refrigerator car

description: a refrigerated railway car, traditionally used to transport perishable goods

56 results

Consider the Fork: A History of How We Cook and Eat

by

Bee Wilson

Published 14 Sep 2012

Fish, too, began to travel the country, and in 1857, fresh meat went from New York to the western states. Refrigerated “beef cars” created a new meatpacking industry, centered in Chicago. This was a very American phenomenon: by 1910, there were 85,000 refrigerated cars in the United States, compared to just 1,085 in Europe (mostly in Russia). Fresh meat no longer had to be slaughtered and used immediately. “Dressed beef” could be cooled, stored, and shipped anywhere. The new refrigerated cars had fierce critics, as do all new food technologies. Local butchers and slaughterhouses objected to the loss of business and lamented Chicago’s growing monopoly on meat (and judging from the horrific conditions in Chicago meatpacking factories described in Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle, they may have had a point).

…

A combination of vast cold-storage warehouses and refrigerated railroad cars opened up entirely new food markets. The meat, dairy, and fresh produce industries were the biggest winners. By the time of World War II, Americans were known around the world for their seemingly inordinate appetite for meat and milk (supplemented with glasses of freshly squeezed orange juice and green salads). This appetite—and the means of satisfying it—was largely a creation of nineteenth-century refrigeration. In 1851, butter was first transported in refrigerated railroad cars from New York City to Boston. Fish, too, began to travel the country, and in 1857, fresh meat went from New York to the western states.

…

Local butchers and slaughterhouses objected to the loss of business and lamented Chicago’s growing monopoly on meat (and judging from the horrific conditions in Chicago meatpacking factories described in Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle, they may have had a point). More generally, the population at large was scared of the very thing that made refrigeration so useful: its ability to extend the storage time of food. Alongside the growth in refrigerated cars was a huge growth in cold-storage warehouses. By 1915, 100 million tons of butter in America were in cold storage. Critics argued that “delayed storage” could not be good for the food, reducing its palatability and nutritional value. Another persistent worry was that cold storage was a scam: by delaying the sale of produce, the sellers could push prices up.

The Rise and Fall of American Growth: The U.S. Standard of Living Since the Civil War (The Princeton Economic History of the Western World)

by

Robert J. Gordon

Published 12 Jan 2016

Steady supply by railroads reduced the volatility of prices previously caused by frozen rivers and slow horse transportation, and this in turn reduced the cost of goods and increased their variety. The quality and variety of food began to improve with the invention, in the 1880s, of the refrigerated railroad car. These early cars were not cooled mechanically but had slots for blocks of ice, which made possible the widespread distribution of fresh fruit and vegetables from California and refrigerated fresh-cut meat from the Midwest. The refrigerated car made the beef industry much more efficient and eliminated the death marches in which herds of cattle had been driven on the hoof to large cities. Food quality and variety improved decade by decade, and contamination declined in tandem.

…

A common complaint was “spring sickness” resulting from a lack of green vegetables over the winter. Vegetable gardens were almost universal in this medium-sized city, in which almost everyone, even the working class, lived in single-family structures. A major change between the 1890s and 1920s was the increasing availability of fresh vegetables in the winter as a result of refrigerated railroad cars and in-home iceboxes. Just as in Muncie, in most medium-sized cities and towns, the population lived in single-family dwellings and usually had access to garden plots to grow their own vegetables. It is possible that the USDA data displayed in table 3–2 misses a substantial portion of the increase in urban consumption of vegetables made possible by these garden plots.

…

In a term used by Gary Becker and co-authors, “full income” refers to both market-based income produced per year and the monetary equivalent of changes in the number of years over which that income can be enjoyed.121 The monetary valuation of increased life expectancy should not be viewed, contrary to Nordhaus’s suggestion, as a measure of the output of the health care industry.122 As we have seen, the “health care industry” contributed little to the epochal decline in mortality between 1890 and 1950. Most of the credit is allocated above to developments outside that industry, including the arrival of clean running water and sanitary sewer pipes, reduction in food contamination and adulteration achieved by everything from refrigerated railroad cars to food and drug regulation, and the development of the Pasteur germ theory with its subsequent emphasis on controlling insects, achieving cleanliness, and changing attitudes about the breastfeeding of infants. The estimation of the monetary value of an additional life-year made possible by decreased mortality has been developed most recently by William Nordhaus in one study and by Kevin Murphy and Robert Topel in another.

Nature's Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West

by

William Cronon

Published 2 Nov 2009

Cutting ice near Milwaukee. The ice that cooled Chicago’s breweries and packing plants, and that allowed dressed beef to travel in refrigerated railroad cars, came to the city from ever greater distances. Here ice is being cut on a Wisconsin lake and moved into an immense insulated warehouse for use over the course of the next year. Courtesy Milwaukee Public Museum. Interior view of a loaded refrigerator car. During the 1870s and 1880s, Chicago packers perfected the refrigerated railroad car as a way of transporting meat hundreds of miles without it spoiling. In the process, they drove local wholesale butchers out of business and revolutionized the American diet and food distribution system.

…

The solution that Swift’s engineer finally used to assure uniform cooling was to put boxes filled with ice and brine at both ends of the car, venting them so that a current of chilled air constantly flowed past the meat.99 First introduced by Swift in the late 1870s, this improved refrigerator car was soon in use by all major firms in the dressed beef trade. In addition to Swift, these included Hammond, Nelson Morris, and Swift’s most important competitor, Philip Armour.100 The refrigerated railroad car, like the grain elevator, was a simple piece of technology with extraordinarily far-reaching implications. The most obvious was the steep growth in Chicago beef packing that began in the mid-1870s.

…

Chilling beef in Chicago was easy enough, given the infrastructure already devoted to the ice trade for pork packing. The problem was how to keep meat cold once it began its eastbound journey. The earliest solution was that of George H. Hammond, a Detroit packer who in about 1868 used a special refrigerated railroad car—an icebox on wheels originally designed for fruit shipments—to send sixteen thousand pounds of beef to Boston. The new invention had problems but was enough of a success that Hammond decided to commit himself more fully to the trade. Toward that end, he decided to move nearer to the main source of supply for cattle, and so shifted his operations to Chicago.

Innovation and Its Enemies

by

Calestous Juma

Published 20 Mar 2017

A certain amount of heat was created during the mixing of ice and salt that created a liquid, and its latent heat was removed from the mixture itself, resulting in a colder temperature. This discovery was applied to natural ice cooling, including those involving refrigerators, cold-storage houses, and refrigerated railroad cars. The concept of proper air circulation was also important in the development of this industry. Improvements in natural ice preservation advanced processing and shipping in the food industry. As demand for a diversified diet including unsalted meats and fresh produce grew, however, it became clear that more efficient refrigeration was necessary.

…

If necessary, the meat would be frozen later. This applied to meat byproducts as well. A multistep processing system helped meatpackers keep up with market fluctuation. Air conditioning was developed, which regulated humidity in storage, therefore preventing both dehydration and mold. The industry depended heavily on the refrigerated railroad car, which led to the creation of monopolies as large Midwestern concerns took control of all steps of the refrigeration from slaughter to shipment. Later, the industry would begin to decentralize as refrigerated motor trucks came on the scene. With the new methods of processing and plastic-packaging the meat, smaller packer concerns became as efficient as larger ones.

…

Meanwhile, fruit and vegetable production skyrocketed during the early part of the twentieth century. Body icing was a major innovation in the shipping of produce. In 1930, a crusher-slinger was developed that would deposit snowlike crushed ice on all parts of a refrigerator car using a flexible hose. The USDA initiated a relentless series of product-specific tests to determine the optimal shipping conditions for individual kinds of fruits and vegetables. Regional specialization in produce prevailed. Refrigerated car technology generally improved during this decade. In the case of produce, precooling began to take place in the cars—fans were installed in individual cars to circulate air over the produce until the natural force of air circulation (resulting from the high speeds of the train) took force.

The Taste of Empire: How Britain's Quest for Food Shaped the Modern World

by

Lizzie Collingham

Published 2 Oct 2017

Gustavus Swift, a partner in a Boston wholesale meat business, thought that it would also make more sense on this journey to transport the cattle as meat. However, having invested in stockyards and livestock wagons, the American rail companies were unwilling to reinvest in refrigerated railroad cars. In 1880, Swift turned to the Canadian Grand Trunk rail line, as its northern route was too cold for live cattle. He built refrigerated facilities at the railheads in Chicago and Boston, as well as a fleet of refrigerated rail cars. Chicago now became a centre for huge slaughterhouses cum meat-packing factories, handling thousands of animals each day.27 The more traffic on the rail lines, the more cost-effective this mode of transport became, and by the end of the 1880s, freight rates had fallen by 90 per cent.28 In 1881, America shipped 106 million lb of dressed beef to Britain.29 One in four joints of meat on British dinner tables now came from abroad; in the 1860s, it would have been one in twelve.30 Industrial-scale American meat processing had solved the problem of Britain’s meat supply.

Capitalism in America: A History

by

Adrian Wooldridge

and

Alan Greenspan

Published 15 Oct 2018

They sped past gutters, slicers, splitters, skinners, sawyers, and trimmers at such a speed that Sarah Bernhardt described the spectacle as “horrible and magnificent.”31 It was during a visit to one of these abattoirs that Henry Ford got the idea of the mass assembly line. Gustavus Franklin Swift made another breakthrough with the introduction of refrigerated railroad cars in 1877. Before Swift, cattle had been driven long distances to railroad shipping points and then transported live in railroad cars. Swift realized that he could save a lot of money if he slaughtered the cattle in the Midwest and transported them in refrigerated railway cars to the East.

…

Even by the standards of the time Swift was an enthusiastic practitioner of vertical integration: he even owned the rights to harvest ice in the Great Lakes and the icehouses along the railway tracks that replenished the ice. He quickly built a huge empire—by 1881, he owned nearly two hundred refrigerated cars and shipped something on the order of three thousand carcasses a week—and a highly fragmented industry consolidated into a handful of companies (Swift as well as Armour, Morris, and Hammond). Americans also got much better at food preservation, with the onward march of preserving, canning, pickling, and packaging.

…

Farmer’s Loan & Trust Company, 159 pollution, 168–69, 427, 429 Pomperipossa effect, 440 Pony Express, 19–20, 49–50 Poor, Henry Varnum, 138 population growth, 11, 40–41, 95, 300 populism, 25, 69, 172–73, 245–46, 297, 344, 415 “post-industrial society,” 360–61 Post Office, U.S., 154, 199–200, 251 post–World War II economic expansion, 270–72, 273–98 potholes vs. progress, 394–98 Potter, David, 295 Pratt, Francis, 72 presidential passivity, 157–59 Prince, Charles, 382 prison labor, 87–88 Procter & Gamble, 118–19, 263, 288, 391 productivity, 12–13, 122, 195, 269, 290–93, 453–54 sources of, 14–21 productivity growth, 4, 273–75, 301, 301, 387, 387, 403 Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization (PATCO), 327–28 professional managers, 207–9 Progressive Era, 25, 165, 176–79, 182, 188, 189, 240–41, 251 Prohibition, 192, 197, 263 property rights, 8, 159–60 protectionism, 7, 194, 230–31, 232, 343–44 Protestant Reformation, 7, 69 Protestant work ethic, 44 Public Broadcasting Act of 1967, 303 Public Works Administration (PWA), 244 Pujo, Arsène, 185 Pullman Company, 144 Pullman Strike of 1894, 154, 173 Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, 182–83 Puritans, 7, 60 “pursuit of happiness,” 8 pursuit of self-interest, 6–7 Quaker Oats, 92, 320 Quakers, 60 quants, 381–82 racism, 89, 295 radio, 202–4, 316 Radio Corporation of America (RCA), 203–4, 316, 320 “railroaded,” 172 railroads, 53–55, 96–98, 112–15, 121, 136–38, 139, 166–67, 197–98, 265 first refrigerated cars, 119 first transcontinental, 16, 18, 90, 114 miles of railroad built, 96–97, 97 Rand, Ayn, 277–78 Rand, Remington, 350–51 Random House, 320 Ransom, Roger, 85 Raskob, John, 221, 222–23 ratio analysis, 340 Ratzel, Friedrich, 88–89 Raytheon, 283, 349 Reagan, Ronald, 26, 248, 324, 325, 326–31, 344, 391, 406 Reaganomics, 330–31 regulations, 255–58, 328–29, 411–15, 412, 416, 425 resource constraints, 10–11 resource revolution, 48–49 retirement age, 404, 441, 442–43 Revolutionary War, 5–6, 31, 34–35, 38–40, 62, 69, 266, 266 Revson, Charles, 264–65 Riesman, David, 295, 296 Riggio, Leonard, 341 “Rip Van Winkle” (Irving), 40 risk management paradigm, 383–84 Road to Serfdom, The (Hayek), 26, 277 robber barons, 124–33, 167–68, 170–71, 356 Roberts, George, 341 Rockefeller, John D., 17, 103, 124, 125–26, 128–30, 136, 142–43, 164, 167–68, 187, 190 Rockefeller University, 126 Rockoff, Hugh, 186, 187 Roebuck, Alvah, 141–42 Rogers, Will, 239, 243 Roosevelt, Franklin D., 234–35, 237, 239–62 fireside chats, 204, 240, 243, 252 New Deal, 25–26, 225–26, 242–62, 415 wartime renaissance, 266, 268–70 Roosevelt, Theodore, 110, 124, 153, 179, 181–85, 268, 427 “Rosie the Riveter,” 363 rubber, 47, 110, 198–99 Rubin, Robert, 332 Rumsfeld, Donald, 306, 368 russet potato, 118 Rust Belt, 321–23, 366 Sanders, Harland, 197, 443 San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge, 90 Santa Clara County v.

Appetite for America: Fred Harvey and the Business of Civilizing the Wild West--One Meal at a Time

by

Stephen Fried

Published 23 Mar 2010

“Fred Harvey is a gentleman, boys,” he declared, brushing himself off. “I say, let’s have those drinks.” When the drinks were done, they were served a midnight breakfast as well—the breakfast for which Fred Harvey was becoming famous. The freshest eggs and steak available in the country, shipped directly from farms in refrigerated train cars. Pan-size wheat cakes stacked six high. Quartered wedges of hot apple pie. And cup after cup of the best damn coffee these cowboys had ever tasted in their lives. Red John and his men never made trouble at the Montezuma again. But they still wanted to know, as did more and more people across the country: Who the hell is Fred Harvey?

…

Local residents had a love/hate relationship with the railroads, and Fred’s restaurants, so visible a symbol of what the trains brought to town, were often the targets of local frustrations. Competing restaurant owners resented Fred because they knew he got better, fresher ingredients than they did—and paid less for them, because the railroad waived his freight charges. There were often break-ins at the eating houses or the parked refrigerator cars: not for cash, but to steal those gorgeous aged steaks. Some customers also resented the dress code Fred was instituting in his eating houses: While almost any outfit was allowed in the lunchrooms, men had to wear jackets (which were provided if they didn’t have one) in order to eat in the main dining rooms.

…

Yet Fred did not want this centralized system to quash creativity and ambition, so he encouraged the chefs and managers at the eating houses to be innovative as well as entrepreneurial. If they heard about a good deal on local fruit, vegetables, meat, or fowl, they were encouraged to buy not only for their eating house but for all the others. The fresh ingredients would be loaded into the next Santa Fe refrigerator car—in a compartment that only fellow Harvey chefs could open with a special key—and were sent on down the line. Besides keeping the menus lively, this also led to some of the first wide-scale migration of regional American ingredients and preparations, for which the eating houses became known along with more traditional Continental and British fare.

Cold: Adventures in the World's Frozen Places

by

Bill Streever

Published 21 Jul 2009

By 1880, refrigeration was cheaper than natural ice. With efficient refrigeration, food could be shipped to markets. Hog production grew. Over a few years, beef exports from the United States to the British Isles grew from a hundred thousand pounds a year to seventy-two million pounds a year. More than a hundred thousand refrigerated railroad cars appeared almost overnight. Suddenly, midwestern farmers could undercut New England farmers on dairy products. Refrigeration increased the profitability of ranching, and ranches expanded, implicating refrigeration in the last phase of the eviction of Native Americans from their ancestral lands and the near extinction of the buffalo.

The Pineapple: King of Fruits

by

Francesca Beauman

Published 22 Feb 2011

It indeed made its way as far as Richmond.56 As soon as the war was over, newspapers again began to feature advertisements placed by local grocers for pineapples.57 The period saw a dramatic increase in the demand for all kinds of tropical commodities, in part due to a rise in the national incomes of the leading industrialised states of the continent. The improved transport technology of the post-bellum period, on land as well as at sea, made it possible to indulge this clamour: as early as 1868, refrigerated railroad cars were being used to transport peaches from the Midwest to the east coast, after which the practice became more and more common in the attempt to preserve fresh foods.58 As in Britain, pineapples were now sold in such quantities that the American middle class was able to get in on the act: in 1874, 4,937,125 pineapples were sent to New York from the Bahamas (of which 30 per cent perished on the way).59 Unlike the home-grown pineapple, the imported pineapple tended actually to be consumed.

Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism

by

Anne Case

and

Angus Deaton

Published 17 Mar 2020

One way is to get help from politicians; ideas and competition were enough in act 1, but political protection becomes useful and sometimes even necessary in act 2.3 In the first Gilded Age, Standard Oil bought up competitors and set railroad rates that forced others out of business. The meat-packing industry was founded by Gustavus Swift, who figured out how to use refrigerated railroad cars and a system of ice suppliers to bring cheap fresh meat to eastern cities. Later, the industry turned on its competitors using cartels and price-fixing agreements.4 Private and social incentives were no longer aligned, and businesses got rich on the backs of consumers. Public benefactors turned into “robber barons,” men such as Andrew Carnegie, Andrew Mellon, Henry Clay Frick, John D.

The Dawn of Innovation: The First American Industrial Revolution

by

Charles R. Morris

Published 1 Jan 2012

At first, the cattle had to be driven to train connections in Abilene for delivery eastward to local slaughterers. Within about twenty years, thickening train connections in cattle country consigned the romance of the cattle drive to the pages of dime novels. Shipping dressed meat was obviously cheaper than shipping steers, but the distances required refrigerated railroad cars. Various experiments with ice-packed cars were unsatisfactory until Gustavus Swift, a Massachusetts butcher, added a forced-air circulatory system. But he was stonewalled by the railroads, which had invested heavily in new fleets of cattle cars and expensive stockyards and watering sites.

Frostbite: How Refrigeration Changed Our Food, Our Planet, and Ourselves

by

Nicola Twilley

Published 24 Jun 2024

He bought up the rights to ice from lakes across Wisconsin and southern Ontario and built a chain of icing stations alongside the tracks to top up the railcars every couple of hundred miles. It was a massive investment—and it worked. By 1880, the Swift refrigerator car and the Swift method of slaughtering and packing beef in Chicago were an indisputable success. “The savings through dressing beef in Chicago instead of shipping live cattle east constituted so large a sum per head that Swift beef […] could be sold below the market and still leave a handsome margin,” gloated Louis. “From the time he had his refrigerator car lines going, he was the largest slaughterer of beef.” Where Swift led, his competitors followed, and the amount of beef being shipped from Chicago skyrocketed over the next decade, growing from little more than a rounding error in the late 1870s to surpass the total tonnage of live animals—half of which was inedible hoof, hide, and bone—by the late 1880s.

…

Although he was losing more money than he could afford, Swift seemed undaunted. “ ‘The trouble is, we don’t quite know how to do it right,’ he would admit with not a trace of discouragement,” Louis wrote. “ ‘We’ll get it, though. We’ll learn.’ ” After years of effort and long days spent watching the thermometer, Swift solved the carcass-chilling problem only to confront yet another challenge: the railway companies wouldn’t build his refrigerator cars, and they wouldn’t take his business even if he built them himself. They already owned cars designed to ship live animals, which brought them double the tonnage. Unsurprisingly, Swift’s scheme, which promised to halve their revenue and undercut their existing infrastructural investment, didn’t appeal.

…

She conducted experiments on such topics as the rate of decomposition in drawn versus uneviscerated poultry and the biochemical reason chickens turned a disconcertingly intense shade of green when held at fifty-five degrees.[*6] She also traveled thousands of miles to put together a detailed survey of the nation’s railcar icing stations and to record the temperatures of three sample chickens from each car at regular intervals. Newspaper reports at the time claimed Dr. Pennington rode in the refrigerator car alongside the poultry while making these observations; in fact, she was quick to tell journalists, she rode “in comfort,” in a specially outfitted caboose with a built-in laboratory. “That’s the way to travel, leisurely jogging along, talking over the crops with the farmers at the crossings, switched into a train yard at night,” she reminisced.

How We Got to Now: Six Innovations That Made the Modern World

by

Steven Johnson

Published 28 Sep 2014

A few began transporting beef back east in open-air railcars during winter, relying on the ambient temperature to keep the steaks cold. In 1878, Gustavus Franklin Swift hired an engineer to build an advanced refrigerator car, designed from the ground up to transport beef to the eastern seaboard year round. Ice was placed in bins above the meat; at stops along the route, workers could swap in new blocks of ice from above, without disturbing the meat below. “It was this application of elementary physics,” Miller writes, “that transformed the ancient trade of beef slaughtering from a local to an international business, for refrigerator cars led naturally to refrigerator ships, which carried Chicago beef to four continents.”

…

A., 184 Martin, Grady, 115, 116 Martin, Richard, 96 Martinique, 49–52, 54, 55 Marxism, 40 Materialism, 40 Mauna Kea, 37–40, 39 McDonald’s, 228 McGuire, Michael J., 144 McLuhan, Marshall, 20 Meatpacking industry, 58–59 freezing and, 74 refrigeration and, 65 Medici family, 37 Megacities, 83, 129, 154, 156 Melville, Herman, 202 Memphis, 110 Meninas, Las (Velázquez), 32, 33, 34 Menlo Park, Edison’s lab at, 100, 206, 210–11 Metric system, 217 Metropolitan Opera (New York), 107 Michigan, 180 Microchips, 42, 80, 158–60, 185 Micrographia (Hooke), 22–23, 24 Microns, 158 Microphones, 88, 107, 118 amplified speakers and, 113–14, 116 Microprocessors, 100, 158, 185 Microscopes, 5, 26, 50, 70, 80, 172, 250 germ theory and, 156, 158 lenses of, 22–24, 27, 141–42 Middle Ages, 137 Miethe, Adolf, 218, 225 Miller, Donald, 58–60 Miller, Grant, 148 Mills, 170, 174 lumber, 52 See also Factories Mirrors, 32, 34–37, 41 lasers and, 235 Renaissance paintings and, 33, 34 in science fiction, 231 in telescopes, 38–40 Moby-Dick (Melville), 202 Modernism, 31, 229 Moon landing, 231 Moore, William, 211 Morse code, 106, 119, 233 Mosquitoes, 62 Mountain time zone, 183 MP3 player, 209, 210 Muckraking, 60, 134, 215, 218, 223 Mumbai, 154 Mumford, Lewis, 34–35 Murano, 17–19, 18, 27, 32, 184, 251 Murray, Annie, 151 Nanoseconds, 187, 190 Nantucket (Massachusetts), 201, 202 Napster, 105 National Association of Broadcasters, 110 National Ignition Facility (NIF), 235–38, 237 Navigation, 168, 170 See also Shipping Neanderthals, 87, 88, 90, 118, 122 Neolithic era, 22, 113 Neon lights, 228–30, 236 Netherlands, 22, 35 Nevada, 191 New Jersey, 206 New Orleans, 55, 110 New York City, 58, 67, 72, 74, 77, 83, 127, 152, 154, 209, 218 artificial light in, 206, 214, 214–15 clock time in, 180, 182, 183 Harlem, 59, 110 Metropolitan Opera, 107 Noise Abatement Society, 114 skyscrapers in, 99–100 slums of, 220, 223–25, 224 subways, 133 Times Square, 229 World’s Fair in, 79 New York State, 72 Tenement House Act (1901), 223 New York Times, 57, 107 NeXT computer, 254 Nobel Prize, 142, 190 Noise abatement, 114–15 Nordhaus, William D., 204–5 Nundinal calendar, 165 Nuremberg rallies, 8, 114 Oakland (California), 151 Obama, Barack, 83 Observatories, 38–39, 164, 183 Odorono antiperspirant, 151 Ogden, William Butler, 128 Oil lamp, 199 On the Origin of Species (Darwin), 4, 253 One Hundred Years of Solitude (García Márquez), 50 On the Various Contrivances by Which British and Foreign Orchids are Fertilised by Insects, and the Good Effects of Intercrossing (Darwin), 253 Pacific time zone, 183 Paleolithic era, 88 Palmolive soap, 151 Paramount Pictures, 77, 79 Paris, 66, 83, 87, 127, 133, 138, 152, 163, 190, 226 Academy of Sciences, 96 chandlers in, 198 Grand Palais, 228 University of, 88 Pasteur, Louis, 142 Patents, 25, 102, 107, 148, 215 of laser, 232 of lightbulb, 206 of neon lights, 228 of phonautograph, 65–66, 92 Pendulums, 6, 166, 170, 171, 176, 184, 185 Petroleum, 203–4 Philadelphia, 58 Philip III, King of Spain, 168 Philip IV, King of Spain, 32 Phonautograph, 92, 93, 94, 95–97, 118, 253 Phonograph, 92, 97–98, 205, 206, 252 Photography, 217, 218, flash (Blitzlicht), 218, 222, 224, 225 lenses for, 25, 27, 42 of tenement conditions, 218, 222–26, 224 Physics, 16, 59, 170, 250 atomic, 187, 188, 190, 191 experimental, 27 of motion, 166, 184 of sound, 90–91, 124 Pierce, John, 232 Piezoelectricity, 184–85 Pisa, Duomo of, 164–66, 167, 190 Pixar, 254 Pleistocene era, 127 Polsby, Nelson W., 81 Pork, preserved, 68, 127 Postmodern architecture, 226, 230 Postum Cereal Company, 74 Prelude, The (Wordsworth), 176 Printing press, 7, 20, 22, 32, 52, 197 air-conditioning and, 76 demand for spectacles generated by, 4, 22, 251 scientific revolution and, 25 Progressive Era, 223 Public health, 140, 142–45, 148–50, 154 Pullman, George, 130, 131 Pullman (Illinois), 132 Pygmalion (Shaw), 138 Quantum mechanics, 10, 41 Quartz, 19, 184–87, 190, 192 Radiation, 187, 190 electromagnetic, 108 Radio, 100, 105–8, 109, 110, 112–13, 121, 184 advertising on, 151–52 Morse code transmitted by, 119 noise of, 115 Radiocarbon dating, 190–92 Railroads, 59–61 refrigerator cars on, 59–60 timekeeping and, 178, 180, 182–83, 189 Refrigeration, 46, 59–61, 64–68, 250 frozen foods made possible by, 70, 76 ice-powered, 57, 59 science behind invention of, 64–65 Rembrandt van Rijn, 31, 35 Renaissance, 31, 32, 35–37, 90 Republican Party, 81 Reznikoff, Iegor, 88 Richards, Keith, 116 Riis, Jacob, 218, 220, 221, 222–26, 224 Rio de Janeiro, 45, 53, 83, 128 Rivoli Theater, 77, 80 Robbins, Marty, 115 Robotics, 158 Roebuck, Alvah, 178 Rockefeller, John D., 149 Roman Catholic Church, 25 Roman Empire, 2, 198 glass objects from, 14, 15 Romanticism, 176, 241, 242, 252 Rome, ancient, 154, 165, 226 Ronettes, 88 Roosevelt, Theodore, 220 Royal College of Science, 27 Royal Navy, British, 120 Royal Society, 242 Russell, Charles Edward, 60 Rust Belt, 83 Sackett & Wilhelms printing company, 78 Sahara, 13 St.

The Relentless Revolution: A History of Capitalism

by

Joyce Appleby

Published 22 Dec 2009

With the Civil War behind it, the United States could turn toward developing the vast tracks of unoccupied land acquired in 1803 in the Louisiana Purchase and through the treaty that ended the Mexican-American War in 1848. Meanwhile its urban population had been exploding. Total population grew twelvefold between 1800 and 1890 while those living in cities increased an astonishing eighty-seven times. Gustavus Franklin Swift helped forge economic ties across the continent with his invention of refrigerated railroad cars. Now the cattle ranging over the grazing lands west of the Mississippi River could be driven to Omaha, Kansas City, and Chicago to be slaughtered and their dressed meat shipped to the densely populated, urbanized East. In a society where almost everyone could afford to eat meat, refrigeration furnished the missing link between supply and demand.

We the Corporations: How American Businesses Won Their Civil Rights

by

Adam Winkler

Published 27 Feb 2018

Not only did the transcontinental railroad enable people to cross the country with ease—something that could be appreciated by Field, whose first journey to California more than twenty years earlier had taken six weeks on a boat packed with cholera-infected passengers—but goods moved easily too. Railroads transported more than 350 million tons of freight each year and employed upwards of 1.5 million people. The new refrigerated railroad cars brought fresh fruits and vegetables grown in Florida and California to markets across the nation, a sign of the truly national economy.42 Field thus had little sympathy for the populist heirs to Jefferson, Jackson, and Taney who enacted laws subjecting successful businesses like the railroads to special, disadvantageous rules and taxes.

Owning the Earth: The Transforming History of Land Ownership

by

Andro Linklater

Published 12 Nov 2013

Fanning out from Chicago, more railroads connected ranchers and livestock farmers to the Union stockyards where four hundred million animals were slaughtered between 1865 and 1900 to be redistributed as meat to the rest of the country. Before the end of the century, California fruit growers would be packing a quarter of a million tons of oranges, grapes, lettuces, and almonds into refrigerated railroad cars to add to the cascade of eastward-heading food. The flood of produce from the Midwest, railroaded into Chicago then shipped east in freight trains or by barge down the Erie Canal, prompted one New York observer to boast that the city “may call Ohio her kitchen garden, Michigan her pastures, and Indiana, Illinois and Iowa her harvest fields.”

The Box: How the Shipping Container Made the World Smaller and the World Economy Bigger

by

Marc Levinson

Published 1 Jan 2006

Albert Fishlow also rejects Rostow’s claim that railroad construction was essential in stimulating American manufacturing, but contends that cheaper freight transportation had important effects on agriculture and led to a reorientation of regional economic relationships; see American Railroads and the Transformation of the Ante-Bellum Economy (Cambridge, MA, 1965) as well as “Antebellum Regional Trade Reconsidered,” American Economic Review (1965 supplement): 352–364. On the role of railroads in Chicago’s rise, see William Cronon, Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West (New York, 1991), and Mary Yeager Kujovich, “The Refrigerator Car and the Growth of the American Dressed Beef Industry,” Business History Review 44 (1970): 460–482. For an example from Britain, see Wray Vamplew, “Railways and the Transformation of the Scottish Economy,” Economic History Review 24 (1971): 54. On transportation and urban development, see James Heilbrun, Urban Economics and Public Policy (New York, 1974), p. 32, and Edwin S.

…

“Globalization and the Inequality of Nations.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 110, no. 4 (1995): 857–880. Kuby, Michael, and Neil Reid, “Technological Change and the Concentration of the U.S. General Cargo Port System: 1970–88.” Economic Geography 68, no. 3 (1993). Kujovich, Mary Yeager. “The Refrigerator Car and the Growth of the American Dressed Beef Industry.” Business History Review 44 (1970): 460–482. Lamoreaux, Naomi R., Daniel M. G. Raff, and Peter Temin. “Beyond Markets and Hierarchies: Toward a New Synthesis of American Business History.” American Historical Review 108 (2003). Larson, Paul D., and H.

…

Propeller Club Prudential Lines Prussia public loaders Puerto Rico: containership service to; disappearance of containers in; and economic development; military shipments to; and shipping costs Pullman Company Qingdao, China Queen Mary Qui Nhon, Vietnam railroads: attitude of toward containerization; before containers; boxcars; and container standardization; and container traffic prior to 1932; deregulation of in United States; and double-stack service; and early containers; flatcars; and New York City; on-dock; and piggyback service; and ports; and rate structures; refrigerated cars; and ship lines; and track standardization Ramage, Lawson rebates retailers revenue bonds Reynolds (R. J.) Industries Ricardo, David Richardson, Paul Richmond, CA Rockefeller, David Roger, Sidney roll on-roll off ships Rosenberg, Nathan Rostow, W. W. Rotterdam: as European container center; labor arrangements in; among largest ports; services to Ryan, Joseph Sager, Karl Heinz Saigon, Vietnam St.

A Few Red Drops: The Chicago Race Riot of 1919

by

Claire Hartfield

Published 1 Jan 2017

Before Swift’s investment in this groundbreaking innovation, there was no way to keep meat fresh long enough to transport it long distances. Most livestock was shipped live to be butchered in branch houses located near the households where the meat would be cooked and eaten. Chicago companies slaughtered and packaged only enough meat to satisfy the needs of local residents. With the development of the refrigerated car in the late 1870s, meat dressed in Chicago could be shipped to the many people living in New York, Boston, and other East Coast cities. The number of cows slaughtered in Chicago grew from a quarter million in 1875 to two and a quarter million in 1890. Next problem: finding uses for all the animal parts that were ending up on the scrap heap.

In Praise of Idleness and Other Essays

by

Bertrand Russell

Published 1 Jan 1935

The trees are all exactly alike, carefully tended and at the right distance apart. The oranges, it is true, are not all exactly of the same size, but careful machinery sorts them so that automatically all those in one box are exactly similar. They travel along with suitable things being done to them by suitable machines at suitable points until they enter a suitable refrigerator car in which they travel to a suitable market. The machine stamps the words “Sunkist” upon them, but otherwise there is nothing to suggest that nature has any part in their production. Even the climate is artificial, for when there would otherwise be frost, the orange grove is kept artificially warm by a pall of smoke.

The Butcher's Guide to Well-Raised Meat: How to Buy, Cut, and Cook Great Beef, Lamb, Pork, Poultry, and More

by

Joshua Applestone

,

Jessica Applestone

and

Alexandra Zissu

Published 6 Jun 2011

We don’t doubt it—we get ack from people who don’t like to see our carts, loaded high with whole animals, wheeled from the street to the back of the shop, so we can only imagine what it was like back in the day with carcasses rolling all over the city. Modernization and economics changed everything. By the midnineteenth century, according to Suzanne, meat production began to shift to the Midwest because of economies of scale. With the development of refrigerated train cars, meat could be transported far and wide, and things began to change for the worse. Modernization was also at the heart of the near-death of the small butcher shop. The one-two punch was the rise of home refrigeration, which eliminated the need to shop for meat daily, and the convenient one-stop shopping of supermarkets that took o after World War II.

A Splendid Exchange: How Trade Shaped the World

by

William J. Bernstein

Published 5 May 2009

He settled on one invented by Andrew Chase that featured easily loaded twin overhead ice tanks at either end, a configuration later improved on by another meat packer, Philip Armour, who added an effective cooling mixture of crushed ice and salt.38 By 1880, the railroads and private shippers owned more than 1,300 ice-cooled refrigerated cars; by 1900, that number swelled to 87,000. The number finally peaked in 1930 at 181,000 cars.39 In 1875, the American beef distributor Timothy Eastman shipped the first chilled meat from New York to England. He packed about onefourth of the volume of the hold with ice and cooled the adjacent cargo with ventilation fans.

…

Tudor's Calcutta trade, which grew steadily more profitable for nearly half a century following his initial delivery in 1833, came to an abrupt end a few years after the opening of the city's first artificial ice plant in 1878.40 Figure 12-3. Schematic of Early Mechanical Refrigeration Unit Artificial and natural production complemented each other nicely; ice made in plants in New Orleans or California filled the cooling tanks of northbound and eastbound refrigerator cars; blocks harvested from midwestern rivers and New England ponds cooled south- and westbound freights. Timothy Eastman's partner, Henry Bell, suspected that the new artificial refrigeration machines might prove more economical than ice for marine shipping. In 1877 he approached the famous physicist Sir William Thompson (later Lord Kelvin) about the feasibility of transporting artificially chilled and frozen beef.

Drink: A Cultural History of Alcohol

by

Iain Gately

Published 30 Jun 2008

When, in 1917, the issue of Prohibition had been threatened to be overshadowed by the entry of the United States into World War I, the ASL had turned the conflict to its advantage. The drain on resources created by alcoholic beverages was exaggerated in the most lurid language by ASL propagandists: “Brewery products fill refrigerator cars, while potatoes rot for lack of transportation, bankrupting families and starving cities. The coal that they consume would keep the railways open and the factories running.” Abstinence, meanwhile, was promoted as the key to victory over the beer-swilling Germans: “Prohibition is the infallible submarine chaser we must launch by thousands.

…

Demand for grapes was driven by the “nonintoxicating cider and fruit juices” exemption to the Volstead Act, which allowed the manufacture of such drinks for use in the home. The principal out-of-state destination for California “juice” grapes was New York, followed by Chicago. These places were supplied via a market at the Pennsylvania Railroad yard, to which growers shipped their products in refrigerated cars. The scale of business was titanic: “In 1928 one buyer bought 225 carloads (3,100 tons) of grapes in a single purchase.” As Business Week observed, “The only inference is that these grapes went to someone who is manufacturing wine in vast quantities.” The periodical labeled the Penn yard “the Wall Street of the grape auction business” and described the procedure by which grapes were sold on to the public: “The ordinary speculator buys two or three cars and has them shipped to a siding in his own neighborhood.

Future Crimes: Everything Is Connected, Everyone Is Vulnerable and What We Can Do About It

by

Marc Goodman

Published 24 Feb 2015

That means every time you go to your refrigerator to get ice, you will be presented with ads for products based on the food your refrigerator knows you’re most likely to buy. Screens too will be ubiquitous, and marketers are already planning for the bounty of advertising opportunities. In late 2013, Google sent a letter to the Securities and Exchange Commission noting, “we and other companies could [soon] be serving ads and other content on refrigerators, car dashboards, thermostats, glasses, and watches, to name just a few possibilities.” Knowing that Google already reads your Gmail, records your every Web search, and tracks your physical location on your Android mobile phone, what new powerful insights into your personal life will the company develop when its entertainment system is in your car, its thermostat regulates the temperature in your home, and its smart watch monitors your physical activity?

…

LORD KELVIN One of the greatest challenges we face with our current technological insecurity is that there are often few if any telltale signs of hacker intrusions into our networks and devices. The obvious problem is that you have unwanted guests (whether or not you realize it). The greater conundrum is that you can’t fight what you can’t see. Across our smart phones, laptops, tablets, bank accounts, refrigerators, cars, corporate networks, and electrical grids, there are ghosts in our machines. Keeping out all intruders at all times was a worthy if quaint goal. But in case you hadn’t noted, the proverbial technological republic has fallen. Our technology is riddled with bugs, flaws, and invaders. Today, regretfully, our goal can no longer be purely prevention.

The Locavore's Dilemma

by

Pierre Desrochers

and

Hiroko Shimizu

Published 29 May 2012

As the environmental historian William Cronon pointed out in 1991, however, while the stated goal of the movement was to “secure the highest sanitary condition” for consumers, public health was in fact “a convenient way of putting the best face on a deeper and more self-interested economic issue.”33 In fact, health complaints about smaller slaughterhouses and urban dairy operations long predated the rise of the Chicago packers and were common in other countries.34 According to economists Donald Boudreaux and Thomas DiLorenzo, the most plausible explanation for the adoption of the first antitrust legislation in Missouri in 1889 is to view it as an attempt by politically powerful local producer groups, mostly independent retail butchers, to shield themselves from the lower prices and intense competitive pressures of Chicago packers.35 In the meantime, other small-scale attempts to circumvent the packers were set up in locations closer to production sites. One such initiative was spearheaded by a Frenchman, the Marquis de Mores, who not only built a number of slaughterhouses and cold storage houses in Montana and in what is now North Dakota, but also procured refrigerator cars. The venture, however, failed miserably. As the economic historian Fred A. Shannon observes: “Because the supply of matured beef was not year-round, slaughtering on the Plains proved impractical except for taking care of the local market . . . Furthermore, only medium-grade cattle were offered, and the small slaughterhouses were not equipped to make use of the by-products that furnished so much of the profits for the greater packers.”36 Despite small-scale butchers and some cattlemen’s recriminations,37 consumers ultimately voted with their wallets and purchased the offerings of the more efficient large-scale operations.

An Economist Gets Lunch: New Rules for Everyday Foodies

by

Tyler Cowen

Published 11 Apr 2012

In the nineteenth century, Americans ate more pork than beef. Pork was easier to salt, preserve, and store. Salted and preserved hams remain prominent in the South, but most customers prefer their meat fresh, which favors beef more than many forms of pork. U.S. beef gained significant ground only with the advent of refrigerated train cars, as discussed in chapter 2, which allowed entrepreneurs to ship Midwest beef around the country without much risk of spoilage. In the United States beef consumption equaled pork consumption by the time of World War I. By the 1950s, beef had become decisively more important. Parts of northern Mexico, including near Juárez, are an exception.

Green Gold

by

Sarah Allaback

Published 14 Mar 2025

As Hass and Brokaw worked to slowly expand their plantings, Calavo Growers’ strategic advertising campaign for 1936 capitalized on its last successful year, with national newspaper stories aimed at appropriate regional markets across the country.35 All of a sudden, it seemed, the possibility of lowering the price to fit the budget of a middle-class housewife had become a reality. Calavo Growers used the feedback from Crosby’s survey to develop ads targeted at different regions. Calavos were delivered in refrigerated train cars to supermarkets throughout the tri-city area of Davenport, Iowa, and Rock Island and Moline, Illinois. In Detroit, Calavos sold for ten to fifteen cents, and that discount down from seventy-five cents also came with new benefits—the former salad fruit had proved itself extraordinarily versatile and now could star as a main course or memorable dessert.

The Great Divergence: America's Growing Inequality Crisis and What We Can Do About It

by

Timothy Noah

Published 23 Apr 2012

Millions of Americans of the older generation still remember what it was like to go upstairs of an evening and then be consumed with worry as to whether they had really turned off completely the downstairs gas jets. A regular chore for the rural housewife was filling the lamps … For a good many years there had been refrigerator cars on the railroads, but the great national long-distance traffic in fresh fruits and vegetables was still in its infancy … In most parts of the United States people were virtually without fresh fruit and green vegetables from late autumn to late spring. During this time they consumed quantities of starches, in the form of pies, doughnuts, potatoes, and hot bread, which few would venture to absorb today.

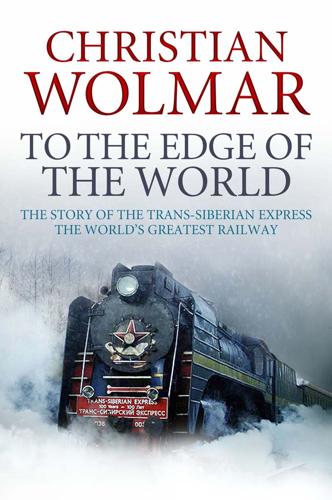

To the Edge of the World: The Story of the Trans-Siberian Express, the World's Greatest Railroad

by

Christian Wolmar

Published 4 Aug 2014

The amount of butter produced in the region increased fivefold in the ten years to 1904, reaching two million puds (the Russian unit which weighs just over 36 lb), which created a profitable export market to Britain, Denmark and Germany. Butter trains became one of the regular features of the line. The butter was transported in refrigerator cars, distinctive because they were painted white, and whole trains could be seen running up and down the line. The trade was huge: ‘In the early summer peak period about a dozen trains, each of 25 cars, were despatched each week.’17 This vast agricultural produce of Siberia was not only for export.

Cool: How Air Conditioning Changed Everything

by

Salvatore Basile

Published 1 Sep 2014

Anyone traveling in hot weather learned that an open window was a bad idea; it brought in all the dust kicked up by that speed, as well as smoke, soot, live cinders, and an occasional metal splinter blown back from the engine. By the 1850s, traveling by rail had gained the reputation of being a sweaty, filthy experience, especially as the introduction of ice-cooled refrigerator cars had meant that beef carcasses could travel more comfortably than people. But prospective inventors were trying to fill the gap with hundreds of “ventilation” contraptions designed for railroad travel. With straight-faced relish, Scientific American described them; an 1852 article went through seven inventions, ranging from “a refrigerator filled with ice or water, which purifies the air above intended for ventilation, there being between the floor of the car and the refrigerator a false bottom” to “a long flexible tube, running the whole length of the train from the fire-box to the locomotive, with branch-pipes let into the top of each car, the commencement of the pipe near the engineer being funnel-shaped, so that air can easily rush in.”

The Human Age: The World Shaped by Us

by

Diane Ackerman

Published 9 Sep 2014

214“when, by the glimmer of the half-extinguished light”: Mary Shelley, Frankenstein, chapter 5. 230On September 14, 2013, the annual Loebner Prize for robots that can pass for human went to a chatbot named Mitsuku. However, it ultimately gave itself away in December with this exchange. Q: “Why am I tired after a long sleep?” A: “The reason is due to my mental model of you as a client.” 231“Can we live inside a house”: Technological inventions, such as refrigerators and refrigerated train cars, made frozen food possible, including nutritious out-of-season foods, such as frozen fruits and vegetables. As canning opened up the frontiers and women’s home lives, food production became more and more industrialized. With these and other innovations, between WWI and WWII, a massive change in domesticity took place.

The Liberation Line: The Untold Story of How American Engineering and Ingenuity Won World War II

by

Christian Wolmar

Published 15 Dec 2024

Transporting prisoners of war was a key function of the railways because trucks were rarely available. One transport ended in a horrific—and little reported—incident in which dozens of German prisoners perished. On January 22, 1945, a train taking prisoners of war from Aachen to Belgium included two refrigerated cars with the cooling mechanism disconnected. However, according to Livingstone, the historian of the 740th: “The men in charge of loading the prisoners, not knowing that such cars are manufactured airtight, locked the doors.”22 When the doors of the train were opened at Charleroi after an overnight journey, all the prisoners in one car and three-quarters in the other had died of suffocation.

Culture works: the political economy of culture

by

Richard Maxwell

Published 15 Jan 2001

A typical 62 Beer brew actually starts with raw materials produced through Busch Agricultural Resources. It is then canned, bottled, packaged, and labeled by AnheuserBusch divisions that handle metal containers, packaging, printing, and labeling. Transportation to and from the brewery is handled by Manufacturers Railway Corporation and the St. Louis Refrigerator Car Company, both owned and operated by Anheuser-Busch. Anheuser-Busch’s recycling subsidiary even handles the product after consumption. The brewery’s control does not stop at the doors of its impressive array of subsidiary companies. It also exercises a sustained pressure on the wholesalers that distribute its product to retailers.

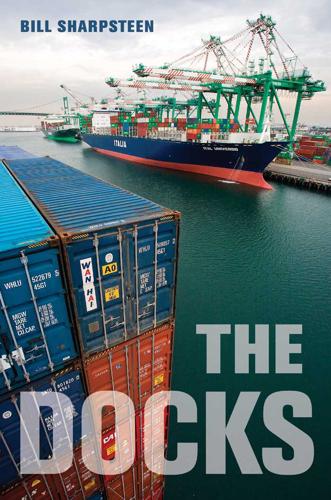

The Docks

by

Bill Sharpsteen

Published 5 Jan 2011

Stories in the San Francisco Daily News depicted a morality play of sorts in which the longshoremen—most often referred to as rioters—received a suitable punishment for their attacks on the port and the police protecting it. More sympathetic, prolabor accounts characterized the strikers’ actions as purely defensive, even heroic, and described the cops as overly aggressive tools of the employers. The battle began early, at 8:00 a.m., after a Belt Line locomotive driven by strikebreakers shunted two refrigerator cars into the Matson docks at piers 30 and 32. According to the Daily News, the pickets—a crowd of about two thousand—protested this by setting two boxcars on fire. The police reacted with tear gas, vomiting gas, and gunfire. At one point, so much ammunition was released that workers on the construction site of the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge had to run for cover lest they stop a stray bullet.

On the Road

by

Jack Kerouac

Published 1 Jan 1957

He and I and Ed Dunkel ran across the tracks and hopped a freight at three individual points; Marylou and Galatea were waiting in the car. We rode the train a half-mile into the piers, waving at switchmen and flagmen. They showed me the proper way to get off a moving car; the back foot first and let the train go away from you and come around and place the other foot down. They showed me the refrigerator cars, the ice compartments, good for a ride on any winter night in a string of empties. “Remember what I told you about New Mexico to LA?” cried Dean. “This was the way I hung on ...” We got back to the girls an hour late and of course they were mad. Ed and Galatea had decided to get a room in New Orleans and stay there and work.

An Extraordinary Time: The End of the Postwar Boom and the Return of the Ordinary Economy

by

Marc Levinson

Published 31 Jul 2016

Over the ensuing ten years, manufacturers had invested massively in the latest Western machinery, raising output per work hour more than 10 percent per year, compounded, even as they added millions of jobs. After adjusting for inflation, Japan’s income per person had more than doubled, enabling millions of consumers to buy refrigerators, cars, and color televisions. Work was to be had for the asking. Companies were so desperate to hold on to labor that they promised restive workers jobs for life, a new practice that was soon deemed a venerable tradition.2 By 1970, though, the elite bureaucrats responsible for planning Japan’s future at the Ministry of International Trade and Industry, known as MITI, began to worry that the economy would soon fall to earth.

Wasteland: The Dirty Truth About What We Throw Away, Where It Goes, and Why It Matters

by

Oliver Franklin-Wallis

Published 21 Jun 2023

Obsolescence went radically against the existing notions of the time, in which businesses had competed to build products that were of the highest quality; Henry Ford, for example, built the Model T to be repairable and long-lasting, while declaring, ‘We want the man who buys one of our cars never to have to buy another.’19 But obsolescence, like disposability, really experienced its golden age in the mid-1950s, as the post-war boom began to slow. Manufacturers were realising that once everyone had a TV, refrigerator, car, and radio, they needed to create reasons for them to ‘upgrade’ to newer models. With durable goods, that required making goods, well, less durable. As Victor Lebow, a marketing consultant writing in the Journal of Retailing, put it in 1955: ‘Our enormously productive economy demands that we make consumption our way of life, that we convert the buying and use of goods into rituals, that we seek our spiritual satisfactions, our ego satisfactions, in consumption… We need things consumed, burned up, worn out, replaced, and discarded at an ever increasing rate.’20 Waste was no longer just a side-effect – it was the goal.

How the World Ran Out of Everything

by

Peter S. Goodman

Published 11 Jun 2024

After local men deployed to quell the strikers took the side of the workers, Scott persuaded state authorities to bring in militia forces from Philadelphia, on the other side of the state. As six hundred troops arrived in railcars on the afternoon of July 21, they absorbed the spectacle of two thousand train cars and locomotives37 sitting motionless. Water from melting ice seeped from refrigerated cars full of meat rotting in the midsummer heat. Heaps of fruit and vegetables sat decomposing. Waylaid in Pittsburgh “were all the necessities38 and most of the luxuries of nineteenth century civilization,” wrote Bruce. “Clothing, furniture, books, whisky, silverware, oil, coal, flour, machinery, carpets, ornaments—everything from cribs to coffins.”

What Technology Wants

by

Kevin Kelly

Published 14 Jul 2010

The space shuttle has tens of millions of physical parts, yet it contains most of its complexity in its software, which is not included in this assessment. Complexity of Manufactured Machines. The number of parts (shown as powers of 10) used in the most complicated machines of each era over two centuries. Our refrigerators, cars, and even doors and windows are more complex than two decades ago. The strong trend for complexification in the technium provokes the question, how complex can it get? Where does the long arc of complexity take us? The thrust of 14 billion years of increasing complexity cannot stop today. But when we try to imagine a technium with another million years of complexity accruing at the current rate, we shudder.

Blood, Iron, and Gold: How the Railways Transformed the World

by

Christian Wolmar

Published 1 Mar 2010

It was a massive business which at its height provided two thirds of a ton for every person living in a major city. The trade declined in the 1890s with the development of cooling equipment but that, in turn, spawned another commercial opportunity for the railroads, the transport of perishables such as fruit and fish in refrigerated cars, such as the already quoted example of Argentinian beef. The list, therefore, is endless. The railways carried everything, from newspapers to nuts, minerals to mail, at a cost that was invariably cheaper than the alternative, even when monopolistic railways exploited their position. The Railway News in 1864 mentioned trains arriving at a London goods yard every ten minutes in the morning laden with ‘Manchester packs and bales, Liverpool cotton, American provisions, Worcester gloves, Kidderminster carpets, Birmingham and Staffordshire hardware, crates of pottery from North Staffordshire and cloth from Huddersfield, Leeds, Bradford and other Yorkshire towns…’ 27 Think of the most obscure industry and then discover how the railways changed it.

Off the Books

by

Sudhir Alladi Venkatesh

She decided to borrow $2,500 from a local creditor (at 30 percent interest) to buy lights and a speaker system so that the gangs could host weekend parties. Leroy borrowed $500 from Ola to purchase ten used microwaves, which he then sold in the back of his store for $750; he continues to buy used electronic equipment (some of which is stolen), including refrigerators, car stereos, computers, and televisions, and estimates that this business accounts for 30 to 40 percent of his total revenues. Persius, the manager of a dollar store, asked a creditor for $3,000 so that he could buy the unsold cell phones from a neighboring merchant; he sold cell phones on one side of the store, and, two years later, removed the dollar items and sold only phones and phone-related accessories.

Physics of the Future: How Science Will Shape Human Destiny and Our Daily Lives by the Year 2100

by

Michio Kaku

Published 15 Mar 2011

Why couldn’t he simply go to the supermarket, they ask, and get some oregano? But in the days of Columbus, spices and herbs were extremely expensive. They were prized because they could mask the taste of rotting food, since there were no refrigerators in those days. At times, even kings and emperors had to eat rotten food at dinner. There were no refrigerated cars, containers, or ships to carry spices across the oceans.) That is why these commodities were so valuable that Columbus gambled his life to get them, although today they are sold for pennies. What is replacing commodity capitalism is intellectual capitalism. Intellectual capital involves precisely what robots and AI cannot yet provide, pattern recognition and common sense.

Behind the Berlin Wall: East Germany and the Frontiers of Power

by

Patrick Major

Published 5 Nov 2009

‘The presence in Berlin of an open and essentially uncon- trolled border between the socialist and capitalist worlds’, complained Soviet ambassador Pervukhin in 1959, ‘unwittingly prompts the population to make a comparison between both parts of the city, which, unfortunately, does not always turn out in favour of Democratic [East] Berlin.’¹⁵⁸ In one Leipzig office conversations revolve exclusively around the satisfaction of personal needs. For instance on the supply of televisions, refrigerators, cars etc., and on the price differences of consumer goods ¹⁵¹ MfS-BV Potsdam, ‘Einschätzung der Lage im Grenzgebiet am Ring um Westberlin’, 13 May 1960, BStU-ZA, Allg. S 204/62, viii, fos. 105–9. ¹⁵² SED-BPO Carl Zeiß Jena, ‘Informationsbericht’, 19 Oct. 1960, SAPMO-BArch, DY30/IV2/ 5/843, fos. 155–61. ¹⁵³ Tausend kleine Dinge: Reparaturen und Dienstleistungen (1960), SAPMO-BArch, DY30/ IV2/6.08/10, fos. 1–17. ¹⁵⁴ SED-KL Leuna to SED-BL Halle, 23 Nov. 1960, LAM, BPA SED Halle, IV2/5/663, fos. 118–21. ¹⁵⁵ ‘Bericht über die Lage im Wohnraum in Jena’, 23 Sept. 1960, SAPMO-BArch, DY30/IV2/5/ 843, fos. 162–7. ¹⁵⁶ Taken from BA, DA-5/5999. ¹⁵⁷ MfS-ZAIG, ‘Bericht über die Entwicklung der Republikflucht im Zeitraum Oktober-Dezember 1960 . . . ’, 3 Feb. 1961, BStU-ZA, ZAIG 412, fo. 14. ¹⁵⁸ Harrison, Driving, 99. 52 Behind the Berlin Wall compared with the western zone, such as nylon stockings and the fact that personal freedom is restricted because the GDR did not have enough holiday resorts.¹⁵⁹ By mid-1961 the SED leadership was acknowledging that it was in an economic crisis.

The Great Railroad Revolution

by

Christian Wolmar

Published 9 Jun 2014

And the railroads could not be accused of a lack of innovation. One key development in the 1880s was the widespread introduction of the refrigerated boxcar. Although there had been earlier attempts to use refrigeration to keep cars cool, it was only in the 1880s that satisfactory methods were developed. The new refrigerated cars revolutionized the transportation of beef, since the animals could now be slaughtered locally before being transported to the Chicago stockyards; as a result, these yards grew to enormous proportions, eventually employing forty thousand people in the 1920s and processing nearly all of America’s meat.

Coffeeland: One Man's Dark Empire and the Making of Our Favorite Drug

by

Augustine Sedgewick

Published 6 Apr 2020

* * * — THE WHEAT BOOM that followed the gold rush transformed California’s landscape, and so did the subsequent wheat bust. By the 1880s, the state’s grain fields had become so highly mechanized that production outpaced global demand. The resulting fall in prices encouraged landowners to shift their resources to new crops: sugar beets, vegetables, and especially tree and vine fruits. With the arrival of the refrigerator car in 1888, the orchards and groves of the great valleys, San Joaquin, Salinas, Sacramento, Santa Clara, and others, became California’s new gold mines, producing oranges, lemons, plums, pears, grapes, apples, figs, dates, apricots, olives, and more. Orchard crops accounted for only 4 percent of the value of California’s agricultural produce in 1879.

The Cold War

by

Robert Cowley

Published 5 May 1992

The aircrews typically deplaned in temperatures of 35 degrees below zero (in an era when windchill factors were unheard of), in a region devoid of vegetation and covered in snow, at a time of year when darkness ruled nearly twenty-four hours a day. Maintenance crews and flight crews alike were quartered in what looked like railroad refrigerator cars, down to the levered door handles. Toilets operated via the “armstrong” flush system—hand-pumped. After receiving Arctic clothing, including fur-lined parkas and mukluks, the crews spent the first week in Arctic survival training and practicing Arctic flight operations: takeoffs and landings on ice-covered runways, navigating over the Pole, and air refueling in radio silence.

Meat: A Benign Extravagance

by

Simon Fairlie

Published 14 Jun 2010

Centralized processing units also generate a form of cross-haulage: It has always seemed absurd to me that Kansas farmers should ship wheat to Minneapolis and then have flour shipped all the way back from Minneapolis to Kansas … . In the milling of flour – which lends itself so admirably to local production – we have drifted into a state of affairs where ten of the national mills are able to supply 50 per cent of the consumption of the country. The same applies to meat: The development of the refrigerator car made it possible to ship fresh meats great distances … As a result we now have the absurd system whereby the raw products of an industry, in this case the livestock, are shipped great distances to the meat packing centres and then, after being slaughtered, shipped equally great distances back to the point of origin.61 Borsodi wrote several other books, including one called Flight from the City, which was a practical guide to rural self-reliance.

Big Debt Crises

by

Ray Dalio

Published 9 Sep 2018

–New York Times March 27, 2008 A Downturn as Data Revives Pessimism “Wall Street pulled back on Wednesday after a drop in durable goods orders for February injected more pessimism about the economy into the stock market. The Dow Jones industrial average fell nearly 110 points...Investors were disappointed to see a 1.7 percent dip last month in orders for durable goods, which are costly items like refrigerators, cars and computers. The drop followed a decline of 5.3 percent in January.” –Associated Press April 1, 2008 Stocks Surge on Hopes Financial Woes Are Easing “Despite the discouraging numbers—$19 billion in write-downs at UBS and nearly $4 billion at Deutsche in the first quarter alone—investors appeared hopeful that the bad news could signal the last of Wall Street’s subprime woes.”

Reminiscences of a Stock Operator

by

Edwin Lefèvre

and

William J. O'Neil

Published 14 May 1923

And then I discovered that not only had he wiped out the debt entirely but I had a small credit balance besides. 3.8Livermore is likely referring to the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad that operated from New York City down along the Atlantic seaboard to Tampa, Florida. It was formed through combination of smaller lines in 1869 by William Walters, a produce merchant from Baltimore. In addition to transporting vacationers to the tropical waters of the Gulf of Mexico, the Southern Atlantic moved fresh fruit and vegetables in refrigerator cars to northern cities. In the late 1950s, the railroad merged with its old rival, the Seaboard Coast Line, before becoming part of CSX.26 I think I could have run that up without much trouble, for the market was right, but he said to me, “I have bought you ten thousand shares of Southern Atlantic.” 3.8 That was another road controlled by his brother-in-law, Alvin Marquand, who also ruled the market destinies of the stock.

Americana: A 400-Year History of American Capitalism

by

Bhu Srinivasan

Published 25 Sep 2017

To raise cash, he allowed the newly named Anheuser-Busch to maintain and operate the Budweiser brand. He would never find the means or methods to get it back. With Conrad’s misfortune, the Budweiser name would become the flagship brand of Anheuser-Busch. Before long, it would become clear that the brand was worth more than all of the brewing facilities, refrigerated cars, bottling machines, and warehouses combined. This idea of the trademark was less important when businesses were largely named after their local proprietors serving local markets, but this era of national markets would see the widespread use of invented names for products, often pulling clever derivatives and amalgamations from the English language.

Americana

by

Bhu Srinivasan

To raise cash, he allowed the newly named Anheuser-Busch to maintain and operate the Budweiser brand. He would never find the means or methods to get it back. With Conrad’s misfortune, the Budweiser name would become the flagship brand of Anheuser-Busch. Before long, it would become clear that the brand was worth more than all of the brewing facilities, refrigerated cars, bottling machines, and warehouses combined. This idea of the trademark was less important when businesses were largely named after their local proprietors serving local markets, but this era of national markets would see the widespread use of invented names for products, often pulling clever derivatives and amalgamations from the English language.

Palo Alto: A History of California, Capitalism, and the World

by

Malcolm Harris

Published 14 Feb 2023

The gardening work was much more labor-intensive than industrial wheat farming, but the produce sold for a lot more, and the cultivators could vend their products themselves locally or in the surrounding region, vertically integrating their operations and cutting out the middlemen and the speculators. Until the introduction of refrigerated train cars at the end of the 1880s, these perishable goods mostly fed California, not Europe or other nodes on the global market. It’s also worth noting that small, internally diverse plots made for a much stronger food system and a more resilient income stream for the growers. They came to be called truck farms—show up early to a farmer’s market and you’ll know why—and scholars apply the term retrospectively to what were more accurately called cart farms and even bucket farms.

Capital in the Twenty-First Century

by

Thomas Piketty

Published 10 Mar 2014

This is of limited importance for my purposes, however, because durable goods have always represented a relatively small proportion of total wealth, which has not varied much over time: in all rich countries, available estimates indicate that the total value of durable household goods is generally between 30 and 50 percent of national income throughout the period 1970–2010, with no apparent trend. In other words, everyone owns on average between a third and half a year’s income worth of furniture, refrigerators, cars, and so on, or 10,000–15,000 euros per capita for a national income on the order of 30,000 euros per capita in the early 2010s. This is not a negligible amount and accounts for most of the wealth owned by a large segment of the population. Compared, however, with overall private wealth of five to six years of national income, or 150,000–200,000 euros per person (excluding durable goods), about half of which is in the form of real estate and half in net financial assets (bank deposits, stocks, bonds, and other investments, net of debt) and business capital, this is only a small supplementary amount.

The Age of Surveillance Capitalism

by

Shoshana Zuboff

Published 15 Jan 2019

The letter was composed in response to an SEC query on the segmentation of Google’s revenues between its desktop and mobile platforms.16 Google answered by stating that users would be “viewing our ads on an increasingly wide diversity of devices in the future” and that its advertising systems were therefore moving toward “device agnostic” design that made segmentation irrelevant and impractical. “A few years from now,” the letter stated, “we and other companies could be serving ads and other content on refrigerators, car dashboards, thermostats, glasses, and watches, to name just a few possibilities.” Here is at least one endgame: the “smart home” and its “internet of things” are the canvas upon which the new markets in future behavior inscribe their presence and assert their demands in our most-intimate spaces.

Bourgeois Dignity: Why Economics Can't Explain the Modern World

by

Deirdre N. McCloskey

Published 15 Nov 2011

Lives spent trying to figure out what customers want and how to get the item to them in a nonruinous way and how to improve service and quality at a lower cost, one could argue, lead the bourgeoisie to ethical attitudes superior in some ways to those of a haughty aristocracy or an envious peasantry or a proud clerisy. Or at least so Smith argued. Gustavus Franklin Swift of Chicago was not the first to try shipping slaughtered rather than live cattle eastward in refrigerated cars. But he was the first to succeed, in 1880. The major railways balked. They were making too much money shipping live cattle. Had the railways been able to appeal to the government to regulate Swift’s betterment out of existence in the first act, to “protect jobs” on the railways, or to “guard public safety,” they would have done so, and creative destruction would have been smothered in the cradle.

Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller, Sr.

by

Ron Chernow

Published 1 Jan 1997

In 1874, Standard Oil—with that kindly solicitude for the railroads’ welfare that artfully tied them up with myriad strings—began to raise tens of thousands of dollars to build oil-tank cars, which they would then lease to the roads for a special mileage allowance. Decades later, Armour and Company, the Chicago butcher, mimicked the same strategy by buying up refrigerator cars. As the owner of almost all the Erie and New York Central tank cars, Standard Oil’s position grew unassailable: At a moment’s notice, it could crush either railroad by threatening to withdraw its tank cars. It also prodded the railroads into granting favors for tank cars not enjoyed by the small refiners who shipped by barrel.

The Art of Computer Programming: Sorting and Searching

by

Donald Ervin Knuth

Published 15 Jan 1998

The problem of discovering efficient search techniques for these three types of queries is already quite difficult, and therefore queries of more complicated types are usually not considered. For example, a railroad company might have a file giving the current status of all its freight cars; a query such as "find all empty refrigerator cars within 500 miles of Seattle" would not be explicitly allowed, unless "distance from Seattle" were an attribute stored within each record instead of a complicated function to be deduced from other attributes. And the use of logical quantifiers, in addition to AND, OR, and NOT, would introduce further complications, limited only by the imagination of the query-poser; given a file of baseball statistics, for example, we might ask for the longest consecutive hitting streak in night games.