railway mania

description: speculative frenzy in the UK in the 1840s about railways

69 results

Manias, Panics and Crashes: A History of Financial Crises, Sixth Edition

by

Kindleberger, Charles P.

and

Robert Z., Aliber

Published 9 Aug 2011

Contrariwise, the crisis of 1809–10 had ‘two separate causes: a reaction from the speculation in South America; and a loosening and then tightening of the continental blockade’.79 There was a postwar boom in exports to Europe and the United States in 1815–16 that was larger then the amount that could be sold, plus a fall in the price of wheat. Canals and South American government bonds and mines combined in 1825; British exports, cotton, land sales in the United States, and the beginning of the railroad mania contributed to the crisis in the mid-1830s. The crisis of 1847 was caused by the railway mania, the potato blight, a wheat crop failure one year and a bumper crop the next, followed by revolution in Europe. Thus at least two objects of speculation were involved in most of the significant crises. Just as the national markets were connected, so the speculation was connected by the underlying credit conditions.

…

Moderate excesses burn themselves out without damage to the economy although individual investors encounter large losses. One question is whether the euphoria of the economic upswing endangers financial stability only if it involves at least two or more objects of speculation, a bad harvest, say, along with a railroad mania or an orgy of land speculation, or a bubble in real estate and in stocks at the same time. The monetary dimensions of both manias and panics are analyzed in Chapter 4. The occasions when a boom or a panic has been triggered by a monetary event – a re-coinage, a discovery of precious metals, a change in the ratio of the prices of gold and silver under bimetallism, an unexpected success of some flotation of a stock or bond, a sharp reduction in interest rates as a result of a massive debt conversion, or a rapid expansion of the monetary base – are noted.

…

This book is a study in financial history, not economic forecasting. But investors seem not to have learned from experience. 3 Speculative Manias Rationality of markets The word ‘mania’ suggests a loss of a connection with rationality, perhaps mass hysteria. Economic history is replete with canal manias, railroad manias, joint stock company manias, real estate manias and stock price manias – surges in investment in a particular activity. Economic theory assumes that men and women are rational – and hence manias would not occur. There is a disconnect between the observations that manias occur episodically, and the rationality assumption.

Blood, Iron, and Gold: How the Railways Transformed the World

by

Christian Wolmar

Published 1 Mar 2010

Britain’s more advanced industrialized position allowed it to keep ahead of its European counterparts and as a result it was the first nation to exploit fully the boundless potential of this new technology. It would retain that lead for some time, experiencing a series of railway manias, most notably in the early 1840s, the opening years of Queen Victoria’s reign, that would result in the construction of over 7,000 miles of railway within two decades of the opening of the Liverpool & Manchester. While other countries would also undergo such periods of railway mania, the British version was the first and one of the most fruitful. 11 Britain was, too, the first country to experience a railway scandal. George Hudson, who melded together a vast railway empire controlled by the Midland Railway, for a time Britain’s largest railway company, was exposed as a fraudster who cheated investors out of their money.

…

Most losses occurred when promoters, either fraudulent, stupid or simply over-optimistic, obtained huge sums of money for lines that were never completed so that investors lost all their cash. Investors were most vulnerable during the railway manias which raged through different countries at various times and were swept up in the rush simply because everyone else seemed to think it was a good idea. Railway bubbles simply fit into the history of similar scandals from the Dutch tulip mania of 1637 to the recent banking crisis. There’s no shortage of elegantly embellished but completely valueless railway company share certificates still adorning living-room walls, dating from the various railway manias of the nineteenth century. However, it was when governments became involved that unbelievably huge sums could be purloined by corrupt promoters and the world centre for such activity was the United States, where several later scams dwarfed even the dodgy dealings outlined in Chapter 6 during the construction of the first transcontinental.

…

Americans dreamed of far-reaching rail lines that would span rivers, plough through forests and, finally, cross deserts to reach the other side of the continent. Between the opening of the Baltimore & Ohio in 1830 and the end of the century, the United States was buffeted by a series of railroad fevers which saw the mileage increase in fits and starts, reaching 250,000 miles by 1900. The railroad manias of the UK and other European countries were mirrored in the US, but because the country is so vast and its economic regions so diverse they occurred in various states at different times. Britain experienced a mini-mania in the 1830s and a major one in the following decade, while in the US the rush in the early 1830s to promote railroads was brought to a temporary halt by a panic in some states in 1837 but others continued without a pause and, in any case, the whole country soon recovered its momentum by the end of the decade.

The Four Pillars of Investing: Lessons for Building a Winning Portfolio

by

William J. Bernstein

Published 26 Apr 2002

Treasury bills) Blue Ridge Corporation, 148 Bogle, John Common Sense on Mutual Funds, 224 speculative return, 58-59 Vanguard 500 Index Fund, 97-98, 101 vision of inexpensive fund, 213–217 Bond returns future, as predicted by Gordon Equation, 56 historic, vs. other instruments, 20–22, 28–29 inflation-adjusted, 19 and interest rates, historic perspective on, 14–15 prior to twentieth century, 13–16 real returns, discounted dividend model (DDM) expectations for, 68–69 and risk, 13, 26 risk summary, by investment type, 38–39 as short-term, 257, 259 vs. stocks, 154 twentieth century, 16–23 Bonds in asset mix, 257–263, 258, 259, 264 currency changes from gold to paper (1900-2000), 16–19 defined, 20 end-period wealth, 27–28 as long-term credit, 13-15 mutual fund fees, 215–216 in retirement mix, 231–232 retirement withdrawal rates, 235 types of, 259–263 yield and interest rates, 10, 17, 19 “Bottomry loan” in ancient Greece, 7, 69 Brealey, Richard, 174–175 Bridgewater, Duke of, 141 Bridgeway Group, 216, 250 Brinson, Gary, 107, 225 Britain canal building mania, 141–142, 158 GDP and technological diffusion, 132–134 railroad mania, 143-145, 159–160 South Sea Company, 137–141, 158 Brokers, 191–202 Merrill, betrayal of, 193–194 spreads and commissions, 195–202 Brooks, John, 88, 224 Bubble, term used in Times of London, 144 Bubble Act (British Parliament, 1720), 139–140, 159 Bubbles diving engines, 134–135 English canals, 141–142, 158 railroads, 143-145, 158, 159–160 South Sea Company, 137–141, 158 space race, 149–150 (See also Manias) Buffett, Warren, 72, 90–93 Bull market investor attitudes during, 6, 28 and retirement, 231-234, 236 Roaring Twenties, 145–148, 153 young savers, 236–239 Burns, Scott, 221 Burroughs Inc., 151 Business of investing (Pillar 4), 189–226 about, xii–xiii, 297 brokers (See Brokers) media and press coverage, 219–225 mutual funds (See Mutual funds) BusinessWeek, 154–157, 221 Buy-backs, stock, 55, 60 Calculator, financial, 230, 237 California Public Employees Retirement System (CALPERS), 85 Canals, English, as bubble, 141–142, 158 Capital gains, 54–55, 81, 99, 103, 104 Capital Ideas (Bernstein), 225 Capitalization-weighted index, 33, 95, 244, 245, 255 Cash, real returns on, 68 Center for Research in Security Prices (CRSP), 88, 245 Central banks, inflation control, 20 Chamberlain, Lawrence, 157 Chancellor, Edward, 224 Charles Schwab mutual funds, 216 Children, teaching about investments, 274 Chrysler, Walter, 147 Churchill, Winston, 145 Cisco, 57 Clayman, Michelle, 64 Clements, Jonathan, 85, 98, 103, 221–222, 225 Closed-end mutual funds, 203, 217 C.N.A.

…

The only question is whether public attention might not be called to the impending danger, through the public press.” In short, Britain’s most brilliant prime minister did everything but shout “irrational exuberance!” at the top of his lungs in Parliament. The United States underwent its own railway mania in the post-Civil War period. But even taking into account the clocklike regularity of railroad bankruptcy and the Credit Mobilier scandal (in which this construction arm of Union Pacific plundered the parent company, not unlike the recent Enron scandal), things were a bit tamer here than in England.

…

On the other hand, the Federal Reserve’s mishandling of the liquidity crunch brought on by the 1929 crash magnified its effects, resulting in the Great Depression, which scarred the national psyche for decades. The collapse of railroad shares in 1845 was equally catastrophic; a worldwide depression nearly swept away the Bank of England. Only hard money retained its value. The most long-lasting effect of the railway mania is that Britain, to this day, is cursed with a disorganized bramble of a rail network. Even casual visitors cannot help but notice the contrast with France’s more efficient layout, which was first surveyed by military engineers and then let out for private construction bids. Minsky’s criteria for bubbles work just as well in reverse with busts.

The Great Railroad Revolution

by

Christian Wolmar

Published 9 Jun 2014

Ultimately, the Baltimore & Ohio became more important because the railroads in the North developed in a far more sophisticated way than their southern counterparts. In particular, they were prepared to go over state boundaries to provide long-distance services, unlike in the South, where the railroads largely stayed within individual state borders. These two railroads were part of a wider spurt of railroad activity, a mini version of the “railroad manias” that characterized future developments not just in the United States but across the world. In addition to the two longer coal railroads in Pennsylvania, New York State’s first railroad, the Mohawk & Hudson, which provided a shortcut to a circuitous section of the Erie Canal, had been chartered in 1826.

…

In the 1840s only 375 miles of new canal were added to the network, and closures of the economically weak waterways had already begun. Railroads like the Hudson River Railroad, and indeed the Erie, were being laid parallel to existing canals or river routes, and consequently even the steamboats were beginning to feel the pinch. The decade of the 1850s was a period of railroad mania. Whereas New England had benefited from most of the growth in the 1840s, the focus now shifted to the plains of what is now known as the Midwest but was then called the Northwest. The huge size of the territory meant that in the 1850s, Illinois and Ohio vied for the prize of building the most miles of railroad, a contest that the Land of Lincoln shaded with more than 2,600 miles of track—just 300 more than Ohio.

…

British investment ceased during the Civil War, but resumed by the end of the 1860s. And then it all went sour again with the panic of 1873. The author of the standard work on British investment in American railroads, Dorothy Adler, suggests that British capital helped to fuel this succession of American railroad manias: “It is not stretching the facts to draw a parallel between the late 1840s, the late 1860s and the years 1879–81. Each of these periods was characterized by a speculative movement of British capital into American railway shares.”3 She calculates that by the end of the century, British investment in US railroads totaled around £400 million (perhaps worth one hundred times that amount today, £40 billion), around 10 percent of all American railroad capitalization.

Boom and Bust: A Global History of Financial Bubbles

by

William Quinn

and

John D. Turner

Published 5 Aug 2020

In the mid-1840s they did exactly that, granting charters to hundreds of railway companies during what became known as the Railway Mania. The Economist, in 2008, described the Railway Mania as ‘arguably the greatest bubble in history’.3 This is not just modern hyperbole. Charles Mackay, in the third edition of Memoirs of Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds, wrote that the Railway Mania was greater than anything that had preceded it.4 Karl Marx, in Das Kapital, referred to it as the ‘groβen Eisenbahnschwindel’, which literally means the ‘great Railway Mania’.5 58 THE GREAT RAILWAY MANIA Two decades prior to the Great Railway Mania, a new and revolutionary technology was beginning to transform Britain: steam-powered railways.

…

But this would only have been possible if the political calculus of Parliament had been less wed to regional interests and thus better able to create an efficient national rail network, repressing unnecessary competition and duplicate lines. With such an approach, the Railway Mania would never have happened. The Railway Mania democratised speculation. The financial press, which was meant to protect investors and warn them of bubbles, called the Railway Mania far too late to be of any use to the new speculating class. According to its author, the moral of the Glenmutchkin Railway satire was caveat investor. Investors needed to look out for themselves because no one else would. Within a decade of the end of the Railway Mania, any semblance of government regulation of joint-stock companies in the UK was removed when enterprises were granted the freedom to incorporate without needing prior government approval.

…

The market in railway shares brought an unprecedented level of activity to the stock market: unlike most other company shares, the shares of railway companies traded daily during the Railway Mania.47 Indeed, the marketability of railway equity was such that 15 new stock exchanges opened around the country during the Mania to meet the demand from the growing speculator franchise.48 Seven of these new provincial stock exchanges shut down when the Railway Mania came to an end.49 The next side of the bubble triangle is money and credit, without which there is no fuel to feed a bubble. In the case of the Railway Mania, the Bank of England’s discount rate was reduced in September 1844 to 2.5 per cent, an historic low in the 150 years since the Bank had been established.

The World's First Railway System: Enterprise, Competition, and Regulation on the Railway Network in Victorian Britain

by

Mark Casson

Published 14 Jul 2009

The Committee saw the selection problem as a technical issue, to be decided by applying rational principles to documentary evidence, while MPs believed the issue should be resolved by persuasion, involving public debate conducted through hired legal advocates. After the collapse of the Railway Mania in 1846, commentators highlighted the capital losses sustained by shareholders, and the enormous expenditure on legal fees. They denounced Mania schemes as dishonest, whereas, in fact, most of the schemes were honest attempts to meet the commonly agreed requirements of the regions they planned to serve. The term Mania created a misleading impression, suggesting that the schemes were foolish and that investors were stupid. This study suggests that the failings of the Railway Mania were political and cultural rather than purely psychological.

…

It was bad decision-making, rather than Wnancial speculation, that was the most serious problem. The Railway Mania represented a turning point in the history of the UK railway system. It provided an opportunity for politicians to authorize the planning of a national railway system, and to harness private enterprise for its construction. But Parliament was too weak to reconcile conXicting local interests, and the opportunity was lost. MPs were simply not up to the job of choosing between alternative schemes, and in particular alternative routes between major towns, in terms of national interest. The collapse of the Railway Mania caused private misery for many private investors, and Wnancial ruin for some, but the real tragedy lay in the events that led up to the collapse.

…

To allow for the counterfactual network to include a Severn Tunnel would, however, be incompatible with the premises on which the counterfactual has been constructed. The counterfactual represents an integrated system which could, in principle, have been designed at the time of the Railway Mania. Furthermore, because it is smaller than the actual network, it could have been completed more quickly and would therefore have enjoyed a longer economic life. The cost of this approach, however, is that the whole network has to use technology that was available at the time of the Railway Mania, or shortly afterwards, and this does not include tunnelling under a major river. The penalty to network performance incurred by the omission of the Severn Tunnel is much lower than might be expected, however, for a number of reasons.

Cathedrals of Steam: How London’s Great Stations Were Built – and How They Transformed the City

by

Christian Wolmar

Published 5 Nov 2020

As with today, there was the self interest of construction and contracting firms, run by men such as Thomas Brassey and Samuel Peto, who, together with the managers of the major railway companies and the professionals who helped draw up schemes, formed a ‘railway interest’ that established itself during the railway mania of the 1840s. It was mirrored in Parliament by a large group of probably around 100 MPs, many of whom had directorships or substantial shareholdings in railway companies. This was a tight-knit band of powerful men who often worked on schemes together and all moved in the same circles, meeting socially or through shared business interests. After the collapse of the railway mania, fewer private investors were ready to risk their savings on railway ventures. Because of this shortage of capital available from the public, the contractors began to accept payment for their work in the form of shares or bonds, essentially taking the risk from the success of the venture.

…

This was a period of widespread enthusiasm for railways despite the fact that steam locomotives were very much still in the development stage and not yet a realistic proposition as the power source. The successful opening in 1825 of the Stockton & Darlington Railway, a primitive line mainly operated by horses but using some steam locomotives, demonstrated the potential of the technology and helped stimulate the first period of ‘railway mania’ as it became known. Proposals for lines were submitted to Parliament by more than fifty companies that together envisaged the construction of some 3,000 miles of railway lines. Most of these schemes never got past the design stage, but several were the genesis of what became some of the nation’s first railway lines.

…

The company had sought to raise £1m (around £100m in today’s values) but investors were simply unwilling to risk parting with their money on such a radical idea as a lengthy railway running through London, particularly as the technology was in its infancy. The only line that did emerge in this initial period of railway mania in the South-East was the Canterbury & Whitstable, a six-mile largely cable-hauled line that eventually opened in 1830 after numerous early travails and that has rather unfairly mostly been forgotten. Despite being technologically advanced, it proved to be a somewhat unsuccessful little railway.

Fire and Steam: A New History of the Railways in Britain

by

Christian Wolmar

Published 1 Mar 2009

The expression ‘calm before the storm’ does not do justice to the events of the middle of the decade when Parliament was inundated with bills and the whole economy of the country was, it seemed, geared towards constructing more and more railways. While there were previous and subsequent periods of booms in railway promotion, the years 1845–7 are rightly known as the period of the ‘railway mania’ because of their widespread impact and lasting effect. FIVE RAILWAYS EVERYWHERE Like all booms, the railway mania started imperceptibly. By the mid-1840s, investing in the railways had become an attractive proposition once again and schemes for new lines began to be drawn up in every region of the country. The financial climate had changed and there was optimism in the air with an upturn in the economic cycle.

…

The Liverpool & Manchester represented the start of the railway age – just as it marked a significant advance in the technology – and was far grander in scale and conception than any of its predecessors. While work had progressed on the Stockton & Darlington, there had been something of a mini railway mania, the first of several over the next few decades, as various enterprising promoters put forward ideas for schemes to criss-cross Britain. Lines worth a total of £22m (about £1.32bn today),1 an unprecedented amount of capital at the time, including an ambitious scheme for a London–Edinburgh railway, were put forward in 1824–5, though most never got further than a prospectus and a vague scrawl on a map.

…

The railways had begun their long spread across Britain, but it was to be a stuttering process, with times of rapid expansion alternating with periods of little or no construction. FOUR CHANGING BRITAIN By 1843, just thirteen years after the opening of the Liverpool & Manchester, Britain had the makings of a railway network. The year was a notable one because it marked the end of the first phase of construction and the start of a brief hiatus before the railway mania of the second half of the decade began. There was, too, a lull in activity by the promoters. Once again, times were bad, both economically and politically, following a severe depression in trade caused by a series of failed harvests and the terrible Irish potato famine. There were also genuine doubts about whether Britain needed any more railways.

The Long Good Buy: Analysing Cycles in Markets

by

Peter Oppenheimer

Published 3 May 2020

The Journal of Economic History, 69(2), 409–445. 3 George Hudson and the 1840s railway mania. (2012). Yale School of Management Case Studies [online]. Available at https://som.yale.edu/our-approach/teaching-method/case-research-and-development/cases-directory/george-hudson-and-1840s 4 Brookes, M., and Wahhaj, Z. (2000). Is the internet better than electricity? Goldman Sachs Global Economics Paper No. 49. 5 For discussion, see, see Odlyzko, A. (2010). Collective hallucinations and inefficient markets: The British railway mania of the 1840s. SSRN [online]. Available at https://ssrn.com/abstract=1537338 6 https://www.fhs.swiss/eng/statistics.html 7 McNary, D. (2019, Jan. 2). 2018 worldwide box office hits record as Disney dominates.

…

Marketing Science Journal, 37(4), 507–684. 13 See Frehen, R. G. P., Goetzmann, W. N., and Rouwenhorst, K. G. (2013). New evidence on the first financial bubble. Journal of Financial Economics, 108(3), 585–607. 14 Odlyzko, A. (2010). Collective hallucinations and inefficient markets: The British railway mania of the 1840s. SSRN [online]. Available at https://ssrn.com/abstract=1537338 15 Evans, How (not) to invest like Sir Isaac Newton. 16 Lucibello, A. (2014). Panic of 1873. In D. Leab (Ed.), Encyclopedia of American recessions and depressions (pp. 227–276). Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. 17 Browne, E. (2001).

…

Gagnon, J., Raskin, M., Remache, J., and Sack, B. (2011). The financial market effects of the Federal Reserve's large-scale asset purchases. International Journal of Central Banking, 7(1), 3–43. Galbraith, J. K. (1955). The great crash, 1929. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. George Hudson and the 1840s railway mania. (2012). Yale School of Management Case Studies [online]. Available at https://som.yale.edu/our-approach/teaching-method/case-research-and-development/cases-directory/george-hudson-and-1840s Gilchrist, S., and Zakrajsek, E. (2013). The impact of the Federal Reserve's large-scale asset purchase programs on corporate credit risk.

The Price of Time: The Real Story of Interest

by

Edward Chancellor

Published 15 Aug 2022

See Martin Hutchinson, ‘The Bear’s Lair: What Liverpool Could Teach Today’s Fed’, True Blue Will Never Stain, 22 July 2019, www.tbwns.com. 37. Andrew Odlyzko writes that ‘an investigation of Mackay’s newspaper writings shows that he was one of the most ardent cheerleaders for the Railway Mania, the greatest and most destructive of these episodes of extreme investor exuberance’ (‘Charles Mackay’s Own Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Railway Mania’, University of Minnesota, February 2011). 38. Andrew Odlyzko, ‘Collective Hallucinations and Inefficient Markets: The British Railway Mania of the 1840s’, University of Minnesota, January 2010. 39. Grant, Bagehot, p. 32. 40. Ibid., p. 28. 41. Gayer et al., Growth and Fluctuation, I, p. 300.

…

Nurske, Ragnar, International Currency Experience: Lessons of the Inter-war Period (New York, 1944). Odlyzko, Andrew, ‘Bagehot’s Giant Bubble Failure’, Working Paper, University of Minnesota, 29 August 2019. Odlyzko, Andrew, ‘Charles Mackay’s Own Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Railway Mania’, University of Minnesota, February 2011. Odlyzko, Andrew, ‘Collective Hallucinations and Inefficient Markets: The British Railway Mania of the 1840s’, University of Minnesota, January 2010. Okina, Kunio et al., ‘The Asset Price Bubble and Monetary Policy: Japan’s Experience in the Late 1980s and the Lessons,’ Monetary and Economic Studies, February 2001. Olson, Mancur, The Rise and Decline of Nations: Economic Growth, Stagflation, and Social Rigidities (New Haven, Conn., 1982).

…

The speculative frenzy subsided in the summer of 1810, after which around a third of the country banks failed.35 Lord Liverpool later reflected on these events in a speech to the House of Lords: ‘The tendency of an inconvertible paper money is to create fictitious wealth, bubbles, which by their bursting, produce inconvenience.’36 The British railway mania of the 1840s took place while the young Bagehot was reading mathematics at University College London. The whole nation was transfixed by the potential of rail travel and an index of British railway shares more than doubled between 1840 and 1845. Among the speculators was the journalist Charles Mackay, an acquaintance of Charles Dickens and author of Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds – the first popular account of early speculative manias, published in 1841.37 The book’s warnings about the dangers of speculation were lost not only on the British public but also on Mackay himself.

The City on the Thames

by

Simon Jenkins

Published 31 Aug 2020

A local journal reported that, ‘a band of music having taken up position on the roof of the carriage, the official bugler blew the signal for the start and the train steamed off amidst the firing of cannon and the ringing of church bells’. Residents ran to their roofs to watch. Little did they realize the noise, soot and disruption that was soon to descend on their lives. By then the first railway ‘mania’ had seized the reform parliament, with London the centre of attention. Plans were brought forward for lines from Birmingham to the Marylebone boundary at the New Road, and from Southampton to Nine Elms (later extended to Waterloo). In June 1837, as the new queen was taking the throne, Robert Stephenson’s first ‘inter-city’ train from Birmingham emerged from a tunnel through Primrose Hill to Camden Town.

…

By then, London’s nine private water companies were already supplying most of the city with piped and reasonably clean water. Belatedly, London’s most essential item of modern infrastructure was in place. For the most part it is still in working order today. The settling of the railway The railway mania of the 1840s, largely completed in the 1850s, left London with a portfolio of termini – north, south, east and west – in the most unsatisfactory places. It was noticeable that in the west, landlords had proved powerful enough in parliament to fight off intrusion on their estates. Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s Great Western Railway was stopped by the church from moving from Paddington into Bayswater.

…

In 1853 a philanthropic peer, Lord Shaftesbury, demanded that railway companies stipulate the scale of their clearances, and the possible impact they might have on poverty. He could at least deploy shame. But as so often in London’s history, money talked louder than shame, and the railway lobby retorted that for all the misery at least it got things done. Within twenty years of the railway mania, London’s surface rail network was largely completed. It was an astonishing if brutal chapter in London’s history. Going underground London was now ringed by termini, of which those in the north and west were two to three miles from where most of their passengers worked. The City’s surveyor at the time, Charles Pearson, saw this as potentially disastrous for business.

Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital: The Dynamics of Bubbles and Golden Ages

by

Carlota Pérez

Published 1 Jan 2002

A decade after the first industrial revolution opened the world of mechanization in England and led to the rapid extension of the network of roads, bridges, ports and canals to support a growing flow of trade, there was canal mania and, later, canal panic. About 15 years after the Liverpool– 3 4 Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital Manchester rail line inaugurated the Age of Steam and Railroads, there was an amazing investment boom in the stock of companies constructing railways, a veritable ‘railway mania’ which ended in panic and collapse in 1847. After Andrew Carnegie’s Bessemer steel mill in 1875 gave the big-bang for the Age of Steel and heavy engineering, a huge transformation began to change the economy of the whole world, with transcontinental trade and travel, by rail and steamship, accompanied by international telegraph and electricity.

…

But the turbulent nature of this period emerges from its fundamental tensions. The wealth that has grown and concentrated in relatively few hands is greater than can be absorbed by real investment. Much of this excess money is poured into furthering the technological revolution, especially its infrastructure (canal mania, railway mania, Internet mania), often leading to overinvestment that might not fulfill expectations. So at this time there tends to be a sort of gambling economy with asset inflation in the stock market,64 looking like a miraculous multiplication of wealth. Confidence in the brilliance of financial geniuses grows and attempts at regulation are seen as hindering the way to a successful society.65 This new capacity of money to make money attracts more 62. 63. 64. 65.

…

big-bang 1971 1875 Age of Steel, Electricity and Heavy Engineering USA and Germany overtaking Britain 3rd to continent and USA) 1829 1771 IRRUPTION INSTALLATION Five successive surges, recurrent parallel periods and major financial crises Age of Steam and Railways 2nd Britain (spreading 1st GREAT SURGE Figure 7.2 78 Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital Financial Capital and Production Capital 79 The figure shows the truly major collapses located about two or three decades after the big-bang of each revolution. Apart from the relatively regular timing, it is interesting to note that these particular bubbles have tended to bear the name of the infrastructure of the corresponding revolution: canal mania, railway mania and now the Internet bubble, so that in these cases the ‘main objects of speculation,’ as defined in the Kindleberger model,93 happen to be of a technological nature. Other regularities are worth noting: ● ● ● collapses are less likely during Irruption and Synergy,94 though frequent at the passage from the installation to the deployment period and vice versa; there is a bunching of crises in the turbulent economy of the frenzy phase and in the decelerating economy of the maturity phase; and the passage from the early to the late phase of each period is sometimes marked by a financial crisis.

Boom: Bubbles and the End of Stagnation

by

Byrne Hobart

and

Tobias Huber

Published 29 Oct 2024

And, to really bring the example full circle, Alphabet invests some of its immense ad profits in R & D programs—including research into fusion-based power. Spillovers like these, which long outlive the bubble itself, are a defining feature of innovation-accelerating bubbles. Formal futures markets were formed during the 17th-century Dutch tulip bubble. The railway networks that materialized during the British railway mania in the 1840s continue to move passengers and freight. Fiber-optic networks and Amazon survived the dot-com collapse of the early 2000s. Similarly, the Manhattan Project “bubble” burst in the sense that after the bombs detonated the program was wound down with the conclusion of the war, yet the resulting innovations remain critical to the way we live now.

…

Attracted by the prospect of higher returns, more investors follow suit, triggering feedback that fuels further technological development and growth. This is classic bubble behavior. When funding for a new technology is decoupled from rational expectations of economic return, collective risk aversion drops, propelling creativity. This was true for the canal bubble in the 1790s, the railway mania in the 1840s, the electrical utility boom of the 1920s, the proto-tech bubble of the 1960s, and, more recently, the dot-com bubble of the 2000s. It’s also the case with Bitcoin. Creativity can be expressed in several ways, including in the stories we tell ourselves about a new technology’s potential.

…

Or, as the 19th-century writer and historian Thomas Carlyle put it, “Every new opinion, at its starting, is precisely in a minority of one.” 331 But instead of a phase of hallucinatory frenzy that culminates in a temporarily stabilizing sacrifice, it results in a crash—the burst of the bubble—which can be similarly cathartic. It is unsurprising that in the aftermath of almost every failed speculative mania, a scapegoat needs to be sacrificed for the collective sins of exuberance. From railway stock promoters in the British railway mania of the 1840s to Bernie Madoff, Elizabeth Holmes, Sam Bankman-Fried, and other various and sundry crypto scam artists today, the history of bubbles and crashes is littered with the symbolic bodies of investors, speculators, and fraudsters that society needed to sacrifice in order to recover from the destabilizing effects of financial manias.

St Pancras Station

by

Simon Bradley

Published 14 Apr 2007

All looked rosy for the Midland at this point, for its system included part of the only railway route to York and the north, by means of a junction at Rugby with the London and Birmingham’s line to Euston. However, the end of this monopoly was soon in sight: in 1846 the Great Northern Railway was enacted, on a more direct course between York and its new terminus at King’s Cross. The newcomer was one of the more successful promotions of the ‘Railway Mania’ of 1844–7, a classic bubble in which railway shares took on the false lustre of licences to print money and hosts of extravagant and contradictory schemes contended for the capital of the propertied classes. Hudson managed one strategic master-stroke during this heady time by absorbing the new railway from Birmingham to Bristol into the Midland’s system.

…

The mixed metaphors from war, statecraft and biology are telling; the Midland is at once a living organism seeking natural growth and an innocent nation-state subjected to the sinister machinations of a rival power. Conflicts of this kind followed inevitably from the state’s refusal to do much more than impose a modest framework of regulation on the industry. The Railway Mania saw the consequences at their lunatic height: at one point 815 railway ventures were before Parliament, costed at a total of six times the national annual expenditure. It was quite different abroad, where the entire network was sometimes centrally [ 137 ] St Pancras.indb 137 13/9/07 12:12:15 planned from the beginning, as in Belgium.

…

G. 17, 20, 50 jam, manufacture of 152–3 Jerrold, Blanchard 126–7 Jersey City station 79 Jones, Owen 106 K Keats, John 28 Kempthorne, Sampson 30–31 Kew Palace 26 King, Revd Samuel 30 King’s Cross Station 1, 14, 63–6, 68–9, 72, 78, 82–3, 85–6, 88–9, 92, 95, 98, 100, 136, 138, 157–8, 162, 164, 168, 171 Great Northern Hotel 63–6, 95–6, 131 Kipps 143–4 L Ladykillers, The 14 Lansley, Alastair 164 Las Vegas 109 Leeds 98, 125, 137 Leicester 14, 96, 135, 138, 153, 162 Lewis, Joseph 46 Limerick, Earl of 112 Liverpool 149 Cathedral 22 Lime Street Station 63, 74 Liverpool and Manchester Railway 132–4 London: 1860s improvements 8 Agar Town 8–9, 158 Albert Memorial 17, 41, 107 British Library 138, 163 [ 188 ] St Pancras.indb 188 13/9/07 12:12:20 Buckingham Palace Hotel 128 Camberwell 22, 37 Camden Town 83 Crystal Palace 61, 67, 70, 80, 83 Euston Road 1–2, 8, 12, 59, 63 Fleet river 7, 68 Foreign Office 45–7, 54, 86, 159 Grand Hotel, Trafalgar Square 128 Grosvenor Hotel 96, 108 Homerton 30 Hotel Cecil 128 Houses of Parliament 28 Kentish Town 68 Langham Hotel 108, 128 Olympic zone 173 Regent’s Canal 68 Ritz Hotel 128 Royal Courts of Justice 50 Savoy Hotel 108–9, 128 Somers Town 9 Victoria and Albert Museum 111 Westminster Abbey 20–21 Westminster Hall 89 Westminster Palace Hotel 108, 128 Whitechapel 126–7 see also St Pancras Station, St Pancras (churches and churchyards), other railway stations by name London and Birmingham Railway 60, 135 London and Continental Railways 96, 163 London and Greenwich Railway 68 London and North Western Railway 74, 135–7 London Bridge Station 68 London, Brighton and South Coast Railway 96 London, Chatham and Dover Railway 69, 97 London, Midland and Scottish Railway 61, 129, 146 M Manchester 56, 97, 120, 137, 161 Manchester Central Station/G-MEX 79 [ 189 ] St Pancras.indb 189 13/9/07 12:12:20 Manchester and Leeds Railway 143 Manhattan Loft Corporation 163, 168 Maré, Eric de 158 Margarot, Maurice 9 Marriott Hotels 163, 170 Marylebone Station 96, 139, 145 Melton Mowbray 150–51 Metropolitan Railway 2, 8, 69 Midland Grand Hotel see St Pancras Station Midland Railway 6, 22, 46, 54–5, 58, 61, 67, 69, 73, 81, 92, 96, 98, 100, 104, 112, 119–20, 128, 133–40, 151, 154, 161 London extension 6, 54, 69, 96–7, 134–8 milk, supply of 149–50 Modernism 34, 46, 84–5 Moffatt, William Bonythorn 31 Morris, William 53–4, 56–8 N Nairn, Ian 76, 102 Nash, Paul 129–30 New York, Grand Central Station 79, 81, 83, 145 Newcastle upon Tyne, Central Station 91–3 Newington church (Kent) 173 Newman, John Henry 172 O Ordish, Rowland Mason 67 Otis, Elisha 108 Oxford 23, 37, 41 P Paddington Station 1, 65–6, 88, 91, 96 Great Western Hotel 66, 128, 131 Palmerston, Lord 45 Paris 14, 26, 79, 138, 151, 162 Eiffel Tower 80 Galérie des Machines 79–80 Gare du Nord 83 Paxton, Joseph 61 Peabody, George 126 Pendleton, John 154 Pennsylvania Railroad 79 Pevsner, (Sir) Nikolaus 46, 86, 158 Poor Law rooms 30–31 [ 190 ] St Pancras.indb 190 13/9/07 12:12:20 Roberts, Henry 30 Rohe, Mies van der 84 Roman de la Rose 113 Royal Academy (London) 20 Royal Institute of British Architects 20, 129 Rugby 135–6 Ruskin, John 40, 46, 53, 54–6, 58, 84, 173 Seven Lamps of Architecture 40, 53, 56 pork pies, manufacture of 150–51 Portland, 5th Duke of 143 printing industry 148–9 Private Eye 11 Pugin, Augustus Welby Northmore 28, 32–6, 44, 53, 56, 83–4, 91 Contrasts 30–31 True Principles of Pointed or Christian Architecture, The 34 Pullman carriages 144 Punch 127 S Q Quarterly Review 57, 83, 87 Queen Anne style 51–2 R Rail Link Engineering 164 Railway Magazine 125 Railway Mania (1840s) 135, 137 Reading Gaol 31, 112 Red House 53–4 RHWL (architects) 168 Richard III (film) 14 Richard Griffiths Architects 170 Richards, J. M. 85 St Pancras (saint) 1, 4–5 St Pancras (churches and churchyard) 1, 5–6, 9, 14–15, 26–7, 69, 166, 173 St Pancras Station 1–4, 8–10, 14–16, 28, 38–9, 41–50, 58, 65, 82, 86–8, 92, 96–8, 132, 134, 138–40, 144, 155–72, 174 booking hall 42, 104, 160, 170 conversion, 2004–7 4, 10, 162–8 conversion proposals, 1960s–90s 160–63 goods depots and yards 136, 138, 150, 161–3, 171 [ 191 ] St Pancras.indb 191 13/9/07 12:12:21 Midland Grand Hotel 2–4, 10–14, 17, 22, 38–9, 42–50, 54, 59, 61, 77–8, 82–3, 95–6, 98–131, 142, 144, 157–64, 168–71; bathrooms, 118–9; Billiard Room, 114; closure (1935), 10, 127– 31; conversion, 2006 onwards, 4, 168–70; Coffee Room, 113–14; dining room, 114; entrance hall 106–7, 170; guests’ rooms 116–18; Hairdressing Room, 114; Ladies’ Coffee/Smoking Room, 114–15, 129; lavatories, 115; lifts, 108–9; Smoking Room, 114; service rooms, 122–3; staff dormitories, 124–5; staircase 42, 102, 109–14 restoration, 1990s 163 threatened redundancy, 1960s 157–60 train shed 59, 66–82, 98–9, 104, 106, 116, 127, 139, 157, 161, 164–8 Underground station 121, 162, 166–8 Sang, Frederick 116 Schopenhauer, Friedrich 40 Scott, (Sir) George Gilbert 4, 15–22, 27–31, 36–42, 44–50, 52, 54, 56–7, 67, 76–7, 80, 83, 86, 94, 98– 100, 104, 110–11, 120–21, 159–60, 170, 172 Personal and Professional Recollections 22, 29, 36–7, 41, 46, 77 Remarks on Secular and Domestic Architecture 38–9, 44, 83, 111 Scott, George Gilbert, junior 9, 22, 50 Scott, Sir Giles Gilbert 22 Scott, Sir Walter 28 Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings 56 Shaw, Norman 50 sickle-truss roofs 73–6 Simmons, Jack 8 Skidmore, Messrs 111 Smith, P.

Running Money

by

Andy Kessler

Published 4 Jun 2007

You could put in a 20-mile railroad for the equivalent of $650,000 and collect that much in fees every year, because it was cheaper than horses, a lot cheaper. Joint-stock companies became the rage, and the stock market was all too happy to step in and provide capital. Then more capital. And then too much capital. By the 1840s, a railroad mania was raging, stocks selling on multiples of passenger miles, a precursor for multiples of page views that Yahoo stock would trade on 150 years later. An inven- B&W IPO 93 tor named Charles Babbage complained that “the railroad mania withdrew from other pursuits the most intellectual and skilful draftsmen” and sought to invent a machine that might replace them, and make Yahoo possible. Charles Dickens marveled at railroad wealth.

…

Investors made money, investors lost money, but in the best and worst of times, the railroads got built, and people and goods were shuffled about more and more cheaply. The Industrial Revolution hit its stride. Railroad mania hit the U.S. after the Civil War. It gave the New York Stock Exchange something to trade besides government debt. Railroads helped create the pools of capital that funded innovation in the U.S. for the next century. Man, I’d like to short horse stocks right here. Railroads look interesting, especially since they need some government mandate for the right of way between two destinations. Put up $650 grand to make that much in fees each year—no wonder there was a railroad mania. Gotta make sure to jump off this one when ticket and hauling prices start to crack.

How We Got Here: A Slightly Irreverent History of Technology and Markets

by

Andy Kessler

Published 13 Jun 2005

Joint stock companies were the rage, and the stock market was all too happy to step in and provide capital. And more capital. And then too much capital. TRANSPORTATION ELASTICITY 49 By the 1840’s, a “Railroad Mania” was raging, with stocks selling on multiples of passenger miles, a precursor for multiples of page views that Yahoo stock would trade on 150 years later. An inventor named Charles Babbage complained that “the railroad mania withdrew from other pursuits the most intellectual and skilful draftsmen.” He sought to invent a machine that might replace them, and although he couldn’t have foreseen it, make Yahoo possible.

…

A few small-scale models were demonstrated, but the engine was ahead of its time, by probably 100 years. After 10 years of trying, he gave up. He brooded around for a while and then in 1837 announced a somewhat less ambitious plan, the Analytic Engine, which would do math faster and to a larger scale than a Pascaline. Babbage complained that a Railroad Mania, then raging, hired away all the skilled workers and his Computing Engines were, at least partially, an attempt to do without them. The daughter of poet Lord Byron, the lovely Augusta Ada King, Countess of Lovelace, was his assistant. This was key in getting government funding. Again, a few models were demonstrated, but like his Difference Engine, the Babbage Analytic Engine never actually worked.

The Trains Now Departed: Sixteen Excursions Into the Lost Delights of Britain's Railways

by

Michael Williams

Published 6 May 2015

So no dream this – the name lives on today in maps and bus timetables, even though the last train departed nearly half a century ago. A clue as to how this surreal rural outpost of the world’s first urban railway could ever have come into existence lies in the blind and almost suicidal panic with which new railways were promoted in the railway mania of the middle of the nineteenth century. Like every economic bubble since, investors scrambled to put their money into rival schemes vying often to connect the same places no matter how economically or socially viable they might be. It was a boom in which the reputations and fortunes of promoters were either transformed beyond dreams or cruelly shattered.

…

Journeying by train from Leeds City station today, it is hard to imagine anyone battling to lay claim to this drab railway hinterland through post-industrial West Yorkshire, yet so vicious was the rivalry between the North Midland Railway and the Great Northern Railway to get their trains to the promised land of Leeds in the 1840s that it led to the notorious Methley Junction Incident – one of the nastiest episodes in the railway mania that gripped Britain at the time. When the GNR refused to yield to the Midland’s demand not to build its own line to Leeds, the Midland threatened unsuccessfully to stop its trains and levy a toll on every passenger. On the eve of the opening GNR officials, suspicious that the Midland might be up to something dastardly, sent a light engine along the track and found the points had been removed at Methley, a junction just outside the city.

…

Minus the ebb and flow of passengers, the arrival and departure of trains, they are little more than mausolea. The fire and steam that forged them has been doused, leaving them as dead things, devoid of spirit. In mitigation it may be argued that some were victims of a necessary rationalisation, redundant products of that nineteenth-century railway mania during which rival companies insanely vied to block each other’s moves on the railway chessboard. In Britain as a whole, because of the intense rivalry of the train companies, only four major cities – Newcastle, Aberdeen, Stoke-on-Trent and Carlisle – managed to amalgamate their railway traffic into a single station.

Great Continental Railway Journeys

by

Michael Portillo

Published 21 Oct 2015

The presence of the British was not always appreciated by a German populace being stirred by a new-found nationalism. However, there were benefits too. Thomas Worsdell (1788–1862) established a manufacturing base in Germany during a four-year spell as locomotive, carriage and wagon superintendent for the Leipzig railway. A form of railway mania soon infected all the German states, eager to reap the benefits. Keen to have its own prestigious network, the Prussian government guaranteed the investments of those who put money into railway construction. As investors had nothing to lose, funds flowed freely into the German railroads. This rapid expansion meant home-grown talents were fostered and highly valued.

…

The charismatic Napoleon, whose era came next in French history, was equally egalitarian in his approach. Working people everywhere saw hope for a better future. The royals and the aristocracy, by contrast, were horrified. The freedoms that had been fought for in France were dearly held and there was genuine concern that the ideals of the revolution should not be lost in a flurry of railway mania. Sometimes it happened, usually on the most popular routes. Those people using the train to get to the South of France were unconcerned about who was profiting when they bought their tickets. If they hadn’t seen some of the great paintings of the region, they almost certainly had seen glamorous posters which cropped up at stations and in hotels.

…

Still that hesitancy is reflected too in the length of time that the people of Barcelona had to wait for the construction of the city’s metro, even after official agreement had been given. These delays may well have worked in Spain’s favour. French investors were looking for fertile new ground after their domestic system approached capacity. Eventually, it attracted English money as the railway mania bubble burst in Britain in the 1840s, leaving speculators looking outside the UK, where the profitable aspects of the railway network were already in place, to countries like Spain. Sadly, much of the good work was undone in the Spanish Civil War in the 1930s, and it would take years to bring the system back to a high mark.

Lying for Money: How Fraud Makes the World Go Round

by

Daniel Davies

Published 14 Jul 2018

Because it was the early 1980s and the Reagan Revolution was beginning to find its form, the solution to the S&Ls’ problems had to involve deregulation. The idea that the main problem of finance is excessive red tape and that all problems can be solved by leaving things to the market has been a constant since the Victorian Railway Mania. And so, successive rounds of deregulation took place. The first one removed size limits on S&Ls, in the hope that they would be able to ‘grow out of trouble’. Immediately, a wave of mergers began. This had the short-term effect of improving things. Because of an accounting quirk – not itself dishonest, but open to abuse – merging an insolvent S&L with a borderline-solvent one tended to make the accounts look better.* To finance this growth, they were allowed to borrow from sources other than small depositors, including the junk bond market.

…

Looking back at the era, it is strange to see that repeated episodes not just of frauds, but of waves of exactly similar frauds, took a very long time to result in any measures from the authorities, and that the ‘market discipline’ which ought to have driven out bad operators and created a demand for professional auditing and verifiable accounts, didn’t work. A clue as to why this might have been the case can be gleaned from some of the names given to the fraud waves; there was the Railway Mania, the Finance Company Mania, the Mining Mania and so on. There was, in fact, huge wealth and value being created by mobilising the savings of the British middle class to finance productive industry. And this was the priority of Victorian England. Fraudsters and crooked bankers are stock characters in Dickens, Trollope and Thackeray, and it has been estimated that as much as one-sixth of the stock market flotations between 1866 and 1883 were frauds.

…

A. 201–3,205 Henry VIII 216 high-net worth investors tendency to have time on hands 109 tax strategies of a proportion of 266–8 Hippocratic Oath 134 hire purchase scam (Leslie Payne) 36, 39–40 homomorphism 209, 212 Hooley, Ernest ‘The Millionaire’ 230 hotel bills 37 House of Commons 1 Howe, Sarah 90, 116–19, 222 HSBC 188, 189, 280 Hudson Oil 249, 251 Humphery, John Stanley 228 I IBM 64–8 Iceland 218–22 Inca Empire 226–7 Incentives 13, 22, 62, 74, 115, 135, 159, 165, 174, 185–6, 205, 210 incidental fraud vs entrepreneurial 213, 215, 287, 288 Infinity Game 92–9 information 24, 71, 199–208, 211–15, 238 control of by fraudsters 41, 65, 71, 115, 173 insider, securities fraud 23, 239–42, 260 inheritance 117, 217, 218–22, 235, 266 insider dealing 23, 106, 129, 241–43, 260 insurance 36, 39–40, 65, 163–4, 171, 225, 228 medical 74–7, 84 Payment Protection Insurance (PPI) 187–97 insurance scam (Leslie Payne) 40–41 International Reply Coupons see Ponzi, Charles investors 1, 16 in OPM leases 65–7, 69–71 Charles Ponzi’s 86–9 hedge fund 96, 104–9, 113 in pigeons 100, 103 institutional 104 nineteenth century female 118–20 mining 126–30 reliance on accounts 142–54 expectations of UK banks 188 Victorian 228, 231 Retail 240–43 in Piggly Wiggly 256–61 IRS vs UBS 263–4 Israel, Sam see Bayou Capital drug habit of as potential indicator something was wrong 116 J Jehoash (high priest) 217 John Bull 230 K Keating Five 182 Keating, Charles 177–83, 214 Kennedy, John Fitzgerald 61 Kerviel, Jerome 165 King, Don 163 Knights of Industry 234, 237 Kolnische Volkszeitung 232, 234, 236, 237 KPMG 150 Kray, Ronnie and Reggie 26–7, 31, 36, 39, 41 Kutz Method 152–3 KYC (know your customer) 281 L Lab fraud anaemia 74 Ladies’ Deposit Bank (Boston) 116–19 lawyers 19, 27, 33–4, 39, 45, 71, 115, 117, 161, 180, 182, 194, 196, 225, 267, 271, 272, 281 (they’re usually in the background even when not specifically mentioned) professional qualifications of 114 extreme expensiveness of 234 leasing tax advantages of 64 see also OPM Leasing importance of residual value 66 accountancy issues 152 Leeson, Nick 17, 165–73, 285 Lehman Brothers collapse 13 relationship with OPM Leasing 65, 71 Lehnert, Lothar 235–7 Lernout & Hauspie 150 Let’s Gowex see Gowex letterhead 31, 70, 80, 122 Levi, Michael 81, 216, 283 Levy, Jonathan 224 libel 77, 236–8 LIBOR 1–4, 12–16, 193, 205, 215, 244 Liman & Co 235–6 limited liability 34, 225, 231 Lincoln Savings & Loan 177–8, 180, 182–3 livestock 100 Livingstone, Jesse 259 Lloyd’s of London 164, 225 Lomuscio, Joe 59 Long firms 21, 23, 27, 29, 35, 41–2, 43–50, 61, 63, 72, 73–5, 77, 79–82, 96, 141, 142, 163, 164, 212, 224, 283, 284 ‘sledge-drivers’ 232–4 against government 271–4 Lucifer’s Banker 263 M MacGregor, Gregor 5, 8, 9, 17, 77, 78, 214 dubious knighthood of 7, 162 military career 7 previous frauds 18 Madden, Steve 147 Madoff, Bernard 96, 104–5, 113 Mafia 41, 253 Mahler, Russ 249–53 management scientific 19, 200, 206–12, 215 risk management 212–13, 287 strategic 248 public sector 264 marginal cost pricing 248 Marino, Dan (fraudster) 107–9, 113, 115 Marino, Dan (quarterback) 107 maritime capitalism 34, 224–6 market corner 259 market crimes 23, 24, 58, 194, 239–62, 271, 282, 289 markets general characteristics of 23, 197, 201–4, 208, 278, 289 financial 3, 4, 8, 13, 26, 58–60, 99, 100, 107–8, 129, 132, 142–5, 147–8, 149, 150–56, 161, 163, 166, 171–2, 176, 195, 230–31, 239–40, 242–4, 256–61 pharmaceutical, ‘grey’ 136–7 drugs, illegal 43–50 prime bank securities 110–11, 184 real estate 179–80 supermarkets 213, 255 Marx, Groucho 66 Marx, Karl 84, 232, 247 McGregor, Ewan 165, 173 McVitie, Jack ‘The Hat’ 26, 41 Medicare 73–6,134–5, 199, 289 Merchant of Venice 34 Merck Pharmaceuticals 138–40 Michaela, Maria 215, 222 military planning 204, 207, 211 Milken, Michael 177, 183 Miller, Norman 52 mis-selling 194–6 money laundering 278–82 Monopolies Commission (UK) 247 mortgages 38, 77, 101, 175–9, 188, 191, 194, 215, 238 multi-level marketing 94–5 N New England Journal of Medicine 139 New Zealand 9, 172, 241 newspapers 9, 125, 152, 230, 237, 252, 262 Nichols, Robert Booth 110–12 Nikkei index 170–71, 173 nobility Scottish 7 phony scottish 5–9, see Gregor MacGregor phony 223 North Wales Railway Company 229 notaries 114, 125, 133 indiscriminate stamping of documents by in 1920s Portugal 121–2 O ODL Securities 112–13 OECD 268 oil recycling 249–54 OODA loop 208 operations research 204, 208–10, 289 OPM Leasing 63–72 snowball effect of interest expense 98 accounting trick 152–3 options markets 163–4, 171–2 Optitz, Gustav 235–7 Opus Dei 53, 57 Original Dinner Party 92 Other People’s Money 63, 285 P Paddington Buys A Share 20, 43 Parmalat 155 Patsies see fronts Payment Protection Insurance (PPI) 187–97 Payne, Leslie 26–8, 30, 33–6, 39–42, 67, 73, 98, 163, 237, 283 petrol stations 190, 247–8 pharmaceutical industry 133–41 track and trace 136 Philadelphia Savings Fund 70–71 Pigeon King International see Galbraith, Arlan pigeons, racing 100–103 Piggly Wiggly 255–61 Ponzi, Charles 84–90, 96, 109, 116 trial of 90 takeover of Hanover Trust 88–9 launch of scheme 86 Portuguese Banknote Affair 120–25 Powers, Austin 263 Poyais 5–9, 15, 78, 121, 162, 215, 219, 287, 297 prime bank securities 110–13, 122, 184 Prince 135 Prince Albert 228 Princess Caraboo see Baker, Mary Princesses 6, 223 Principles of Scientific Management 206 Prison 18, 61, 112, 119, 125, 173, 208, 252, 270 debtor’s 34, 225 private equity 144 psychology 17, 87 public choice theory 210–11 pump and dump 147 pyramid schemes 91–5, 116, 184, 222 Q Quakers 118 quality control 184, 207, 213–15, 287 Quanta Resources 251–2 Quarterly Review 162 Queen Victoria 228 Queenan, Joe 10 Qwest 150 R Rabelais, Francois 120 Railway Mania 176, 231 Ranbaxy Laboratories 137 Reagan, Ronald 174–5, 251 real estate 89, 177–81, 214, 281 Reddit 48 regulators financial 2, 4, 14, 18, 99, 165, 177–83, 194–5, 240, 260–61, 280–81, 289 softness of in 1960s London 40 environmental 250–51 pharmaceutical 136, 137, 140 Reuschel, Rollo (Stanislaus Reu) 232–8 libel case 237 Richmond-Fairfield 107 Robb, George 228 Rockwell Industries 66–71 Rogers, Will 283 rogue traders 98, 165–73, 215 Royal Canadian Mounted Police 129 S salting (mining fraud technique) 127 Sarbanes-Oxley 194, 202 Saunders, Clarence 255–61 Savings and Loans 174–84, 185, 196, 285, 289 economic theories of failure 174 business model 175 settlement, securities 60, 107, 108, 112, 163, 257, 261 Sherman Antitrust Act 246 shipowners 10, 116, 117, 164, 224–6 ships 164, 207, 221, 224–6 US Navy 89, 249 short firm 73–5, 93 short selling 147, 258–9, 261, 283 shotgun/rifle technique 76–7, 134 signatures, forged 67, 123 Silk Road (online market) 44, 47–8, 50 simplified summary which hopefully captures the important structural features see homomorphism Sketch of the Mosquito Shore 8, 162 Skilling, Jeff 17, 142, 153 slaves 34, 219–21, 225 ‘sledge-drivers’ 232–8 SLK Securities 108, 115 Smith, Adam 11, 213 on cartels 246 snowball effect see compound interest societies, high and low trust 10, 16, 62, 125, 166–7, 264, 287 Soviet planning 204, 208, 227 Sparrow, Malcolm 74, 76 St Joseph (fictitious city) 5 stock exchanges Alberta 11, 129 Toronto 129 Vancouver 11, 126 London 9, 117 New York 59–60,147, 228–31, 256–61 Chicago 59–60, 256 Singapore 170–72 Osaka 170 Tokyo in general 142–5, 147, 163–4,241–2 NASDAQ 240 Strangeways, Thomas 162, see also Gregor MacGregor Strathclyde Genetics see Galbraith, Arlan Stratton Oakmont 145–8 Sufficient Variety, Law of 209 Sullivan, Scott 154 Susquehanna River 251, 252 T tacit knowledge 202–3 Tarantino, Quentin 105 tax 32, 64, 69, 98, 155, 159, 177, 191, 263–71 value added see VAT Taylor, F.

On the Wrong Line: How Ideology and Incompetence Wrecked Britain's Railways

by

Christian Wolmar

Published 29 May 2005

Agriculture prospered because of the better links between town and country which allowed farmers to get most of their products, from fruit and milk to chickens and cattle, to markets more quickly and cheaply; areas of the country which could not be reached easily before were suddenly opened up; labour became much more mobile; tourism became possible; and even the fish and chip shop owes its existence to the faster transit of fish inland.⁵ The growing importance of the railways ensured that the government was forced to react in 1844 when the infamous ‘railway mania’ began threatening the finances not only of existing railways but of many hapless investors in new railway schemes. With the main lines already largely mapped out, the railway mania saw an explosion of speculative and ill-conceived railway projects. Between 1844 and 1847, plans were laid before Parliament that, cumulatively, would have created 20,000 miles of new railways, many in direct competition with one another.

…

Nevertheless, the construction of the railways could, arguably, be considered the finest achievement of the Victorians, a success all the more remarkable because, while the development of the whole network took some seventy-five years, the core of today’s system was already in place by the end of the first ‘railway mania’ in 1852. By then there were 6,600 miles of railway route open compared with just 100 in 1830.¹ It was inevitable that even Victorian governments, with their laissez-faire ethos, should become involved in what rapidly became the country’s largest industry and one which had all kinds of social, political and economic ramifications.

…

In many European countries there was an additional factor, in that railways, which for the first time allowed the rapid mobilisation and movement of armies, were considered a vital strategic asset and the military took a close interest in their development. But in free-enterprise Britain, government meddling, whatever the motive, was anathema while developers continued to believe that great fortunes could be made out of the railways. In the event, however, the lines built in the wake of the railway mania, with a few exceptions, turned out to be mildly profitable at best or, in the case of most rural services, uneconomic from the outset. Gladstone’s Act did also introduce a key measure, the Parliamentary Train, which greatly widened the market for railway travel, which had hitherto been confined to the relatively affluent.

The Railways: Nation, Network and People

by

Simon Bradley

Published 23 Sep 2015

For the Railway Times, it was quite good enough that Scotland could be reached after 1840 by fast steamship from the new rail-connected port at Fleetwood, Lancashire (‘What more can any reasonable man want?’). But the picture changed again as the high dividends on railway shares were noted – so much so that the mid 1840s were remembered for the ‘Railway Mania’. This was a textbook boom in which stock was oversubscribed and prices were inflated by speculators who got in early in order to sell up at an immediate profit; hence Karl Marx’s description of the phenomenon in Kapital as ‘the first great railway swindle’. Everything then came down with a crash, so that more than a third of the railway mileage authorised in these years was never built.

…

Railway companies themselves added considerably to this acreage of newsprint. Established lines placed regular notices concerning services and traffic, especially small ‘non-display’ advertisements in local papers. New ventures burnt through piles of money in self-advertisement, and for the associated legal notices. This kind of outlay peaked early with the Railway Mania of the mid 1840s. For a time during 1845, the Morning Post came with a supplement devoted entirely to railway matters. In three months of the same year, the Direct London, Holyhead & Porth Dinllaen Railway, a representative Mania project, spent £1,255 18s 8d on self-promotion in the press and still came to nothing.

…

The board of the little St Andrews Railway in Fife, opened in 1852 with Thomas Bouch as engineer, were dismayed to discover a few years later that the economical Bouch had built bridges from scanty untreated timbers and made the interval between the sleepers a foot wider than specified in the contract. Huish’s basic point may seem obvious enough, but many companies in the 1830s and 1840s had done nothing to safeguard their futures in this way, preferring to dish out their surpluses in big dividends instead. One contributory cause of the Railway Mania was the mirage of permanent enrichment from railway shares which these payments helped to induce. Another creature of the Mania years was George Hudson (1800–71), one of those plausible rogues who rise to the surface of financial bubbles. Hudson used an inherited fortune to build a municipal power base at York, from which he secured election as chairman of the York & North Midland Railway in 1836.

Company: A Short History of a Revolutionary Idea

by

John Micklethwait

and

Adrian Wooldridge

Published 4 Mar 2003

By 1840, two thousand miles of track, the bare bones of a national network, had been built—all by chartered joint-stock companies. Acts of Parliament were required for every line: there were five a year from 1827 to 1836, when the number jumped to twenty-nine. In the same year, parliament, trying to stop the growing “railway mania,” limited loans to one-third of the chartered railways’ capital, and it also banned any borrowing until half their share capital had been paid up. In the 1844 Railway Act, the state reserved the right to buy back any line that had operated for twenty-one years—a right that came in surprisingly useful during the nationalization mania a century later.

…

“We will venture to assert,” decided an 1835 circular to London bankers, “that taking into account all the railways north of Manchester not one twentieth part of the capital was provided by members of the stock exchange.”19 But the importance of tradable equities increased, particularly once the railways started issuing preference shares, which provided a guaranteed dividend rate (making their value easier to work out for investors), yet counted as equity under the government’s debt-to-equity rules: by 1849, they accounted for two-thirds of the railways’ share capital.20 Most of these shares were traded on local exchanges, such as Lancaster—out of reach of Lombard Street, which was still more interested in public debt than private equity. Railway mania was fanned by a growing number of railway papers, such as the Railway Express, Railway Globe, and Railway Standard. In its first issue in 1843, the Economist devoted less than a tenth of its “commercial markets” column to money-market and stock prices. It bitterly condemned the railway speculation, forecasting a “universal domestic affliction.”

The Currency Cold War: Cash and Cryptography, Hash Rates and Hegemony

by

David G. W. Birch

Published 14 Apr 2020

He goes on to observe that the ‘power of the current narrative is that it brings together so many features which make for an attractive and infectious story’, which I think is in keeping with some observers’ view of Bitcoin as a protest movement rather than a financial revolution. I have a suspicion that Kay might be wrong, though. I think Bitcoin will have an impact and that it will lead to the creation of new markets. His mention of the railways reminded me that the cryptocurrency mania of today has mimetic echoes of the railway mania that arose after the Industrial Revolution and peaked in the mid-nineteenth century. I wrote about this back in December 2011 for Financial World and made the point that Victorian Britain’s railway boom was truly colossal. The first railway service in the world started running between Liverpool and Manchester in 1830, and less than two decades later (by 1849), the London and North Western Railway had become the Apple of its day: one of the biggest companies on the planet.

…

Bitcoin: a peer-to-peer electronic cash system. White Paper, Bitcoin.org, 31 October. Ng, E. 2019. Iran leader urges deeper Muslim links to fight US ‘hegemony’. Associated Press, 19 December. NIST. 2016. Quantum-safe cryptography. Report, National Cyber Security Centre, 30 November. Odlyzko, A. 2011. The collapse of the railway mania, the development of capital markets, and Robert Lucas Nash, a forgotten pioneer of accounting and financial analysis. Accounting History Review 21(3), 309–345. Orcutt, M. 2020. An elegy for cash: the technology we might never replace. MIT Technology Review, 3 January. Paolo, M. 2019. A brief explainer of mini-BOTS, Italy’s parallel currency.

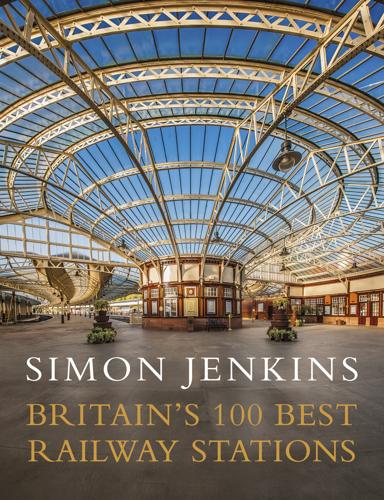

Britain's 100 Best Railway Stations

by

Simon Jenkins

Published 28 Jul 2017

A Victorian historian, John Francis, recorded that ‘the most cautious of men … heard the cry at every dinner, uttered by solemn, solid men, upon the glories of the rail; they read of princes mounting tenders, of peers as provisional committeemen, of marquesses trundling wheelbarrows and of privy councillors cutting turf on correct geometrical principles. Their clerks left them to become railway jobbers. Their domestic servants studied railway journals. They saw the whole world railway mad.’ The period became known as the Mania, by which I refer to it throughout this book. Railway mania: John Bull drunkenly accepts proposals for investing in railways, cartoon, 1836 In November 1845, The Times calculated that parliament had that year projected 1,200 new railways in Britain, notionally requiring £500m in public subscription (or £50bn today). Some were for lines along parallel routes, some for trains running the length and breadth of the land.

…

To study Huddersfield’s Palladianism, Battle’s monasticism or Great Malvern’s naturalism is to wonder at the variety of messages the new industry was seeking to convey. As we have seen, few designers of these stations were noted architects. They were engineers who had emerged from the chaos and opportunities of the early railway Mania. Their imagination was derivative and vernacular. We can almost imagine that, in matters of design, the rail industry, especially in its early years, felt constrained by some innate conservatism, by a desire to be thought not too radical, let alone dangerous. For commercial reasons explained earlier, British stations came nowhere near to the scale and grandiloquence of the great continental termini.

On the Slow Train Again

by

Michael Williams

Published 7 Apr 2011

No longer do slow trains clatter into the platform at Snettisham, Fakenham and Potter Heigham. The days when it was possible to buy a day return from Whitwell & Reepham to Hindolveston or Melton Constable, or an arthritic porter incanted the names of little stations from Martham (for Rollesby) to Paston & Knapton, are fast fading from memory. Such was the speed of the railway mania of the nineteenth century (and the social change that was swept along with it) that within fifty years of the opening of the Stockton and Darlington Railway in the heart of the industrial north, almost nobody even in rural East Anglia was more than five miles from a railway station. The problem was that there was no central strategy and no planning.

…

What happened to the lines around Morecambe in the mid-1960s was either Beeching’s worst bungle or a masterstroke, a deliberately engineered and Machiavellian plan to drive away passengers from this beautiful railway. Not so far-fetched – this was a standard tactic of the Beeching-era 1960s. The Little North Western Line, called Little to distinguish it from the bigger and grander London and North Western Railway trunk route from Euston, was promoted in the railway mania of 1845. The idea was to build a main-line route from the Midlands and West Riding to Carlisle and Scotland. There were to be two main branches: one would run from Leeds to Ingleton in the Yorkshire Dales, connecting to the Euston– Glasgow main line at Low Gill; the other was to be a direct line over the Pennines to Lancaster and Morecambe.

On the Slow Train: Twelve Great British Railway Journeys

by

Michael Williams

Published 1 Apr 2010

Hundreds died in the six and and a half years it took to construct the ‘Long Drag’ across the great wilderness of northern England. Many perished from accidents, cold and disease in the unforgiving terrain. Some simply hanged themselves in despair as floods and storms swept away their handiwork. This was truly the Götterdämmerung of the railways. Ironically, this – possibly the craziest – enterprise of the Victorian railway mania need not have been built at all. Back in 1869, when the Settle and Carlisle was begun, there were two perfectly good main lines to take passengers to Scotland – the London and North Western route from Euston via Crewe, and the Great Northern route from King’s Cross via York. But back amid the mahogany and crystal of the Midland Railway’s boardroom in Derby, James Allport, the company’s general manager, was restless.

…

There’s a congested network and you have to get it right, otherwise you end up with a lot of unhappy people. Today we’re having a very nice run and we’re on time, despite running in with an intensive suburban service.’ With his Brunel-like sideburns, you can imagine Bunker back in the mid-nineteenth-century days of railway mania. There is a gleam in his eye as he tells me, As far as the other train operators are concerned, it’s best that we’re invisible. They tolerate us because the running of steam trains like this is enshrined in European legislation. Whether you love or hate steam, they have to accept us – so long as we’re safe and pay our bills.

The Future of Technology

by

Tom Standage

Published 31 Aug 2005

From the industrial revolution to the railway age, through the era of electrification, the advent of mass production and finally to the information age, the same pattern keeps repeating itself. An exciting, vibrant phase of innovation and financial speculation is followed by a crash; then begins a longer, more stately period during which the technology is widely deployed. Consider the railway mania of the 19th century, the dotcom technology of its day. Despite the boom and bust, railways subsequently proved to be a genuinely important technology and are still in use today – though they are not any longer regarded as technology by most people, but as merely a normal part of daily life. Having just emerged from its own boom and bust, the informationtechnology industry is at the beginning of its long deployment phase.

…

Meanwhile, the industry’s relationship with government is becoming closer. All this suggests that the technology industry has already gone greyish at the temples since the bubble popped, and is likely to turn greyer still. Sooner or later the sector will enter its “golden age”, just as the railways did. When Britain’s railway mania collapsed in 1847, railroad shares plunged by 85%, and hundreds of businesses went belly-up. But train traffic in Britain levelled off only briefly, and in the following two decades grew by 400%. So are the it industry’s best days yet to come? There are still plenty of opportunities, but if the example of the railways is anything to go by, most it firms will have to make do with a smaller piece of the pie.

…

And small radio chips called rfid tags will make it possible to track everything and anything, promising to make supply chains much more efficient. But even a new killer application is unlikely to bring back the good old times. “After a crash, much of the glamour of the new technology is gone,” writes Brian Arthur, an economist at the Santa Fe Institute. The years after the British railway mania, for instance, were “years of build-out rather than novelty, years of confidence and steady growth, years of orderliness.” This kind of “new normal”, in the words of Accenture, another it consultancy, may be hard to swallow for a sector that has always prided itself on being different. But for its customers, a more mature it industry is a very good thing: just as the best technology is invisible, the best it industry is one that has completely melted into the mainstream.

Are Trams Socialist?: Why Britain Has No Transport Policy

by

Christian Wolmar

Published 19 May 2016

Numerous early passengers testified to the excitement of going faster than had previously been possible – the speed of a galloping horse was the fastest that anyone had travelled to this point. Fears of being unable to breathe at such speeds or of being killed by an exploding boiler (a more realistic concern but still a relatively rare occurrence) soon abated and a remarkable period of railway growth ensued. The railway mania of the 1840s resulted in the creation of a network of more than 5,000 miles just two decades after the opening of the Liverpool and Manchester – around half of today’s remaining mileage. Passengers flocked to use the trains. The Great Exhibition of 1851, for example, was an astonishing success, attracting more than six million visitors (a third of the population of England and Wales at the time) from all around the country to London thanks to the railways.

Capitalism: Money, Morals and Markets

by

John Plender

Published 27 Jul 2015

Yet his methods were crooked. In 1848 he was found to have bribed MPs, manipulated share prices and defrauded his creditors, resulting in his imprisonment in York Castle for debt. Among the indignities he felt most acutely was hearing that his wax effigy at Madame Tussauds had been melted down. In the railway mania of the time, Hudson was far from being the only fraudster. The requirement to obtain parliamentary consent for the building of railways meant that there was a constant temptation to bribe MPs, while the increasing ease with which companies could be set up and floated was an encouragement to play fast and loose with other people’s money.

…