Gambling Man

by Lionel Barber · 3 Oct 2024 · 424pp · 123,730 words

more than throwing a dart at a dart board,’ a lawyer representing the investors wrote in the letter. ‘How many more millions of dollars of shareholder value must be wasted before the board realizes something must be done?’14 Amid a steady drip of allegations of misconduct, SoftBank, with Arora’s blessing

Mood Machine: The Rise of Spotify and the Costs of the Perfect Playlist

by Liz Pelly · 7 Jan 2025 · 293pp · 104,461 words

make itself attractive to future shareholders. “Everything was about shifting to profitability,” a former employee told me. “Everything was about a good IPO, and good shareholder value.” Like other technology companies in the twenty-first century, Spotify spent its first decade claiming to disrupt an archaic industry, scaling as quickly as possible

The Means of Prediction: How AI Really Works (And Who Benefits)

by Maximilian Kasy · 15 Jan 2025 · 209pp · 63,332 words

the compensation of corporate CEOs. From the 1980s onward, the interests of capital owners came to be increasingly understood in terms of the maximization of shareholder value, as reflected in stock prices. This, in turn, prompted a movement to pay CEOs according to stock prices. More precisely, executives’ benefits often include stock

Blank Space: A Cultural History of the Twenty-First Century

by W. David Marx · 18 Nov 2025 · 642pp · 142,332 words

about the role of China in the luxury market, the stock price drops made it clear that the industry badly needed Chinese consumers to increase shareholder value. Meanwhile, streetwear’s absorption into the mainstream weakened its claims to authenticity. Even in 2019, Virgil Abloh had predicted its decline: “I would definitely say

…

pushback for taking money from Big Donut. In an era where we live as “personal brands,” every life decision is made to increase our own shareholder value. Those who want to create something lasting must resist the pull of instant exposure and early buyouts. We need creators to disappear into their own

The Joys of Compounding: The Passionate Pursuit of Lifelong Learning, Revised and Updated

by Gautam Baid · 1 Jun 2020 · 1,239pp · 163,625 words

. The financial metrics might appear attractive, but a parasitic relationship of extracting value from customers (rather than adding value to them) usually ends up destroying shareholder value at some point in the future. On the other, we have companies like Amazon, led by Jeff Bezos, who says, “We’ve done price elasticity

…

hand and use it to underline clichés such as “employees are our greatest assets,” “our future is bright,” “advancing momentum,” and “we aim to create shareholder value.” This kind of meaningless jargon and platitudes diminishes our understanding of the business and our trust in the leadership. When we finish coding a communication

…

.”7 Once a spinoff is complete, its management is freed from the bureaucracy of the parent and is empowered to make changes that will create shareholder value, because if management owns a significant portion of the spinoff’s stock, they will benefit directly. Greenblatt writes, “A strategy of investing in the shares

…

that it restricts realizable growth. —Phil Fisher When businesses treat equity capital as gold, even those with limited internal compounding growth opportunities can create significant shareholder value through disciplined capital allocation. If excess free cash flow cannot be reinvested, then look for sound capital allocation that might result in dividends or value

…

repurchase stock. It is smart capital allocation to raise equity at a low dilution when the shares are trading at steep valuations. To create significant shareholder value, absolute size of the firm does not matter. Profitability matters. Businesses can achieve high returns through high profit margins. Capital efficiency matters. Businesses with a

…

, stay the course. Tying It Together: ROIC with Competitive Advantage and Capital Allocation Critically evaluating the durability of competitive advantage and how capital allocation affects shareholder value can create a variant perception when selecting equities for long holding periods. —Pat Dorsey Combining the key insights from this chapter, we arrive at investing

…

I had ample capital and skilled personnel, to compete with it. —Warren Buffett Capital Allocation Capital allocation is the bridge between intrinsic business value and shareholder value. If a company has high-return investment opportunities internally, it should reinvest heavily. Maturing companies, however, often continue to invest despite declining or low returns

The Art of Scalability: Scalable Web Architecture, Processes, and Organizations for the Modern Enterprise

by Martin L. Abbott and Michael T. Fisher · 1 Dec 2009

Ego at the Door . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 71 Mission First, People Always. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 72 Making Timely, Sound, and Morally Correct Decisions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 73 Empowering Teams and Scalability . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 74 Alignment with Shareholder Value . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 74 Vision . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 75 Mission . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 78 Goals. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 79 Putting Vision, Mission, and Goals Together . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 81 The Causal Roadmap to Success . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 84 Conclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 86 Key Points . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 87

…

smaller Quigo to countless others, this pair has built around-the-clock reliability, which contributed to the creation of hundreds of millions of dollars in shareholder value. A company can’t operate in the digital age without flawless technical operations. In fact, the lack of a not just good, but great, scalable

…

the feedback includes both praise for great performance and information regarding what they can improve. Management is about measuring and improving everything that ultimately creates shareholder value, examples of which are reducing the cost to perform an activity or increasing the throughput of an activity at the same cost. Management is communicating

…

ridiculous to you. Unfortunately, this problem exists in many of our larger client companies and when it happens it not only wastes money and destroys shareholder value, it can create long-term resentment between organizations and destroy employee morale. In this case, let’s assume that an organization is split between an

…

his technology problems, he knows that long term he is going to have to focus his teams on how they can work together and create shareholder value. He implements a tool for defining roles and responsibilities called RASCI for Responsible, Accountable, Supportive, Consulted, and Informed (this tool is defined further in the

…

decision. This information distribution mechanism simply does not scale and results in people reading emails rather than doing what they should be doing to create shareholder value. A partially filled out example matrix is included in Table 2.1. Taking some of our discussion thus far regarding different roles, let’s see

…

even in light of their apparent contradictions. Broadly speaking, as public company executives, managers, or individual contributors, “Getting our jobs done” means maximizing shareholder value. We’ll discuss maximizing shareholder value in the section on vision and mission. Effective leaders and managers get the mission accomplished—great leaders and managers do so by creating

…

can help move the company in the right direction. Johnny recalls that the components of vision are • Vivid description of an ideal future • Important to shareholder value creation • Measurable • Inspirational • Incorporate elements of your beliefs • Mostly static, but modifiable as the need presents itself • Easily remembered Johnny knows that he needs to

…

debate with the operations leader on the topic but believes strongly that any goal related negotiation should never stand as a reason for not creating shareholder value. Johnny makes the operations head the “R” for determining how to accomplish the goal. He believes the operations team can accomplish the goal on its

…

way, the bottom line is affected beneficially, profits go up, and shareholders are willing to pay more for equity. The increase in equity price creates shareholder value. Operations teams are responsible for ensuring that systems are available when they should be available in order to keep the company from experiencing lost opportunity

…

with their systems. Doing that well also contributes to shareholder value by 85 86 C HAPTER 4 L EADERSHIP 101 maximizing productivity or revenue, thereby increasing the bottom line either through increasing the top line or

…

reducing cost. Again, increasing the bottom line (net income or profits) increases the price shareholders would be willing to pay and increases shareholder value. Quality assurance teams help reduce lost opportunity associated with the deployment of a product and the cost of developing that product. By ensuring that the

…

, which is the notion of helping your organization to tie everything that it does back to what is important to the company: the maximization of shareholder value. Key Points • Leadership is influencing the behavior of an organization or a person to accomplish a specific objective. • Leaders, whether born or made, can get

…

. • Be morally straight always. What you allow you teach and what you teach becomes your standard. • Align everything you do with shareholder value. Don’t do things that don’t create shareholder value. • Vision is a vivid description of an ideal future. The components of vision are q Vivid description of an ideal future

…

frame your vision, mission, and goals and help employees understand how they contribute to those goals and how the employee aids in the creation of shareholder value. Chapter 5 Management 101 In respect of the military method, we have, firstly, Measurement; secondly, Estimation of quantity; thirdly, Calculation; fourthly Balancing of chances; fifthly

…

their organizations, and the efficiency of everything. Project and Task Management Good managers get projects done on time, on budget, and meet the expectations of shareholder value creation in the completion of their projects. Great managers do the same thing even in the face of adversity. Both accomplish those tasks based on

…

requires measurements in order to be produced. We believe in creating cultures that support measurement of nearly everything that is related to the creation of shareholder value. With respect to scale, however, we believe in bundling our measurements thematically. The themes we most often recommend for scale related purposes are cost, availability

…

to speak the universal language of business, you will earn the gratitude and respect of your business counterparts. Remember our points regarding the maximization of shareholder value. If you hold a technology management or executive position, you are first and foremost a manager or executive of that business. You must learn to

…

simply aren’t the best at everything. Furthermore, your shareholders really expect you to focus on the things that really create competitive differentiation and therefore shareholder value. So only build things when you are really good at it and it makes a significant difference in your product, platform, or system. Use Commodity

…

value and minimize the returns associated with dedicating internal and expensive resources to any piece of your architecture. Building a database now has very low shareholder value as compared to the alternative of using several commodity databases. Need more database power? Design your application to make use of any number of databases

…

infrastructure, it very often becomes the source of the company’s scalability crisis. Too much time is spent managing the proprietary system that provides “incredible shareholder value” and too little making and creating business functionality and working to really scale the platform. To clarify this point, let’s take a well known

…

? This is one of the most important questions within the build versus buy analysis process. At the heart of this question is the notion of shareholder value. If you are not creating competitive differentiation, thereby making it more difficult for your competition to win deals or steal customers, why would you possibly

…

the competition catches up to us and offers similar functionality? • Can we build this component cost effectively? Are we reducing our cost and creating additional shareholder value and are we avoiding lost opportunity in revenue? Remember that you are always likely to be biased toward building so do your best to protect

…

is dubious regarding the potential returns of such a system. Christine E. Oberman, CEO, is always talking about how they should think in terms of shareholder value creation, so Johnny decides to discuss the opportunity with her. Together, Johnny and Christine walk through the four-part build versus buy checklist. They decide

…

CRM product. Johnny and Christine disagree on whether they are the best builders and owners of the asset. Although they agree that it can create shareholder value, Christine doubts that the engineers they have today have the best skills to build such an interpreter. Christine pushes Johnny to experienced help in interpreters

…

or two for the upcoming board of directors meetings to discuss the ScaleTalk decision. Conclusion Build versus buy decisions have an incredible capability to destroy shareholder value if not approached carefully. Incorrect decisions can steal resources to scale your platform, increase your cost of operations, steal resources away from critical customer facing

…

and revenue producing functionality, and destroy shareholder value. We noted that there is a natural bias toward building over buying and we urged you to guard strongly against that bias. We presented the

…

help you make the right choice. Key Points • Making poor build versus buy choices can destroy your capability to scale cost effectively and can destroy shareholder value. • Cost centric approaches to build versus buy focus on reducing overall cost but suffer from a lack of focus on lost opportunity and strategic alignment

…

the competition catches up to us and offers similar functionality? • Can we build this component cost effectively? Are we reducing our cost and creating additional shareholder value and are we avoiding lost opportunity in revenue? Remember that you are always likely to be biased toward building so do your best to protect

…

the Cost-Value Data Dilemma, citing the option value of data or claiming competitive advantage through infinite data retention, all potentially have dilutive effects to shareholder value. If the real upside of the decisions (or lack of decisions in the case of ignoring the dilemma) does not create more value than the

…

and unprofitable customers nevertheless applies to your data. In nearly any environment, with enough investigation, you will likely find data that adds shareholder value and data that is dilutive to shareholder value as the cost of retaining that data on its existing storage solution is greater than the value that it creates. Just as

…

perceived competitive differentiation should include values and time limits on data to properly determine if the data is accretive or dilutive to shareholder value. • Eliminate data that is dilutive to shareholder value, or find alternative storage approaches to make the data accretive. Tiered storage strategies and data transformation are all methods of cost justifying

…

future of the entire company likely rests with your system remaining consistently available. Why is this decision so important? Ultimately, you are striving to maximize shareholder value. If you make a decision to spend capital investing in hardware and data center space, this takes cash away from other projects that you could

…

are more indicative of “where the problem is” rather than that a problem exists. The best metrics here are directly correlated to the creation of shareholder value. A high shopping cart abandonment rate and significantly lower click through rates are both indicative of likely user experience problems that are negatively impacting your

…

predictive monitoring solution, but at the very least, they should be identified at the point at which they start to cause customer problems and impact shareholder value. In many mature monitoring solutions, the monitoring system itself will be responsible not only for the initial detection of an incident but for the reporting

…

of “Is there a problem?” The types of monitors that answer these questions best are tightly aligned with the business and technology drivers that create shareholder value. Most often, these are real-time monitors on transaction volumes, revenue creation, cost of revenue, and customer interactions with the system. Third-party customer experience

…

a way to produce the product, they are a limitation on the quantity that can be produced, and they are either accretive or dilutive to shareholder value, depending upon their level of utilization. Taking and simplifying the automotive industry as an example, new factories are initially dilutive as they represent a new

…

repeatability and then specifically for what steps are right for your particular team in terms of complexity. Too much process can stifle innovation and strangle shareholder value, whereas if you are missing the processes that allow you to learn from both your past mistakes and failures, you will very likely at least

…

, a single failure will likely not cause any customer impacting issues. The best measure of availability will have a direct relation to the maximization of shareholder value; this maximization in turn likely considers the impact to customer experience and the resulting impact to revenue or cost for the company. C USTOMER C

…

Disks), 412 mapping data, 420–423 MapReduce program, 420–423 option value of data, 414–415, 416 peak utilization time, 413 reducing data, 420–423 shareholder value, diluting, 415 strategic advantage value of data, 415, 416–417 summary of, 414 tiered storage solutions, 417–419 transforming for storage, 419–420 unprofitable data

…

, Justin, 67 L Last-mile monitoring, 476 Leadership. See also Management; Organizational design; Staffing for scalability. 360-degree reviews, 69 abuse of, 70 alignment with shareholder values, 74–75 born vs. made, 65 causal roadmap to success, 84–86 characteristics of, 66–67 compassion, 68 credibility, 70, 73 decision making, 73 definition

…

(Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence), 429 SETI@home project, 429 Sharding, definition, 311 Shards, definition, 311 Shared infrastructure, grid benefit, 457 Shareholder test, 24 Shareholder value, dilution by data cost, 415 Shareholder values, leadership alignment with, 74–75 ShareThis, case studies, 507–508 Slavery, abolition of, 80 Slivers, definition, 311 SMART (Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Realistic

How Boards Work: And How They Can Work Better in a Chaotic World

by Dambisa Moyo · 3 May 2021 · 272pp · 76,154 words

for bankruptcy. Leaving a good legacy is becoming harder, however, as the corporate board’s oversight role becomes ever more challenging and baseline notions about shareholder value and social responsibility shift with the changing times. Twenty-first-century companies are buffeted by unprecedented economic headwinds. Particularly after the onset of the coronavirus

…

more than 100 percent, and this placed pressure on boards and management teams across the banking sector to match the payouts of their competitors. Some shareholders value money today over investment for tomorrow. But picking one option over the other depends on a range of factors: Can the dividend be sustained? How

…

company establishes and maintains its reputation. As recent upheavals at Wells Fargo, WeWork, the Weinstein Company, and others have shown, culture directly affects profitability and shareholder value, and ultimately determines whether a company lives or dies. Headlines may give the impression that the cultural issues challenging corporations are purely the result of

…

to the transformation of the environment around them. For now, the law of the land is very clear: the true north for a company remains shareholder value. But things are changing, and in the years ahead there must be more focus on social and environmental concerns. The best boards are not waiting

The Last Tycoons: The Secret History of Lazard Frères & Co.

by William D. Cohan · 25 Dec 2015 · 1,009pp · 329,520 words

begin to lift the fog." To raised eyebrows, Bruce blamed Time Warner management for creating a "corporate inferno" that immolated at least $40 billion in shareholder value through a combination of, among other things, "bloated overhead" (evidenced by the company's new corporate headquarters at Columbus Circle and its fleet of corporate

House of Cards: A Tale of Hubris and Wretched Excess on Wall Street

by William D. Cohan · 15 Nov 2009 · 620pp · 214,639 words

a sale of the company—“with a focus on ensuring that we can handle and protect our customers well and at the same time maximize shareholder value.” Schwartz then opened up the call to questions and said he looked forward to speaking with everyone again on Monday for the earnings release. Guy

The Golden Passport: Harvard Business School, the Limits of Capitalism, and the Moral Failure of the MBA Elite

by Duff McDonald · 24 Apr 2017 · 827pp · 239,762 words

efficiency, he was implicitly sanctioning the idea that a company can be judged by a single metric. Today’s even more pernicious version of such: shareholder value. Writes Stewart: “The modern-day CEOs who sacrifice the long-term viability of their corporations for the sake of short-term boosts in their quarterly

…

Spar, corporations “are not institutions set up to be moral entities . . . they are institutions which really only have one mission, and that is to increase shareholder value.”4 Says who? Milton Friedman, obviously. But who else? Just a small sample of people who’ve actually “set up” corporations would seem to suggest

…

existed prior to 1970. And they would have found out that there still isn’t a single shred of empirical evidence that 100% focus on shareholder value to the exclusion of other societal factors actually produces measurably higher value for shareholders.” What’s truly unfortunate is that if one considers the work

…

was through, “any lingering doubt about the purpose of the corporation, or its commitment to various stakeholders, had been resolved. The corporation existed to create shareholder value; other commitments were means to that end.”7 “Business educators legitimized the notion that good management might mean dissolving the firm to improve shareholder return

…

purpose of a corporation is to produce goods and services for the benefit of society. When they graduate, they believe that it is to maximize shareholder value. John McArthur, then dean of HBS, liked Jensen’s message and invited him to HBS as a visiting professor in 1984. In The Intellectual Venture

…

, the longtime CEO of General Electric, eventually came around. In March 2009, he told the Financial Times, “On the face of it, shareholder value is the dumbest idea in the world. Shareholder value is a result, not a strategy . . . your main constituencies are your employees, your customers and your products. Managers and investors should

…

seem cartoonish, having flattened out man’s ability to balance competing objectives into his two-dimensional model of character. But to blame Jensen for the shareholder value revolution is to give him far more credit than he deserves. At most, Jensen served as nothing more than an instrument of intellectual violence. His

…

Capitalism” in a seminar centered on the work of Jensen. At that point, Lazonick was known to be a critic of Jensen’s ideas on shareholder value, but a critic in the academic sense—you sat across from each other on a podium during a seminar or you traded barbs in the

…

the administration for hiring him, but the faculty for not standing up to that which they knew was wrong. “Almost immediately after they hired him, shareholder value ideology quickly took a dominant position at HBS,” he recalls, “even though, from their own experience, the vast majority of faculty members did not believe

…

to that moment—the rise of “neoliberalism” and its emphasis on free markets and rejection of any government intervention in the economy; the triumph of “shareholder value” over managerial prerogative; and the underlying changes in the American economy itself, away from manufacturing toward services, and from industrialism to financialism—he argues that

…

learn about such things as corporate social responsibility than they don’t. And while it would be great if they learned alternatives to a pure shareholder value conception, having that curriculum won’t ensure that twenty years down the road, they will act any differently than if they hadn’t.”15 He

…

or she is “strategizing” about it or not—explicitly sets out to seek excess, or monopoly, profits. That’s wrong in the same way that shareholder value is wrong. While neat and tidy models may work in the classroom, in the real world, nobody makes decisions that way, and for any number

…

(shareholders, customers, and communities) and internal ones (employees and suppliers)—and then develop a strategy thereafter. “The stakeholder movement likely developed to counter the narrow shareholder value maximization view articulated by Milton Friedman and, subsequently, financial economists, such as Jensen,” he writes. “In this spirit, I believe the stakeholder helped us appreciate

…

. “Employee and process performance are critical for current and future success. Financial metrics, ultimately, will increase if companies’ performance improves. And to optimize long-term shareholder value, the firm had to internalize the preferences and expectations of its shareholders, customers, suppliers, employees, and communities. The key was to have a more robust

…

be laid at the foot of the Harvard Business School in this regard? Quite a bit. In their paper, “Corporate Malfeasance and the Myth of Shareholder Value,” Frank Dobbin and Dirk Zorn point to the shifting nexus of power of the nation’s business elite during the era. “If the classical view

…

saves his choicest criticism for others. “I guess you could say that takeover artists like Bill Ackman have contributed to the short-term orientation of shareholder value,” he says. “Now you have to beware of having too much cash on hand or not enough leverage. CEOs have been pushed into becoming very

…

losses in the stock.34 As Bloomberg’s Matt Levine pointed out, “[If] you wanted to create an imaginary company to illustrate the evils of shareholder value, you’d probably end up with something that looks a lot like Valeant. Tax inversion to Canada! Raising drug prices to exploit insurance! Cutting back

…

graduates. The closest they came to doing so was in 2006. That year, while sitting on a panel of scholars discussing whether the maximization of shareholder value was to blame for corporate malfeasance, Michael Jensen flat-out rejected the idea, saying, “There is no doubt that there have been many more incidents

…

to Michael Jensen. Michael Porter offers up a set of prescriptions for helping address an inequality that the School’s graduates—and its tilt toward shareholder value—helped create. When Jeff Skilling took the teachings of HBS too far, HBS declared that the way to avoid Enron happening all over again was

…

. 33David W. Ewing, Inside the Harvard Business School (New York: Crown, 1990), p. 29. 34Frank Dobbin and Dirk Zorn, “Corporate Malfeasance and the Myth of Shareholder Value,” SSRN Scholarly Paper, Rochester, NY, Social Science Research Network, 2005, http://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2412599. 35Kiechel, “New Debate About Harvard Business School,” p. 48

…

, 424; postwar surge in, 144; quantitative orientation of, 215–18, 220, 221, 224, 445; rankings, 254, 280, 493; risk management and, 551–52; shift to shareholder value/theory of the firm, 369; social responsibility and, 59, 369, 391; specialist curricula, 448; theory of business and, 57–58; tuition increases, 542; U.S

…

, 376, 380, 388, 390, 487, 538, 541, 542–43; as strategist in chief, 415–18. See also specific people “Corporate Malfeasance and the Myth of Shareholder Value” (Dobbin and Zorn), 462–63 “Corporate Power in the 21st Century” (Davis), 369 Corporate Strategy (Ansoff), 257–58 Corporation, The (Bakan), 362, 505 corporations, 8

…

, 430, 463; income inequality and, 56, 165–66, 463, 539, 544; inversions and tax avoidance, 529; investors as custodians, 366–67, 387, 388 (see also shareholder value); job turnover, 291, 383; under Kennedy, 28; labor unions and, 161; layoffs, 387, 492–93; Levitt’s redefining of identity, 261–62; MBAs in, 289

…

, 342, 385; price fixing, 285; profit motive and, 10, 367; Progressive containment of, 62; recruiters for, 151, 178, 186–87, 199, 207–8, 209, 460; shareholder value and, 10, 36, 360–64, 369, 418, 442, 462, 469, 491, 550, 567; shares in, 363, 375; short-term thinking, 247, 345, 443, 469, 551

…

, 410; Professorship of Business Ethics, 433; research areas of, 355–56; Retailing Group, 356; salary increase, 287; satisfaction of, 530; self-image of, 255–56; shareholder value ideology and, 377–78; Straus Professorship, 245; Taylorism and, 212; tenure, 279; Transportation Group, 356; turf war, 1960s, 286; weakness of, 356; William Ziegler Professor

…

; as Pareto’s elite, 113; postwar economic boom and, 170; professional manager and separation of ownership and control, 56; profitability and, 35, 145 (see also shareholder value); property rights ideology, 390; public confidence in, decline, 356; quantitative model, 117, 273–74, 365–82, 434, 450; Rockefeller on, 373; Roethlisberger and function of

…

Shaeffer, Charles, 106 Shames, Laurence, 168, 169–70, 172, 173–74, 177, 281, 435, 529 Shaping the Waves (Cruikshank), 324 Shapiro, Benson, 300, 332, 333 shareholder value/profit-driven management, 6, 10, 36, 298, 315, 360–64, 366, 418, 442–43, 454, 469, 491, 524, 550, 567 Shaw, Arch, 43, 47, 116

…

, 193; corporate layoffs (1990s) and, 492; crisis of 1907, 23; decline, American managers and, 342–52; distressed (1893–97), 23; early 1970s, 386; effect of shareholder value ideology, 372–73; federal regulation and, 102, 103, 108, 122, 131–32, 133, 200, 244, 347, 357, 358, 367, 385, 386–87, 430, 504–5

Value of Everything: An Antidote to Chaos The

by Mariana Mazzucato · 25 Apr 2018 · 457pp · 125,329 words

The Chairman's Lounge: The inside story of how Qantas sold us out

by Joe Aston · 27 Oct 2024 · 362pp · 130,141 words

Stakeholder Capitalism: A Global Economy That Works for Progress, People and Planet

by Klaus Schwab and Peter Vanham · 27 Jan 2021 · 460pp · 107,454 words

The Heart of Business: Leadership Principles for the Next Era of Capitalism

by Hubert Joly · 14 Jun 2021 · 265pp · 75,202 words

Too big to fail: the inside story of how Wall Street and Washington fought to save the financial system from crisis--and themselves

by Andrew Ross Sorkin · 15 Oct 2009 · 351pp · 102,379 words

The Inequality Puzzle: European and US Leaders Discuss Rising Income Inequality

by Roland Berger, David Grusky, Tobias Raffel, Geoffrey Samuels and Chris Wimer · 29 Oct 2010 · 237pp · 72,716 words

A Pelican Introduction Economics: A User's Guide

by Ha-Joon Chang · 26 May 2014 · 385pp · 111,807 words

Corporate Finance: Theory and Practice

by Pierre Vernimmen, Pascal Quiry, Maurizio Dallocchio, Yann le Fur and Antonio Salvi · 16 Oct 2017 · 1,544pp · 391,691 words

The Third Pillar: How Markets and the State Leave the Community Behind

by Raghuram Rajan · 26 Feb 2019 · 596pp · 163,682 words

Extreme Money: Masters of the Universe and the Cult of Risk

by Satyajit Das · 14 Oct 2011 · 741pp · 179,454 words

Investment Banking: Valuation, Leveraged Buyouts, and Mergers and Acquisitions

by Joshua Rosenbaum, Joshua Pearl and Joseph R. Perella · 18 May 2009 · 444pp · 86,565 words

Security Analysis

by Benjamin Graham and David Dodd · 1 Jan 1962 · 1,042pp · 266,547 words

The Investopedia Guide to Wall Speak: The Terms You Need to Know to Talk Like Cramer, Think Like Soros, and Buy Like Buffett

by Jack (edited By) Guinan · 27 Jul 2009 · 353pp · 88,376 words

The Firm

by Duff McDonald · 1 Jun 2014 · 654pp · 120,154 words

The Bank That Lived a Little: Barclays in the Age of the Very Free Market

by Philip Augar · 4 Jul 2018 · 457pp · 143,967 words

After the Music Stopped: The Financial Crisis, the Response, and the Work Ahead

by Alan S. Blinder · 24 Jan 2013 · 566pp · 155,428 words

The Shifts and the Shocks: What We've Learned--And Have Still to Learn--From the Financial Crisis

by Martin Wolf · 24 Nov 2015 · 524pp · 143,993 words

Valuation: Measuring and Managing the Value of Companies

by Tim Koller, McKinsey, Company Inc., Marc Goedhart, David Wessels, Barbara Schwimmer and Franziska Manoury · 16 Aug 2015 · 892pp · 91,000 words

The Finance Book: Understand the Numbers Even if You're Not a Finance Professional

by Stuart Warner and Si Hussain · 20 Apr 2017 · 439pp · 79,447 words

The Clash of the Cultures

by John C. Bogle · 30 Jun 2012 · 339pp · 109,331 words

Money Changes Everything: How Finance Made Civilization Possible

by William N. Goetzmann · 11 Apr 2016 · 695pp · 194,693 words

Mastering Private Equity

by Zeisberger, Claudia,Prahl, Michael,White, Bowen, Michael Prahl and Bowen White · 15 Jun 2017

Stolen: How to Save the World From Financialisation

by Grace Blakeley · 9 Sep 2019 · 263pp · 80,594 words

Trading and Exchanges: Market Microstructure for Practitioners

by Larry Harris · 2 Jan 2003 · 1,164pp · 309,327 words

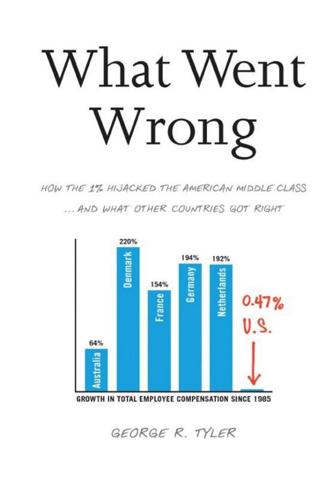

What Went Wrong: How the 1% Hijacked the American Middle Class . . . And What Other Countries Got Right

by George R. Tyler · 15 Jul 2013 · 772pp · 203,182 words

Guide to business modelling

by John Tennent, Graham Friend and Economist Group · 15 Dec 2005 · 287pp · 44,739 words

The Finance Curse: How Global Finance Is Making Us All Poorer

by Nicholas Shaxson · 10 Oct 2018 · 482pp · 149,351 words

The Greed Merchants: How the Investment Banks Exploited the System

by Philip Augar · 20 Apr 2005 · 290pp · 83,248 words

The Bankers' New Clothes: What's Wrong With Banking and What to Do About It

by Anat Admati and Martin Hellwig · 15 Feb 2013 · 726pp · 172,988 words

Throwing Rocks at the Google Bus: How Growth Became the Enemy of Prosperity

by Douglas Rushkoff · 1 Mar 2016 · 366pp · 94,209 words

Principles of Corporate Finance

by Richard A. Brealey, Stewart C. Myers and Franklin Allen · 15 Feb 2014

The Global Auction: The Broken Promises of Education, Jobs, and Incomes

by Phillip Brown, Hugh Lauder and David Ashton · 3 Nov 2010 · 209pp · 80,086 words

The Man Who Broke Capitalism: How Jack Welch Gutted the Heartland and Crushed the Soul of Corporate America—and How to Undo His Legacy

by David Gelles · 30 May 2022 · 318pp · 91,957 words

MONEY Master the Game: 7 Simple Steps to Financial Freedom

by Tony Robbins · 18 Nov 2014 · 825pp · 228,141 words

Big Business: A Love Letter to an American Anti-Hero

by Tyler Cowen · 8 Apr 2019 · 297pp · 84,009 words

The Unusual Billionaires

by Saurabh Mukherjea · 16 Aug 2016

Tomorrow's Capitalist: My Search for the Soul of Business

by Alan Murray · 15 Dec 2022 · 263pp · 77,786 words

Dear Chairman: Boardroom Battles and the Rise of Shareholder Activism

by Jeff Gramm · 23 Feb 2016 · 384pp · 103,658 words

Triumph of the Yuppies: America, the Eighties, and the Creation of an Unequal Nation

by Tom McGrath · 3 Jun 2024 · 326pp · 103,034 words

The Devil's Derivatives: The Untold Story of the Slick Traders and Hapless Regulators Who Almost Blew Up Wall Street . . . And Are Ready to Do It Again

by Nicholas Dunbar · 11 Jul 2011 · 350pp · 103,270 words

Wall Street: How It Works And for Whom

by Doug Henwood · 30 Aug 1998 · 586pp · 159,901 words

Reimagining Capitalism in a World on Fire

by Rebecca Henderson · 27 Apr 2020 · 330pp · 99,044 words

More Than You Know: Finding Financial Wisdom in Unconventional Places (Updated and Expanded)

by Michael J. Mauboussin · 1 Jan 2006 · 348pp · 83,490 words

Free Market Missionaries: The Corporate Manipulation of Community Values

by Sharon Beder · 30 Sep 2006 · 273pp · 34,920 words

What Happened to Goldman Sachs: An Insider's Story of Organizational Drift and Its Unintended Consequences

by Steven G. Mandis · 9 Sep 2013 · 413pp · 117,782 words

Barbarians at the Gate: The Fall of RJR Nabisco

by Bryan Burrough and John Helyar · 1 Jan 1990 · 713pp · 203,688 words

The Myth of the Rational Market: A History of Risk, Reward, and Delusion on Wall Street

by Justin Fox · 29 May 2009 · 461pp · 128,421 words

The Lost Bank: The Story of Washington Mutual-The Biggest Bank Failure in American History

by Kirsten Grind · 11 Jun 2012 · 549pp · 147,112 words

Creative Intelligence: Harnessing the Power to Create, Connect, and Inspire

by Bruce Nussbaum · 5 Mar 2013 · 385pp · 101,761 words

Unconventional Success: A Fundamental Approach to Personal Investment

by David F. Swensen · 8 Aug 2005 · 490pp · 117,629 words

Secrets of Sand Hill Road: Venture Capital and How to Get It

by Scott Kupor · 3 Jun 2019 · 340pp · 100,151 words

Stocks for the Long Run 5/E: the Definitive Guide to Financial Market Returns & Long-Term Investment Strategies

by Jeremy Siegel · 7 Jan 2014 · 517pp · 139,477 words

Oil: Money, Politics, and Power in the 21st Century

by Tom Bower · 1 Jan 2009 · 554pp · 168,114 words

Financial Statement Analysis: A Practitioner's Guide

by Martin S. Fridson and Fernando Alvarez · 31 May 2011

file:///C:/Documents%20and%...

by vpavan

Pour Your Heart Into It: How Starbucks Built a Company One Cup at a Time

by Howard Schultz and Dori Jones Yang

People, Power, and Profits: Progressive Capitalism for an Age of Discontent

by Joseph E. Stiglitz · 22 Apr 2019 · 462pp · 129,022 words

Americana: A 400-Year History of American Capitalism

by Bhu Srinivasan · 25 Sep 2017 · 801pp · 209,348 words

Brave New Work: Are You Ready to Reinvent Your Organization?

by Aaron Dignan · 1 Feb 2019 · 309pp · 81,975 words

The Crux

by Richard Rumelt · 27 Apr 2022 · 363pp · 109,834 words

Deep Value

by Tobias E. Carlisle · 19 Aug 2014

King Icahn: The Biography of a Renegade Capitalist

by Mark Stevens · 31 May 1993 · 414pp · 108,413 words

The Enlightened Capitalists

by James O'Toole · 29 Dec 2018 · 716pp · 192,143 words

Age of Greed: The Triumph of Finance and the Decline of America, 1970 to the Present

by Jeff Madrick · 11 Jun 2012 · 840pp · 202,245 words

Economists and the Powerful

by Norbert Haring, Norbert H. Ring and Niall Douglas · 30 Sep 2012 · 261pp · 103,244 words

The System: Who Rigged It, How We Fix It

by Robert B. Reich · 24 Mar 2020 · 154pp · 47,880 words

How the City Really Works: The Definitive Guide to Money and Investing in London's Square Mile

by Alexander Davidson · 1 Apr 2008 · 368pp · 32,950 words

Lessons from the Titans: What Companies in the New Economy Can Learn from the Great Industrial Giants to Drive Sustainable Success

by Scott Davis, Carter Copeland and Rob Wertheimer · 13 Jul 2020 · 372pp · 101,678 words

Capitalism Without Capital: The Rise of the Intangible Economy

by Jonathan Haskel and Stian Westlake · 7 Nov 2017 · 346pp · 89,180 words

What They Do With Your Money: How the Financial System Fails Us, and How to Fix It

by Stephen Davis, Jon Lukomnik and David Pitt-Watson · 30 Apr 2016 · 304pp · 80,965 words

Stocks for the Long Run, 4th Edition: The Definitive Guide to Financial Market Returns & Long Term Investment Strategies

by Jeremy J. Siegel · 18 Dec 2007

One Up on Wall Street

by Peter Lynch · 11 May 2012

Ethics in Investment Banking

by John N. Reynolds and Edmund Newell · 8 Nov 2011 · 193pp · 11,060 words

Makers and Takers: The Rise of Finance and the Fall of American Business

by Rana Foroohar · 16 May 2016 · 515pp · 132,295 words

Tailspin: The People and Forces Behind America's Fifty-Year Fall--And Those Fighting to Reverse It

by Steven Brill · 28 May 2018 · 519pp · 155,332 words

Conscious Capitalism, With a New Preface by the Authors: Liberating the Heroic Spirit of Business

by John Mackey, Rajendra Sisodia and Bill George · 7 Jan 2014 · 335pp · 104,850 words

Other People's Money: Masters of the Universe or Servants of the People?

by John Kay · 2 Sep 2015 · 478pp · 126,416 words

Culture and Prosperity: The Truth About Markets - Why Some Nations Are Rich but Most Remain Poor

by John Kay · 24 May 2004 · 436pp · 76 words

Value Investing: From Graham to Buffett and Beyond

by Bruce C. N. Greenwald, Judd Kahn, Paul D. Sonkin and Michael van Biema · 26 Jan 2004 · 306pp · 97,211 words

The Money Machine: How the City Works

by Philip Coggan · 1 Jul 2009 · 253pp · 79,214 words

Them And Us: Politics, Greed And Inequality - Why We Need A Fair Society

by Will Hutton · 30 Sep 2010 · 543pp · 147,357 words

WTF?: What's the Future and Why It's Up to Us

by Tim O'Reilly · 9 Oct 2017 · 561pp · 157,589 words

Economic Dignity

by Gene Sperling · 14 Sep 2020 · 667pp · 149,811 words

The Cost of Inequality: Why Economic Equality Is Essential for Recovery

by Stewart Lansley · 19 Jan 2012 · 223pp · 10,010 words

The Investment Checklist: The Art of In-Depth Research

by Michael Shearn · 8 Nov 2011 · 400pp · 124,678 words

Stakeholder Capitalism: A Global Economy That Works for Progress, People and Planet

by Klaus Schwab · 7 Jan 2021 · 460pp · 107,454 words

Concentrated Investing

by Allen C. Benello · 7 Dec 2016

Collision Course: Carlos Ghosn and the Culture Wars That Upended an Auto Empire

by Hans Gremeil and William Sposato · 15 Dec 2021 · 404pp · 126,447 words

The Price of Time: The Real Story of Interest

by Edward Chancellor · 15 Aug 2022 · 829pp · 187,394 words

Our Lives in Their Portfolios: Why Asset Managers Own the World

by Brett Chistophers · 25 Apr 2023 · 404pp · 106,233 words

The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power

by Daniel Yergin · 23 Dec 2008 · 1,445pp · 469,426 words

Traders, Guns & Money: Knowns and Unknowns in the Dazzling World of Derivatives

by Satyajit Das · 15 Nov 2006 · 349pp · 134,041 words

The Price of Inequality: How Today's Divided Society Endangers Our Future

by Joseph E. Stiglitz · 10 Jun 2012 · 580pp · 168,476 words

Who Stole the American Dream?

by Hedrick Smith · 10 Sep 2012 · 598pp · 172,137 words

Bill Marriott: Success Is Never Final--His Life and the Decisions That Built a Hotel Empire

by Dale van Atta · 14 Aug 2019 · 520pp · 164,834 words

Making It Happen: Fred Goodwin, RBS and the Men Who Blew Up the British Economy

by Iain Martin · 11 Sep 2013 · 387pp · 119,244 words

Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking of America: A Recent History

by Kurt Andersen · 14 Sep 2020 · 486pp · 150,849 words

Obliquity: Why Our Goals Are Best Achieved Indirectly

by John Kay · 30 Apr 2010 · 237pp · 50,758 words

Risk Management in Trading

by Davis Edwards · 10 Jul 2014

The Snowball: Warren Buffett and the Business of Life

by Alice Schroeder · 1 Sep 2008 · 1,336pp · 415,037 words

Capitalism 4.0: The Birth of a New Economy in the Aftermath of Crisis

by Anatole Kaletsky · 22 Jun 2010 · 484pp · 136,735 words

The Age of Surveillance Capitalism

by Shoshana Zuboff · 15 Jan 2019 · 918pp · 257,605 words

Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist

by Kate Raworth · 22 Mar 2017 · 403pp · 111,119 words

The Decline and Fall of IBM: End of an American Icon?

by Robert X. Cringely · 1 Jun 2014 · 232pp · 71,024 words

Efficiently Inefficient: How Smart Money Invests and Market Prices Are Determined

by Lasse Heje Pedersen · 12 Apr 2015 · 504pp · 139,137 words

The End of Accounting and the Path Forward for Investors and Managers (Wiley Finance)

by Feng Gu · 26 Jun 2016

Rethinking Capitalism: Economics and Policy for Sustainable and Inclusive Growth

by Michael Jacobs and Mariana Mazzucato · 31 Jul 2016 · 370pp · 102,823 words

Toward Rational Exuberance: The Evolution of the Modern Stock Market

by B. Mark Smith · 1 Jan 2001 · 403pp · 119,206 words

The Corporation: The Pathological Pursuit of Profit and Power

by Joel Bakan · 1 Jan 2003

Radical Markets: Uprooting Capitalism and Democracy for a Just Society

by Eric Posner and E. Weyl · 14 May 2018 · 463pp · 105,197 words

Rewriting the Rules of the European Economy: An Agenda for Growth and Shared Prosperity

by Joseph E. Stiglitz · 28 Jan 2020 · 408pp · 108,985 words

Private Empire: ExxonMobil and American Power

by Steve Coll · 30 Apr 2012 · 944pp · 243,883 words

The Zero Marginal Cost Society: The Internet of Things, the Collaborative Commons, and the Eclipse of Capitalism

by Jeremy Rifkin · 31 Mar 2014 · 565pp · 151,129 words

The Four: How Amazon, Apple, Facebook, and Google Divided and Conquered the World

by Scott Galloway · 2 Oct 2017 · 305pp · 79,303 words

Finance and the Good Society

by Robert J. Shiller · 1 Jan 2012 · 288pp · 16,556 words

Samsung Rising: The Inside Story of the South Korean Giant That Set Out to Beat Apple and Conquer Tech

by Geoffrey Cain · 15 Mar 2020 · 540pp · 119,731 words

Start With Why: How Great Leaders Inspire Everyone to Take Action

by Simon Sinek · 29 Oct 2009 · 261pp · 79,883 words

Chokepoint Capitalism

by Rebecca Giblin and Cory Doctorow · 26 Sep 2022 · 396pp · 113,613 words

Palace Coup: The Billionaire Brawl Over the Bankrupt Caesars Gaming Empire

by Sujeet Indap and Max Frumes · 16 Mar 2021 · 362pp · 116,497 words

American Foundations: An Investigative History

by Mark Dowie · 3 Oct 2009 · 410pp · 115,666 words

Unscripted: The Epic Battle for a Media Empire and the Redstone Family Legacy

by James B Stewart and Rachel Abrams · 14 Feb 2023 · 521pp · 136,802 words

This Could Be Our Future: A Manifesto for a More Generous World

by Yancey Strickler · 29 Oct 2019 · 254pp · 61,387 words

The Raging 2020s: Companies, Countries, People - and the Fight for Our Future

by Alec Ross · 13 Sep 2021 · 363pp · 109,077 words

May Contain Lies: How Stories, Statistics, and Studies Exploit Our Biases—And What We Can Do About It

by Alex Edmans · 13 May 2024 · 315pp · 87,035 words

Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism

by Anne Case and Angus Deaton · 17 Mar 2020 · 421pp · 110,272 words

Nothing but Net: 10 Timeless Stock-Picking Lessons From One of Wall Street’s Top Tech Analysts

by Mark Mahaney · 9 Nov 2021 · 311pp · 90,172 words

The Outsiders: Eight Unconventional CEOs and Their Radically Rational Blueprint for Success

by William Thorndike · 14 Sep 2012 · 330pp · 59,335 words

What If We Get It Right?: Visions of Climate Futures

by Ayana Elizabeth Johnson · 17 Sep 2024 · 588pp · 160,825 words

The Power Law: Venture Capital and the Making of the New Future

by Sebastian Mallaby · 1 Feb 2022 · 935pp · 197,338 words

Radical Uncertainty: Decision-Making for an Unknowable Future

by Mervyn King and John Kay · 5 Mar 2020 · 807pp · 154,435 words

The New Tycoons: Inside the Trillion Dollar Private Equity Industry That Owns Everything

by Jason Kelly · 10 Sep 2012 · 274pp · 81,008 words

Green Swans: The Coming Boom in Regenerative Capitalism

by John Elkington · 6 Apr 2020 · 384pp · 93,754 words

All the Money in the World

by Peter W. Bernstein · 17 Dec 2008 · 538pp · 147,612 words

The Job: The Future of Work in the Modern Era

by Ellen Ruppel Shell · 22 Oct 2018 · 402pp · 126,835 words

The Intelligent Investor (Collins Business Essentials)

by Benjamin Graham and Jason Zweig · 1 Jan 1949 · 670pp · 194,502 words

Profiting Without Producing: How Finance Exploits Us All

by Costas Lapavitsas · 14 Aug 2013 · 554pp · 158,687 words

All the Devils Are Here

by Bethany McLean · 19 Oct 2010 · 543pp · 157,991 words

The Future of Capitalism: Facing the New Anxieties

by Paul Collier · 4 Dec 2018 · 310pp · 85,995 words

Future Perfect: The Case for Progress in a Networked Age

by Steven Johnson · 14 Jul 2012 · 184pp · 53,625 words

Den of Thieves

by James B. Stewart · 14 Oct 1991 · 706pp · 206,202 words

The Connected Company

by Dave Gray and Thomas Vander Wal · 2 Dec 2014 · 372pp · 89,876 words

Why We Can't Afford the Rich

by Andrew Sayer · 6 Nov 2014 · 504pp · 143,303 words

Confessions of a Wall Street Analyst: A True Story of Inside Information and Corruption in the Stock Market

by Daniel Reingold and Jennifer Reingold · 1 Jan 2006 · 506pp · 146,607 words

The Myth of Capitalism: Monopolies and the Death of Competition

by Jonathan Tepper · 20 Nov 2018 · 417pp · 97,577 words

Strategy: A History

by Lawrence Freedman · 31 Oct 2013 · 1,073pp · 314,528 words

Woke, Inc: Inside Corporate America's Social Justice Scam

by Vivek Ramaswamy · 16 Aug 2021 · 344pp · 104,522 words

Working Backwards: Insights, Stories, and Secrets From Inside Amazon

by Colin Bryar and Bill Carr · 9 Feb 2021 · 302pp · 100,493 words

Cable Cowboy

by Mark Robichaux · 19 Oct 2002

The Triumph of Injustice: How the Rich Dodge Taxes and How to Make Them Pay

by Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman · 14 Oct 2019 · 232pp · 70,361 words

When McKinsey Comes to Town: The Hidden Influence of the World's Most Powerful Consulting Firm

by Walt Bogdanich and Michael Forsythe · 3 Oct 2022 · 689pp · 134,457 words

Vulture Capitalism: Corporate Crimes, Backdoor Bailouts, and the Death of Freedom

by Grace Blakeley · 11 Mar 2024 · 371pp · 137,268 words

The End of the Free Market: Who Wins the War Between States and Corporations?

by Ian Bremmer · 12 May 2010 · 247pp · 68,918 words

Financial Market Meltdown: Everything You Need to Know to Understand and Survive the Global Credit Crisis

by Kevin Mellyn · 30 Sep 2009 · 225pp · 11,355 words

The Code of Capital: How the Law Creates Wealth and Inequality

by Katharina Pistor · 27 May 2019 · 316pp · 117,228 words

The Color of Money: Black Banks and the Racial Wealth Gap

by Mehrsa Baradaran · 14 Sep 2017 · 520pp · 153,517 words

Competition Overdose: How Free Market Mythology Transformed Us From Citizen Kings to Market Servants

by Maurice E. Stucke and Ariel Ezrachi · 14 May 2020 · 511pp · 132,682 words

Power and Progress: Our Thousand-Year Struggle Over Technology and Prosperity

by Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson · 15 May 2023 · 619pp · 177,548 words

The Acquirer's Multiple: How the Billionaire Contrarians of Deep Value Beat the Market

by Tobias E. Carlisle · 13 Oct 2017 · 120pp · 33,892 words

The Quest: Energy, Security, and the Remaking of the Modern World

by Daniel Yergin · 14 May 2011 · 1,373pp · 300,577 words

After the New Economy: The Binge . . . And the Hangover That Won't Go Away

by Doug Henwood · 9 May 2005 · 306pp · 78,893 words

The Little Book That Builds Wealth: The Knockout Formula for Finding Great Investments

by Pat Dorsey · 1 Mar 2008 · 141pp · 40,979 words

Capitalism: Money, Morals and Markets

by John Plender · 27 Jul 2015 · 355pp · 92,571 words

Celebration of Fools: An Inside Look at the Rise and Fall of JCPenney

by Bill Hare · 30 May 2004 · 352pp · 96,692 words

The Coke Machine: The Dirty Truth Behind the World's Favorite Soft Drink

by Michael Blanding · 14 Jun 2010 · 385pp · 133,839 words

Understanding Asset Allocation: An Intuitive Approach to Maximizing Your Portfolio

by Victor A. Canto · 2 Jan 2005 · 337pp · 89,075 words

Mythology of Work: How Capitalism Persists Despite Itself

by Peter Fleming · 14 Jun 2015 · 320pp · 86,372 words

Dual Transformation: How to Reposition Today's Business While Creating the Future

by Scott D. Anthony and Mark W. Johnson · 27 Mar 2017 · 293pp · 78,439 words

The Economics Anti-Textbook: A Critical Thinker's Guide to Microeconomics

by Rod Hill and Anthony Myatt · 15 Mar 2010

Treasure Islands: Uncovering the Damage of Offshore Banking and Tax Havens

by Nicholas Shaxson · 11 Apr 2011 · 429pp · 120,332 words

Masters of Management: How the Business Gurus and Their Ideas Have Changed the World—for Better and for Worse

by Adrian Wooldridge · 29 Nov 2011 · 460pp · 131,579 words

Finding Alphas: A Quantitative Approach to Building Trading Strategies

by Igor Tulchinsky · 30 Sep 2019 · 321pp

Still Broke: Walmart's Remarkable Transformation and the Limits of Socially Conscious Capitalism

by Rick Wartzman · 15 Nov 2022 · 215pp · 69,370 words

Vassal State

by Angus Hanton · 25 Mar 2024 · 277pp · 81,718 words

The Alternative: How to Build a Just Economy

by Nick Romeo · 15 Jan 2024 · 343pp · 103,376 words

Are Chief Executives Overpaid?

by Deborah Hargreaves · 29 Nov 2018 · 98pp · 27,201 words

23 Things They Don't Tell You About Capitalism

by Ha-Joon Chang · 1 Jan 2010 · 365pp · 88,125 words

Car Guys vs. Bean Counters: The Battle for the Soul of American Business

by Bob Lutz · 31 May 2011 · 249pp · 73,731 words

Transaction Man: The Rise of the Deal and the Decline of the American Dream

by Nicholas Lemann · 9 Sep 2019 · 354pp · 118,970 words

Broken Markets: A User's Guide to the Post-Finance Economy

by Kevin Mellyn · 18 Jun 2012 · 183pp · 17,571 words

Bezonomics: How Amazon Is Changing Our Lives and What the World's Best Companies Are Learning From It

by Brian Dumaine · 11 May 2020 · 411pp · 98,128 words

Triumph of the Optimists: 101 Years of Global Investment Returns

by Elroy Dimson, Paul Marsh and Mike Staunton · 3 Feb 2002 · 353pp · 148,895 words

The Great Demographic Reversal: Ageing Societies, Waning Inequality, and an Inflation Revival

by Charles Goodhart and Manoj Pradhan · 8 Aug 2020 · 438pp · 84,256 words

The Impulse Society: America in the Age of Instant Gratification

by Paul Roberts · 1 Sep 2014 · 324pp · 92,805 words

The Default Line: The Inside Story of People, Banks and Entire Nations on the Edge

by Faisal Islam · 28 Aug 2013 · 475pp · 155,554 words

How to Speak Money: What the Money People Say--And What It Really Means

by John Lanchester · 5 Oct 2014 · 261pp · 86,905 words

Frugal Innovation: How to Do Better With Less

by Jaideep Prabhu Navi Radjou · 15 Feb 2015 · 400pp · 88,647 words

The Second Curve: Thoughts on Reinventing Society

by Charles Handy · 12 Mar 2015 · 164pp · 57,068 words

Street Fighters: The Last 72 Hours of Bear Stearns, the Toughest Firm on Wall Street

by Kate Kelly · 14 Apr 2009 · 258pp · 71,880 words

Startup CEO: A Field Guide to Scaling Up Your Business, + Website

by Matt Blumberg · 13 Aug 2013 · 561pp · 114,843 words

Lab Rats: How Silicon Valley Made Work Miserable for the Rest of Us

by Dan Lyons · 22 Oct 2018 · 252pp · 78,780 words

SUPERHUBS: How the Financial Elite and Their Networks Rule Our World

by Sandra Navidi · 24 Jan 2017 · 831pp · 98,409 words

Red-Blooded Risk: The Secret History of Wall Street

by Aaron Brown and Eric Kim · 10 Oct 2011 · 483pp · 141,836 words

Women Leaders at Work: Untold Tales of Women Achieving Their Ambitions

by Elizabeth Ghaffari · 5 Dec 2011 · 493pp · 139,845 words

Modernising Money: Why Our Monetary System Is Broken and How It Can Be Fixed

by Andrew Jackson (economist) and Ben Dyson (economist) · 15 Nov 2012 · 363pp · 107,817 words

Philanthrocapitalism

by Matthew Bishop, Michael Green and Bill Clinton · 29 Sep 2008 · 401pp · 115,959 words

Quantitative Value: A Practitioner's Guide to Automating Intelligent Investment and Eliminating Behavioral Errors

by Wesley R. Gray and Tobias E. Carlisle · 29 Nov 2012 · 263pp · 75,455 words

We the Corporations: How American Businesses Won Their Civil Rights

by Adam Winkler · 27 Feb 2018 · 581pp · 162,518 words

Quality Investing: Owning the Best Companies for the Long Term

by Torkell T. Eide, Lawrence A. Cunningham and Patrick Hargreaves · 5 Jan 2016 · 178pp · 52,637 words

Competition Demystified

by Bruce C. Greenwald · 31 Aug 2016 · 482pp · 125,973 words

Built on a Lie: The Rise and Fall of Neil Woodford and the Fate of Middle England’s Money

by Owen Walker · 4 Mar 2021 · 278pp · 82,771 words

Sabotage: The Financial System's Nasty Business

by Anastasia Nesvetailova and Ronen Palan · 28 Jan 2020 · 218pp · 62,889 words

Restarting the Future: How to Fix the Intangible Economy

by Jonathan Haskel and Stian Westlake · 4 Apr 2022 · 338pp · 85,566 words

Bad Company

by Megan Greenwell · 18 Apr 2025 · 385pp · 103,818 words

The Meritocracy Trap: How America's Foundational Myth Feeds Inequality, Dismantles the Middle Class, and Devours the Elite

by Daniel Markovits · 14 Sep 2019 · 976pp · 235,576 words

The Smartest Guys in the Room

by Bethany McLean · 25 Nov 2013 · 778pp · 233,096 words

Character Limit: How Elon Musk Destroyed Twitter

by Kate Conger and Ryan Mac · 17 Sep 2024

Flying Blind: The 737 MAX Tragedy and the Fall of Boeing

by Peter Robison · 29 Nov 2021 · 382pp · 105,657 words

100 Baggers: Stocks That Return 100-To-1 and How to Find Them

by Christopher W Mayer · 21 May 2018

The Everything Store: Jeff Bezos and the Age of Amazon

by Brad Stone · 14 Oct 2013 · 380pp · 118,675 words

The Boom: How Fracking Ignited the American Energy Revolution and Changed the World

by Russell Gold · 7 Apr 2014 · 423pp · 118,002 words

Reinventing Organizations: A Guide to Creating Organizations Inspired by the Next Stage of Human Consciousness

by Frederic Laloux and Ken Wilber · 9 Feb 2014 · 436pp · 141,321 words

A Demon of Our Own Design: Markets, Hedge Funds, and the Perils of Financial Innovation

by Richard Bookstaber · 5 Apr 2007 · 289pp · 113,211 words

Winners Take All: The Elite Charade of Changing the World

by Anand Giridharadas · 27 Aug 2018 · 296pp · 98,018 words

Made to Stick: Why Some Ideas Survive and Others Die

by Chip Heath and Dan Heath · 18 Dec 2006 · 313pp · 94,490 words

Global Spin: The Corporate Assault on Environmentalism

by Sharon Beder · 1 Jan 1997 · 651pp · 161,270 words

In Pursuit of the Perfect Portfolio: The Stories, Voices, and Key Insights of the Pioneers Who Shaped the Way We Invest

by Andrew W. Lo and Stephen R. Foerster · 16 Aug 2021 · 542pp · 145,022 words

Rethinking the Economics of Land and Housing

by Josh Ryan-Collins, Toby Lloyd and Laurie Macfarlane · 28 Feb 2017 · 346pp · 90,371 words

Power, for All: How It Really Works and Why It's Everyone's Business

by Julie Battilana and Tiziana Casciaro · 30 Aug 2021 · 345pp · 92,063 words

The Great Disruption: Why the Climate Crisis Will Bring on the End of Shopping and the Birth of a New World

by Paul Gilding · 28 Mar 2011 · 337pp · 103,273 words

How Money Became Dangerous

by Christopher Varelas · 15 Oct 2019 · 477pp · 144,329 words

Aiming High: Masayoshi Son, SoftBank, and Disrupting Silicon Valley

by Atsuo Inoue · 18 Nov 2021 · 295pp · 89,441 words

The Great Tax Robbery: How Britain Became a Tax Haven for Fat Cats and Big Business

by Richard Brooks · 2 Jan 2014 · 301pp · 88,082 words

System Error: Where Big Tech Went Wrong and How We Can Reboot

by Rob Reich, Mehran Sahami and Jeremy M. Weinstein · 6 Sep 2021

Super Pumped: The Battle for Uber

by Mike Isaac · 2 Sep 2019 · 444pp · 127,259 words

The Verdict: Did Labour Change Britain?

by Polly Toynbee and David Walker · 6 Oct 2011 · 471pp · 109,267 words

Panderer to Power

by Frederick Sheehan · 21 Oct 2009 · 435pp · 127,403 words

Joel on Software

by Joel Spolsky · 1 Aug 2004 · 370pp · 105,085 words

The Cheating Culture: Why More Americans Are Doing Wrong to Get Ahead

by David Callahan · 1 Jan 2004 · 452pp · 110,488 words

I.O.U.: Why Everyone Owes Everyone and No One Can Pay

by John Lanchester · 14 Dec 2009 · 322pp · 77,341 words

How Markets Fail: The Logic of Economic Calamities

by John Cassidy · 10 Nov 2009 · 545pp · 137,789 words

House of Debt: How They (And You) Caused the Great Recession, and How We Can Prevent It From Happening Again

by Atif Mian and Amir Sufi · 11 May 2014 · 249pp · 66,383 words

Everything for Everyone: The Radical Tradition That Is Shaping the Next Economy

by Nathan Schneider · 10 Sep 2018 · 326pp · 91,559 words

The Entrepreneurial State: Debunking Public vs. Private Sector Myths

by Mariana Mazzucato · 1 Jan 2011 · 382pp · 92,138 words

Mastering the VC Game: A Venture Capital Insider Reveals How to Get From Start-Up to IPO on Your Terms

by Jeffrey Bussgang · 31 Mar 2010 · 253pp · 65,834 words

The Paypal Wars: Battles With Ebay, the Media, the Mafia, and the Rest of Planet Earth

by Eric M. Jackson · 15 Jan 2004 · 398pp · 108,889 words

A Failure of Capitalism: The Crisis of '08 and the Descent Into Depression

by Richard A. Posner · 30 Apr 2009 · 305pp · 69,216 words

Execution: The Discipline of Getting Things Done

by Larry Bossidy · 10 Nov 2009 · 244pp · 76,192 words

Superclass: The Global Power Elite and the World They Are Making

by David Rothkopf · 18 Mar 2008 · 535pp · 158,863 words

Double Entry: How the Merchants of Venice Shaped the Modern World - and How Their Invention Could Make or Break the Planet

by Jane Gleeson-White · 14 May 2011 · 274pp · 66,721 words

The Smartphone Society

by Nicole Aschoff

The King of Content: Sumner Redstone's Battle for Viacom, CBS, and Everlasting Control of His Media Empire

by Keach Hagey · 25 Jun 2018 · 499pp · 131,113 words

Battle for the Bird: Jack Dorsey, Elon Musk, and the $44 Billion Fight for Twitter's Soul

by Kurt Wagner · 20 Feb 2024 · 332pp · 127,754 words

Enshittification: Why Everything Suddenly Got Worse and What to Do About It

by Cory Doctorow · 6 Oct 2025 · 313pp · 94,415 words

Peers Inc: How People and Platforms Are Inventing the Collaborative Economy and Reinventing Capitalism

by Robin Chase · 14 May 2015 · 330pp · 91,805 words

The Accidental Investment Banker: Inside the Decade That Transformed Wall Street

by Jonathan A. Knee · 31 Jul 2006 · 362pp · 108,359 words

The Founders: The Story of Paypal and the Entrepreneurs Who Shaped Silicon Valley

by Jimmy Soni · 22 Feb 2022 · 505pp · 161,581 words

MacroWikinomics: Rebooting Business and the World

by Don Tapscott and Anthony D. Williams · 28 Sep 2010 · 552pp · 168,518 words

Money Mavericks: Confessions of a Hedge Fund Manager

by Lars Kroijer · 26 Jul 2010 · 244pp · 79,044 words

Winner-Take-All Politics: How Washington Made the Rich Richer-And Turned Its Back on the Middle Class

by Paul Pierson and Jacob S. Hacker · 14 Sep 2010 · 602pp · 120,848 words

Competing on Analytics: The New Science of Winning

by Thomas H. Davenport and Jeanne G. Harris · 6 Mar 2007 · 233pp · 67,596 words

The Code: Silicon Valley and the Remaking of America

by Margaret O'Mara · 8 Jul 2019

Sickening: How Big Pharma Broke American Health Care and How We Can Repair It

by John Abramson · 15 Dec 2022 · 362pp · 97,473 words

Abolish Silicon Valley: How to Liberate Technology From Capitalism

by Wendy Liu · 22 Mar 2020 · 223pp · 71,414 words

The Success Equation: Untangling Skill and Luck in Business, Sports, and Investing

by Michael J. Mauboussin · 14 Jul 2012 · 299pp · 92,782 words

Netflixed: The Epic Battle for America's Eyeballs

by Gina Keating · 10 Oct 2012 · 347pp · 91,318 words

How I Became a Quant: Insights From 25 of Wall Street's Elite

by Richard R. Lindsey and Barry Schachter · 30 Jun 2007

Lessons From Private Equity Any Company Can Use

by Orit Gadiesh and Hugh MacArthur · 14 Aug 2008 · 92pp · 23,741 words

Decisive: How to Make Better Choices in Life and Work

by Chip Heath and Dan Heath · 26 Mar 2013 · 316pp · 94,886 words

Swimming With Sharks: My Journey into the World of the Bankers

by Joris Luyendijk · 14 Sep 2015 · 257pp · 71,686 words

Buying Time: The Delayed Crisis of Democratic Capitalism

by Wolfgang Streeck · 1 Jan 2013 · 353pp · 81,436 words

The Fissured Workplace

by David Weil · 17 Feb 2014 · 518pp · 147,036 words

The Making of Global Capitalism

by Leo Panitch and Sam Gindin · 8 Oct 2012 · 823pp · 206,070 words

The Wrecking Crew: How Conservatives Rule

by Thomas Frank · 5 Aug 2008 · 482pp · 122,497 words

Blitzscaling: The Lightning-Fast Path to Building Massively Valuable Companies

by Reid Hoffman and Chris Yeh · 14 Apr 2018 · 286pp · 87,401 words

The Rise of the Quants: Marschak, Sharpe, Black, Scholes and Merton

by Colin Read · 16 Jul 2012 · 206pp · 70,924 words

Overhaul: An Insider's Account of the Obama Administration's Emergency Rescue of the Auto Industry

by Steven Rattner · 19 Sep 2010 · 394pp · 124,743 words

The Key Man: The True Story of How the Global Elite Was Duped by a Capitalist Fairy Tale

by Simon Clark and Will Louch · 14 Jul 2021 · 403pp · 105,550 words

It's Not TV: The Spectacular Rise, Revolution, and Future of HBO

by Felix Gillette and John Koblin · 1 Nov 2022 · 575pp · 140,384 words

House of Huawei: The Secret History of China's Most Powerful Company

by Eva Dou · 14 Jan 2025 · 394pp · 110,159 words

The People's Platform: Taking Back Power and Culture in the Digital Age

by Astra Taylor · 4 Mar 2014 · 283pp · 85,824 words

The Virgin Way: Everything I Know About Leadership

by Richard Branson · 8 Sep 2014 · 315pp · 99,065 words

Human Frontiers: The Future of Big Ideas in an Age of Small Thinking

by Michael Bhaskar · 2 Nov 2021

Humans as a Service: The Promise and Perils of Work in the Gig Economy

by Jeremias Prassl · 7 May 2018 · 491pp · 77,650 words

Stigum's Money Market, 4E

by Marcia Stigum and Anthony Crescenzi · 9 Feb 2007 · 1,202pp · 424,886 words

The War on Normal People: The Truth About America's Disappearing Jobs and Why Universal Basic Income Is Our Future

by Andrew Yang · 2 Apr 2018 · 300pp · 76,638 words

The Establishment: And How They Get Away With It

by Owen Jones · 3 Sep 2014 · 388pp · 125,472 words

The fortune at the bottom of the pyramid

by C. K. Prahalad · 15 Jan 2005 · 423pp · 149,033 words

Ours to Hack and to Own: The Rise of Platform Cooperativism, a New Vision for the Future of Work and a Fairer Internet

by Trebor Scholz and Nathan Schneider · 14 Aug 2017 · 237pp · 67,154 words

Bold: How to Go Big, Create Wealth and Impact the World

by Peter H. Diamandis and Steven Kotler · 3 Feb 2015 · 368pp · 96,825 words

The Precariat: The New Dangerous Class

by Guy Standing · 27 Feb 2011 · 209pp · 89,619 words

Money and Government: The Past and Future of Economics

by Robert Skidelsky · 13 Nov 2018

The New Snobbery

by David Skelton · 28 Jun 2021 · 226pp · 58,341 words

Beyond Diversification: What Every Investor Needs to Know About Asset Allocation

by Sebastien Page · 4 Nov 2020 · 367pp · 97,136 words

The Divide: A Brief Guide to Global Inequality and Its Solutions

by Jason Hickel · 3 May 2017 · 332pp · 106,197 words

Markets, State, and People: Economics for Public Policy

by Diane Coyle · 14 Jan 2020 · 384pp · 108,414 words

Make Your Own Job: How the Entrepreneurial Work Ethic Exhausted America

by Erik Baker · 13 Jan 2025 · 362pp · 132,186 words

When More Is Not Better: Overcoming America's Obsession With Economic Efficiency

by Roger L. Martin · 28 Sep 2020 · 600pp · 72,502 words

The Age of Cryptocurrency: How Bitcoin and Digital Money Are Challenging the Global Economic Order

by Paul Vigna and Michael J. Casey · 27 Jan 2015 · 457pp · 128,838 words

Capitalism and Its Critics: A History: From the Industrial Revolution to AI

by John Cassidy · 12 May 2025 · 774pp · 238,244 words

Supremacy: AI, ChatGPT, and the Race That Will Change the World

by Parmy Olson · 284pp · 96,087 words

The Green New Deal: Why the Fossil Fuel Civilization Will Collapse by 2028, and the Bold Economic Plan to Save Life on Earth

by Jeremy Rifkin · 9 Sep 2019 · 327pp · 84,627 words

Trend Following: How Great Traders Make Millions in Up or Down Markets

by Michael W. Covel · 19 Mar 2007 · 467pp · 154,960 words

The Master Switch: The Rise and Fall of Information Empires

by Tim Wu · 2 Nov 2010 · 418pp · 128,965 words

What's Wrong With Economics: A Primer for the Perplexed

by Robert Skidelsky · 3 Mar 2020 · 290pp · 76,216 words

The Irrational Bundle

by Dan Ariely · 3 Apr 2013 · 898pp · 266,274 words

WEconomy: You Can Find Meaning, Make a Living, and Change the World

by Craig Kielburger, Holly Branson, Marc Kielburger, Sir Richard Branson and Sheryl Sandberg · 7 Mar 2018 · 335pp · 96,002 words

Fully Automated Luxury Communism

by Aaron Bastani · 10 Jun 2019 · 280pp · 74,559 words

Bad Money: Reckless Finance, Failed Politics, and the Global Crisis of American Capitalism

by Kevin Phillips · 31 Mar 2008 · 422pp · 113,830 words

The Black Box Society: The Secret Algorithms That Control Money and Information

by Frank Pasquale · 17 Nov 2014 · 320pp · 87,853 words

Don't Be Evil: How Big Tech Betrayed Its Founding Principles--And All of US

by Rana Foroohar · 5 Nov 2019 · 380pp · 109,724 words

Zero-Sum Future: American Power in an Age of Anxiety

by Gideon Rachman · 1 Feb 2011 · 391pp · 102,301 words

The Long Boom: A Vision for the Coming Age of Prosperity

by Peter Schwartz, Peter Leyden and Joel Hyatt · 18 Oct 2000 · 353pp · 355 words

The Corona Crash: How the Pandemic Will Change Capitalism

by Grace Blakeley · 14 Oct 2020 · 82pp · 24,150 words

When Free Markets Fail: Saving the Market When It Can't Save Itself (Wiley Corporate F&A)

by Scott McCleskey · 10 Mar 2011

The Oil and the Glory: The Pursuit of Empire and Fortune on the Caspian Sea

by Steve Levine · 23 Oct 2007 · 568pp · 162,366 words

Asset and Risk Management: Risk Oriented Finance

by Louis Esch, Robert Kieffer and Thierry Lopez · 28 Nov 2005 · 416pp · 39,022 words

The (Honest) Truth About Dishonesty: How We Lie to Everyone, Especially Ourselves

by Dan Ariely · 27 Jun 2012 · 258pp · 73,109 words

The Patterning Instinct: A Cultural History of Humanity's Search for Meaning

by Jeremy Lent · 22 May 2017 · 789pp · 207,744 words

Green Tyranny: Exposing the Totalitarian Roots of the Climate Industrial Complex

by Rupert Darwall · 2 Oct 2017 · 451pp · 115,720 words

Creating Unequal Futures?: Rethinking Poverty, Inequality and Disadvantage

by Ruth Fincher and Peter Saunders · 1 Jul 2001 · 267pp · 79,905 words

Global Financial Crisis

by Noah Berlatsky · 19 Feb 2010

That Used to Be Us

by Thomas L. Friedman and Michael Mandelbaum · 1 Sep 2011 · 441pp · 136,954 words

Platform Revolution: How Networked Markets Are Transforming the Economy--And How to Make Them Work for You

by Sangeet Paul Choudary, Marshall W. van Alstyne and Geoffrey G. Parker · 27 Mar 2016 · 421pp · 110,406 words

The Road to Somewhere: The Populist Revolt and the Future of Politics

by David Goodhart · 7 Jan 2017 · 382pp · 100,127 words

Good Economics for Hard Times: Better Answers to Our Biggest Problems

by Abhijit V. Banerjee and Esther Duflo · 12 Nov 2019 · 470pp · 148,730 words

Narrative Economics: How Stories Go Viral and Drive Major Economic Events

by Robert J. Shiller · 14 Oct 2019 · 611pp · 130,419 words

Pandemic, Inc.: Chasing the Capitalists and Thieves Who Got Rich While We Got Sick

by J. David McSwane · 11 Apr 2022 · 368pp · 102,379 words

Social Democratic America

by Lane Kenworthy · 3 Jan 2014 · 283pp · 73,093 words

Leadership by Algorithm: Who Leads and Who Follows in the AI Era?

by David de Cremer · 25 May 2020 · 241pp · 70,307 words

Team Human

by Douglas Rushkoff · 22 Jan 2019 · 196pp · 54,339 words

Radical Technologies: The Design of Everyday Life

by Adam Greenfield · 29 May 2017 · 410pp · 119,823 words

Young Money: Inside the Hidden World of Wall Street's Post-Crash Recruits

by Kevin Roose · 18 Feb 2014 · 269pp · 83,307 words

The Missing Billionaires: A Guide to Better Financial Decisions

by Victor Haghani and James White · 27 Aug 2023 · 314pp · 122,534 words

Super Founders: What Data Reveals About Billion-Dollar Startups

by Ali Tamaseb · 14 Sep 2021 · 251pp · 80,831 words

The Upswing: How America Came Together a Century Ago and How We Can Do It Again

by Robert D. Putnam · 12 Oct 2020 · 678pp · 160,676 words

Work Rules!: Insights From Inside Google That Will Transform How You Live and Lead

by Laszlo Bock · 31 Mar 2015 · 387pp · 119,409 words

The Filter Bubble: What the Internet Is Hiding From You

by Eli Pariser · 11 May 2011 · 274pp · 75,846 words

Liars and Outliers: How Security Holds Society Together

by Bruce Schneier · 14 Feb 2012 · 503pp · 131,064 words

There Is No Planet B: A Handbook for the Make or Break Years

by Mike Berners-Lee · 27 Feb 2019

The Participation Revolution: How to Ride the Waves of Change in a Terrifyingly Turbulent World

by Neil Gibb · 15 Feb 2018 · 217pp · 63,287 words

Social Life of Information

by John Seely Brown and Paul Duguid · 2 Feb 2000 · 791pp · 85,159 words

A Generation of Sociopaths: How the Baby Boomers Betrayed America

by Bruce Cannon Gibney · 7 Mar 2017 · 526pp · 160,601 words

Subscribed: Why the Subscription Model Will Be Your Company's Future - and What to Do About It

by Tien Tzuo and Gabe Weisert · 4 Jun 2018 · 244pp · 66,977 words

Fooled by Randomness: The Hidden Role of Chance in Life and in the Markets

by Nassim Nicholas Taleb · 1 Jan 2001 · 111pp · 1 words

Small Change: Why Business Won't Save the World

by Michael Edwards · 4 Jan 2010

The Powerful and the Damned: Private Diaries in Turbulent Times

by Lionel Barber · 5 Nov 2020

Chokepoints: American Power in the Age of Economic Warfare

by Edward Fishman · 25 Feb 2025 · 884pp · 221,861 words

eBoys

by Randall E. Stross · 30 Oct 2008 · 381pp · 112,674 words

The Open Organization: Igniting Passion and Performance

by Jim Whitehurst · 1 Jun 2015 · 247pp · 63,208 words

Trees on Mars: Our Obsession With the Future

by Hal Niedzviecki · 15 Mar 2015 · 343pp · 102,846 words

Digital Accounting: The Effects of the Internet and Erp on Accounting

by Ashutosh Deshmukh · 13 Dec 2005

Pity the Billionaire: The Unexpected Resurgence of the American Right

by Thomas Frank · 16 Aug 2011 · 261pp · 64,977 words

We Are All Fast-Food Workers Now: The Global Uprising Against Poverty Wages

by Annelise Orleck · 27 Feb 2018 · 382pp · 107,150 words

The Wisdom of Crowds

by James Surowiecki · 1 Jan 2004 · 326pp · 106,053 words

Open for Business Harnessing the Power of Platform Ecosystems

by Lauren Turner Claire, Laure Claire Reillier and Benoit Reillier · 14 Oct 2017 · 240pp · 78,436 words

You've Been Played: How Corporations, Governments, and Schools Use Games to Control Us All

by Adrian Hon · 14 Sep 2022 · 371pp · 107,141 words

Pandora's Box: How Guts, Guile, and Greed Upended TV

by Peter Biskind · 6 Nov 2023 · 543pp · 143,084 words

Think Like an Engineer: Use Systematic Thinking to Solve Everyday Challenges & Unlock the Inherent Values in Them

by Mushtak Al-Atabi · 26 Aug 2014 · 204pp · 66,619 words

Rocket Billionaires: Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, and the New Space Race

by Tim Fernholz · 20 Mar 2018 · 328pp · 96,141 words

Gigged: The End of the Job and the Future of Work

by Sarah Kessler · 11 Jun 2018 · 246pp · 68,392 words

Brotopia: Breaking Up the Boys' Club of Silicon Valley

by Emily Chang · 6 Feb 2018 · 334pp · 104,382 words