Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness

by

Richard H. Thaler

and

Cass R. Sunstein

Published 7 Apr 2008

In Georgia, for example, routine removal increased the number of corneal transplants from twenty-five in 1978 to more than one thousand in 1984.3 The widespread practice of routine removal of kidneys would undoubtedly prevent thousands of premature deaths, but many people would object to a law that allows government to take parts of people’s bodies when they have not agreed, in advance, to the taking. Such an approach violates a generally accepted principle, which is that within broad limits, individuals should be able to decide what is to be done with and to their bodies. Presumed Consent A policy that can pass libertarian muster by our standards is called presumed consent. Presumed consent preserves freedom of choice, but it is different from explicit consent because it shifts the default rule. Under this policy, all citizens would be presumed to be consenting donors, but they would have the opportunity to register their unwillingness to donate, and they could do so easily.

…

We want to underline the word easily, because the harder it is to register your unwillingness to participate, the less libertarian the policy becomes. Recall that libertarian paternalists want to impose low costs, and if possible no costs, on those who go their own way. Although presumed consent is, in a sense, the opposite of explicit consent, there is a key similarity: under both regimes, those who don’t hold the default preference will have to register in order to opt out. Let’s suppose, for the sake of argument, that both explicit consent and presumed consent could be implemented with “one-click” technology. Specifically, imagine that the state could successfully contact every citizen (and the parents of minors) by email, asking them to register.

…

Surprisingly, almost as many people (79 percent) agreed to be donors in the neutral condition. Although nearly all states in the United States use a version of explicit consent, many countries in Europe have adopted presumed consent laws (though the cost of opting out varies, and always involves more than a click). Johnson and Goldstein have analyzed the effects of such laws by comparing countries with presumed consent to those with explicit consent. The effect on consent rates is enormous. To get a sense of the power of the default rule, consider the difference in consent rates between two similar countries, Austria and Germany.

The Elements of Choice: Why the Way We Decide Matters

by

Eric J. Johnson

Published 12 Oct 2021

Johnson and Goldstein, “Do Defaults Save Lives?” 2. Thaler and Sunstein, Nudge. 3. Abadie and Gay, “The Impact of Presumed Consent Legislation on Cadaveric Organ Donation: A Cross-Country Study.” 4. Abadie and Gay’s study uses a more sophisticated technique and a larger set of countries than in the original Johnson and Goldstein paper. A systematic review was done in Britain just before the British considered changing the policy: see Rithalia et al., “Impact of Presumed Consent for Organ Donation on Donation Rates: A Systematic Review.” This report looked at studies that compared countries and those that changed and concluded that defaults increased donations in cases.

…

Bilgel, “The Impact of Presumed Consent Laws and Institutions on Deceased Organ Donation,” argues that the effects of defaults depend upon these other factors. A challenge in this entire literature is that it’s impossible to randomly assign countries to a default. But some advanced econometric techniques try to infer causality using instrumental variable regression and argue that the effect of defaults actually causes the increase in transplants, but this is weaker evidence than a causal demonstration. 5. Steffel, Williams, and Tannenbaum, “Does Changing Defaults Save Lives? Effects of Presumed Consent Organ Donation Policies.” 6.

…

The original Singapore law applied only to kidneys available after accidental deaths for non-Muslims. For example, the number of kidney transplants rose from about five per year before the original 1987 law to over forty-nine after the 2004 revision: see Low et al., “Impact of New Legislation on Presumed Consent on Organ Donation on Liver Transplant in Singapore: A Preliminary Analysis.” The Chilean experience is documented in Zúñiga-Fajuri, “Increasing Organ Donation by Presumed Consent and Allocation Priority: Chile.” The Welsh experience followed a long study by the United Kingdom; see “Wales’ Organ Donation Opt-Out Law Has Not Increased Donors.” The French set up a National Rejection Registry; see Eleftheriou-Smith, “All French Citizens Are Now Organ Donors Unless They Opt Out.”

Misbehaving: The Making of Behavioral Economics

by

Richard H. Thaler

Published 10 May 2015

However, some countries in Europe, such as Spain, have adopted an opt-out strategy that is called “presumed consent.” You are presumed to give your permission to have your organs harvested unless you explicitly take the option to opt out and put your name on a list of “non-donors.” The findings of Johnson and Goldstein’s paper showed how powerful default options can be. In countries where the default is to be a donor, almost no one opts out, but in countries with an opt-in policy, often less than half of the population opts in! Here, we thought, was a simple policy prescription: switch to presumed consent. But then we dug deeper. It turns out that most countries with presumed consent do not implement the policy strictly.

…

What is worse is that family members in countries with this regime may have no idea what the donor’s wishes were, since most people simply do nothing. That someone failed to fill out a form opting out of being a donor is not a strong indication of his actual beliefs. We came to the conclusion that presumed consent was not, in fact, the best policy. Instead we liked a variant that had recently been adopted by the state of Illinois and is also used in other U.S. states. When people renew their driver’s license, they are asked whether they wish to be an organ donor. Simply asking people and immediately recording their choices makes it easy to sign up.† In Alaska and Montana, this approach has achieved donation rates exceeding 80%.

…

Econs, see also Econs hyperbolic discounting, see present bias (hyperbolic discounting) hypothetical questions, 38–39, 82 Ibrahim (game show contestant), 304–5 ice companies, 210 ideas42, 184, 344, 345 identified lives, 13 Illinois, 328 impartial spectator, 88, 103 incentive compatible situations, 60 incentives, 47–49, 50, 52 monetary, 353 incentives critique of behavioral economics, 47–49, 50, 52 India, 364 individual investment behavior, 184 Individual Retirement Accounts (IRAs), 310–11, 370 induced value methodology, 40–41, 149–53, 151 inertia, in savings plan, 313 inflation, “real” wages reduced by, 131–32 Influence (Cialdini), 335, 336 Innovations for Poverty Action, 342 inside view, 191 outside view vs., 186–87 instant endowment effect, 154 Intelligent Investor, The (Graham), 219, 220 interest rates, 77–78, 79, 350 intertemporal choice, 88–99 Into Thin Air (Krakauer), 356–57 intrauterine device (IUD), 342 “Invest Now, Drink Later, Spend Never” (Shafir and Thaler), 71 invisible hand, 52, 87 invisible handwave critique of behavioral economics, 51–53, 149, 209 iPhone, 280, 326 Iran, 130 Irrational Exuberance (Shiller), 234 irrelevance theorem and behavioral economics, 164–67 IRS, 314–15 iTunes, 135–36 Ivester, Douglas, 134–35 Iwry, Mark, 314–15, 316 Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL), 344 JC Penney, 62–63 Jensen, Michael, 51–52, 53, 105 and efficient market hypothesis, 205, 207, 208 Jevons, William Stanley, 88, 90 Joey (doll), 129 Johnson, Eric, xv, 82, 180n, 299, 300 on default organ donations, 327–28 Johnson, Ron, 62 Johnson, Steven, 39–40 Jolls, Christine, 184, 257, 258, 260, 269 Jordan, Michael, 19 Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 53–54 Journal of Economic Perspectives, 170–75 Journal of Finance, 243 Journal of Financial Economics, 208 judgment, 179n–80n “Judgment Under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases” (Kahneman and Tversky), 22–23, 24 just noticeable difference (JND), 32–33 Kahneman, Daniel, 21, 22–23, 24, 29, 36, 103n, 104, 125, 126, 140, 148, 157, 162, 176, 221, 335, 338, 353, 357 and “as if” critique of behavioral economics, 46 in behavioral economics debate, 159, 160 in Behavioral Economics Roundtable, 181, 183, 185 book edited by, 187 on changes in wealth, 30–31 endowment effect studied by, 149–55 equity premium puzzle studied by, 197–98 on extreme forecasts with flimsy data, 218, 219, 223 framing studied by, 18 hypothetical choices defended by, 38, 82 lack of incentives in experiments of, 47–48 and “learning” critique of behavioral economics, 49 on long-shot odds, 80–81 narrow framing work of, 186–87, 191 Sunstein’s collaboration with, 258 Thaler’s first meeting with, 36–37 Thaler’s laziness praised by, xv–xvi on theory-induced blindness, 93 and Tversky’s cancer, xiii–xiv two-system view of mind, 103, 109 and Ultimatum Game, 140, 141, 267 unambiguous questions studied by, 295–96 Wanner given advice by, 177 Kan, Raymond, 243 Karlan, Dean, 19 Kashyap, Anil, 272, 273 Katrina, Hurricane, 133, 327 Keynes, John Maynard, 94–95, 96 beauty contest analogy of, 210–11, 212, 214 and behavioral macroeconomics, 349 on conventional wisdom, 210, 292 decline of interest in ideas of, 209 as forerunner of behavioral finance, 209 as investor, 209, 219 on market anomalies, 209–10, 219 kidneys, auctions for, 130 Kitchen Safe, 107n Kleidon, Allan, 167–68, 232 KLM, 356 “Knee-Deep in the Big Muddy” (Staw), 65 Knetsch, Jack, 126, 127–28, 140, 148–49, 267 Kohl’s, 62 Kokonas, Nick, 138–39 Korobkin, Russell, 269 Krakauer, Jon, 356–57 Krueger, Alan B., 139n, 359, 372 Kuhn, Thomas, 167–68, 169, 171, 172, 349 Kunreuther, Howard, 25 Laboratory Experimentation in Economics: Six Points of View (Roth), 148 Labor Department, U.S., 316 Laibson, David, 110, 183, 315n, 353 Lamont, Owen, 244, 250 law and economics, 257–69 law of large numbers, 194–95 law of one price, 237–39, 244, 247, 248, 250, 348 learning critique of behavioral economics, 49–51, 153 Leclerc, France, 257 Lee, Charles, 239 closed-end fund paper of, 240–43, 244 Leno, Jay, 134 Lester, Richard, 44–45 Letwin, Oliver, 331 Levitt, Steven, 354 Lewin, Kurt, 338, 340 liar loans, 252 Liberal Democrats, U.K., 332 libertarian paternalism, 322, 323–25 “Libertarian Paternalism Is Not an Oxymoron” (Sunstein and Thaler), 323–25 Lichtenstein, Sarah, 36, 48 life, value of, see value of a life life-cycle hypothesis, 95–96, 97, 98, 106, 164 “Life You Save May Be Your Own, The” (Schelling), 12–13, 14 limits of arbitrage, 249, 288, 349 Lintner, John, 166, 226, 229 Liquid Assets (Ashenfelter), 68 List, The, 10, 20–21, 24, 25, 31, 33, 36, 39, 43, 58, 68, 303, 347 List, John, 354 lives, statistical vs. identified, 13 loans, for automobiles, 121–23 Loewenstein, George, 88, 111, 176, 180–81, 362 in Behavioral Economics Roundtable, 181 effort project of, 199–201 paternalism and, 323 London, 248 Long Term Capital Management (LTCM), 249, 251 loss aversion, 33–34, 52, 58–59, 154, 261 dividends and, 166 of managers, 187–89, 190 myopic, 195, 198 Lott, John, 265–66 Lovallo, Dan, 186, 187 Lowenstein, Roger, xv–xvi, 12 LSV Asset Management, 228 Lucas, Robert, 159 Luck, Andrew, 289 MacArthur Foundation, 184 Machiguenga people, 364 Machlup, Fritz, 45 macroeconomics: behavioral, 349–52 rational expectations in, 209 Macy’s, 62, 63 Madrian, Brigitte, 315–17 Magliozzi, Ray, 32 Magliozzi, Tom, 32–33 Major League Baseball, 282 “make it easy” mantra, 337–38, 339–40 Malkiel, Burton, 242 managers: growth, 214–15 gut instinct and, 293 loss aversion of, 187–89, 190 risk aversion of, 190–91 value, 214–15 mandated choice, 328–29 marginal, definition of, 27 marginal analysis, 44 marginal propensity to consume (MPC), 94–95, 98 markets, in equilibrium, 44, 131, 150, 207 Markowitz, Harry, 208 marshmallow experiment, 100–101, 102n, 178, 314 Marwell, Gerald, 145 Mas, Alexandre, 372 Massey, Cade, 194, 278–79, 282, 289 Matthew effect, 296n McCoy, Mike, 281–82 McDonald’s, 312 McIntosh, Donald, 103 mean reversion, 222–23 Mechanical Turk (Amazon), 127 Meckling, William, 41, 105 Mehra, Raj, 191 mental accounting, 54, 55, 98, 115, 116, 118, 257 bargains and rip-offs, 57–63 budgeting, 74–79 and equity premium puzzle, 198 on game show, 296–301, 297 getting behind in, 80–84 house money effect, 81–82, 83–84, 193n of savings, 310 sunk costs, 21, 52, 64–73 “two-pocket,” 81–82 Merton, Robert K., 296n “Methodology of Positive Economics, The” (Friedman), 45–46 Mian, Atif, 78 Miljoenenjacht, see Deal or No Deal Miller, Merton, 159, 167–68, 206, 208 annoyed at closed-end fund paper, 242–43, 244, 259 irrelevance theorem of, 164–65, 166–67 Nobel Prize won by, 164 Thaler’s appointment at University of Chicago, reaction to, 255, 256 Minnesota, 335 Mischel, Walter, 100–101, 102, 103, 178, 314 mispricing, 225 models: beta–delta, 110 of homo economicus, 4–5, 6–7, 8–9, 23–24, 180 imprecision of, 23–24 optimization-based, 5–6, 8, 27, 43, 207 Modigliani, Franco: consumption function of, 94, 95–96, 97, 98, 309 irrelevance theorem of, 164–65 Nobel Prize won by, 163–64 Moore, Michael, 122 More Guns, Less Crime (Lott), 265 Morgenstern, Oskar, 29 mortgage brokers, 77–78 mortgages, 7, 77–79, 252, 345 mugs, 153, 155, 263, 264–66, 264 Mullainathan, Sendhil, 58n, 183–84, 366 Mulligan, Casey, 321–22 Murray, Bill, 49–50 mutual fund portfolios, 84 mutual funds, 242 myopic loss aversion, 195, 198 Nagel, Rosemarie, 212 naïve agents, 110–11 Nalebuff, Barry, 170 narrow framing, 185–91 and effort project, 201 NASDAQ, 250, 252 Nash, John, 212 Nash equilibrium, 212, 213n, 367 National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), 35, 236, 244, 349 National Football League, 139n draft in, 11, 277–91, 281, 283, 285, 286 rookie salaries in, 283 salary cap in, 282–83 surplus value of players in, 285–86, 285, 286, 288 National Public Radio, 32, 305 naturally occurring experiments, 8 NESTA, 343 Net Asset Value (NAV) fund, 238–39, 241 Netherlands, 248, 296–301 neuro-economics, 177, 182 New Contrarian Investment Strategy, The (Dreman), 221–22 New Orleans Saints, 279 New York, 137 New Yorker, 90–91, 91, 92 New York Stock Exchange, 223, 226, 232, 248 New York Times, 292, 327, 328 New York Times Magazine, xv–xvi, 12 Next Restaurant, 138–39 NFL draft, 11, 277–91, 281, 283, 285, 286, 295 Nick (game show contestant), 304–5 Nielsen SoundScan, 135 Nixon, Richard, 363 Nobel, Alfred, 23n Nobel Prize, 23, 40, 207 no free lunch principle, 206, 207, 222, 225, 226n, 227, 230, 233–36, 234, 236, 251, 255 noise traders, 240–42, 247, 251 nomenclature, importance of, 328–29 Norman, Don, 326 normative theories, 25–27 “Note on the Measurement of Utility, A” (Samuelson), 89–94 no trade theorem, 217 Nudge (Thaler and Sunstein), 325–26, 330, 331–32, 333, 335, 345 nudges, nudging, 325–29, 359 number game, 211–14, 213 Obama, Barack, 22 occupations, dangerous, 14–15 Odean, Terry, 184 O’Donnell, Gus, 332–33 O’Donoghue, Ted, 110, 323 Odysseus, 99–100, 101 Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA), 343–44 Office of Management and Budget, 343 offices, 270–76, 278 “one-click” interventions, 341–42 open-end funds, 238 opportunity costs, 17, 18, 57–58, 59, 73 of poor people, 58n optimal paternalism, 323 optimization, 5–6, 8, 27, 43, 161, 207, 365 Oreo experiment, 100–101, 102n, 178, 314 organizations, theory of, 105, 109 organs: donations of, 327–28 markets for, 130 Osborne, George, 331 Oullier, Olivier, 333 outside view, inside view vs., 186–87 overconfidence, 6, 52, 124, 355 and high trading volume in finance markets, 217–18 in NFL draft, 280, 295 overreaction: in financial markets, 219–20, 222–24, 225–29 generalized, 223–24 to sense of humor, 218, 219, 223 value stocks and, 225–29 Oxford Handbook of Behavioral Economics and the Law, 269 Palm and 3Com, 244–49, 246, 250, 348 paradigms, 167–68, 169–70 Pareto, Vilfredo, 93 parking tickets, 260 passions, 7, 88, 103 paternalism, 269, 322 dislike of term, 324 libertarian, 322, 323–25 path dependence, 298–300 “pay as you earn” system, 335 payment depreciation, 67 Pearl Harbor, Japanese bombing of, 232 P/E effect, 219–20, 222–23, 233, 235 pensions, 9, 198, 241, 320, 357–58 permanent income hypothesis, 95 Peter Principle, 293 pharmaceutical companies, 189–90 Pigou, Arthur, 88, 90 plane tickets, 138 planner-doer model, 104–10 Plott, Charlie, 40, 41, 48, 49, 148, 149, 177, 181 poker, 80, 81–82, 99 poor, 58n Posner, Richard, 259–61, 266 Post, Thierry, 296 poverty, decision making and, 371 Power, Samantha, 330 “Power of Suggestion, The” (Madrian and Shea), 315 practice, 50 predictable errors, 23–24 preferences: change in, 102–3 revealed, 86 well-defined, 48–49 pregnancy, teenage, 342 Prelec, Drazen, 179 Prescott, Edward, 191, 192 present bias (hyperbolic discounting), 91–92, 110, 227n and NFL draft, 280, 287 savings and, 314 presumed consent, in organ donations, 328–29 price controls, 363 price/earnings ratio (P/E), 219–20, 222–23, 233, 235 prices: buying vs. selling, 17, 18–19, 20, 21 rationality of, 206, 222, 230–33, 231, 237, 251–52 variability of stock, 230–33, 231, 367 price-to-rental ratios, 252 principal-agent model, 105–9, 291 Prisoner’s Dilemma, 143–44, 145, 301–5, 302 “Problem of Social Cost, The” (Coase), 263–64 profit maximization, 27, 30 promotional pricing strategy, 62n prompted choice (in organ donation), 327–29 prospect theory, 25–28, 295, 353 acceptance of, 38–39 and “as if” critique of behavioral economics, 46 and consumer choice, 55 and equity premium puzzle, 198 expected utility theory vs., 29 surveys used in experiments of, 38 psychological accounting, see mental accounting “Psychology and Economics Conference Handbook,” 163 “Psychology and Savings Policies” (Thaler), 310–13 Ptolemaic astronomy, 169–70 public goods, 144–45 Public Goods Game, 144–46 Punishment Game, 141–43, 146 Pythagorean theorem, 25–27 qualified default investment alternatives, 316 quantitative analysis, 293 Quarterly Journal of Economics, 197, 201 quasi-hyperbolic discounting, 91–92 quilt, 57, 59, 61, 65 Rabin, Matthew, 110, 181–83, 353 paternalism and, 323 racetracks, 80–81, 174–75 Radiolab, 305 randomized control trials (RCTs), 8, 338–43, 344, 371 in education, 353–54 Random Walk Down Walk Street, A (Malkiel), 242 rational expectations, 98, 191 in macroeconomics, 209 rational forecasts, 230–31 rationality: bounded, 23–24, 29, 162 Chicago debate on, 159–63, 167–68, 169, 170, 205 READY4K!

SuperFreakonomics

by

Steven D. Levitt

and

Stephen J. Dubner

Published 19 Oct 2009

ORGAN TRANSPLANTS: The first successful long-term kidney transplant was performed at the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital in Boston by Joseph Murray in December 1954, as related in Nicholas Tilney, Transplant: From Myth to Reality (Yale University Press, 2003). / 111 “Donorcyclists”: see Stacy Dickert-Conlin, Todd Elder, and Brian Moore, “Donorcycles: Do Motorcycle Helmet Laws Reduce Organ Donations?” Michigan State University working paper, 2009. / 111 “Presumed consent” laws in Europe: see Alberto Abadie and Sebastien Gay, “The Impact of Presumed Consent Legislation on Cadaveric Organ Donation: A Cross Country Study,” Journal of Health Economics 25, no. 4 (July 2006). / 112 The Iranian kidney program is described in Ahad J. Ghods and Shekoufeh Savaj, “Iranian Model of Paid and Regulated Living-Unrelated Kidney Donation,” Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 1 (October 2006); and Benjamin E.

…

In the United States, the rate of traffic fatalities was declining, which was great news for drivers but bad news for patients awaiting a lifesaving kidney. (At least motorcycle deaths kept up, thanks in part to many state laws allowing motorcyclists—or, as transplant surgeons call them, “donorcyclists”—to ride without helmets.) In Europe, some countries passed laws of “presumed consent” rather than requesting that a person donate his organs in the event of an accident, the state assumed the right to harvest his organs unless he or his family specifically opted out. But even so, there were never enough kidneys to go around. Fortunately, cadavers aren’t the only source of organs.

Naked Economics: Undressing the Dismal Science (Fully Revised and Updated)

by

Charles Wheelan

Published 18 Apr 2010

This idea has profound implications when it comes to something like organ donation. Spain, France, Norway, Israel, and many other countries have “opt-out” (or presumed consent) laws when it comes to organ donation. You are an organ donor unless you indicate otherwise, which you are free to do. (In contrast, the United States has an “opt-in” system, meaning that you are not an organ donor unless you sign up to be one.) Inertia matters, even when it comes to something as serious as organ donation. Economists have found that presumed consent laws have a significant positive effect on organ donation, controlling for relevant country characteristics such as religion and health expenditures.

…

Economists have found that presumed consent laws have a significant positive effect on organ donation, controlling for relevant country characteristics such as religion and health expenditures. Spain has the highest rate of cadaveric organ donations in the world—50 percent higher than the United States.14 True libertarians (as opposed to the paternalistic kind) reject presumed consent laws, because they imply that the government “owns” your internal organs until you make some effort to get them back. Good government matters. The more sophisticated our economy becomes, the more sophisticated our government institutions need to be. The Internet is a perfect example. The private sector is the engine of growth for the web economy, but it is the government that roots out fraud, makes on-line transactions legally binding, sorts out property rights (such as domain names), settles disputes, and deals with issues that we have not even thought about yet.

…

Barry Bearak, “In India, the Wheels of Justice Hardly Move,” New York Times, June 1, 2000. 12. Thomas L. Friedman, “I Love D.C.,” New York Times, November 7, 2000, p. A29. 13. Amartya Sen, Development as Freedom (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1999). 14. Giacomo Balbinotto Neto, Ana Katarina Campelo, and Everton Nunes da Silva, “The Impact of Presumed Consent Law on Organ Donation: An Empirical Analysis from Quantile Regression for Longitudinal Data,” Berkeley Program in Law & Economics, Paper 050107–2 (2007). CHAPTER 4. GOVERNMENT AND THE ECONOMY II 1. John Markoff, “CIA Tries Foray into Capitalism,” New York Times, September 29, 1999. 2.

Inside the Nudge Unit: How Small Changes Can Make a Big Difference

by

David Halpern

Published 26 Aug 2015

Curiously, one of Prime Minister Brown’s smartest new political aids, Greg Beales, had worked on the original PMSU paper on behaviour change. In the new No. 10, Greg held responsibility for health. It’s no coincidence, then, that one early move of the Brown administration was to float the idea of changing the defaults on organ donation to ‘presumed consent’ – where people would opt out of being donors, rather than opt in. But even this was not quite the right fight for that time or issue. There was a public and professional backlash against the idea, and the last whisper of the old PMSU paper was silenced for now, in Britain at least.19 On the other side of the Atlantic, behavioural approaches to policy were about to get a major boost.

…

We all agreed that an early objective would be to try out some of the most prominent and best-evidenced ideas from the wider literature, and from the US in particular. These could provide some early quick wins, and help to establish the approach. For example, we suspected that a version of a successful ‘promoted choice’ approach to organ donation in Illinois could work well in the UK without needing to go for the ‘presumed consent’ method that had been proposed by the previous Brown government and abandoned in the face of public opposition. If it worked, it would be a nice illustration of the Coalition’s different approach, and of course would hopefully save a few lives. Other criteria for early priorities were that: the issue was a PM or DPM priority; the intervention was likely to be revenue-producing or saving (given the pressures on budgets); and the intervention was amenable to systematic testing and trialling, with good management data in place that we could use for measurement.

…

Both were later merged to form the PM’s Strategy Unit, which lasted until it was shut down by the 2010 Coalition Government of Cameron and Clegg in early 2011. 18 Cialdini, R. B. (2003). ‘Crafting normative messages to protect the environment’. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12(4), 105–109. 19 Interestingly, the Welsh Government did continue to pursue the idea of presumed consent. Organ donation was also on the list of early topics for BIT in 2010, though with a subtly different solution in mind. Chapter 2: Nudging Goes Mainstream 1 In my view Richard Thaler’s work is sufficiently outstanding and impactful in its own right to merit the Nobel Prize in economics, a view I know to be shared by many others.

Think Twice: Harnessing the Power of Counterintuition

by

Michael J. Mauboussin

Published 6 Nov 2012

If you are like most people, you answered yes to the first question. But the response to the second question depends a great deal on which country you live in. For instance, take neighboring countries Germany and Austria. Only 12 percent of Germans have explicitly consented to donate their organs, while virtually 100 percent of Austrians have offered presumed consent. (See figure 4–3.) The difference? In Germany, you must opt in to become a donor. In Austria, you must opt out to avoid being a donor. The consent gap has less to do with attitudes about donating than it does with default options. The difference translates into saved lives; the actual rate of organ donation is notably higher in opt-out countries.16 The donor statistics point to our second mistake: the perception that people decide what is best for them independent of how the choice is framed.

The Knife's Edge

by

Stephen Westaby

Published 14 May 2019

As the efficient young man turned to leave, I said, ‘Please tell Professor Cranston that I don’t want any blood transfusion.’ Then, tempting fate, I added, ‘If I suffer a fatal stroke during surgery I’m happy to be an organ donor.’ Altruistic to the end, but he didn’t hear me so the gesture was wasted. With the introduction of ‘presumed’ consent in contrast to voluntary donation, I’ve since reconsidered that. It’s a throwback to the body-snatching era. I was still reading in my white theatre gown when Oliver Dyar the anaesthetist walked in. I had known Oliver for twenty years or more as one of the intensive care consultants who looked after my patients.

The Precariat: The New Dangerous Class

by

Guy Standing

Published 27 Feb 2011

But there was no opt-out form included, so people wishing to do so had to go to a website, find a form to download, print it, sign it, send it as a letter to their general practitioner (GP) and hope it would be acted upon. Bureaucratic hurdles were deliberately raised, increasing the cost of opting out and giving a bias to ‘presumed consent’. Those least likely to opt out are the uneducated, the poor and the ‘digitally excluded’, mostly elderly without access to online facilities. As of 2010, 63 per cent of all those over the age of 65 in the United Kingdom lived in a household without internet access. There is government pressure, led by its ‘digital inclusion champion’, for more people to have access.

Animal: The Autobiography of a Female Body

by

Sara Pascoe

Published 18 Apr 2016

Sane men do not lose control and begin masturbating in front of everybody at the party; they remain aware of right and wrong, of embarrassment and propriety, even when intoxicated. Respect for women’s bodies, whether they be asleep, or naked or drugged, should be learned like toilet training. It has to be taught. It’s too dangerous to presume consent is obvious and that anyone who gets it wrong is a bad person. This needs deep thought and conversations. And alcohol is a very complicating factor. There is a point of drunkenness where people are considered unable to give consent to various things, including sexual contact. There are multitudes of warnings aimed at young women, shouting about the dangers of being wasted and vulnerable, while there is virtually nothing aimed at educating young men.

Our Posthuman Future: Consequences of the Biotechnology Revolution

by

Francis Fukuyama

Published 1 Jan 2002

thymos (spiritedness) time, concept of Tocqueville, Alexis de totalitarianism, collapse of transgenic crops Tribe, Laurence Trivers, Robert Tsien, Joe Turing test Turkey Tuskegee syphilis scandal twin studies typical, meaning of word tyranny failure of of the majority unborn presumed consent of rights of United Kingdom United Nations United States attitude toward regulation attitude toward technology demographic trends in family breakdown in international influence of, re regulation natural right as foundation of political system, effect on regulation principles of regulatory policy and practice U.S.

Work! Consume! Die!

by

Frankie Boyle

Published 12 Oct 2011

How will they then afford a ticket to my show? The NHS is under pressure to withdraw pornography from patients who need to give sperm samples. I think it’s a terrible idea to remove pornography from hospitals. It’s pretty much the only reason I visited Dad after his bypass operation. Wales is to introduce presumed consent for organ donation. This should greatly improve patient survival rates … as doctors there offer still-beating hearts as gifts to call upon the healing powers of their many gods. And a hospital in Cardiff gave its elderly patients tambourines and maracas to summon medical help. Not sure that’ll work.

Consumed: How Markets Corrupt Children, Infantilize Adults, and Swallow Citizens Whole

by

Benjamin R. Barber

Published 1 Jan 2007

“Under mandated choice, as much as 75% of the U.S. adult population would become committed potential organ donors” (Aron Spital, “Mandated Choice for Organ Donation: Time to Give It a Try,” Annals of Internal Medicine, vol. 125 [ July 1996], pp. 66–69). “We surveyed members of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) in conjunction with the Foundation for the Advancement of Cardiac Therapies FACT). METHODS/RESULTS: We asked for opinions about how to improve organ donation. Of 739 respondents, 75% supported presumed consent” (M. C. Oz et al., “How to improve organ donation: results of the ISHLT/FACT poll,” Heart Lung Transplant, vol. 22, no. 4 [April 2003], pp. 389–410). 47. Rousseau used this phrase in his 1762 Social Contract, and it has led many liberals focused on private liberty alone to conclude that Rousseau was either incoherent or a dangerous protototalitarian thinker of the kind George Orwell would eventually skewer.

Lonely Planet Iceland (Travel Guide)

by

Lonely Planet

,

Carolyn Bain

and

Alexis Averbuck

Published 31 Mar 2015

In 1996, neuroscience expert Dr Kári Stefánsson recognised that this genealogical material could be combined with Iceland’s unusually homogenous population to produce something unique – a country-sized genetic laboratory. In 1998 the Icelandic government controversially voted to allow the creation of a single database, by presumed consent, containing all Icelanders’ genealogical, genetic and medical records. Even more controversially, the government allowed Kári’s biotech startup company deCODE Genetics to create this database, and access it for its biomedical research, using the database to trace inheritable diseases and pinpoint the genes that cause them.

Lonely Planet Iceland

by

Lonely Planet

In 1996, neuroscience expert Dr Kári Stefánsson recognised that this genealogical material could be combined with Iceland’s unusually homogenous population to produce something unique – a country-sized genetic laboratory. In 1998 the Icelandic government controversially voted to allow the creation of a single database, by presumed consent, containing all Icelanders’ genealogical, genetic and medical records. Even more controversially, the government allowed Kári’s biotech startup company Decode Genetics to create this database, and access it for its biomedical research, using the database to trace inheritable diseases and pinpoint the genes that cause them.

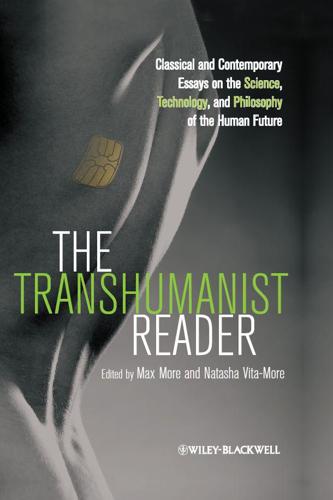

The Transhumanist Reader

by

Max More

and

Natasha Vita-More

Published 4 Mar 2013

But the requirement that all future generations must consent adds nothing to the moral force of Allhoff’s arguments since already all rational agents would consent to such enhancements. So again, safe genetic interventions that improve a prospective child’s health, cognition, and so forth would be morally permissible because we can presume consent from the individuals who benefit from the enhancements. Many opponents of human genetic engineering are either conscious or unconscious genetic determinists. They fear that biotechnological knowledge and practice will somehow undermine human freedom. In a sense, these genetic determinists believe that somehow human freedom resides in the gaps of our knowledge of our genetic makeup.