreneurial State: Debunking Public vs. Private Sector Myths

by

Mariana Mazzucato

Published 1 Jan 2011

And why is the State not rewarded for its direct investments in basic and applied research that lead to successful technologies that underpin revolutionary commercial products such as the iPod, the iPhone and the iPad? The ‘State’ of Apple Innovation Apple has been at the forefront of introducing the world’s most popular electronic products as it continues to navigate the seemingly infinite frontiers of the digital revolution and the consumer electronics industry. The popularity and success of Apple products like the iPod, iPhone and iPad have altered the competitive landscape in mobile computing and communication technologies.

You Are Here: From the Compass to GPS, the History and Future of How We Find Ourselves

by

Hiawatha Bray

Published 31 Mar 2014

Lawrence Freedman, The Evolution of Nuclear Strategy (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 1989), 24. 23. Ibid., 335. 24. Ibid., 378–406. 25. Michael S. Nolan, Fundamentals of Air Traffic Control (Clifton Park, NY: Cengage Learning, 2010), 75–77. See also Art Zuckerman, “Doppler Radar Charts the Airlanes,” Popular Electronics, May 1959, 41. 26. “Inertial for the 747,” Flight International, September 4, 1969. 27. MacKenzie, Inventing Accuracy, 180–182. Chapter 4 1. Matthew Brzezinski, Red Moon Rising: Sputnik and the Hidden Rivalries That Ignited the Space Age (New York: Macmillan, 2007), 161–187. 2. William H.

Python for Algorithmic Trading: From Idea to Cloud Deployment

by

Yves Hilpisch

Published 8 Dec 2020

Real-time data Algorithmic trading requires dealing with real-time data, online algorithms based on it, and visualization in real time. The book provides an introduction to socket programming with ZeroMQ and streaming visualization. Online platforms No trading can take place without a trading platform. The book covers two popular electronic trading platforms: Oanda and FXCM. Automation The beauty, as well as some major challenges, in algorithmic trading results from the automation of the trading operation. The book shows how to deploy Python in the cloud and how to set up an environment appropriate for automated algorithmic trading.

Enshittification: Why Everything Suddenly Got Worse and What to Do About It

by

Cory Doctorow

Published 6 Oct 2025

If, one winter day, an unscrupulous gas-station owner espies someone leaving a vehicle stranded in the snow and trudging toward his station, he’d still need an army of helpers to reprice all the snow chains before that stranded traveler can make it through the door. But a digital business can change everything, all the time, instantly, based on automated processes that act on surveillance data and other information. Tech suppliers are doing everything they can to bring twiddling to the “real” world. Take the increasingly popular electronic shelf labels popping up in grocery stores. These e-ink displays are networked and can adjust the price of everything in a given store, or in all the stores in a chain, at the click of a mouse. In Norway, where electronic shelf labels are popular, some merchants “adjust” prices more than two thousand times per day.

Dark Pools: The Rise of the Machine Traders and the Rigging of the U.S. Stock Market

by

Scott Patterson

Published 11 Jun 2012

Coils of wires, Ethernet cables, and power cords snaked in all directions, finding egress into weird openings in the floors, walls, and ceiling—or just disappearing into mounds of trash. Trash was everywhere—on the racks, the tables, perched atop PCs. Mostly, of course, it was on the floor. The floor was trash. Chunks of ancient candy bars, apple cores, blackened orange peel, coffee grounds. Stacks of Popular Electronics and Investors Business Daily. An oscilloscope. Milk cartons. Mostly empty plastic Coke bottles. Computer keyboards, several broken. An eighteen-inch lizard named Greg sat in a giant climate-controlled terrarium. The door often couldn’t be closed because of the creeping clutter. With space so tight, Levine usually stood, furiously typing on several keyboards hooked to Dell computer towers.

Coding Freedom: The Ethics and Aesthetics of Hacking

by

E. Gabriella Coleman

Published 25 Nov 2012

Unix was growing increasingly popular among geeks all over the world, and as Kelty (2008) has shown, was already binding geeks together in what he identifies as a recursive public—a public formed by discussion, debate, and the ability to modify the conditions of its formation, which in this case entailed creating and modifying software. Stallman (1985, 30) formulated and presented his politics of resistance along with his philosophical vision in “The GNU Manifesto,” originally published in the then-popular electronics magazine Dr. Dobb’s Journal: I consider that the golden rule requires that if I like a program I must share it with other people who like it. Software sellers want to divide the users and conquer them, making each user agree not to share with others. I refuse to break solidarity with other users in this way.

What the Dormouse Said: How the Sixties Counterculture Shaped the Personal Computer Industry

by

John Markoff

Published 1 Jan 2005

In the Whole Earth Catalog spirit, Tesler’s activist neighbor argued with him that people were eventually going to build their own computers. Tesler wasn’t so sure about that, but when he saw an advertisement in the local paper announcing the visit of a van to Palo Alto to show off the new MITS Altair 8800 computer kit, he thought he would go take a look. It had been only six months since Popular Electronics magazine had published a cover story on the Altair, a blue-edged metal box with lights and switches and not much else. Now the Albuquerque, New Mexico, company that manufactured it was sending a bus on tour around the country to demonstrate it. Tesler went over to Rickey’s Hyatt House Hotel on El Camino Real in Palo Alto to attend the presentation, and though he hadn’t been very impressed with the machine, he went straight back to Xerox and said, “I just saw something really important.”

Empire of the Sum: The Rise and Reign of the Pocket Calculator

by

Keith Houston

Published 22 Aug 2023

Elaine Smay, “A Wristwatch That Sums It Up,” Popular Science 208, no. 4 (April 1976): 54. 42 “Pulsar Jeweler’s Technical Manual,” 3. 43 Ball, “The Pulsar Calculator Watch.” 44 Guy Ball, “The Hughes Aircraft Company LED Modules and Calculator Watch,” LED Watches, 2004, https://web.archive.org/web/20150819061625/http://www.ledwatches.net/articles/Hughes Aircraft Company’s Calculator Watch.htm; “Compuchron Hughes Aircraft LED 1973,” accessed November 12, 2021, http://www.crazywatches.pl/compuchron-hughes-aircraft-led-1973; Adam Harras, “Hughes Aircraft (Aka Timeulator),” Digital Watch, accessed November 18, 2021, http://www.digital-watch.com/DWL/1work/hughes-calculator-watch-1977. 45 David G. Hicks, “HP-01,” The Museum of HP Calculators, accessed November 18, 2021, https://www.hpmuseum.org/hp01.htm. 46 “Calculator Prices Continue to Plummet,” New Scientist, June 6, 1974. 47 “Demand for Calculator Chips Exceeds Supply,” Popular Electronics (New York: Ziff-Davis, September 1974); Nicholas Valéry, “Coming of Age in the Calculator Business,” New Scientist, November 13, 1975. 48 “ ‘Scary Boom’ in US Electronics,” New Scientist, November 1, 1973. 49 “Calculator Prices Continue to Plummet”; “Historical Rates - GBP to USD, 25 Dec 1974,” fxtop.com, accessed November 19, 2021, https://fxtop.com. 50 “Arab Oil Embargo,” Encyclopaedia Britannica (Chicago: Encyclopaedia Britannica, October 1, 2020), https://www.britannica.com/event/Arab-oil-embargo/; Department of Economic and Social Affairs, “World Economic Survey, 1975” (New York: United Nations, 1976), sec.

Boom: Bubbles and the End of Stagnation

by

Byrne Hobart

and

Tobias Huber

Published 29 Oct 2024

With careful troubleshooting and extensive effort—not to mention some soldering, as the computer was shipped as a box of parts—a diligent programmer could make the Altair display a sequence like “*” “****” “*********” “****************” (the first four perfect squares). While the personal computer was not yet particularly useful, the idea of a personal computer made waves. The Altair was featured on the cover of the magazine Popular Electronics in January 1975, which promptly led to a run on the Altair. It also caught the attention of a Harvard undergraduate, one William Henry Gates III. Gates, along with his childhood friend Paul Allen, promptly began working on a program that would make the Altair significantly more useful. They planned to create an implementation of the BASIC programming language to run on Altair machines that they hoped to sell directly to users.

Palo Alto: A History of California, Capitalism, and the World

by

Malcolm Harris

Published 14 Feb 2023

In 1974, the company was $365,000 in debt ($2 million in 2022 value), but Roberts had one advantage: He knew Intel’s forthcoming 8080 chip, significantly cheaper and more powerful than the 8008, was going to deliver a knockout punch. Roberts used imminent doom as a stepstool to the future, negotiating a bulk deal with Intel for 8080s and pivoting MITS to produce a DIY computer kit. The time had finally come, and Popular Electronics editor Les Solomon was determined to get a picture of the company’s product on the cover before another magazine announced an 8080 kit. When the prototype Roberts sent got lost in the mail, Solomon decided to trust the blueprints. Someone—accounts differ—named it the Altair, after the destination planet in an episode of Star Trek.iii In January of 1975, the personal computer era kicked into gear with the glossy national announcement of the Altair 8800, and mail orders, complete with hundreds and even thousands of dollars, poured into Albuquerque.2 Artisanal hippie entrepreneurialism was in the NorCal air, and not just among the early computer hackers: A three-man team led by two Stanford students started selling a beginner’s guide to “juggling for the complete klutz” in late-1970s Palo Alto, adding a second book on the official stoner sport Hacky Sack in 1982.

…

He needn’t have worried; when SAIL did get firebombed, in the early 1970s, no one was injured.24 Trey went away to Harvard, but only long enough to re-create his great-grandfather’s westward flight. Gates was entrepreneurially minded, and the computer industry was on the other side of the country, or at least its future was. He and Allen saw the Altair on the cover of Popular Electronics in January of 1975 with everyone else and drew a similar conclusion: The microcomputers were coming. Gates and Allen offered to translate a version of the programming language BASIC for MITS, built using an Intel 8080 emulator Allen whipped up on the much more powerful PDP-10, simulating the new category of microcomputer hardware on the minicomputer.

Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can't Stop Talking

by

Susan Cain

Published 24 Jan 2012

In walks an uncertain young man of twenty-four, a calculator designer for Hewlett-Packard. Serious and bespectacled, he has shoulder-length hair and a brown beard. He takes a chair and listens quietly as the others marvel over a new build-it-yourself computer called the Altair 8800, which recently made the cover of Popular Electronics. The Altair isn’t a true personal computer; it’s hard to use, and appeals only to the type of person who shows up at a garage on a rainy Wednesday night to talk about microchips. But it’s an important first step. The young man, whose name is Stephen Wozniak, is thrilled to hear of the Altair.

Tools for Thought: The History and Future of Mind-Expanding Technology

by

Howard Rheingold

Published 14 May 2000

It had an "instruction set" of "firmware" primitive commands built into it, an arithmetic and logic unit, a clock, temporary storage registers, but no external memory, no input or output devices, no circuitry to connect the components together into a working computer. Roberts decided to provide the other components and a method for interconnecting them and sell the kits to hobbyists. In January of 1975, Popular Electronics magazine did a cover story on "a computer you can build yourself for $420." It was called the Altair (after a planet in a Star Trek episode). Roberts was hoping for 200 orders in 1975, to keep the enterprise alive, and he received more than that with the first mail after the issue hit the stands.

The Everything Blueprint: The Microchip Design That Changed the World

by

James Ashton

Published 11 May 2023

Son’s father was a pig farmer who brewed illegal alcohol on the side but hauled himself up to enjoy success with restaurants and parlours specialising in pachinko, a Japanese version of pinball. In the summer of 1973, when he was 16, Son’s family was wealthy enough to send him to California to be educated. So the story goes, on a shopping trip to his local Safeway grocery store between language classes, he was flicking through a copy of Popular Electronics magazine when he happened upon a close-up picture of Intel’s newly announced 8080 chip, the antecedent of the x86 architecture that would come to dominate personal computers. Son related that it left a deep impression on him. ‘It was like when you watch a really powerful scene in a film or get caught up in a piece of music and you start tingling all over,’ he said.

Culture and Prosperity: The Truth About Markets - Why Some Nations Are Rich but Most Remain Poor

by

John Kay

Published 24 May 2004

It was eight years before they unveiled a commercial version. The new product impressed the trade press with its sophistication. But it was by then too idiosyncratic and expensive for the market. While Xerox was perfecting the Alto, personal computers were developed by hobbyists. The Altair minicomputer was advertised in Popular Electronics magazine in December 1974, a self-assembly kit with a price of$400. Two young Harvard students, Paul Allen and Bill Gates, devised a version of the programming language BASIC for the Altair. Toy computers followed, manufactured by companies such as Commodore, with memory provided by cassette tape recorders.

From Airline Reservations to Sonic the Hedgehog: A History of the Software Industry

by

Martin Campbell-Kelly

Published 15 Jan 2003