The Dollar Meltdown: Surviving the Coming Currency Crisis With Gold, Oil, and Other Unconventional Investments

by

Charles Goyette

Published 29 Oct 2009

Consumers quit consuming when they discover that the dollar they don’t spend today buys more tomorrow. The situation is often likened to trying to “push on a string.” The Federal Reserve can monetize debt, purchase government bonds, and make reserves available to the banking system. But it can’t force businesses to borrow. If no one borrows, there is no stimulative effect in the economy. Deflation is a subject of special interest to many economists including Ben Bernanke, the current Federal Reserve chairman, who has written extensively about it. In a widely noted speech in 2002, Bernanke sought to answer the “pushing on a string” case for deflation, saying that the Fed and the government have sufficient means to ensure that any such interlude would be mild and brief.

…

Already the Fed is buying short-term corporate debt in the commercial paper market. It can even buy mortgages. Bernanke discusses several other means of countering deflation and concludes that the monetary and fiscal authorities “would be far from helpless in the face of deflation. . . .” Still this does not quite answer the “pushing on a string” argument of deflationists. What can the Fed do to be sure of generating public spending with its monetary policies? The answer: whatever it takes. The Fed will use any tool at its disposal to stop a threat of deflation. It will create new tools and assume heretofore unseen authority if need be.

…

See Gold coinage; Silver coinage Collectibles, precious metals as Command economy as anti-American bank nationalization currency controls features of financial behavior, reporting and poverty shortages and rationing wage and price controls Commodities as investment exchange-traded funds (ETFs) exchange-traded notes (ETNs) Rogers International Commodity Index (RICI) Consumer Price Index (CPI), core inflation rate as alternative Consumption, decline and deflation Core inflation rate Corzine, Jon Cost-push inflation Counterfeit, gold coins Countrywide Financial “Crack-up boom,” Credit, artificial and malinvestment Credit crisis Credit Suisse Currency controls, and monetary breakdown foreign. See Foreign currency as investment hard currencies DB Commodity Services LLC, Debt, federal. See Federal debt Debt securities exchange-traded notes (ETNs) U.S. government. See Treasury bonds Deflation bailout, effects on economic impact of myths about “pushing on a string” argument De Gaulle, Charles Deng Xiaoping Digital gold currencies GoldMoney Dollar as currency reserves deterioration, and oil-pricing alternatives devaluation and Fed overseas holdings Dollar standard benefits to U.S. global dumping of Economic collapse, signs of Economic crisis (2008- ) bailouts command economy threat credit crisis and dollar standard federal debt government actions.

Samuelson Friedman: The Battle Over the Free Market

by

Nicholas Wapshott

Published 2 Aug 2021

“I’d always assumed that if deflation seemed imminent, we could start up the printing presses and create as many dollars as would be necessary to stop a deflationary spiral,” recalled Greenspan. “Now I was not sure.”19 Flooding the system with cheap money was one of the few instruments left to Greenspan, though the Fed chair knew the truth of Keynes’s economic adage, “You cannot push on a string”20—in other words, you can offer cheap money to banks and entrepreneurs, but, if investors see no opportunities and therefore do not wish to borrow, or banks are reluctant to lend, there is nothing a government can do to force them. Acutely aware that by cutting interest rates further he risked “a bubble, an inflationary boom of some sort,” which would have to be addressed at some time, in June 2003 Greenspan cut rates again, to 1 percent.

…

“Once the nominal interest rate is at zero,” he explained, “no further downward adjustment in the rate can occur, since lenders generally will not accept a negative nominal interest rate when it is possible instead to hold cash.” When the short-term interest rate reached zero, it had been suggested that central banks would “run out of ammunition” and would be powerless to affect events through manipulating interest rates. However, Bernanke argued that, notwithstanding Keynes’s notion that “you cannot push on a string,” a central bank still retained “considerable power to expand aggregate demand3 and economic activity even when its accustomed policy rate is at zero.” This included the wholesale printing of money through credit swaps—the Fed buying back its own debt and relending at a lower rate—a policy that would become known as “quantitative easing.”

…

And when this proved inadequate, in December 2008 the Fed reduced interest rates to zero and let it be known there was little prospect of raising them again for a very long time. The Federal Reserve became the lender of last resort to banks and financial institutions it deemed creditworthy, stepping in to guarantee short-term loans between banks that otherwise may have been considered too risky. It was not enough. The truth of Keynes’s adage “You cannot push on a string” soon became evident. It proved easier to make limitless amounts of cash cheaply available than it was to find good uses for it. As Bernanke explained, “Conventional monetary policy alone is not adequate to provide all the support that the economy needs.”15 In its dying days, the Bush administration prepared the Economic Stimulus Act of 2008 that would, when passed by Congress in the early weeks of Barack Obama’s presidency, provide nearly a trillion dollars to stimulate the economy directly through government spending on infrastructure, tax breaks, and other Keynesian antirecession devices.

Big Debt Crises

by

Ray Dalio

Published 9 Sep 2018

Ugly inflationary depressions arise in cases where policy makers allow faith in the currency to collapse and print too much money. 6) “Pushing on a String” Late in the long-term debt cycle, central bankers sometimes struggle to convert their stimulative policies into increased spending because the effects of lowering interest rates and central banks’ purchases of debt assets have diminished. At such times the economy enters a period of low growth and low returns on assets, and central bankers have to move to other forms of monetary stimulation in which money and credit go more directly to support spenders. When policy makers faced these conditions in the 1930s, they coined the phrase “pushing on a string.” One of the biggest risks at this stage is that if there is too much printing of money/monetization and too severe a currency devaluation relative to the amounts of the deflationary alternatives, an “ugly inflationary deleveraging” can occur.

…

A Template for Understanding BIG DEBT CRISES Ray Dalio Table of Contents A Template for Understanding Big Debt Crises Acknowledgements Introduction PART 1: The Archetypal Big Debt Cycle How I Think about Credit and Debt The Template for the Archetypal Long-Term/Big Debt Cycle Our Examination of the Cycle The Phases of the Classic Deflationary Debt Cycle The Early Part of the Cycle The Bubble The Top The “Depression” The “Beautiful Deleveraging” “Pushing on a String” Normalization Inflationary Depressions and Currency Crises The Phases of the Classic Inflationary Debt Cycle The Early Part of the Cycle The Bubble The Top and Currency Defense The Depression (Often When the Currency Is Let Go) Normalization The Spiral from a More Transitory Inflationary Depression to Hyperinflation War Economies In Summary PART 2: Detailed Case Studies German Debt Crisis and Hyperinflation (1918-1924) US Debt Crisis and Adjustment (1928–1937) US Debt Crisis and Adjustment (2007–2011) PART 3: Compendium of 48 Case Studies Glossary of Key Economic Terms Primarily Domestic Currency Debt Crises Non-Domestic Currency Debt Crises Appendix: Macroprudential Policies Acknowledgements I cannot adequately thank the many people at Bridgewater who have shared, and continue to share, my mission to understand the markets and to test that understanding in the real world.

…

PART 1: The Archetypal Big Debt Cycle How I Think about Credit and Debt The Template for the Archetypal Long-Term/Big Debt Cycle Our Examination of the Cycle The Phases of the Classic Deflationary Debt Cycle The Early Part of the Cycle • The Bubble • The Top • The “Depression” • The “Beautiful Deleveraging” • “Pushing on a String” • Normalization Inflationary Depressions and Currency Crises The Phases of the Classic Inflationary Debt Cycle The Early Part of the Cycle • The Bubble • The Top and Currency Defense • The Depression (Often When the Currency Is Let Go) • Normalization The Spiral from a More Transitory Inflationary Depression to Hyperinflation War Economies In Summary How I Think about Credit and Debt Since we are going to use the terms “credit” and “debt” a lot, I’d like to start with what they are and how they work.

Fed Up: An Insider's Take on Why the Federal Reserve Is Bad for America

by

Danielle Dimartino Booth

Published 14 Feb 2017

“Too many dissents, I worried, could undermine our credibility.” But tradition be damned, Fisher refused to be a yes man. He always feared the consequences of “pushing on a string”—a phrase with a venerable history at the Fed. In 1935, Federal Reserve Chairman Marriner Eccles testified during hearings on the Banking Act that little could be done with monetary policy to stimulate growth. “You mean you cannot push on a string?” Congressman Alan Goldsborough said. “That is a very good way to put it, one cannot push on a string,” Eccles said. “We are in the depths of a depression and . . . beyond creating an easy money situation through reduction of discount rates . . . there is very little, if anything, that the [federal] reserve organization can do toward bringing about recovery.”

…

“I find myself conciliating”: Bernanke, The Courage to Act, 238. Kohn responded to Bernanke’s e-mail by pointing out that “after a honeymoon period of three meetings without dissent in 1987, the Maestro had faced dissents in nineteen of his next twenty-one meetings.” The Fed’s tradition of: Ibid. “You mean you cannot push on a string?”: John H. Wood, A History of Central Banking in Great Britain and the United States (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 231. “It’s really a question”: Sudeep Reddy, “Fisher: Fix the Credit System First,” Wall Street Journal, April 22, 2008. In mid-April 2008: Maurna Desmond, “IMF: Subprime Losses Could Hit $1 Trillion,” Forbes.com, April 8, 2008, www.forbes.com/2008/03/31/subprime-costs-writedowns-markets-equity-cx_md-0331markets21.html.

The Upside of Inequality

by

Edward Conard

Published 1 Sep 2016

Paul Krugman, “The Conscience of a Liberal: Monetary Policy in a Liquidity Trap,” New York Times, April 11, 2013, http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/04/11/monetary-policy-in-a-liquidity-trap. 54. Martin Wolf, “Lunch with the FT: Ben Bernanke,” Financial Times, October 23, 2015, http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/0c07ba88-7822-11e5-a95a-27d368e1ddf7.html. 55. “Pushing on a String,” Wikipedia, accessed December 18, 2015, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pushing_on_a_string. 56. Paul Krugman, “The Conscience of a Liberal: Rethinking Japan,” New York Times, October 20, 2015, http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/10/20/rethinking-japan. 57. John Cochrane, “The Fed Needn’t Rush to ‘Normalize,’” Wall Street Journal, September 16, 2015, http://www.wsj.com/articles/the-fed-neednt-rush-to-normalize-1442441737.

…

One explanation could be that the Fed can’t conduct monetary policy in a way that threatens price inflation, even if it wanted to. Borrowing and spending entail risk—by both lenders and borrowers. When the economy’s capacity and willingness to bear risk binds growth, savings and money sit unused. Increasing the monetary base just pushes on a string.55 Idle savings, the Fed’s inability to produce inflation, and the zero lower bound are all symptoms of the economy’s capacity and willingness to bear risk, binding growth. Krugman agrees that printing money, on its own, won’t create inflation. He insists that to produce inflation, the government must increase spending to tighten capacity utilization56 . . . assuming no corresponding private-sector dial-back, of course!

The End of Indexing: Six Structural Mega-Trends That Threaten Passive Investing

by

Niels Jensen

Published 25 Mar 2018

The nature of debt super-cycles In a debt super-cycle, as the cycle advances, economic growth is increasingly driven by a combination of growth in debt and money supply. Having said that, there are obviously limits as to how much spending can be financed by debt and money. When that point is reached, you are at the end of the debt super-cycle. John Maynard Keynes called it Push on a String, when he first described the phenomenon in 1935. Nowadays, it is often called the Liquidity Trap. When debt rises fast – and fast in this context means faster than GDP growth – capital that could otherwise be used productively to enhance GDP growth is instead used to service existing debt, i.e. it is used unproductively.

…

Debt rising faster than GDP is a vicious circle. As GDP growth slows, more debt is needed to service existing debt, which will cause GDP growth to slow even further. Debt therefore continues to grow, and GDP growth continues to slow, until it all ends in tears. What we are now beginning to see are the first signs of Push on a String. When that happens, monetary policy is already so accommodative that further rate cuts have virtually no effect on economic growth. QE also becomes largely ineffective, as risk premia are too low to drive investors to assume more risk. The very low returns that we currently see across almost all asset classes is a classic sign that we are approaching the end of the debt super-cycle.

Big Three in Economics: Adam Smith, Karl Marx, and John Maynard Keynes

by

Mark Skousen

Published 22 Dec 2006

Even Yale's James Tobin, a friendly critic, recognized its greatness: "This is one of those rare books that leaves their mark on all future research on the subject" (1965, 485). Friedman had a twofold mission in researching and writing Monetary History. First, he wanted to dispel the prevailing Keynesian notion that "money doesn't matter," that somehow an aggressive expansion of the money supply during a recession or depression cannot be effective, like "pushing on a string." Friedman and Schwartz showed time and time again that monetary policy was indeed effective in both expansions and contractions. Friedman's work on monetary economics became increasingly important and applicable as inflation headed upward in the 1960s and 1970s. His most famous line is "Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon" (Friedman 1968, 105).

…

For thirty years, an entire generation of economists did not really know the extent of the damage the Federal Reserve had inflicted on the U.S. economy from 1929 to 1933. They had been under the impression that the Fed had done everything humanly possible to keep the depression from worsening, but like "pushing on a string," were impotent in the face of overwhelming deflationary forces. According to the official apologia of the Federal Reserve System, it had done its best, but was powerless to stop the collapse. Friedman radically altered this conventional view. "The Great Contraction," as Friedman and Schwartz called it, "is in fact a tragic testimonial to the importance of monetary forces" (Friedman and Schwartz 1963, 300).

Inflated: How Money and Debt Built the American Dream

by

R. Christopher Whalen

Published 7 Dec 2010

Meltzer added in the same portion of his landmark book that Eccles was not an apologist for deficits generally, but only to offset deficits in investment spending. He observes that despite the prominence of Keynes’s work at the time, Eccles claimed never to have read his books nor to have derived any of his own views on deficit spending from Keynes main work.61 Meltzer documents how Eccles came to be associated with the term “pushing on a string” in 1935 during testimony before the House Committee on Banking and Currency. He knew that monetary expansion did not work in the Depression because people were unwilling to spend or borrow. But Eccles went further than many of his contemporaries and attributed the excess of savings to inequitable income distribution.

…

(Barron ownership) Dow Jones Industrial Average, decline (1929) Drew, Daniel Drysdale Government Securities, collapse Dunbar, Willis Dunkelberg, William Dunn, Susan du Pont, Pierre S. Durant, William Durant‘s Folly Earning power, assets (relationship, absence) Ebeling, Richard Eccles, Marriner Glass, opposition pushing on a string Truman anger Economic depression (1882-1884) Economic expansion, Burns limitation Economic growth, generation Economic output, WWI decline Economic Recovery Tax Act (1981) Economic Stabilization Act Economic stagnation, Nixon response Economy, American uncertainty/doubt Economy (angst), American political class (response) Einhorn, David Einstein, Albert Eisenhower, Dwight David defense industrial complex warning election Electrification, impact Embargos, removal (FDR support) Emergency Banking Act (1933) Emergency Banking Relief Act Employment Act (1946) passage Employment maximum, promotion Energy costs, impact Equity markets, decline Erie Railroad collapse control, theft Eurodollars deposits, dollar supply (visibility) Europe American imports, decline collapse credit, U.S. dependence deflation goods flow, American dependence unemployment (1873) WWI debt payment, failure/refusal WWII loans WWI loans European imports, WWI financing requirement European nations, U.S. trade deficit European style corporate statism, American version (FDR endorsement) European Union crisis (2010) emergence success Exchange medium Exchange Stabilization Fund (ESF) (1933) Executive Branch, power (growth) External deficits, increase (impact) Faris, Ralph Farley, James Farm cooperatives, formation Farm Credit Banks, usage Farmer’s Exchange Bank, failure Farm prices/wages, decline (continuation) Farm sector, commodity prices (collapse) Faulkner, Harold Federal debt (1945-1996) level (1974) shrinkage U.S. government servicing Federal deposit insurance, FDR support Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) idea, proposal panic role permanency Federal expenditures, Hoover avoidance Federal funds rate, increase Federal government greenback issuance, legality (debate) laissez faire role, return post-Civil War debt size (increase), FDR (impact) Federal Home Loan Bank Board, authorization Federal Home Loan Banks (FHLBs) authorization Hoover creation Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (FHLMC) Federal insurance, access Federal Land Bank Federal Monetary Authority Federal National Mortgage Association (FNMA) creation Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) capitulation federal funds rate, increase interest rate control Federal outlays (1968-1976) Federal outlays (1979-1988) Federal receipts (1929-1996) Federal Reserve Act (1913) amendment, banking lobby (impact) approval Bryan support compromise decentralized features evolution impact passage Byrd perspective political equation, shift Federal Reserve banks, National Monetary Commission organization Federal Reserve Money Federal Reserve System Board of Governors creation, McFadden Act (impact) original composition corportivist reform creation impact Jefferson/Jackson, cautionary views (confirmation) deflationary tone Durant complaints evolution Galbraith description High Tide imperfections independence, retention liquidity provider motivation (2000s) policies, questions rediscounting regulation changes, Warburg opposition RFC, relationship tunnel-vision policies, adoption warrants, purchase (Federal Reserve Act limitation) WWI actions Federal revenues, growth Federal spending, increase Federal Trade Act Fed of New York, discount rate (reduction) Feinberg, Robert Fessenden, William P.

…

Novak, Robert O’Driscoll, Gerald Offshore market, dollar deposits Oil companies, asset choice Oil industry, deregulation Oil prices, shocks Oklahoma bank, FDIC assistance Open market operations control, centralization Orwell, George (1984) Outstanding consumer debt, increase Owen, Robert proposal Paine, Thomas Panic of 1873 Panic of 1893 Panic of 1897 Panic of 1901 Panic of 1907 social/economic effects Paper currency emission, Lincoln precedent legal tender acceptance manufacture, establishment value, speculation (tactics) Paper dollars, gold (relationship) Paper money American opposition market dynamic post-Civil War supply contraction, assumption preference supply, increase suspicion Paper notes, interest-free debt Past earnings, significance Patton, George Eisenhower opposition Paul, Ron Peace insurance Pearl Harbor, Japan attack Pecora, Ferdinand Pemex, oil monopoly Penn Central, bailout Penn Square Bank, collapse inevitability Pennsyvania Steel Trust, control Peter the Hermit (Crusades) Philippines, acquisition (Hobart involvement) Phillips, Kevin Ping, Luo Platt, Orville Platt, Tom business interests Plaza Accord Pollock, Alex Pomerene, Atlee Populist movement, rise Positive liberty Post-Civil War price deflation Post-War economy, increase Post-WWII periods, segments (Morga) Pre-WWI America, libertarian world view Price deflation (post-Civil War) Private banks notes, printing paper issuance, suspicion U.S. government, relationship (change) Private businesses, bankruptcy (1873) Private debt financing level, peak (1929) usage Private gold, confiscation Private investment rate, decline Private parties, foreign lending (problem) Private sector debt levels rise economy, depression public sector, relationship Production, promotion Progressives disappointment movement impact marginalization Prohibition, repeal (Smith support) Protectionism, attraction Protestant silverites, characterization Public debt financing Public debt, Hamilton advocacy Public-private partnership, creation Public sector debt, growth private sector, relationship Pujo, Arsene P. Pujo Committee focus investigation reopening political context report, publication Purchasing power, promotion Pushing on a string Railroads asset choice banks/commercial companies, comparison collapse dominance, cessation post-Civil War debt Railway Labor Act, Supreme Court (upholding) Rainsford, W.S. Rand, Ayn (Greenspan disciple) Raskob, John J. Rayburn, Sam Raynes, Sylvain Reading Railroad bankruptcy corporate instability, cause debt, interest (payment) Reagan, Ronald deregulation promise supporters White House entry Reaganomics Real economic growth, average (Reagan years) Real estate bust (2007) Real wages, impact Recession Reconstruction, financial opportunity Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) authorization Baruch prediction Federal Reserve System, relationship government policy implementation Hoover creation intermediate credit facility control lending powers loans, usage Mills perspective operations, expansion parastatal corporation, Jones control role, importance Red Scare (1919-1920) Reed, John Reeves, Richard Reform, politics (Roosevelt/Wilson impact) Reinhart, Carmen (This Time It Is Different) Reis, Bernard J.

The Production of Money: How to Break the Power of Banks

by

Ann Pettifor

Published 27 Mar 2017

There are times, such as our own, when low rates of interest and other monetary policies are insufficient to stimulate the kind of investment needed to increase employment, improve productivity and generate income. That is when it is important for monetary policy to work hand in hand with fiscal policy. In other words, when monetary policy is like pushing on a string and the private sector is reluctant to invest and spend, then it is time for governments to initiate investment and spending – to create jobs, expand activity and income, and generate economic recovery, Austerity leads to shortages of safe assets Keynes understood that the rate of interest is a social variable, one that can be deliberately managed by the public authorities, while at the same time holding finance capital at bay.

The Finance Curse: How Global Finance Is Making Us All Poorer

by

Nicholas Shaxson

Published 10 Oct 2018

As John Maynard Keynes once put it, discussing financial globalisation and inequality in the oligarchical Gilded Age before the First World War (no relation of the Golden Age after the Second), ‘society was so framed as to throw a great part of the increased income into the control of the class least likely to consume it’. This three-trillion-dollar fact poses a large question for the tax cutters to answer. Why would a corporate tax reduction – adding to already vast uninvested cash piles – spur corporations to invest? Corporate tax cutting is like pushing on a string. And, given how quickly cash piles have been growing – a hefty 6 per cent a year, at the last count – any research based on past evidence can’t take this factor into account.21 How can our diligent researcher incorporate all this stuff into a serious cost-benefit analysis? She can’t. No one can.

…

For example, if large multinationals are sitting on trillion-dollar cash piles that they aren’t investing, why would any pro-multinational reform – whether cutting corporate taxes or financial regulations, but also reducing workers’ rights or wages, or relaxing environmental rules – suddenly encourage them to start? Such measures may quantifiably boost corporate profits, but in terms of attracting or stimulating real investment, they would be pushing on a string. And it’s worse than that, for the same reason I explained earlier. Because these measures take wealth out of the hands of workers and other less wealthy stakeholders in society – stakeholders who generally spend a greater share of any extra wealth that comes their way – this will tend to reduce overall demand, making it less likely that corporations will invest, inflicting a second round of damage.

Endless Money: The Moral Hazards of Socialism

by

William Baker

and

Addison Wiggin

Published 2 Nov 2009

The expansion of credit might be controlled some by those at the helm of the Fed, but the animal spirits of those who would lend and borrow are equally important, as was proven back in the times when there was no Fed and gold was the monetary base. If the horse has been run too hot (as it was in the 1920s), loosening the reins may not be enough to entice it to speed up again after the race is over. To borrow from an old saying, the Fed governors could not “push on a string.” Fiat money, electronic or paper currency that is not redeemable into a hard asset, has dominated the modern financial era. Cultural and political change has trended against prudent management of credit growth for nearly a century. As a consequence, outside a few doomsayers, libertarians, and boldly curious economists or money managers, most observers in our time have little more than a theoretical conception of why a fiat currency system could come under stress, and whether the current crisis might be handled effectively or deepen to the point that the political demand for an alternative form of money 74 ENDLESS MONEY would emerge.

…

Those who rooted for the deflationist camp looked to the depression years and saw a consumer heavily laden with debt and a highly leveraged banking system wherein over half of its loans relate to real estate.6 They saw interest rates at generational lows already, with the Fed discount rate near zero by year-end 2008. With loan demand sated and a need for banks and consumers to deleverage, they saw any Fed action to inject reserves into the monetary system as “pushing on a string,” to use the phrase invented by the monetarist Friedman in his analysis of the Great Depression. From within the Fed in the days that the policy of quantitative easing became official, Philadelphia Federal Reserve Bank President Plosser alerted us that “(recent economic statistics) prompted some commentators to suggest that the United States is facing a threat of sustained deflation, as we did in the Great Depression or as Japan faced for a decade.

The Shifts and the Shocks: What We've Learned--And Have Still to Learn--From the Financial Crisis

by

Martin Wolf

Published 24 Nov 2015

Certainly, apparently reasonable monetary growth, measured by M2, did not generate a vigorous recovery, though it almost certainly stopped a far deeper recession. The difficulty, as we saw in Chapter Five, is that the economy suffers from a savings glut – desired savings exceed desired investment, despite the extremely low interest rates. In the well-known expression: money is pushing on a string.47 Moreover, though the short-term rate may be near to or at zero, it is impossible to bring the long-term rate that low, because of ‘liquidity preference’: at negligible long-term rates, the downside for holders is large (since investors would lose a fortune if yields returned to normal) and the upside negligible.

…

M2 consists of (1) currency outside the US Treasury, Federal Reserve Banks, and the vaults of depository institutions; (2) travellers’ checks of non-bank issuers; (3) demand deposits; (4) other checkable deposits (OCDs), which consist primarily of negotiable order of withdrawal (NOW) accounts at depository institutions and credit-union share-draft accounts; (5) savings deposits (which include money-market deposit accounts, or MMDAs); (6) small-denomination time deposits (time deposits in amounts of less than $100,000); and (7) balances in retail money-market mutual funds (MMMFs). Definitions are available at http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2. 47. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pushing_on_a_string. 48. See, among many other things, Hyman P. Minsky, Stabilizing an Unstable Economy (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1986), and ‘Financial Instability and the Decline (?) of Banking: Future Policy Implications’, Working Paper No. 127, October 1994, The Jerome Levy Research Institute of Bard College, http://www.levyinstitute.org/pubs/wp127.pdf. 49.

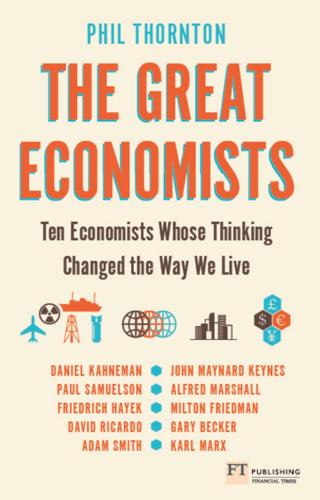

The Great Economists Ten Economists whose thinking changed the way we live-FT Publishing International (2014)

by

Phil Thornton

Published 7 May 2014

In any event governments cannot cut nominal interest rates below zero (otherwise they would have to pay people to borrow from them). 104 The Great Economists While interest rates may be good at containing an expansion by pulling monetary policy tighter, they are less effective in a downturn – summed up in the phrase attributed to Keynes of ‘pushing on a string’. In a depression people will not want to borrow but will hoard money in their banks rather than spend or borrow more. The mere fact that cheap money and cheap labour are available will not be sufficient to make businesses invest and expand if they do not wish to. Expectations and uncertainty If there is one concept at the heart of Keynes’s thinking and which marks a break with the classicists it is the role played by people’s uncertainty about the future.

Let My People Go Surfing

by

Yvon Chouinard

Published 20 Jun 2006

However ingeniously adaptive and self-healing nature may be, human industry, especially during the past century, wreaks change far more quickly than nature can deal with it. Where we tip the balance, we yield desert, and at some point we may tip the balance planet-wide. At that point all mitigating human effort becomes, in Keynes’s memorable phrase, “like pushing on a string.” We are the last generation that can experience true wilderness. Already the world has shrunk dramatically. To a Frenchman, the Pyrenees are “wild.” To a kid living in a New York City ghetto, Central Park is “wilderness,” the way Griffith Park in Burbank was to me when I was a kid. Even travelers in Patagonia forget that its giant, wild-looking estancias are really just overgrazed sheep farms.

Hubris: Why Economists Failed to Predict the Crisis and How to Avoid the Next One

by

Meghnad Desai

Published 15 Feb 2015

A recovery that was faster in the UK than in the US. This historical experience was somewhat ignored by the postwar fashion of simplifying Keynes’s message, leading to the rigid conclusion drawn by the earlier generation of Keynesians that monetary policy was ineffective in engineering a recovery. The adage was: “You cannot push on a string.” Yet the injection of a large quantity of liquidity has not revived the economies of the US and UK. The best you can say is that the recession was not deepened thanks to the regime of low interest rates. What is also surprising is that the enormous amount of money injected into the economy has not caused inflation, as was the doctrine of the monetarists during the 1970s.

Financial Market Meltdown: Everything You Need to Know to Understand and Survive the Global Credit Crisis

by

Kevin Mellyn

Published 30 Sep 2009

However, sometimes the problem is deeper, and even very cheap money doesn’t restore market confidence. Low interest rates are like a string the central bank can use to draw entrepreneurs and investors back into taking the kind of risks that produce jobs and generate wealth. As has often been noted, you can’t push on a string. Flooding the market with cheap money is totally ineffective if risks outweigh any obvious opportunities to make money. Cheap money is useless if nobody wants to use it or if those who want to use it no longer should have it because of the risk they represent. It is like pumping more and more air into a balloon that has burst.

Meltdown: How Greed and Corruption Shattered Our Financial System and How We Can Recover

by

Katrina Vanden Heuvel

and

William Greider

Published 9 Jan 2009

At the end of February, the huge insurer American International Group reported the largest quarterly loss, $5 billion, since the company started in 1919. After some delay, the Federal Reserve Board last summer started lowering interest rates on loans to the banks. But in a phrase from the bank crisis of the 1930s, it was like “pushing on a string.” The bankers’ problem was not that money was too expensive to lend out; it was that they were afraid they wouldn’t get their money back. When they did lend, they jacked up the rates to compensate for the higher perceived risks—even to solid customers. The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey suddenly had to borrow money at 20 percent.

How to Speak Money: What the Money People Say--And What It Really Means

by

John Lanchester

Published 5 Oct 2014

Economists and people who speak money argue all the time about things like inflation, not just in terms of what to do about it and its practical consequences but actually in terms of the very essence of what it is and how it works and how best to define it. Here is the range of views, as summarized by Wikipedia: Some economists maintain that high rates of inflation and hyperinflation are caused by an excessive growth of the money supply, while others take the view that under the conditions of a liquidity trap, large injections are “pushing on a string” and cannot cause significantly higher inflation. Views on which factors determine low to moderate rates of inflation are more varied. Low or moderate inflation may be attributed to fluctuations in real demand for goods and services, or to changes in available supplies such as during scarcities, as well as to changes in the velocity of money supply measures—in particular the MZM (money zero maturity) supply velocity.

The Age of Stagnation: Why Perpetual Growth Is Unattainable and the Global Economy Is in Peril

by

Satyajit Das

Published 9 Feb 2016

In November 2012, IMF chief economist Olivier Blanchard admitted that the impact of the unconventional monetary measures was both limited and uncertain. He acknowledged the minimal effect of the policies on business and consumer confidence, consumption, employment, and growth in incomes or credit.12 It was Keynes's liquidity trap, where policy is largely ineffective, analogous to pushing on a string. But central banks continued with the failed policies. In January 2015, the European Central Bank announced its own version of QE after over two years of prevarication. No one was convinced that it would create growth or inflation. Board members felt that they had to do something. Launching their umpteenth round of ineffective monetary stimuli, Japanese central bankers resorted to marketing, rebranding QE as QQE (qualitative and quantitative expansion).

Paper Money Collapse: The Folly of Elastic Money and the Coming Monetary Breakdown

by

Detlev S. Schlichter

Published 21 Sep 2011

This is bound to change as the channels through which money is injected broaden, and as more sectors become recipients of the central banks’ flow of money, either by directly receiving money from the central bank or by receiving central bank funded state transfers. The response of broader price level indices to this money printing will be more in accordance with what standard economic theory predicts: there will be rises in standard inflation measures. For some time inflationary policy may appear like “pushing on a string,” but there will be a point at which it will gain traction. The decline in money’s purchasing power will accelerate when the public realizes to what extent income streams, asset prices, and the solvency of the banks and state institutions rest on the ongoing printing of money. The rush out of paper money will then accelerate dramatically.

Straight Talk on Trade: Ideas for a Sane World Economy

by

Dani Rodrik

Published 8 Oct 2017

We will see whether Greeks’ evident desire to remain in the eurozone (or their fears of the alternative) will prove sufficient counterweight to the pain that the country has yet to endure. As desirable as broad structural reforms may be in the medium to long run, they do very little to solve the short‐run problem of inadequate demand. Dealing with this problem through supply‐side reforms aimed at increasing productivity is like pushing on a string. What is needed instead is some good old‐fashioned Keynesianism: policies to boost eurozone–wide demand and stimulate greater spending in creditor countries, especially Germany. Back to Politics and Democracy At the heart of this economic misdiagnosis is also the absence of EU‐wide democratic accountability.

Easy Money: Cryptocurrency, Casino Capitalism, and the Golden Age of Fraud

by

Ben McKenzie

and

Jacob Silverman

Published 17 Jul 2023

In 1932, Congress belatedly passed the Glass-Steagall Act, injecting $1 billion of cash into the banks by designating government securities as assets eligible to back the US dollar in addition to gold. But by then it was too late; credit kept shrinking at a rate of 20 percent a year. As Ahamed notes, “A similar measure in late 1930 or in 1931 might have changed the course of history. In 1932 it was like pushing on a string.” The economy continued in its tailspin, bottoming out in March 1933 as the commercial banking system collapsed. It would take years for the American economic engine to restart. Commitment to the gold standard did not cause the Great Depression, but adherence to it prolonged the extraordinary pain that ensued.

The Deficit Myth: Modern Monetary Theory and the Birth of the People's Economy

by

Stephanie Kelton

Published 8 Jun 2020

They cannot alter taxes or spend money directly into the economy, so the best they can do to promote employment is to try to establish financial conditions that will give rise to more borrowing and spending. Lower interest rates might work to induce enough new borrowing to substantially lower unemployment. But they might not. As Keynes famously observed, “You can’t push on a string.” What he meant was that the Fed can make it cheaper to borrow, but it cannot force anyone to take out a loan. Borrowing money puts companies and individuals on the hook for the debts they incur. Loans must be repaid out of future income, and there are good reasons why the private sector might be reluctant to increase its indebtedness at various stages of the business cycle.

Trillion Dollar Triage: How Jay Powell and the Fed Battled a President and a Pandemic---And Prevented Economic Disaster

by

Nick Timiraos

Published 1 Mar 2022

With an exterior of imposing Georgia marble, the four-story structure is known, appropriately, as the Marriner S. Eccles Building. Eccles didn’t rush to use the Fed’s considerable new power. He believed the Fed’s tools were better suited for slowing down an overheating economy than for jump-starting a contracting one. “One cannot push on a string,” he told lawmakers at hearings in 1935.3 In the years after Roosevelt’s initial reforms, “the Treasury usually led and the Federal Reserve usually followed,” historian Allan Meltzer wrote.4 After the attack on Pearl Harbor drew the United States into the Second World War, long-term Treasury yields jumped.

Keynes Hayek: The Clash That Defined Modern Economics

by

Nicholas Wapshott

Published 10 Oct 2011

Meanwhile, the Federal Reserve continued buying back government bonds to keep long-term interest rates low, causing the dollar’s value to diminish. Adding to the nation’s supply of money when companies were already awash with cash only confirmed the admonition by Marriner Eccles, Franklin Roosevelt’s Federal Reserve chairman, about the impotence of monetary policy as a stimulus; “You cannot push on a string,” that is, however much money you make available, you cannot force businesses to make investments. EIGHTEEN And the Winner Is . . . Avoiding the Great Recession, 2008 Onward So, eighty years after Hayek and Keynes first crossed swords, who won the most famous duel in the history of economics?

The Myth of the Rational Market: A History of Risk, Reward, and Delusion on Wall Street

by

Justin Fox

Published 29 May 2009

Through the 1920s, Keynes and Irving Fisher had been on a similar economic wavelength, sharing the belief that misguided monetary policies caused most economic problems. During the Depression, Keynes took things a step further. The remedy Fisher prescribed was to print more money. Keynes despaired that this would amount merely to “pushing on a string,” and argued that government needed to spend money to get the economy moving again. As a matter of economic policy, this was a big difference. In terms of economic theory, not so much. The doctrine that took Keynes’s name came to consist of the mathematical economics of rational individual choice (that is, Fisher’s economics), combined with a few less-than-elegant additions that attempted to represent the maladies of the national economy known as recession and depression.17 “This was not a perfect bicycle,” recalled one of the young Keynesians, Paul Samuelson, “but it was the best wheel in town.”18 The perfect bicycle that was mathematical equilibrium economics remained intact.

Crisis Economics: A Crash Course in the Future of Finance

by

Nouriel Roubini

and

Stephen Mihm

Published 10 May 2010

But the collective cuts did little to stimulate loans, much less consumption, investment, or capital expenditures, as market rates remained very high given the fear and uncertainty that gripped banks, households, and firms. Nor did these cuts arrest the slide toward deflation. Conventional monetary policy ceased to have sway over the markets. The metaphor of choice was that exercising monetary policy was like “pushing on a string.” It was useless. The reason was simple: the cuts in the Federal funds rate (or its equivalent in other countries) did not percolate throughout the wider financial system. Banks had money, but they didn’t want to lend it: uncertainty bred by the crisis, and concerns that many of their existing loans and investments would eventually sour, made them risk averse.

Why We Can't Afford the Rich

by

Andrew Sayer

Published 6 Nov 2014

They failed to increase their already low level of lending for productive investment by businesses. Meanwhile, aggregate demand was depressed by austerity policies, rising unemployment and people cutting back on spending to pay off their debts. From the point of view of economic regeneration, the bailouts were about as successful as ‘pushing on a string’.135 Governments that had to fund substantial bailouts put themselves at risk. Stagnant or shrinking economies also mean increased government debt, because revenues from taxes decline and welfare expenditure goes up as unemployment rises, all of which increase the risk of default. When this predictably resulted in a worsening of the credit rating of those countries, the financial elite demanded more cuts, particularly cuts borne by ordinary taxpayers.

European Spring: Why Our Economies and Politics Are in a Mess - and How to Put Them Right

by

Philippe Legrain

Published 22 Apr 2014

By 2011 inflation averaged 4.5 per cent, so real interest rates were minus 4 per cent. One might have expected such exceptionally generous borrowing terms to have sparked a recovery. But they didn’t, because when banks, households and companies all want to hoard money not part with it, monetary policy becomes largely ineffective. In a liquidity trap, it is like pushing on a string. Normally, when the Bank of England cuts its bank lending rate, the rate at which banks can borrow more generally also falls.428 Banks then tend to lend to people and companies more cheaply, which generally encourages both to borrow more and in time to spend or invest more. Lower interest rates also tend to push up the prices of shares, bonds, property and other assets, making investors feel wealthier and therefore more likely to spend.

Termites of the State: Why Complexity Leads to Inequality

by

Vito Tanzi

Published 28 Dec 2017

In many countries there have been far fewer genuine structural reforms than would have been desirable. At the same time the public debts have continued to grow (see Tanzi, 2016b). As mentioned earlier, in the last three decades the attitude toward the role of monetary policy in promoting economic stabilization has changed. It has changed from the earlier view, that “you cannot push on a string” or “you can take a horse to the river but you cannot make it drink,” to one that believes monetary policy can bring “great moderation” and that those who conduct monetary policy have become accomplished “maestros” who know how to use the right policy instruments. Central banks have come to be expected to play a growing role, with their monetary actions, in the stabilization of national economies.

Stress Test: Reflections on Financial Crises

by

Timothy F. Geithner

Published 11 May 2014

In an epic financial crisis that followed a major credit boom, easy money had much less power. Interest rates were already effectively zero; most banks had little ability and even less desire to lend; businesses had little desire to borrow; and consumers already had too much debt. As central bankers say, it felt like the Fed was pushing on a string. It had begun the first round of quantitative easing, or QE1, buying GSE mortgage bonds to help reduce the cost and increase the availability of mortgages. This was an innovative way to do monetary stimulus at a time when short-term rates were as low as they could go; the Fed would later expand the program to Treasuries to try to drive down long-term rates more generally.

Lords of Finance: The Bankers Who Broke the World

by

Liaquat Ahamed

Published 22 Jan 2009

The two new measures combined—the infusion of additional capital into the banking system and the injection of reserves—allowed the Fed finally to pump money into the system on the scale required. But Meyer had left it too late. A similar measure in late 1930 or in 1931 might have changed the course of history. In 1932 it was like pushing on a string. Banks, shaken by the previous two years, instead of lending out the money used the capital so injected to build up their own reserves. Total bank credit kept shrinking at a rate of 20 percent a year. Bankers and financiers, the heroes of the previous decade, now became the whipping boys. No one provided a better target than Andrew Mellon.

The Golden Passport: Harvard Business School, the Limits of Capitalism, and the Moral Failure of the MBA Elite

by

Duff McDonald

Published 24 Apr 2017

The School has of late added a course on Leadership and Corporate Accountability, and the description of the topics for examination within it sound like a direct repudiation of Jensen: “decisions that involve responsibilities to each of a company’s core constituencies—investors, customers, employees, suppliers, and the public,” with discussions on insider trading rules, the fall of Enron, human character, employee responsibilities, labor laws, corporate citizenship, socially responsible investing, and serving the public interest. But in this, its influence can clearly be seen as akin to pushing on a string. “[While] the average firm has assiduously applied the agency theory principles that increase corporate entrepreneurialism and risk,” write Frank Dobbin and Jiwook Jung in their 2010 paper, “The Misapplication of Mr. Michael Jensen: How Agency Theory Brought Down the Economy and Might Do It Again,” “it has not applied the principles that bolster monitoring and foster executive self-restraint.

Conspiracy of Fools: A True Story

by

Kurt Eichenwald

Published 14 Mar 2005

In early January 2001, Skilling and Baxter stood on the ground level of an Enron parking garage, smoking. Baxter dropped the butt to the ground, crushing it with his foot. He was cranky and frustrated, like he’d been most days in the months since the end of Project Summer. Every other sales effort had bombed out. “This is like pushing on a string, Jeff,” he said. “I’m not getting anywhere.” “We’re going to have to keep plugging,” Skilling replied. The international projects had to be sold. Baxter shook his head. “You don’t need me to do this,” he said. “I’m not having any fun doing this.” He breathed deeply. “Jeff, I think it’s probably time for me to go,” he said.