Competition Overdose: How Free Market Mythology Transformed Us From Citizen Kings to Market Servants

by

Maurice E. Stucke

and

Ariel Ezrachi

Published 14 May 2020

Why Can’t the Victims De-escalate the Race to the Bottom? We now confront the penultimate missing piece of the puzzle. In situations where the competitors’ individual and collective interests diverge, we can have a race to the bottom that even powerful competitors cannot stop. But in many markets the beneficiaries of competition have a choice. They can stop this toxic competition by opting out. So why don’t they? One problem is that the intended beneficiaries of competition may be trapped in their own arms race. Rather than prevent (or at least slow down) the race to the bottom, they may actually accelerate the downward spiral.

…

When it does, it often leaves individuals and society worse off. The invisible hand then becomes nothing more than a sleight of hand. So when is competition a race to the bottom rather than to the top? There are two basic circumstances in which that happens: FIRST, when the competitors’ individual interests are not aligned with their collective interests, or with society’s collective interests. SECOND, when either the competitors or the intended beneficiaries of competition—or both—are harmed by this race to the bottom, but no one can independently de-escalate it. This may sound complex, but once we understand these two conditions, we’ll recognize many examples of toxic competition around us.

…

But in one case competition produced results that were toxic to all, in the other, beneficial to all. To distinguish between good and bad competition, between races to the top and races to the bottom, we must ask whether the competitors’ individual and collective interests are aligned. Basically, if all the competitors do the same thing, do they end up collectively better off—or worse? So when you are seeking an edge over a rival, consider what will happen if others follow your lead and take similar measures. If everyone ends up worse off, with no advantage going to anyone, you’re in a race to the bottom that benefits neither you nor society. When Competition Harms Its Intended Beneficiary: Public School Education In our simple scenario of helmetless hockey players, the arms race harms primarily the competitors themselves.

Economic Dignity

by

Gene Sperling

Published 14 Sep 2020

Structuring markets to reward competition principally on quality, price, and performance, and not race-to-the-bottom behavior, can lead competitive actors to focus on the elements that deliver better products and services to consumers and other stakeholders, without the concern that treating workers, consumers, and the environment with a level of basic decency might jeopardize their competitive advantage. Of course, rules that encourage high-road competition might impede profit margins compared to existing practices, where there is an open lane toward race-to-the-bottom competition. To the extent a textile manufacturer’s profit margins require forcing workers to labor in extremely dangerous factories or rely on suppliers using ten-year-olds in Vietnam, regulations that limit these practices will reduce the company’s profit margins.

…

When our nation had its breakdown of all common sense on housing finance, there was likely little room for a virtuous midlevel employee in 2006 to refuse to engage in such reckless subprime lending, because the market was structured to reward his competitors and peers at his own company for race-to-the-bottom competition. Virtuous employees may have indeed lost promotions, bonuses, and even their jobs. Structuring markets to prevent race-to-the-bottom competition ensures that we do not create business environments where no good deed and virtue go unpunished. PUNCHING STEPHEN CURRY As a thought experiment, imagine a slightly altered set of rules and regulations for the National Basketball Association (NBA).

…

Taunting players to waste one of the permitted punches would be refined to an art form. While perhaps this rule would have brought more Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) fans to basketball, most true basketball lovers would consider this a vicious race to the bottom. Those most effective in knocking out Curry or James—those who raced to the bottom—would have a serious leg up in pursuit of NBA championships. In this scenario, there would be little room for virtue going unpunished. Members of any given NBA team might find this barbaric and prefer to refrain. Yet such Gandhi-like responses to the punching rule would likely not be well received.

The Raging 2020s: Companies, Countries, People - and the Fight for Our Future

by

Alec Ross

Published 13 Sep 2021

“Europe did this to itself,” Schmidt stated, noting that the Europeans themselves created the “race to the bottom” tax treatment for a then-struggling Ireland to stimulate investment there. “The global tax system is incredibly complicated, and we are required to follow the tax rules,” he continued. “When the tax rules change, of course we would adopt them. But there was a presumption that somehow we were doing something wrong here.” Schmidt is correct. For whatever finger wagging may be directed against him and Google, the culpability rests principally with the countries that enable these activities by making them legal in the first place in the race to the bottom. Still, just because something is legal does not make it right.

…

The incentives drive companies toward share buybacks instead of investments in workers, equipment, and research and development. The incentives drive businesses to grow bigger through mergers and acquisitions, and then to fire rather than hire. And as we will read, the incentives encourage breaking up unions and sending headquarters to tax-optimized locales instead of to communities that are not in a race to the bottom on taxes. The incentives mean refusing to pay even a cent more for renewable energy than for fossil fuels. The nightmare is that all this optimization for nonproductive uses of capital and for the short term ensures that the long term will be worse for all of us. The inequality and climate crises we are already suffering from are direct consequences of optimizing for the short-term shareholder gains decades ago.

…

In the same way that GAAP provide a structure for determining a company’s tax burden, structures could be created that implement a similar set of measures for stakeholder impact and then provide the data to adjust a company’s taxes higher or lower. Companies respond to incentives, so we need to provide incentives for them to stop the race to the bottom on everything from environmental damage to workers’ rights. Former Bank of England governor Mark Carney has suggested that this approach be extended to executive compensation as well, saying that banks should link executive pay to climate risk management. The more a company does to contribute to goals set out in the Paris climate accord, the more its executives get paid.

Mastering the Market Cycle: Getting the Odds on Your Side

by

Howard Marks

Published 30 Sep 2018

Thus an overheated auction in the credit market—as elsewhere—is likely to produce a “winner” who’s really a loser. This is the process I call the race to the bottom. On the other hand, there are times when buyers show up for auctions in small numbers, and the few who do attend are interested in buying only at giveaway prices. The bidding stalls, and the result is low prices, eye-popping yields, and loan structures that afford excellent protection. Unlike the overheated climate that spawns the race to the bottom, ice-cold markets in which no one’s eager to lend can create real winners. The degree of openness of the credit window depends almost entirely on whether providers of capital are eager or reticent, and it has a profound impact on economies, companies, investors, and the prospective return and riskiness of the investment opportunities that result.

…

Perhaps most importantly among the contributing factors, the period was marked by risky behavior on the part of financial institutions. When the world is characterized by benign macro events, hyper-financial activity and financial innovation, there is a tendency for providers of capital to compete for market share in a process I call “the race to the bottom” (I’ll make reference later on to a memo of that name). The mood in the years 2005–07 was summed up by Citigroup CEO Charles Prince in June 2007, virtually on the eve of the Global Financial Crisis, in a statement that became emblematic of the era: “When the music stops, in terms of liquidity, things will be complicated.

…

This kind of risk tolerance and risk obliviousness plays an essential part in the up-phase that precedes—and sets the scene for—every dramatic down-phase. As the period 2005–07 was rolling along, it presented a great opportunity to observe events that made manifest market participants’ attitudes toward risk, and to reach helpful conclusions. I believe the following excerpt from “The Race to the Bottom,” a memo I wrote on the subject in February 2007—just a few months before the first indication that bad times were coming—provides an excellent example. It demonstrates the potential value of inferences drawn from isolated and perhaps anecdotal experiences: While the last few years have given me many opportunities to marvel at excesses in the capital markets, in this case the one that elicited my battle cry—“that calls for a memo”—hit the newspapers in England during my last stay.

The Finance Curse: How Global Finance Is Making Us All Poorer

by

Nicholas Shaxson

Published 10 Oct 2018

‘It is one of the biggest dark continents in economics.’ The answer to the second of my three questions for policymakers then is clear: ‘competition’ between states on corporate taxes is indeed a race to the bottom which increases inequality and harms the world at large. The third question is bigger, in fact it is one of the great economic questions of all time. It is this: whether or not ‘competition’ is a harmful race to the bottom that hurts the world at large, does it make sense for my country or state to ‘compete’ from the perspective of local self-interest? Schreck used to think not, at least for his area, but now he seems less certain.

…

When the world finally started to wake up to Tiebout’s paper, the year after his death, it would kick off a debate about one of the most important questions in the modern global economy: what happens when rich people, banks, multinational firms or profits shift across borders in response to different incentives like corporate tax cuts, financial deregulation and so on? This debate goes to the heart of questions around what has been called the competitiveness of nations, and whether competing on things like corporate tax cuts or environmental standards is a good thing or an unhealthy race to the bottom. In the end, Tiebout’s ideas would end up magnified, then distorted and used as ideological underpinning for a wide range of policies that generate the finance curse. Which is not what the leftist Charlie Tiebout would have wanted at all. History shows that inequality usually only gets properly upended after large, violent shocks.8 For Tiebout’s generation, it was the Second World War that provided the shock.

…

Rather than demonstrating how governments could ‘compete’ with each other and thus be efficient, as he had once thought, the emerging ‘competition’ between the states was revealing itself to be a powerful tool for big financial and corporate interests to get what they wanted from states and nations by playing them off against each other in a vicious race to the bottom. (For the rest of this book, I will call this latter form ‘competition’ – in inverted commas – as opposed to competition in private markets). In 1973, just four years after Oates published his paper, Idaho’s Democrat governor Cecil Andrus had a meeting with David Packard, the boss of the fast-growing computer company Hewlett-Packard.

Rewriting the Rules of the European Economy: An Agenda for Growth and Shared Prosperity

by

Joseph E. Stiglitz

Published 28 Jan 2020

Corporations care about their after-tax return, so they are sensitive not just to wages, the efficiency of labor, the overall business environment, transport costs, and other factors of production, but also to the taxes they have to pay. In the very short run, the one variable countries can change to attract businesses is the corporate income tax rate. Economists predicted that this would result in a race to the bottom, as companies could produce in a low-tax jurisdiction but enjoy access to the entire European Union and its markets. We see evidence of this race to the bottom. Between 1995 and 2018, the average corporate income tax rates for the EU went down from 35 percent to 22 percent.9 This trend can be expected to continue as France, Greece, the Netherlands, and Sweden have already announced further reductions of corporate income tax rates.10 By offering lower tax rates, countries gain jobs and some tax revenues, perhaps less than at higher tax rates, but the increased tax base, they hope, more than compensates.

…

Before that, the main voices heard were those of the bankers themselves, who had argued that loosening regulations would create a more dynamic financial system, which would contribute to a stronger European economy from which all would benefit. Besides, the bankers argued, there was a global marketplace into which they, their profits, and their jobs would disperse unless there was deregulation. Indeed, around the world, there was a race to the bottom as countries competed to attract the attention of footloose bankers. As neoliberals talked about the supposed growth and employment benefits of deregulation, they neglected the costs—both the macroeconomic risks that might arise from a poorly regulated financial sector that is engaged in excessive risk taking, and the microeconomic costs arising from the financial sector’s exploitation of its market power and consumer and investor ignorance.

…

With all that money to invest on behalf of savers, European asset managers—out to prove themselves better than their competitors in the easy, short-term metric of returns without adequate regard to risk—were only too happy to buy all manner of securities issued by banks. The credit rating agencies played a critical role in this scam, as they gave AAA ratings to securities that did not deserve them, engaging in massive fraud in a race to the bottom with other rating agencies. Wholesale funding (versus the retail approach of wooing depositors) exploded in Europe even more than in the United States. In 2008, it amounted to 60 percent of total funding for the largest 16 banks in Europe. This was twice as high as for large US banks.9 Banks also saw an opportunity to increase their activities as so-called market makers, by holding inventories of securities, standing ready to buy and sell and making a profit from the buy-sell spreads.

The Triumph of Injustice: How the Rich Dodge Taxes and How to Make Them Pay

by

Emmanuel Saez

and

Gabriel Zucman

Published 14 Oct 2019

The breaks that tax havens offer to big companies impose a cost on the rest of us, a “negative externality” in economics lingo. They feed a race to the bottom, leading to a world where, to prevent capital from moving abroad, most nations are compelled to adopt tax rates that are too low—lower than the rates they would otherwise democratically choose. The fundamental problem behind the current forms of international coordination is that they do not tackle, and in fact legitimize, the undemocratic forces of tax competition. And indeed, tax competition has intensified since the start of the BEPS process, and the global race to the bottom in corporate tax rates has accelerated. Since 2013, Japan cut its rate from 40% to 31%; the United States from 35% to 21%; Italy from 31% to 24%; Hungary from 19% to 9%; a number of Eastern European states are following the same route.

…

Their capital is intangible, it can move to Bermuda in a nanosecond. Other countries have low tax rates? We must have low rates. Other countries are giving up on taxing multinational companies and high earners? We must give up too. Tax coordination among countries is a utopia and the only future is a race to the bottom. No matter how sincerely held they may be, no matter how widely shared, these beliefs are incorrect. Instead of engaging in a giant fiscal free-for-all, we can coordinate our policies, as we’ve successfully done in many other areas of international relations. Rest assured, we know that some countries and social groups derive large benefits from globalization in its current form—but other forms are possible.

…

We will study, in the pages that follow, the arithmetic of tax competition and the central role it has played in the prosperity of a few. But we’ll also see how a handful of countries acting together could whistle the end of this game. We will see how defensive measures could be taken against tax havens, and how today’s race to the bottom can be replaced by a race to the top. The notion that external or technical constraints—“international competition,” “tax avoidance,” “loopholes”—make tax justice idle fantasy does not withstand scrutiny. When it comes to the future of taxation, everything is possible. From the disappearance of the income tax—a plausible outcome if the trend of the last four decades is sustained—to levels of progressivity never seen before, there is an infinity of possible futures ahead of us.

Open: The Progressive Case for Free Trade, Immigration, and Global Capital

by

Kimberly Clausing

Published 4 Mar 2019

For example, if multinational mining companies respond to environmental regulations by forsaking countries with environmental regulations in favor of countries that allow environmentally hazardous production methods, that can lead to a “race to the bottom,” where countries try to outdo one another by lowering regulatory burdens and cutting taxes in hopes of winning businesses’ favor. Evidence suggests that a race to the bottom may be of particular concern in the case of extractive industries such as oil drilling and mining, especially in developing countries. In the past, this race to attract extractive industries has led to excessive resource depletion and toxic pollution, made all the more painful by disappointing gains in job creation and economic growth.21 It is important to note that disparate environmental regulations do not necessarily trigger a race to the bottom.

…

In these two areas, current trade agreements strike many as too broad. Yet despite these important examples, there are also ways in which broader agreements may make good sense. For example, if countries are concerned about tax or regulatory competition, international agreements offer a means to avoid a “race to the bottom.” Governments could use agreements to commit to higher standards, reducing global companies’ ability to pit governments against each other. Shunning the Trans-Pacific Partnership In a New York Times poll back in May 2015, 78 percent of respondents said they knew “not much” or “nothing at all” about the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP).

…

In the past, this race to attract extractive industries has led to excessive resource depletion and toxic pollution, made all the more painful by disappointing gains in job creation and economic growth.21 It is important to note that disparate environmental regulations do not necessarily trigger a race to the bottom. For example, a multinational company that needs to comply with a higher-standard jurisdiction may find it more cost-effective to use one uniform production method throughout its operations. By employing the cleaner production method in lower-standard jurisdictions, it helps to spread cleaner technologies and methods throughout the world. In just this way, higher clean air standards in California caused US automotive companies to improve their environmental performance throughout the entire US market.

Straight Talk on Trade: Ideas for a Sane World Economy

by

Dani Rodrik

Published 8 Oct 2017

In economic models of “monopolistic competition,” producers compete not just on price but on variety—by differentiating their products from others’.32 Similarly, national jurisdictions can compete by offering institutional “services” that are differentiated along the dimensions I discussed earlier. One persistent worry is that institutional competition sets off a race to the bottom. To attract mobile resources—capital, multinational enterprises, and skilled professionals—jurisdictions may lower their standards and relax their regulations in a futile dynamic to outdo other jurisdictions. Once again, this argument overlooks the multidimensional nature of institutional arrangements.

…

Similarly, higher labor standards may lead to happier and more productive workers; tougher financial regulation to greater financial stability; and higher taxes to better public services, such as schools, infrastructure, parks, and other amenities. Institutional competition can foster a race to the top. The only area in which some kind of race to the bottom has been documented is corporate taxation. Tax competition has played an important role in the remarkable reduction in corporate taxes around the world since the early 1980s. In a study on OECD countries, researchers found that when other countries reduce their average statutory corporate tax rate by 1 percentage point, the home country follows by reducing its tax rate by 0.7 percentage points.33 The study indicated that international tax competition takes place only among countries that have removed their capital controls.

…

When such controls are in place, capital and profits cannot move as easily across national borders and there is no downward pressure on capital taxes. So, the removal of capital controls appears to be a factor in driving the reduction in corporate tax rates. On the other hand, there is scant evidence of similar races to the bottom in labor and environmental standards or in financial regulation. The geographically confined nature of the services (or public goods) offered by national jurisdictions often presents a natural restraint on the drive toward the bottom. If you want to partake of those services, you need to be in that jurisdiction.

Treasure Islands: Uncovering the Damage of Offshore Banking and Tax Havens

by

Nicholas Shaxson

Published 11 Apr 2011

The end result was that the biggest banks were able to grow large enough to attain “too big to fail” status—which helped them in turn to become increasingly influential in the bastions of political power in Washington, eventually getting a grip on both main political parties, Democrat and Republican—a grip that is so strong that it amounts to political capture. Part of this process has involved a constant race to the bottom between jurisdictions. When a tax haven degrades its taxes or financial regulations or deepens its secrecy facilities to attract hot money from elsewhere, other havens degrade theirs too, to stay in the race. Meanwhile, financiers threaten politicians in the United States and other large economies with the offshore club—“don’t tax or regulate us too heavily or we’ll leave,” they cry—and the onshore politicians quail and relax their own laws and regulations.

…

Deregulation, freer flows of capital, and lower taxes since the 1970s—most people think that these globalizing changes have resulted primarily from grand ideological shifts and deliberate policy choices ushered in by such leaders as Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan. Ideology and leaders matter, but few have noticed this other thing: the role of the secrecy jurisdictions in all of this—the silent warriors of globalization that have been acting as berserkers in the global economy, forcing other nations to engage in the competitive race to the bottom, and in the process cutting swaths through the tax systems and regulations of nation states, rich and poor, whether they like it or not. The secrecy jurisdictions have been the heart of the globalization project from the beginning. Finally, a word about culture and attitudes. In January 2008 the accountancy giant KPMG ranked Cyprus at the very top of a league table of European jurisdictions, according to the “attractiveness” of their corporate tax regimes.53 Yet Cyprus, a “way station for international scoundrels,” as one offshore promoter admits, is among the world’s murkiest tax havens: possibly the biggest conduit for criminal money out of the former Soviet Union and the Middle East into the international financial system.

…

The notorious “merchant of death” Viktor Bout, inspiration for the character played by Nicholas Cage in the Hollywood film Lord of War, alleged arms runner to the Taliban and other murderous organizations around the globe, operated through businesses in Texas, Delaware, and Florida.27 “US shell companies are attractive vehicles for those seeking to launder money, evade taxes, finance terrorism, or conduct other illicit activity anonymously,” said Republican Senator Norm Coleman, then chairman of the U.S. Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations. “Competition among States to attract company filing revenue and franchise taxes has, in some instances, resulted in a race to the bottom.”28 A New York Times article from 1986 describes the antics of one Delaware lieutenant-general who flew to Taiwan, Hong Kong, China, Indonesia, Singapore, and the Philippines, clutching a pamphlet boasting that Delaware could “Protect You from Politics.”29 The official was, the article noted, “looking forward to a rich harvest of Hong Kong flight capital” after the British pullout in 1997.

Four Battlegrounds

by

Paul Scharre

Published 18 Jan 2023

Horowitz and Lauren Kahn, “Why DoD’s New Approach to Data and Artificial Intelligence Should Enhance National Defense,” Council on Foreign Relations blog, March 11, 2022, https://www.cfr.org/blog/why-dods-new-approach-data-and-artificial-intelligence-should-enhance-national-defense; Jaspreet Gill, “Say Goodbye to JAIC and DDS, As Offices Cease to Exist As Independent Bodies June 1,” Breaking Defense, May 24, 2022, https://breakingdefense.com/2022/05/say-goodbye-to-jaic-and-dds-as-offices-cease-to-exist-as-independent-bodies-june-1/. 252technical innovation: Ian Goodfellow and Nicolas Papernot, “The Challenge of Verification and Testing of Machine Learning,” cleverhans-blog, June 14, 2017, http://www.cleverhans.io/security/privacy/ml/2017/06/14/verification.html. 253Patriot air and missile defense system: For more on the Patriot fratricides, see Paul Scharre, Army of None: Autonomous Weapons and the Future of War (New York: W. W. Norton, April 24, 2018), 137–145. 31. RACE TO THE BOTTOM 254“race to the bottom”: Portions of this chapter are adapted, with permission, from Paul Scharre, “Debunking the AI Arms Race Theory,” Texas National Security Review 4, no. 3 (Summer 2021): 121–132, http://dx.doi.org/10.26153/tsw/13985. 254“move fast and break things”: Steven Levy, “Mark Zuckerberg on Facebook’s Future, from Virtual Reality to Anonymity,” Wired, April 30, 2014, https://www.wired.com/2014/04/zuckerberg-f8-interview/. 254“We are under so much pressure”: Jack Shanahan, interview by author, April 1, 2020. 254twenty-five years from initial concept: F-35 Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) Program (Congressional Research Service, updated May 27, 2020) https://fas.org/sgp/crs/weapons/RL30563.pdf; The Joint Advanced Strike Technology (JAST) program, which later became the Joint Strike Fighter program, was created in 1993.

…

—CHINESE GENERAL SECRETARY XI JINPING CONTENTS LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS PREFACE INTRODUCTION PART I POWER 1.THE NEW OIL 2.DATA 3.COMPUTE 4.TALENT 5.INSTITUTIONS PART II COMPETITION 6.A WINNING HAND 7.MAVEN 8.REVOLT 9.SPUTNIK MOMENT PART III REPRESSION 10.TERROR 11.SHARP EYES 12.A BETTER WORLD 13.PANOPTICON 14.DYSTOPIA PART IV TRUTH 15.DISINFORMATION 16.SYNTHETIC REALITY 17.TRANSFORMATION 18.BOT WARS PART V RIFT 19.FUSION 20.HARMONY 21.STRANGLEHOLD PART VI REVOLUTION 22.ROBOTICS ROW 23.PROJECT VOLTRON 24.FOUNDATION 25.THE WRONG KIND OF LETHALITY 26.JEDI 27.DISRUPTION PART VII ALCHEMY 28.CONTROL 29.POISON 30.TRUST 31.RACE TO THE BOTTOM PART VIII FIRE 32.ALIEN INTELLIGENCE 33.BATTLEFIELD SINGULARITY 34.RESTRAINT 35.THE FUTURE OF AI CONCLUSION ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ABBREVIATIONS NOTES INDEX LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Deep Neural Network U.S. R&D Funding as a Percentage of Gross Domestic Product, 1953–2018 U.S. Share of Global R&D (1960) U.S.

…

Systems may work brilliantly in one setting, then fail dramatically if the environment slightly changes. The “black box” nature of many AI methods means that it may be difficult to accurately predict when they will fail or even understand why they failed in retrospect. Potentially even more dangerous, the global competition in AI risks a “race to the bottom” on safety. In a desire to beat others to the punch, countries may cut corners to deploy AI systems before they have been fully tested. We are careening toward a world of AI systems that are powerful but insecure, unreliable, and dangerous. But technology is not destiny, and there are people around the world working to ensure that technological progress arcs toward a brighter future.

The Undercover Economist: Exposing Why the Rich Are Rich, the Poor Are Poor, and Why You Can Never Buy a Decent Used Car

by

Tim Harford

Published 15 Mar 2006

We saw in chapter 4 that the economist’s concept of externalities gives us a powerful tool to appreciate the risks of environmental damage, and externality charges give us a solution. Many—perhaps most—economists understand the risks of environmental damage and want action to preserve the environment. But the link between trade and environmental damage just doesn’t stand up to close scrutiny. There are three reasons for concern. The first concern is of a “race to the bottom”: companies rush overseas to produce goods under cheaper, more lenient environmental laws, while hapless governments oblige them by creating those lenient laws. The second is that physically moving goods around inevitably consumes resources and causes pollution. The third worry is that if trade promotes economic growth, it must also harm the planet.

…

The environmentalist Vandana Shiva speaks for many when she declares that “pollution moves from the rich to the poor. The result is a global environmental apartheid.” Strong words—but are they true? In theory, they might be true. Companies that can produce goods more cheaply will be at a competitive advantage. They can also move around more easily in a world of free trade. So the “race to the bottom” is a possibility. Then again, there are reasons to suspect that it’s a fantasy. Environmental regulations are not a major cost; labor is. If American environmental standards are really so strict, why do the most pollution-intensive American firms spend only 2 percent of their revenues on dealing with pollution?

…

As an analogy: if ten-year-old computer chips were still produced in bulk, they would be simpler and cheaper to make than modern chips, but nobody bothers any more. It’s now hard to buy an old computer even if you want to. And these arguments leave aside the possibility that firms want to offer high environmental standards to please their workers and their customers. So . . . a “race to the bottom” is possible in theory; but there are also good grounds for doubting its existence. So leaving theory to one side, what are the facts? First, that foreign investment in • 215 • T H E U N D E R C O V E R E C O N O M I S T rich countries is far more likely to go into polluting industries than foreign investment in poor countries.

Everything Bad Is Good for You: How Popular Culture Is Making Us Smarter

by

Steven Johnson

Published 5 Apr 2006

It i s a truth nearly universally acknowledged that pop culture caters to our base instincts; mass society dumbs down and simplifies; it races to the bottom. The rare flowerings of "quality programming" only serve to remind us of the over all downward slide. But no matter how many times this re frain is belted out, it doesn't get any more accurate. As we've seen, precisely the opposite seems to be happening: the sec ular trend is toward greater cognitive demands, more depth , more participation. And if you accept that premise, you ' re forced then to answer the question : Why? For decades, the race to the bottom served as a kind of Third Law of Thermodynamics for mass society : all other things being equal, pop culture will decline into simpler forms.

…

Melodrama's good, you know, a little tear here and there, a little morality tale, that's good. Positive. That's least objectionable. It's my job to keep my 32, not to cause any tune-out a priori in terms of ads or concepts, to make sure there's no tune-out in the shows vis-a-vis the competition. LOP is a pure-breed race-to-the-bottom model : you cre ate shows designed on the scale of minutes and seconds, with the fear that the slightest challenge-"thought, " say, or "education"-will send the audience scurrying to the other networks. Contrast LOP with the model followed by The Sopranos-what you might call the Most Repeatable Pro- 162 ST E V E N J O H N SO N gramming model.

…

It's cruci al that we abandon the Brave New World scenario where mindless amusement always wins out over more chal lenging fare , that we do away once and for all with George Wi l l 's vision of an "increasingly infantilized society. " Pop E V E R Y T H I N G B A D I S G O O D F O R Yo u 1 85 culture is not a race to the bottom, and it's high time we accepted-even celebrated-that fact. But even the most salutary social development comes with peripheral effects that are less desirable. The rise of the Internet has forestalled the death of the typographic universe-and its replacement by the society of the image-predicted by McLuhan and Postman.

Model Thinker: What You Need to Know to Make Data Work for You

by

Scott E. Page

Published 27 Nov 2018

Lyapunov Theorem Given a discrete time dynamical system consisting of the transition rule xt+1 = G(xt), the real-valued function F(xt) is a Lyapunov function if F(xt) ≥ M for all xt and if there exists an A > 0 such that If F is a Lyapunov Function for G, then starting from any x0, there exists a t∗, such that G(xt∗) = xt∗, and the system attains an equilibrium in finite time. We first construct a Lyapunov function within the Race to the Bottom Game, which captures strategic environments in which players choose levels of support such that each player prefers to provide just less than the average level. The Race to the Bottom Game Each of N players proposes a level of support in {0, 1,… 100} in each period. The player closest to of the average level of support wins a prize in that period. The game can be used to explain reductions in state government spending for social programs such as support for the indigent.

…

It is straightforward to show that the maximum level of support from any player satisfies the conditions for a Lyapunov function. The maximum level of support has a minimum at zero. And in each period the maximum level of support falls by at least 1 given that levels of support take integer values. Thus, at some point, everyone proposes zero support. The players have raced to the bottom. In this example, the model produces an undesirable result. To prevent a race to the bottom requires changing the game. To increase support for the indigent, a federation could shift to federal funding or impose a floor on spending.2 As an aside, suppose that we allow players to choose any real number in the interval between zero and 100 rather than integer values.

…

You will learn to identify when you are allowing ideology to supplant reason and have richer, more layered insights into the implications of policy initiatives, whether they be proposed greenbelts or mandatory drug tests. These benefits will accrue from an engagement with a variety of models—not hundreds, but a few dozen. The models in this book offer a good starting collection. They come from multiple disciplines and include the Prisoners’ Dilemma, the Race to the Bottom, and the SIR model of disease transmission. All of these models share a common form: they assume a set of entities—often people or organizations—and describe how they interact. The models we cover fall into three classes: simplifications of the world, mathematical analogies, and exploratory, artificial constructs.

The Best Way to Rob a Bank Is to Own One: How Corporate Executives and Politicians Looted the S&L Industry

by

William K. Black

Published 31 Mar 2005

“COMPETITION IN LAXITY” Economists describing how regulators competed for “customers” by promising to be laxer in supervision coined two of the most telling phrases to come out of the S&L debacle: “competition in laxity” and “race to the bottom.” The novel aspect is that economists endorsed these pejorative terms because the race was toward greater deregulation. In the early 1980s, economists knew that regulation was the problem, so anything that reduced regulation was desirable. Richard Pratt shared this mindset when President Reagan appointed him Bank Board chairman in 1981. FOR THE BANK BOARD, THE RACE TO THE BOTTOM WAS A SHORT ONE The Bank Board was at the bottom of the federal financial regulatory heap before Pratt’s deregulation and desupervision.

…

The goodwill mergers and the wave of new entrants that Pratt encouraged diverted critical supervisory resources into (non)resolutions at precisely the time they were desperately needed to counter the wave of control frauds. TEXAS AND CALIFORNIA—THE STATES THAT WON THE RACE TO THE BOTTOM Another term for “competition in laxity” was “the race to the bottom.” S&Ls could change freely from a federal to a state charter (the permission from the government to run an S&L) and still be insured by the FSLIC. The charter determined what the S&L could invest in. Texas led the race by deregulating in the 1970s, and California followed the lead.

…

Texas had the equivalent of a “most favored nation” clause in its charters that allowed Texas-chartered S&Ls to do whatever federally chartered ones could, so the rush to convert to federal charters was greatest in California. California responded to the Garn–St Germain Act with the Nolan Act (named after its sponsoring senator, the notably corrupt and soon-to-be-convicted Pat Nolan). The Nolan Act became effective on January 1, 1983. It won the race to the bottom by going directly to the bottom. A California-chartered S&L could invest 100 percent of its assets in anything (with the commissioner’s approval). Despite Nolan’s corruption, this was not a conspiracy, but a bungled mess of epic proportions. No one was clever enough to design this disaster.

The Euro: How a Common Currency Threatens the Future of Europe

by

Joseph E. Stiglitz

and

Alex Hyde-White

Published 24 Oct 2016

But this rigid application of rules, in the absence of common deposit insurance, may make it even riskier for depositors to keep their money in the banks of a weak country: it may exacerbate the problem of divergence. REGULATORY RACES TO THE BOTTOM Europe not only allowed capital to flow freely within its borders but also financial firms and products—no matter how poorly they are regulated at home. The single-market principle for financial institutions and capital, in the absence of adequate EU regulation, led to a regulatory race to the bottom, with at least some of the costs of the failures borne by other jurisdictions. The failure of a financial institution imposes costs on others (evidenced so clearly in the crisis of 2008), and governments will not typically take into account these “cross-border costs.”

…

The EU (and this analysis thus goes beyond the eurozone) must adopt two further sets of policies: First, it needs to limit the race to the bottom, the kind of tax competition that worked so well for a few countries like Luxembourg but at the expense of others. This is a real example of an externality—of an action by one country that imposes harms on others. And yet Europe has failed to take adequate action, partially because many in Europe are enamored of the idea of low taxes and a small state, and this kind of race to the bottom suits them fine. Secondly, given the easy mobility around the European Union, the major responsibility for redistribution must lie at the EU level.39 The EU should follow the United States in levying taxes based on citizenship, wherever individuals are domiciled or resident.

…

The failure of a financial institution imposes costs on others (evidenced so clearly in the crisis of 2008), and governments will not typically take into account these “cross-border costs.” Indeed, especially before the 2008 global financial crisis, each country faced pressures to reduce regulations. Financial firms threatened that they would leave unless regulations were reduced.14 This regulatory race to the bottom would have existed within Europe even without the euro. Indeed, the winners in the pre-2008 contest were Iceland and the UK, neither of which belong to the eurozone (and Iceland doesn’t even belong to the EU). The UK prided itself on its system of light regulation, which meant essentially self-regulation, an oxymoron.

The Brussels Effect: How the European Union Rules the World

by

Anu Bradford

Published 14 Sep 2020

Scholars have instead shown that international trade has frequently triggered a “race to the top,” whereby domestic regulations have become more stringent as the global economy has become more integrated.7 Still, the race-to-the-bottom paradigm remains influential, shaping the debates among scholars and policy makers alike. The Brussels Effect adds to this literature by showing how the benefits of uniform production across the global marketplace incentivizes companies to adjust their regulatory standards upward rather than downward. The discussion on global regulatory races mirrors the debates on regulatory outcomes in federal systems. The “Delaware Effect” has been used to explain the race to the bottom in corporate law within the United States: since corporations can incorporate in any state irrespective of where they do business, all states have an incentive to relax their chartering requirements in order to attract corporate tax revenues.

…

Other states then respond by lowering their respective regulatory standards to avoid capital flight.178 The result of this race is, theoretically, regulatory convergence at the bottom. However, subsequent empirical studies have questioned the extent to which a race to the bottom occurs in practice.179 Influential literature has further emerged to argue that economic globalization has instead produced a “race to the top,” where countries are elevating their regulatory standards in response to first mover regulators’ introduction of stringent regulatory standards.180 While empirical support for a global race to the bottom is limited, most would agree that corporate relocation is more likely in instances where the firm can freely select its regulatory jurisdictions (such as stock listing) without any need to physically move its operations to another jurisdiction.181 In such instances, recent research demonstrates an occurrence of “Tiebout sorting” where no race to the top or bottom can be observed, but where firms instead sort themselves across jurisdictions depending on their differential cost structures, heterogeneous preferences, and market segments.182 Some firms are likely to prefer lower regulatory standards, while others, in fact, prefer higher regulatory standards.

…

: Corporate Globalization and the Erosion of Democracy, at ix, xi (1999). 5.See Alan Tonelson, The Race to the Bottom: Why a Worldwide Worker Surplus and Uncontrolled Free Trade Are Sinking American Living Standards 14–15 (2002). For a general discussion of this dynamic, see Dale D. Murphy, The Structure of Regulatory Competition: Corporations and Public Policies in a Global Economy (2004), in particular Parts I, II, and V. 6.See David Vogel & Robert A. Kagan, Introduction to Dynamics of Regulatory Change: How Globalization Affects National Regulatory Policies 4–5 (David Vogel & Robert A. Kagan eds., 2004). 7.See Debora L. Spar & David B. Yoffie, A Race to the Bottom or Governance from the Top?

No Is Not Enough: Resisting Trump’s Shock Politics and Winning the World We Need

by

Naomi Klein

Published 12 Jun 2017

Rather than hope that Trump is going to magically transform into Bernie Sanders, and choose this one arena in which to be a genuine advocate for anyone who isn’t related to him, we would do far better to ask some tough questions about how it’s been possible for a gang of unapologetic plutocrats, with open disdain for democratic norms, to hijack an issue like corporate free trade in the first place. The Race to the Bottom Trump has made trade deals a signature issue for two reasons. The first, on full display that day at the White House, is that it’s a great way to steal votes from the Democrats. The right-wing pundit Charles Krauthammer—no fan of unions—declared on Fox News that Trump’s cozy union summit was a “great act of political larceny.”

…

What Trump’s admiration for Puzder suggests is that his real plan for luring back manufacturing is to suppress rights, wages, and protections to such a degree that working in a factory will be a lot like working at Hardee’s under Andrew Puzder. In other words, it’s yet another plan to take from the vulnerable to benefit the already outrageously rich. What we are witnessing is not a silver lining of any sort. It’s the push to the finish line in the “race to the bottom” that opponents of these corporate trade deals always feared. Yes, It’s Possible to Make Bad Trade Deals Worse Trump is not planning to remove the parts of trade deals that are most damaging to workers—the parts, for instance, that prohibit policies which are designed to favor local, over foreign, production.

…

One area of concern was how these deals were leading to devastating job losses, leaving behind rust belts from Detroit to Buenos Aires, while companies such as Ford and Toyota looked for ever-cheaper places to produce. But for the most part, our opposition was not grounded in Trump-style protectionism; it was trying to stem the beginning of what already looked like a race to the bottom, a new world order that was negatively impacting workers and the environment in every country. We were arguing for a model of trade that would start with the imperative to protect people and the planet. That was crucial then—it’s urgent now. The movement was even starting to win. We defeated the proposed Free Trade Area of the Americas.

Consumed: How Markets Corrupt Children, Infantilize Adults, and Swallow Citizens Whole

by

Benjamin R. Barber

Published 1 Jan 2007

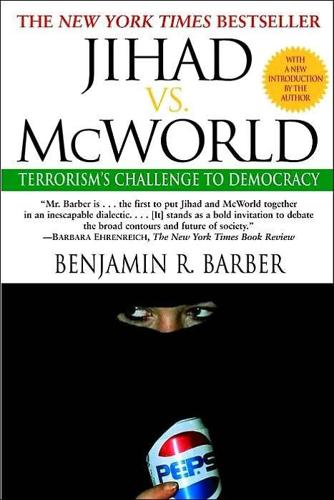

While Johnson does not quite endorse the nutritional merits of cream pies, he must revel in the recent studies suggesting chocolate is good for us (after all), and he obviously grasps what Howard Stern teaches so well: that shock/shlock sells only if it feels subversive and hence progressive. “Where most commentators assume a race to the bottom and a dumbing down—‘an increasingly infantilized society,’ in George Will’s words,” Johnson enthuses, “I see a progressive story: mass culture growing more sophisticated, demanding more cognitive engagement with each passing year.”55 Johnson sets himself squarely against the kind of cultural criticism implied by the idea of an “infantilist” ethos that purportedly spurns nuance and complexity. Consumerism’s “cultural race to the bottom is a myth; we do not live in a fallen state of cheap pleasures that pale beside the intellectual riches of yesterday.

…

The selling of the body, which with the passing of actual slavery became a metaphor for coercive exchanges that were largely invisible (Marx and Foucault), has today become a toxic but remarkably well tolerated exemplar of the subordination of identity to commerce, and includes the selling of the constituent elements of the human genome. Roughly 20 percent of the genome has now been patented for private commercial use, and the trend is accelerating. As with so many other elements in the global race to the bottom, it is globalization that drives privatization: the quest for genetic patents is a function of the globalization of research. If “we” don’t do it, the Koreans or the French or the Chinese will. And since consumables along with the “need” for them must in any case be marketed globally for capitalism in its late consumer phase to flourish, bioengineering, cloning, and other advanced forms of genetic research are bound to be put into corporate hands.

…

For whatever the causes, and in South Africa they may go back to “the failure of the state, both during and after apartheid…to create jobs, health care, housing, and education accessible to the vast majority of the population,” the fact is that “when justice and social-control methods are ceded to the private sector—to private security firms, to vigilante groups, to simple mob justice…democracy becomes an empty promise.”72 Inequality is built into the market system, which too often becomes a race to the top for those who are wealthy, and a race to the bottom for everyone else. Inequality is not incidental to privatization, it is its very premise. The implicit tactic employed by the well off is to leave behind those who get more in public services than they contribute as taxpayers in a residual “public” sector (a kind of self-financing leper colony that cannot self-finance) and throw in with those who have plenty to contribute in their own private “commons.”

Grouped: How Small Groups of Friends Are the Key to Influence on the Social Web

by

Paul Adams

Published 1 Nov 2011

These examples are taken from Jonah Lehrer’s book How We Decide (Houghton Mifflin, 2009). 14. Find out more on Itamar Simonson’s research in the 1993 article “Get closer to your customers by understanding how they make choices.” 9. Marketing and advertising on the social web The problems facing interruption marketing Interruption marketing is a race to the bottom For the past 100 years, marketers have mostly relied on interruption marketing to get their message across, and viewed each new technology as a new way to interrupt people from what they were currently doing to get them to consume their message instead. Our TV programs are interrupted by ads.

…

We are being bombarded by more and more competing information, yet our capacity for processing and remembering this information remains the same. The increased competition for that attention means marketers must increase the frequency of their communication, exacerbating the problem. We’re seeing advertising appear in more and more unusual places. No one owns this problem and so it gets worse and worse.1 Interruption marketing is a race to the bottom. The most common way for marketers to increase their chances of being noticed is to increase the frequency of their campaigns. More people are likely to notice it, but it creates immense volumes of noise. On average, you need to run an ad 27 times before someone remembers it: Only one out of every nine ads is noticed, and people need to see the ad three times to remember it, so it takes 27 impressions for it to sink in.2 People no longer trust marketers One clear trend over the past 50 years is that people are more wary of advertising, and trust businesses less than they used to.3 In fact, this is so prevalent that researcher Dan Ariely has found that mistrust in marketing information negatively colors our entire perception of a product, even when we have direct experience to the contrary.

…

People will increasingly turn to their friends for information The amount of information accessible to us is increasing exponentially, but our capacity for processing ideas and memory will remain the same. In a world of too much information, marketing and advertising based on interrupting people, or trying to shift their attention from something else, is a race to the bottom. In this information rich world that we have created, people will increasingly turn to their friends for advice. Marketing will need to focus activities on gaining permission to market to people by being credible, trustworthy, interesting, and useful, and by marketing to small, connected groups of friends.

Company: A Short History of a Revolutionary Idea

by

John Micklethwait

and

Adrian Wooldridge

Published 4 Mar 2003

In 1830, the Massachusetts state legislature decided that companies did not need to be engaged in public works to be awarded the privilege of limited liability. In 1837, Connecticut went further and allowed firms in most lines of business to become incorporated without special legislative enactment. This competition between the states was arguably the first instance of a phenomenon that would later be dubbed “a race to the bottom,” with local politicians offering greater freedom to companies to keep their business (just as they would much later dangle tax incentives in front of car companies to build factories in their states). All the same, it is worth noting that the states gave away these privileges grudgingly, often ignoring the Dartmouth College ruling and often hedging in “their” companies with restrictions, both financial and social.

…

Virginia turned itself into what one legal treatise called a “snug harbour for roaming and piratical corporations.” The New York legislature was forced to enact a special charter for the General Electric Company to prevent it from absconding to New Jersey. But the big winner of this particular “race to the bottom” would be Delaware. By the time the Great Depression struck, the state had become home to more than a third of the industrial corporations on the New York Stock Exchange: twelve thousand companies claimed legal residence in a single office in downtown Wilmington.21 Most of the other industrial trusts converted to holding companies, too.

…

A persistent theme of this book has been the jostling for power between the company and government. The balance has unquestionably swung in the company’s favor. The modern firm is not in the same position as the East India Company, which had to go cap in hand to parliament every twenty years to renew its charter. Companies have often profited from “races to the bottom” by forcing governments and American states to compete for their favors. They have also encroached on the prerogatives of nation-states and embedded themselves in the body politic: think of the effect of corporate advertising or modern corporate control of the media. Companies have sometimes been able to outfight even the most powerful governments: IBM survived the American government’s biggest antitrust case of the 1970s; Microsoft seems to have thwarted the biggest assault of the 1990s.

People, Power, and Profits: Progressive Capitalism for an Age of Discontent

by

Joseph E. Stiglitz

Published 22 Apr 2019

Thus, American citizens are actually hurt as a result of the higher prices. Even Obama, who prided himself in his efforts to lower the cost of medicine, in the TPP (the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement) betrayed his principles. 11.The race to the bottom takes many other forms: banks, for instance, said that unless regulations were loosened, they would relocate their activities elsewhere. The result was a regulatory race to the bottom. The 2008 global financial crisis was among its consequences. 12.Taxes are only one of many variables that affect where firms locate, as we have already noted. But even focusing just on taxes, lowering taxes will induce firms to relocate if the country from which we are trying to steal jobs doesn’t respond.

…

The tech giants know how to wield their power in many arenas.77 Amazon used the enticement of thousands of jobs to get cities across the country bidding to have it set up its second headquarters in those cities through, for instance, lower taxes—shifting the tax burden onto others, of course. Small firms can’t do this, and so it gives an enormous advantage to Amazon over local retailers. We need a legal framework that prevents these races to the bottom.78 Intellectual property rights and competition There is one area where government sanctions monopolies: when a patent is given, the innovator gets temporary monopoly power. As we move to a knowledge-based economy, intellectual property rights (IPR) are likely to play an increasing role.

…

There are some footloose firms that have actually done this, giving some credibility to the argument.10 Of course, having achieved lower corporate taxes in one country, they turn around to other nations, saying that if they don’t lower their taxes businesses will leave. Not surprisingly, corporations love this race to the bottom.11 The argument that we had to lower corporate tax rates to compete with others was invoked by Republicans as they slashed the corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 21 percent in 2017,12 just as it had been used earlier, in 2001 and 2003, as taxes on capital gains and dividends were cut. The earlier tax cuts didn’t work—they didn’t lead to higher savings, an increase in labor supply, or higher growth,13 and there is no reason to expect that the 2017 cut will either.

The Great Divide: Unequal Societies and What We Can Do About Them

by

Joseph E. Stiglitz

Published 15 Mar 2015

This was important, because it allowed a steady flow of cash into the housing market, which in turn provided the fuel for the housing bubble. The rating agencies’ behavior may have been affected by the perverse incentive of being paid by those that they rated, but I suspect that even without these incentive problems, their models would have been badly flawed. Competition, in this case, had a perverse effect: It caused a race to the bottom—a race to provide ratings that were most favorable to those being rated. Mortgage brokers played a key role: They were less interested in originating good mortgages—after all, they didn’t hold the mortgages for long—than in originating many mortgages. Some of the mortgage brokers were so enthusiastic that they invented new forms of mortgages: The low- or no-documentation loans to which I referred earlier were an invitation to deception, and came to be called liar loans.

…

In this way we could increase investment and employment here at home—a far cry from the current system, in which we in effect encourage even U.S. corporations to produce elsewhere. (Even if U.S. taxes are no higher than the average, there are some tax havens—like Ireland—that are engaged in a race to the bottom, trying to recruit companies to make their country their tax home.) Such a reform would end the corporate stampede toward “inversions,” changing a corporation’s tax home to avoid taxes. Where they claim their home office is would make little difference; only where they actually do business would.

…

American innovations in rent seeking—enriching oneself not by making the size of the economic pie bigger but by manipulating the system to seize a larger slice—have gone global. Asymmetric globalization has also exerted its toll around the globe. Mobile capital has demanded that workers make wage concessions and governments make tax concessions. The result is a race to the bottom. Wages and working conditions are being threatened. Pioneering firms like Apple, whose work relies on enormous advances in science and technology, many of them financed by government, have also shown great dexterity in avoiding taxes. They are willing to take, but not to give back. Inequality and poverty among children are a special moral disgrace.

American Kleptocracy: How the U.S. Created the World's Greatest Money Laundering Scheme in History

by

Casey Michel

Published 23 Nov 2021

Ibid. 5. Ibid. 6. “Standard Oil,” Encyclopedia Brittanica, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Standard-Oil. 7. Davis, “Delaware Inc.” 8. American Law Review 33 (St. Louis: Review Publishing, 1899), 419. 9. “Tax Competition and the Race to the Bottom,” Tax Justice Network, https://www.taxjustice.net/topics/tax-competition-and-the-race-to-the-bottom/. 10. Hamill, “The Story of LLCs: Combining the Best Features of a Flawed Business Tax Structure.” 11. American Law Review 33, 419. 12. Nicholas Shaxson, Treasure Islands (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012). 13. Davis, “Delaware Inc.” 14.

…

And it means that it’s the states that are making millions from corporate registration fees, which they can use to buoy their budgets. With this competition—with states offering increasing efficiency and protections for corporate clients, including those who wanted anonymity—American states engaged in a so-called race to the bottom. And where that bottom lies remains anyone’s guess. 3 CONTROL EVERYTHING, OWN NOTHING “Imagine the possibilities!” —Wyoming Corporate Services1 Most of the audiences S. D. Woo encountered when traveling had never heard of Delaware, or knew anything about the state. Even most Americans would be hard-pressed to rattle off more than a few facts, if any, about the state.

…

The corporate sprint to New Jersey sparked a response from other state governments looking to get their share of this new Klondike gold mine. A renaissance in “business friendly” regulations quickly followed, with regulatory rollbacks racing from state to state. Thanks to these turn-of-the-century innovations, as one researcher related, U.S. states found themselves in that “race to the bottom,”9 with new laws imposing fewer and fewer “restraints on potential corporate abuses.”10 Basic corporate regulations—things like requiring shareholder input, or assuming liability for any malfeasance or accidents—suddenly began disappearing across states. And along the way, requirements for publicly identifying those behind the corporations also disappeared.

The Globalization Paradox: Democracy and the Future of the World Economy

by

Dani Rodrik

Published 23 Dec 2010

Federal Reserve vice chairman, worrying that international outsourcing will cause unprecedented dislocations for the U.S. labor force; Martin Wolf, the Financial Times columnist and one of the most articulate advocates of globalization, expressing his disappointment with the way financial globalization has turned out; and Larry Summers, the Clinton administration’s “Mr. Globalization” and economic adviser to President Barack Obama, musing about the dangers of a race to the bottom in national regulations and the need for international labor standards. While these worries hardly amount to the full frontal attack mounted by the likes of Joseph Stiglitz, the Nobel Prize–winning economist, they still constitute a remarkable shift in the intellectual climate. Moreover, even those who have not lost heart often disagree vehemently about where they would like to see globalization go.

…

Such a transformation would benefit the communities in which these corporations and their affiliates operate. But, as Ruggie explains, there would be additional advantages. Improving large corporations’ social and environmental performance would spur emulation by other, smaller firms. It would alleviate the widespread concern that international competition creates a race to the bottom in labor and environmental standards at the expense of social inclusion at home. And it would allow the private sector to shoulder some of the functions that states are finding increasingly difficult to finance and carry out, as in public health and environmental protection, narrowing the governance gap between international markets and national governments.7 Arguments on behalf of new forms of global governance—whether of the delegation, network, or corporate social responsibility type—raise troubling questions.

…

Our reliance on global governance also muddles our understanding of the rights of nation states to establish and uphold domestic standards and regulations, and the maneuvering room they have for exercising those rights. The worry that this maneuvering room has narrowed too much is the main reason for the widespread concern about the “race to the bottom” in labor standards, corporate taxes, and elsewhere. Ultimately, the quest for global governance leaves us with too little real governance. Our only chance of strengthening the infrastructure of the global economy lies in reinforcing the ability of democratic governments to provide those foundations.

Chavs: The Demonization of the Working Class

by

Owen Jones

Published 14 Jul 2011

Why, the argument went, should private sector workers with comparatively meagre pensions subsidize the generous settlements of the public sector? There was no doubt that there had been a collapse in private sector pension provision. At the beginning of 2012, the Association of Consulting Actuaries warned that nine out of ten private sectordefined benefit schemes were closed to new entrants. But what was being proposed was a race to the bottom; public sector pensions should be dragged down, not private sector pensions dragged up. The majority of public sector workers saw this rhetoric for what it really was: on 30 June 2011, hundreds of thousands of teachers and civil servants went on strike. But with the Government still refusing to make significant concessions, trade union ballots across the public sector delivered overwhelming support for industrial action.

…

'It's a disgrace, I feel as though I've been used,' said one." It is not just agency and temporary workers who suffer because of job insecurity and outrageous terms and conditions. Fellow workers are forced to compete with people who can be hired far more cheaply. Everyone's wages are pushed down as a result. This is the 'race to the bottom' of pay and conditions. It might sound like a throwback to the Victorian era, but this could be the future for millions of workers as businesses exploit economic crisis for their own ends. In a document entitled The Shape of BusinessThe Next Ten Years, the Confederation of British Industry (CBI)-which represents major employers--claimed that the crash was the catalyst for a new era in business.

…

The real reasons for the strike, carefully obscured by the mainstream media, shed light on some of the complexities underlying the workingclass anti-immigration backlash in modem Britain. The Lindsey refinery's employer, IREM, had hired cheap, non-unionized workers from abroad. Not only did this threaten to break the workers' union, italso meant everyone else's wages and conditions would be pushed down in a 'race to the bottom'. 'We've got more in common with people around this world than with the employers who are doing this to us,' said Keith Gibson, one of the leaders of the strike and a member of the Trotskyist Socialist Party. BNP figures who tried to jump on the bandwagon were barred from the picket line. The demands of the strike committee included the unionization of immigrant labour, trade union assistance for immigrant workers and the building of links with construction workers on the continent.

The Global Auction: The Broken Promises of Education, Jobs, and Incomes

by

Phillip Brown

,

Hugh Lauder

and

David Ashton

Published 3 Nov 2010

There is a recognition that low-cost countries are developing their own knowledge workers capable of achieving global standards that were previously assumed to be out of reach by anyone other than Western workers. Thomas Friedman’s account of the “flattening” of the world economy has been widely debated. He sees little reason to worry about America’s middle classes being embroiled in a global race to the bottom because he focused on the race to the top. The knowledge wars are, he believes, forcing Americans to raise their game in the competition for the best and most innovative ideas, leading him to conclude, America, as a whole, will do fine in a flat world with free trade— provided it continues to churn out knowledge workers who are able 22 The Global Auction to produce idea-based goods that can be sold globally and who are able to fill the knowledge jobs that will be created as we not only expand the global economy but connect all the knowledge pools in the world.

…

We were asked to turn off our recording equipment and in hushed voices, the two officials described their growing misgivings about the impact of free trade agreements working against the interests of American workers but to the benefit of American corporations. The consequences of this shift in economic power also led Robert Scott to conclude, “This shift has increased the global ‘race to the bottom’ in wages and environmental quality and closed thousands of U.S. factories, decimating employment in a wide range of communities, states, and entire regions of the United States. U.S. national interests have suffered while U.S. multinationals have enjoyed record profits on their foreign direct investments.” 23 The financial crash highlighted the economic catastrophe resulting from the failure of federal authorities to regulate financial markets, and the global auction highlights the social catastrophe of failing to regulate the relationship among education, jobs, and rewards.

…

This would reduce the risks managers take and enable them to focus more on the development of productive assets rather than inflating share prices or company profits for personal gain. Governments around the world, including the U.S. administration, also need to change the rules of the global auction. This would include new rules for the conduct of corporations and their executives designed to limit the race to the bottom that the reverse auction implies for many college-educated as well as less qualified workers. International labor A New Opportunity 159 standards would have to be reformed, allowing workers to counterbalance the power of global corporations by strengthening their rights to act collectively across national borders.

In Defense of Global Capitalism

by

Johan Norberg

Published 1 Jan 2001

For if the developing countries pay lower wages, do not protect their environment, and have insufferably long working hours, then won’t their cheap output eliminate our higher paying jobs, forcing us to lower our standards and our wages? We will have to keep working harder and longer to keep up. Firms and capital quickly migrate to where the lowest wages and the worst working conditions exist. It will be a ‘‘race to the bottom.’’ The one with the lowest social standard will win and will corner the investments and export revenues. Theoretically this seems a tough case to answer. The only trouble is that it has no foundation in reality. The world has not witnessed a deterioration of working conditions or wages in the past few decades, but precisely the opposite.

…

Each individual can opt out of certain things so as not to feel permanently at the beck and call of others. You don’t have to check your e-mail over the weekend, and there is no law against turning on the answering machine. Big is beautiful In the anti-globalists’ worldview, multinational corporations are leading the race to the bottom. By moving to developing countries and taking advantage of poor people and lax regulations, they are making money hand over fist and forcing other governments to adopt ever less restrictive policies. On this view, tariffs and barriers to foreign investment become a kind of national defense, a protection against a ruthless entrepreneurial power seeking to profiteer at people’s expense.

…

That is a dismal thesis, with the implication that when people obtain better opportunities, resources, and technology, they use them to abuse nature. Does there really have to be a conflict between development and the environment? The notion that there has to be a conflict runs into the same problem as the whole idea of a race to the bottom: it doesn’t tally with reality. There is no exodus of industry to countries with poor environmental standards, and there is no downward pressure on the level of global environmental protection. Instead, the bulk of American and European investments goes to countries with environmental regulations similar to their own.

Free Ride

by

Robert Levine

Published 25 Oct 2011

Media companies that sell products online have to lower prices in order to compete with pirated versions of those same products sold by companies that bear none of the production costs. By making it essentially optional to pay for content, piracy has set the price of digital goods at zero. The result is a race to the bottom, and the inevitable response of media companies has been cuts—first in staff, then in ambition, and finally in quality. This devaluation could also hurt the Internet, since professional media provides much of the value in a broadband subscription. A 2010 study by the Pew Research Center’s Project for Excellence in Journalism found that more than 99 percent of blog links to news stories went to mainstream media outlets like newspapers and networks.15 File-sharing services are filled with copyrighted music.16 Seven of the ten most popular clips in YouTube history are major-label music videos.17 Amid the Internet’s astonishing array of choices, statistics show that most consumers continue to engage with the same kind of culture they did before—only in a way that’s not sustainable for those who make it.

…

In almost every way, it’s the exact opposite of the more efficient Internet, where more content is pirated than purchased and the producers of shows are pressured into giving them away before another company can do it for them. Competition concerns cost and Google search ranking, and the winners are sites like the Huffington Post. If cable worked like the Internet, the result would be a race to the bottom: shows that are free to watch, cheap to make, and easy to forget. The company that represents the greatest threat to television may be Google. In May 2010, the search giant announced Google TV, a platform that brings the Internet to a TV screen. As with Boxee, that means users can easily download video illegally as well as buy it.

…

Since the Internet has global reach, technology executives worry their companies could be subject to the most onerous regulations of any country in which they operate—“a world of Singaporean free speech, American tort law, Russian commercial regulation, and Chinese civil rights,” as Goldsmith and Wu describe it.10 When Judge Gomez issued his Yahoo! decision, online activists worried it set a precedent that would allow any country to impose its laws on the online world. “We now risk a race to the bottom,” said Alan Davidson, an attorney with the Center for Democracy and Technology who has since become the top lobbyist at Google. “The most restrictive rules about Internet content—influenced by any country—could have an impact on people around the world.”11 This is certainly worth worrying about, but it could be seen as a very American view.

Unfinished Business

by

Tamim Bayoumi

The decision to retain national supervision was crucial as it undermined the European banking system in two ways. Competition across national supervisors meant that they increasingly became supporters for their own major banks. This led to the creation of large “national champions” and promoted a supervisory “race to the bottom” as regulators looked to boost the competitive position of their own champions by not being too intrusive. In addition, the fact that in the end almost all entry into other European countries was through subsidiaries meant that the costs of the eventual crisis were bottled up in individual countries.

…

Bank capital is intrinsically risky as owners are the first to lose their money in the case of financial distress. Accordingly, investors demand a higher rate of return on capital compared to safer forms of borrowing such as bonds or deposits. The concern was that competition across supervisors was creating a regulatory “race to the bottom” in which each country tried to make their banks more competitive by diluting the requirements on their expensive capital buffers, leading to inappropriately thin buffers across the board.17 The risk had been underlined by the international repercussions of major bank failures, such as that of Continental Illinois Bank in 1984.

…

The split between centralized bank supervision and national responsibility for bank rescues risks undermining the effectiveness of centralized ECB supervision of Euro area banks. This is because it replaces one set of misaligned incentives with another set. The problem with the pre-crisis system was that national regulators were responsible for both bank supervision and support, creating incentives for a regulatory race to the bottom. The new system generates a new misalignment of incentives since national regulators, who have responsibility for bank support, will generally want to minimize their assessment of banking problems and the associated costs which will put them at odds with the ECB, which is responsible for supervision.

Melting Pot or Civil War?: A Son of Immigrants Makes the Case Against Open Borders

by

Reihan Salam

Published 24 Sep 2018

Further, the publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content. Version_1 To my sisters CONTENTS TITLE PAGE COPYRIGHT DEDICATION Introduction CHAPTER ONE The Unfinished Melting Pot CHAPTER TWO Somebody Else’s Babies CHAPTER THREE Race to the Bottom CHAPTER FOUR Jobs Robots Will Do CHAPTER FIVE It’s a Small World CHAPTER SIX Nation Building Conclusion ACKNOWLEDGMENTS NOTES INDEX ABOUT THE AUTHOR Introduction A few years ago, a cable news producer asked me to appear on his television program to discuss a grisly murder in which, if I recall correctly, a Muslim immigrant had hacked someone to death in the name of Islam.

…