Iron Curtain: The Crushing of Eastern Europe, 1945-1956

by

Anne Applebaum

Published 30 Oct 2012

Stakhanov’s achievement was brought to Stalin’s attention, and subsequently turned into a miniature cult of personality. There were articles, books, and posters about Stakhanov as well as Stakhanov streets and Stakhanov squares. A Ukrainian town was renamed Stakhanov in his honor. Heroes of Labor were renamed Stakhanovites after him too, and Stakhanovite competitions were held all over the Soviet Union. The Eastern European communists would have known the Stakhanov cult very well, and some of them imitated this model with great precision. Eastern Germany’s Stakhanov was Adolf Hennecke, a coal miner who astonished his comrades in 1948 and dug 287 percent of his production quota.

…

They were celebrated in the newspapers and on the radio, and they featured in public events, newsreels, and parades. Sometimes they received unexpected perks, as one female Polish textile worker remembered: In 1950 or 1952 … I don’t remember exactly … I was chosen as the best Stakhanovite in my factory. I did 250 percent of the quota … One day I went to work, of course in my daily clothes, because you do not go to work in Sunday clothes. And they gave me a ticket saying that I am going to the Stakhanovite ball. I said I was not going because I was not dressed up, but they ordered me to go. So I went with the others. It was an amazing experience: me, an ordinary worker of a sewing department, visited President Bierut himself.

…

For one, it created perverse incentives: workers competed to finish quickly and ignored quality. As a result, “socialist competitions” never made the economy more productive, in the Soviet Union or anywhere else. The economic historian Paul Gregory reckons that in the USSR the Stakhanovite movement had no impact on labor productivity whatsoever: the cost of the expensive prizes and higher wages for the Stakhanovites canceled out whatever value industry might have gained from the superhuman effort of individual workers.62 In political terms, the movement’s impact was more mixed. In some places, the daily quotas became a bone of contention, particularly as they began to rise faster than wages and living standards, and the party had to invent new techniques to stop the complaining.

The Story of Work: A New History of Humankind

by

Jan Lucassen

Published 26 Jul 2021

And this was exactly what happened, nationwide after Pravda – instigated by the People’s Commissar for Heavy Industry Ordzhonikidze – started to report about this record and, within a fortnight, coined the term ‘Stakhanovite movement’, and ‘recordmania’ swept the country, peaking in November 1935. Stakhanovite brigades sprang up, assembled among workers who had already distinguished themselves, and closely resembled the shock brigades of the late 1920s, followed by the All-Union Conference of Stakhanovites and Stakhanovite schools (on-the-job training courses by leading Stakhanovites). This movement appealed especially to young males, whereas women were less likely to become Stakhanovites than men: Let’s say that I have a mother and a wife. My mother is old and cannot work in the kolkhoz, but she can work around the house and take care of the children.

…

My mother is old and cannot work in the kolkhoz, but she can work around the house and take care of the children. Now, in this case, I and my wife can both work quite easily, put in all the work-days we are supposed to, and thereby become Stakhanovites. But you on the other hand are married, your wife had several children and there is no grandmother in the house to take care of them. Then, your wife cannot work very much . . . But my wife, who has an older woman in the house, can be a Stakhanovite and get a little suckling pig.148 But those who did, like Pasha Angelina, the first female tractor brigade leader, attained rock star status. Her commitment, not only to shock work, is illustrated by the following chastúshka (a humorous folk song with high beat frequency) that she recited: Oh, thank you dear Lenin.

…

The man depicted here is the steelworker Lukashov, who worked himself up to the position of engineer in the ‘Hammer and Sickle’ factory in Moscow, 1932. ‘Civilized life – productive work’ was a message for the members of Komsomol, the communist youth organization, who had to set an example through their actions. 16. ‘A glorious production model’ worker proudly shows her Stakhanovite-like diploma and medal to her excited daughter and two sons; in the background is the factory where she works, China, 1954. 17. Assembly line workers pose for a promotional film at the Ford factory in Highland Park, Michigan, to mark the 10 millionth Model T in 1924. The first Model was made less than sixteen years previously. 18.

To the Edge of the World: The Story of the Trans-Siberian Express, the World's Greatest Railroad

by

Christian Wolmar

Published 4 Aug 2014

Not surprisingly, as a result, the accident rate rose; and even minor mishaps could easily result in the hapless local manager being accused of being a ‘wrecker’ bent on destroying socialist society, the worst possible accusation. Under Kaganovich, too, Stakhanovite efforts were encouraged to improve productivity. Named after a miner who supposedly carved out more than 100 tons of coal in a single shift, which was, in fact, an obvious charade, Stakhanovite efforts were imposed on the railways, but to terrible effect. Specially selected train drivers were set up to ensure their locomotives pulled greater loads, or used less coal per verst, but as Westwood suggests, this usually meant that all the engineer did was ‘drive his engine badly, “thrashing” it so it produced a third more steam per hour’; but while this did increase the speed, it simply meant it ‘raised fuel consumption per horsepower to a much higher rate and brought his fireman [who had to shovel the coal into the fire box] to a state of collapse’.20 Even the relatively neglected passenger services improved in the 1930s, thanks to the investment on the line.

…

Transport delays – particularly on the Trans-Siberian, which was now expected to carry a much heavier load than previously – were an all too visible reflection of the society’s inefficiency, and as J. N. Westwood, the Russian railway historian, suggests, ‘Government and Party remained unconvinced that the railways were working anywhere near their real limit, a conflict that was almost inevitable . . . the two weapons [in government hands] were the purge and the Stakhanovite movement.’18 Kaganovich had more blood on his hands than almost any other of his contemporary Communist leaders, having organized forced grain confiscations during the starvation deliberately brought on by the regime in the early 1930s in Ukraine as a punishment. He was one of those who took the hardest line against the slightly better-off peasants characterized as kulaks (rich peasants, but often misused as a way of identifying those reluctant to hand over grain) by the regime, a group that was almost exterminated under Stalin’s forced collectivization of agriculture.

…

I., 179–80, 205, 211 Li Hongzhang, 70–2, 123–4, 127 Liandong peninsula, 122–3, 126, 130–1 Liaotung peninsula, 109 Lissanevich, Matilda Ivanovna, 50–1 Listvyanka, 89–90 Liverpool & Manchester Railway, 13–14 Livitsky, Colonel, 184 loading gauge, 257 locomotives fuelling of, 173 numbers of, 118 Russian-manufactured, 12, 20–1 withdrawal of steam, 251 Zaamurets, 179 Lodian, L., 76, 78, 119 London Underground, 92 Maby, Deborah, 256 Magnitnaya Mountain, 217 Magnitogorsk, 217 Main Company of Russian Railways, 25 Main Line (Pennsylvania), 45 Manchouli, 122, 182 Manchukuo, 215, 224 Manchuria, 31, 37 and construction of BAM, 231, 259 local hostility to Russians, 124–5 railway construction, 68–72, 121–30 Russian atrocities, 128–9 and Russian foreign policy, 165–9 and Russo-Japanese War, 131–42 struggle for control, 213–15, 223–4, 229–30 Manley, Deborah, 254 Maria Feodorovna, Empress, 150 Mariinsk, 198 Marks, Steven, 5, 34, 37, 59, 67, 96, 120, 145, 171 Martinsk, 105 Meakin, Annette, 107–8, 116, 252 Menocal, Daniel de, 166 Mezheninov, Nicholas, 78, 83–5 Middlesex Regiment, 186–7 Mid-Siberian line, 65–6, 74, 103, 105 construction, 78–9, 83–6 costs, 86, 88 Mikhailovsky, Eugenia, 81 Mikhailovsky, Konstantin Yakovlevich, 73–4, 81–4, 86 mines, 10, 172, 207 missile systems, rail-based, 254–5 missionaries, 123 Mitchell, Elsie, 208, 211 Mogot, 240 Mongolia, 7, 182, 223–3, 230 Montefiore, Simon Sebag, 224 Morison, Mr, 31 Morning Star, 253 Morse, Samuel, 33 Moscow meat deliveries to, 158 panorama, 110 Stalin’s escape route from, 226 Moscow–Chelyabinsk line, 64 Moscow Metro, 221 Moscow time, 115, 258 mosquitoes, 76, 87 Mukden, 128, 138–9, 214 Murarev, Count Mikhail, 123 Murayev, Nicholas, 30–3, 36, 69 Murmansk, 174 Murphy, Dervla, 242–3, 245 Mysovsk, 88, 101 Nagelmackers, Georges, 109, 114, 117, 163 Nakhodka, 255 Nansen, Fridtjof, 170 Napoleon Bonaparte, 194 Nauen, 194 New York Air Brake Co., 94 Newby, Eric, xix, 30, 253–4 Nicholas I, Tsar, 2–3, 5, 11 and railways, 13–21, 24 Nicholas II, Tsar, 58, 70, 249 foreign tour, 59–60 and railways, 59–62 and Russo-Japanese War, 139–41 Nikolaevsk, 113, 200–1 Nikolayev Railway, 16–24, 74 fares, 22 finance, 21 gauge, 18–19 lack of connections, 23 route, 18, 20 speed of construction, 21 topography, 20 travelling conditions, 22 volume of traffic, 21 Nizhneudinsk, 198 Nizhny-Novgorod, 29, 31, 39 Nizhny Tagil, 12 North Korea, 245 Novokuznetsk, 217, 219, 222 Novonikolayevsk, 73, 84–6, 156, 198, 218 see also Novosibirsk Novosibirsk, 219, 260 station architecture, 220 see also Novonikolayevsk Novosibirsk Railway Museum, 108 Ob, river, 42, 68, 73, 82, 84–5, 101, 220 Ob River–Krasnoyarsk line, 65 October Manifesto, 139–40 Odessa, 24–5, 80, 86, 184–5 Odessa Railway, 49–50 Odessa University, 48 oil, 159, 174, 246 and environmental damage, 243–4 Old Believers, 144–5 Omsk, 73–4, 81–2, 161, 260 and civil war, 184, 187–8, 190, 195–8 coal thefts, 119–20 garden city, 156 panorama, 110 population increase, 155 station architecture, 92, 253 Omsk paper currency, 197 Omsk–River Ob line, 65 Orenburg, 42, 190 Orient Express, 109 Orthodox Church, 144–5 Orwell, George, 236 Ozerlag camp complex, 234 Pacific Fleet, Russian, 38, 56, 167 Page, Martin, 93–4 Panama Canal, 75 panoramas, 109–10 Paris, 25, 51 Paris Exposition Universelle, 84, 109–10, 114 passports, internal, 1, 21, 147–9 Pasternak, Boris, 193 Pauker, General German Egorovich, 44 Pavlovsk, 15 Peking–Paris road race, 162–3 Penrose, Richard, 152–3 Penza, 140, 180 Perm, 29, 39, 41–2, 192, 195, 209 permafrost, 65, 69, 103, 125, 168 and construction of BAM, 232–3, 239–40, 243, 247 Pertsov, Alexander, 134–5 Peter the Great, Emperor, 9, 20 Peyton, Mr, 32 photography, 253–4 Plehve, Vyacheslav von, 141 Pogranichny, 122 Pokrovskaya, Vera, 81 Polish provinces, 14, 24, 28, 144 Poltava, 151 Polyanski (agent), 51 Port Arthur, 109, 114, 123, 126, 129, 131, 133–4, 137, 139, 165 Port Baikal, 89, 101, 135 post houses, 4–5 Postyshevo, 233 Posyet, Konstantin, 39–40, 44, 52 Primorye region, 36–7, 40–1 prisoners of war, 226, 234, 246 Progressive Tours, 253 propaganda, 203–7, 252 Pushechnikov, Alexander, 88–9, 96, 122 Putin, Vladimir, 244 Pyasetsky, Pawel, 109–10 rails, convex, 12 railway administrators, enlightened, 151–2 ‘railway barons’, 26, 42, 50 railway colonies, 93 railway currency, 213 Railway Guard, 127–8, 130 railway managers, and Stalin’s purges, 221–3, 225 railway troops, 238 railway workers, 117–20, 156–7 wages, 118–19 railways, horse-drawn, 11–13, 30 railways, military, 24, 45 Ransome, Arthur, 206–7 Ready, Oliver, 114 Reid, Arnot, 102–3 roads, 2–3, 5–6, 13, 20, 98, 162, 257 Rosanov, Sergei, 186 Rothschilds, 46 rouble, linked to gold, 57 Royal Engineers, 95 Russia absolutism, 1 advent of railways, 27–8 censorship, 111 collapse of communism, 247–8, 257, 259 economy, 1–3, 26, 28, 55–6, 58, 95, 97–8, 255 expansion of railway network, 41–2 expansionist policies, 122–4, 130, 139 first horse-drawn railway, 11–12 German invasion, 224–5, 232, 258 industrialization, 55, 57, 95, 207, 211, 216–19, 221, 256, 258 land reforms, 154 liberalization, 21–2, 154 opposition to railways, 13–14, 16 unified railway network, 53 Russian civil war, xvi, 133, 138, 171–201, 223 Russian Revolution (1905), xvi, 154 (1917), xvi, 9, 121, 172, 174–8, 214 Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, 199–201 Russian Technical Society, 67 Russo-Japanese War, xvi, 91, 94, 107, 121, 129–42, 154, 161, 163, 165 peace treaties and aftermath, 139, 166–7, 213–14 Russo-Turkish War, 19, 36–7, 40, 49, 140–1 St John’s, Newfoundland, 64 Saint Nicholas, 73 St Petersburg assassination of von Plehve, 141 construction of, 20 massacre of demonstrators, 139 meat deliveries to, 158 renamed Petrograd, 162 St Petersburg–Moscow highway, 2 St Petersburg–Moscow Railway, see Nikolayev Railway St Petersburg time, 115 St Petersburg–Warsaw Railway, 24–5, 28 saints’ days, 104 Sakhalin Island, 31, 80, 199, 201, 242, 249 Samara, 140 see also Kuibyshev Samarkand, 39 San Francisco, 32 Schaffhausen-Schönberg och Schaufuss, Nikolai, 168 schools, building of, 157–8 Sea of Japan, 2, 7, 31, 173 Second World War, 19, 133, 200, 218–19, 221, 223–7, 229–30, 233 Semipalatinsk, 218 Semipalatinsk Cossacks, 185 Semyonov, Gregori, 182–5, 192, 198, 200 serfs, 12, 16–18, 34, 74, 141, 178 emancipation of, 11, 34, 145, 147 Sevastopol, siege of, 24, 37 Severobaikalsk, 231, 235, 241 Severomuysky Tunnel, 241, 244, 246 Shanghai, 114, 164 Shika, river, 69, 88, 101 Shoemaker, Michael Myers, 115 shovels, 81 Siberia Allied intervention, 172–201 architecture, 156–7 area, 7–8 cartography, 66–7 climate, 1, 7–8, 243, 246 economy, 31, 36, 207 fire damage, 243 first railway, 42–3 immigration, 143–60, 207, 220 increased productivity, 158–9 indigenous peoples, 11, 65, 118, 145–6, 149 industrialization, 207, 211, 216–19, 220–2, 256, 258 infrastructure improvements, 59, 61, 83, 98, 159 population, 1, 7, 10–11, 143, 159, 219 regionalist movement, 35 and Russian Empire, 34–6 time zones, 7 travel, 3–7, 32 urbanization, 154–6 Siberian Committee, 33–4 signallers, 118–19 Simpson, James, 150–1 Sino-Japanese War, 70–1 slaves, American, 35 sleepers, 64, 81, 84, 103, 106, 239 Sleigh, Mr, 31 sleighs, 3, 6, 32 Slyudyanka, 228 snowdrifts, 104 Sofiysk, 31 Solzhenitsyn, Alexander, 231 Some Like It Hot, 116 South Manchuria Railway, 126, 128–9, 137–9, 164, 214 Southwestern Railway, 50 Sovetskaya Gavan, 231, 233, 248 Soviet Sociology, 237 Soviets, 179 Sretensk, 38, 41, 88–9, 101, 108, 121–2, 168 Stakhanovite movement, 222–3 Stalin, Joseph, 10, 177, 215, 224–6, 229–30, 235 his death, 226, 234, 242 escape route from Moscow, 226 industrialization under, 207, 211, 216–19, 220–2, 256, 258 his train, 212, 252 Standard newspaper, 133 Stankevich, Andrei, 152 stations, 27, 74, 91–3, 156–7, 219–20, 257 architecture, 92, 157, 220 catering, 103, 107–8, 209–10 military areas, 157 steamboats, 4, 13 Stephenson, George and Robert, 12 Stevens, John F., 191 Stolypin, Pyotr, 154 submarine warfare, 176 submarines, 173 Suchan coal mines, 187 Sudan, 64 Suez Canal, 37, 70, 86, 164 suicides, 10 Suprenenko, Governor, 30 Sverdlovsk, 219 see also Yekaterinburg Swedish Red Cross, 185 Syzran, 42 taiga, 68, 78–9, 83–4, 236, 238, 243 tarantasses, 3–4, 6, 32, 91, 106 Tashkent, 218 Tayga, 155 Taylor, Richard, 204, 207 Tayshet, 231, 233–4, 239, 246 Tblisi, 48 telegas, 3 telegraph systems, 33, 140, 179, 194 Tibet, 233 tigers, 80 timber, shortages of, 64, 73, 84, 124, 126 Times, The, 22, 165 Timireva, Anna, 197 Tokyo, 161, 188 Tomsk, 38, 41, 68, 86, 107, 155–6, 217 First World War bottleneck, 172, 175 and railway administration, 68, 120 Tomsk province, 155 track gauge, 15–16, 18–19, 137–8, 256–7 trains armoured trains, xvi, 179, 183, 193, 203 butter trains, 158 coal trains, 172 Lux Blue Express, 212 luxury trains, 108–11, 114, 163–4, 252 propaganda trains, 203–7 Rossiya, 117, 257–8 troop trains, 133–4 tsar’s train, 44, 113, 198 ‘typhus trains’, 197–8 V.

The Meritocracy Trap: How America's Foundational Myth Feeds Inequality, Dismantles the Middle Class, and Devours the Elite

by

Daniel Markovits

Published 14 Sep 2019

The baton of industrious effort has been largely detached from the increasingly redundant middle class and passed up the income ladder. This merger of industry and honor explains why the middle class experiences its enforced idleness as insulting and even degrading and why the working rich commit to epidemic industry that the pursuit of mere wealth cannot rationalize. Today’s Stakhanovites are the one-percenters. POVERTY AND WEALTH Every economy may be described in terms of two kinds of inequality: high-end, which concerns the gap between the rich and the middle class; and low-end, which concerns the gap between the middle class and the poor. Economic inequality can therefore grow and shrink at the same time, as rising high-end and falling low-end inequality occur together.

…

One might even say, speaking loosely, that management has itself become financialized. Like the innovations that transformed finance, the cascading innovations behind the managerial revolution did not arise spontaneously. Instead, they were all—every one—generated from within meritocracy, by and for the newly available supply of super-skilled, Stakhanovite workers coming out of America’s newly meritocratic schools and universities. The financial instruments through which corporate raiders accomplish their takeovers, like the other financial innovations just described, required super-skilled finance workers in order to construct, price, and trade them.

…

Most important, a corporate raider cannot improve a target firm’s economic performance or increase its stock price unless he can replace incumbent managers with expert and industrious substitutes. The entire conceit of shareholder activism depends on deploying the increased elite managerial capacity that gives corporate takeovers their economic foundation. It requires a ready supply of Stakhanovite, super-skilled top managers who are willing and able effectively to exercise the vast powers of command that running a firm directly (without relying on middle managers) requires. It is therefore again no happenstance that the 1980s takeover boom coincided with rapid expansions and repositionings in the institutions that produce managerial capacity.

Why America Must Not Follow Europe

by

Daniel Hannan

Published 1 Mar 2011

To which it is tempting to remark, as Sarah Palin might put it, How’s that working out for y’all? Then again, no one ever really believed that the Lisbon Agenda would have much impact in the real world. It was intended in the spirit of one of those Soviet slogans about higher production: a Stakhanovite statement of intent. The French philosopher René Descartes famously imagined that everything we thought we could see was in fact being manipulated by a malicious demon who controlled our senses. Eurocrats evidently see themselves in the role of that demon. The EU they describe is one of high growth, full democracy, and growing global influence.

Cows, Pigs, Wars, and Witches: The Riddles of Culture

by

Marvin Harris

Published 1 Dec 1974

Since there are several big men per village and community, these plans and preparations often lead to complex competitive maneuvering for the allegiance of relatives and neighbors. The big men work harder, worry more, and consume less than anybody else. Prestige is their only reward. The big man can be described as a worker-entrepreneur—the Russians call them “Stakhanovites”—who renders important services to society by raising the level of production. As a result of the big man’s craving for status, more people work harder and produce more food and other valuables. Under conditions where everyone has equal access to the means of subsistence, competitive feasting serves the practical function of preventing the labor force from falling back to levels of productivity that offer no margin of safety in crises such as war and crop failures.

…

This discovery effectively destroys one of the shoddiest myths of industrial society—namely that we have more leisure today than ever before. Primitive hunters and gatherers work less than we do—without benefit of a single labor union—because their ecosystems cannot tolerate weeks and months of intensive extra effort. Among the Bushmen, Stakhanovite personalities who would run about getting friends and relatives to work harder by promising them a big feast would constitute a definite menace to society. If he got his followers to work like the Kaoka for a month, an aspiring Bushman big man would kill or scare off every game animal for miles around and starve his people to death before the end of the year.

Empire of Things: How We Became a World of Consumers, From the Fifteenth Century to the Twenty-First

by

Frank Trentmann

Published 1 Dec 2015

Across Europe, conservatives, home-builders and Christian reformers were singing variations on the same tune of civic consumerism: a man who owned his home had a stake in his country, making him an upright, loyal citizen, a buttress of family life and freedom against collectivism. In fact, not even Stalin’s Soviet Union was altogether immune from the siren call. Late Stalinism dangled the ideal of domestic comfort and home ownership before its new elite, the over-achieving Stakhanovites. In a typical piece of middle-brow fiction from 1950 Russia, Dimitri returns home and muses about his new status in life: ‘Homeowner! How the sense of this world has changed! Homeowners in Rudnogorsk were now the best shock-workers and engineers, working people. Dimitri was impatient to go with Marina to look at their new home, but it was late.

…

‘Life is getting better, life has become more joyous,’ Stalin pronounced in 1935. This slogan was trumpeted from department stores, the fun fair at Gorky Park and in popular song. After years of deprivation, comrades were told to enjoy tennis, silk stockings and jazz by Antonin Ziegler’s Czech band. Red Army officials learnt to dance the tango. Heroic workers, the Stakhanovites, received gramophones and a Boston suit (for him) and a crêpe de Chine dress (for her). A Soviet House of Fashions opened its doors in Moscow in 1936, and the USSR set out to overtake France in the production of perfume. Novelty was encouraged. Chocolate and sausage makers raced to expand their ranges; in 1937, Moscow’s Red October factory produced over five hundred different kinds of chocolates and candies.

…

This approach can be understood as a particular Soviet version of the ‘politics of productivity’ which all inter-war regimes wrestled with. Dangling watches and phonographs in front of workers would make them work harder. ‘We want to lead a cultured life,’ Party leader Miron Djukanov, a miner, told fellow Stakhanovites in 1935: ‘[W]e want bicycles, pianos, phonographs, records, radio sets, and many other articles of culture.’59 Greater productivity, in turn, would allow socialism to overtake and crush capitalism. Stalinism aimed at an extreme version of the ‘industrious revolution’. Hard work would catapult ordinary people into a new material era, as in the case of E.

Reset: How to Restart Your Life and Get F.U. Money: The Unconventional Early Retirement Plan for Midlife Careerists Who Want to Be Happy

by

David Sawyer

Published 17 Aug 2018

Action If you do believe there’s more to life than this – that you are the captain of your fate – then a financial independence plan with stock market investing at its core is what RESET suggests. All you need do is devise a plan and stick to it. Mutual funds: actively managed So, without further ado, let’s move on to the Stakhanovite workhorse and secret weapon of the RESET investing plan: the humble mutual fund. There are two types of mutual funds: actively managed and passively managed. Let’s take actively managed first. When most people refer to “mutual funds” or “unit trusts” or “OEICs”, they are talking about ones that are actively managed.

…

Fidelity now offers this service to UK small investors (us) without having to go through an adviser. Do your stocks research. Favour stocks that pay dividends, but consider those that don’t, too. Adopt a long-term (five-year-plus) stock investment strategy, as Warren Buffett does. Don’t try to time the market; set and forget. Let that globally diversified low-cost Stakhanovite bunch of index funds do 95%-plus of your portfolio’s heavy lifting. Keep an eye on the charges. For example, towards the middle of last year, we invested well under 5% of our stash in three companies: Apple (quarter), Microsoft (quarter) and Berkshire Hathaway B (half) after cashing in Standard Life windfall shares.

Rush Hour: How 500 Million Commuters Survive the Daily Journey to Work

by

Iain Gately

Published 6 Nov 2014

Although, in theory, every comrade over the age of eighteen was entitled to order a new car, a Volga cost six times the average worker’s annual salary, and there was a waiting list of eight to ten years. Indeed, the only types of people likely to be able to drive to work in Russia in the 1950s and 1960s were members of the elite – artists with international reputations, Olympic champions, military and party officials and Stakhanovites*4 who could jump the queues and get a car straight away. Second-hand cars were equally hard to come by for the average worker. Once people had a Volga, they were reluctant to sell them and they also had to go through official centres to do so, where ‘a commission of specialists evaluated the car and set a price’.

…

They decided that as ‘a fundamental norm’ the desirable time for trips to work should not exceed 30–40 minutes for medium-sized cities, or an hour for larger ones. Beyond these limits productivity seemed to fall by 2.5 to 3 per cent for each extra ten minutes spent in transit. Official disapproval and the general absence of facilities notwithstanding, commuting crept into the Soviet Union in the last decade of its ‘great stagnation’ (1964–85). The Stakhanovites of freedom of movement appeared in the main in small cities. They were categorized as ‘young, low-skilled workers, occupying positions requiring low qualifications and yielding low wages’, and served as cannon fodder during the USSR’s last, futile attempt to win the Cold War through communist economics.

Re-Educated: Why It’s Never Too Late to Change Your Life

by

Lucy Kellaway

Published 30 Jun 2021

The result: Daniel was still lazy and his work did not improve noticeably, but I think he liked business studies – and me – more than before. I don’t teach him anymore but he shouts, ‘Hello, Miss Kellaway!’ whenever he sees me in the playground. To do my job better I need to understand the answer to a more fundamental question than sticks or carrots: why does one child work and the other doesn’t? Why is Jade a Stakhanovite and Zian a lotus-eater? There are a few universal truths: girls work harder than boys, I suspect mainly because they are less complacent. There is also a work ethic built into the fabric of some families, particularly some of the immigrant ones, that strikes me as both wonderful and entirely alien.

One Minute to Midnight: Kennedy, Khrushchev and Castro on the Brink of Nuclear War

by

Michael Dobbs

Published 3 Sep 2008

"Only someone with no military background, and no understanding of the paraphernalia that accompanied the rockets themselves, could have reached such a conclusion." The most Soviet commanders on Cuba could do was order a crash program to bring all the missiles to combat readiness as quickly as possible. Soviet soldiers were accustomed to Stakhanovite labor campaigns, organized bursts of mass enthusiasm designed to "fulfill and overfulfill the plan." Fortunately, the R-12 regiments were almost at full strength. By October 23, 42,822 Soviet soldiers had arrived in Cuba—out of a planned deployment of around 45,000. Overnight, the missile sites swarmed with laborers.

…

Shumkov, Nikolai Siberia Sidorov, Ivan Sierra del Cristal Mountains Sierra del Rosario Sierra Madre Sierra Maestra Mountains Sigint (signals intelligence) Silver Bank Passage Single Integrated Operational Plan (SIOP) Siskiyou County Airport 613th Tactical Fighter Squadron Skagerrak Strait Sochi Sokolov, Aleksandr Solovyev, Yuri Sopkas Sorensen, Theodore Khrushchev letter drafts merged by Sound Surveillance System (SOSUS) Southeast Asia South Pacific, nuclear tests in Soviet soldiers, Cuban views on Soviet Union Berlin and China's schism with CIA revelation of Cuban missile sites of in Cuba Cuba's defense agreement with demise of economy of Hungary's relations with intelligence problems of nuclear equality pursued in nuclear tests of RFK's visit to "Task 1 targets" in U-2s over U.S. north vs. south defense against weakness of in World War II Spain Spanish-American War Special Group (Augmented) spetsnaz alerts Sputnik Stakhanovite labor campaigns Stalin, Joseph World War II and Standard Oil of New Jersey State Department, U.S. decoys from Dobrynin summoned to "further action" and Khrushchev correspondence and planning of Cuban government in U-2 loss and Statsenko, Igor Stern, Sheldon Steuart Motor Company building Stevenson, Adlai Strategic Air Command (SAC) B-52s and DEFCON-2 of DEFCON-3 of LeMay's creation of Minuteman missiles and in search for Grozny U-2 loss over Soviet Union and Strategic Rocket Forces strategic weapons, Soviet disadvantage in submarines, Soviet Foxtrot, see Foxtrot submarines naval blockade and U.S.

Mr Five Per Cent: The Many Lives of Calouste Gulbenkian, the World's Richest Man

by

Jonathan Conlin

Published 3 Jan 2019

As of 1928 he had a wife to support, the actress Doré Plowden, whom he had met at the tables in Monte Carlo. Nubar was also concerned at the growing influence of his brother-in-law, Kevork. Kevork’s character was very different from Nubar’s: quiet, reserved and somewhat nervy.41 In the early years Calouste had treated Kevork (‘Kev’) as something of a drudge, taking full advantage of his Stakhanovite love of accounts. Calouste may have hoped that Kev’s good habits would rub off on his daughter, Rita. The pair had had a son, Mikhael, in 1927. Married twice, Nubar remained childless, and was doomed to remain so, having suffered a childhood attack of mumps, which had left him infertile. Could Calouste really have forgotten this?

…

Like other members of the pre-1914, London-based ‘aristocratic bourgeoisie’ described by historians Jose Harris and Pat Thane, so Gulbenkian ‘combined grand dynastic aspiration with an unpretentious devotion to the ethic of work’.12 Gulbenkian preached this work ethic to his son and grandson, and practised it to an almost Stakhanovite degree himself. Though his itinerant lifestyle orbited around grand hotels and resorts synonymous with opulence, his was not a life of ease. His dress was formal, yet modest: in middle age he sometimes evaded paparazzi simply by dint of not looking like a millionaire. Irritated to discover that his expensive Patek Philippe had broken yet again, Gulbenkian asked his valet where he had purchased his own more reliable watch.

Working the Phones: Control and Resistance in Call Centres

by

Jamie Woodcock

Published 20 Nov 2016

A day and a half on the job . . . and then fired for being incapable!’3 In the call centre, the television screen on the wall taunted workers with sales figures, acting as a constant reminder of how each individual worker compares to others. I found it nerve-wracking as I struggled to get sales while watching the more established, near-Stakhanovite workers constantly adding more sales. However, after a month or so I began to regularly make sales, not quite enough to ‘graduate’, but enough not to suffer Linhart’s fearful outcome. In a typical shift I would make approximately three to four hundred phone calls. The majority of these calls would go through to answerphone, especially during the part of the shift taking place during normal working hours.

The Meaning of Everything: The Story of the Oxford English Dictionary

by

Simon Winchester

Published 1 Jan 2003

And he eventually realized it when, some years later, he was able to write approvingly of the speed with which his own dictionary-making machine was functioning. `We have already overtaken Grimm, and have left it behind.' But that was in the future: just now, matters seemed to grind exceeding slow. These first 8,365 words had been won with the expenditure of Stakhanovite degrees of labour. * * * Before describing just what was in—and what was not in— Murray's first fascicle, a small but significant fact needs to be pointed out: something that will make rather more sense when we come to the very end, or least to the most modern part, of this story. A detailed textual analysis throws up in these very early parts of the Dictionary certain slight idiosyncrasies of style, a certain lack of consistency, a vague impression of (dare one say it?)

Independent Diplomat: Dispatches From an Unaccountable Elite

by

Carne Ross

Published 25 Apr 2007

If you make an enormous effort of imagination, you can just about conjure up a picture of the human beings whose existence is at stake — the victims of genocide in Rwanda, the civilians massacred during a rebel advance in the Congo — but it is a stretch, and sooner or later you stop doing it because it’s upsetting, tiring and, frankly, unnecessary. It’s easier just to do what’s necessary, write the report, negotiate the resolution, get home (our hours are long, even by the Stakhanovite standards of New York City). And slowly but surely you become deadened to it all. Wars, brutalities, peace plans, blah, blah, blah. Though we were at the heart of things, we seemed to be missing the point. Terms — diplomatic words, statistics, resolutions — were our tools to arbitrate a world of blood and agony.

Emergence

by

Steven Johnson

It would be like an ant colony where each ant started the day with a carefully planned agenda: forage from six to ten; midden duty until noon; lunch; and then cleanup in the afternoon. That’s a command economy, not a bottom-up system. So does this mean our genes are secret Stalins, doling out the fixed plan for growth to the Stakhanovites of our cells? Are we more like a socialist housing complex than an ant colony? No one questions that DNA exerts an extraordinary influence over the development of our cells, and that each cell in our body contains the same genetic blueprint. If each cell were simply reading from the chromosomal playbook and behaving accordingly, you could indeed make the argument that our bodies don’t function like ant colonies.

Inventing the Future: Postcapitalism and a World Without Work

by

Nick Srnicek

and

Alex Williams

Published 1 Oct 2015

; Leon Trotsky, The Transitional Program: Death Agony of Capitalism and the Tasks of the Fourth International (London: Bolshevik Publications, 1999). 6.On the criteria of desirability, viability and achievability, see Erik Olin Wright, Envisioning Real Utopias (London: Verso, 2010), pp. 20–5. 7.For an example of the former, see the Stakhanovite movement, or Lenin’s comments on Taylorist management methods: ‘The Russian is a bad worker compared with people in advanced countries … We must organise in Russia the study and teaching of the Taylor system and systematically try it out and adapt it to our own ends.’ Vladimir Lenin, ‘The Immediate Tasks of the Soviet Government’, 1918, Marxists Internet Archive, at marxists.org; Lewis H.

The Ghost

by

Robert Harris

Published 22 Oct 2007

“And nobody saw this coming?” “I raised it with Adam every so often. But history doesn’t really interest him—it never has, not even his own. He was much more concerned with getting his foundation established.” I sat back in my seat. I could see how easily it all must have happened: McAra, the party hack turned Stakhanovite of the archive, blindly riveting together his vast and useless sheets of facts; Lang, always a man for the bigger picture—“the future not the past”: wasn’t that one of his slogans—being feted around the American lecture circuit, preferring to live, not relive, his life; and then the horrible realization that the great memoir project was in trouble, followed, I assumed, by recriminations, the sundering of old friendships, and suicidal anxiety.

Global Inequality: A New Approach for the Age of Globalization

by

Branko Milanovic

Published 10 Apr 2016

For a long time, socialist policy-makers held that too much wage equalization eliminated incentives for acquiring new skills and working hard. In the “heroic” phase of socialism, this could be compensated for through “socialist emulation”—psychic income and social esteem acquired by those who, like the miner Aleksei Stakhanov, eponymous hero of the Stakhanovite movement, worked hard for no pecuniary return. But, in the long run, this system was unsustainable. A slew of socialist reforms in the 1960s were supposed to address defects in the system; allowing enterprises to keep more money and distribute it to the best workers was supposed to increase productivity.

The Descent of Woman

by

Elaine Morgan

Published 1 Feb 2001

He speculates that ‘man’s earliest means of communicating ideas was by gestures with the hands’, and perhaps ‘an increasing preoccupation of the hands with the making and using of tools could have led to the change from manual to oral gesturing as a means of communication’. This is ingenious. But I am not sure that he was ever such a Stakhanovite that when he had something urgent to convey he wouldn’t have stopped working to convey it. The earliest communications would in any case have almost certainly been emotive in content—intended to convey anger, warning, threat, appeasement, or sexual desire, and it is unlikely that under the spur of any of these he would have carried on knapping his flints and simply vocalized about them.

Corbyn

by

Richard Seymour

The Telegraph for its part began to intersperse its online pieces about the leadership challenge with a video segment titled ‘Angela Eagle MPs’ best moments’. In a profile box, it affirmed that her ‘reputation as a fierce public debater with a quick wit helped her become the unity candidate’.24 The Guardian offered both Angela Eagle and her sister, Maria Eagle, a predictably soft-soap interview, accentuating their ‘working-class roots, their Stakhanovite work ethic and self-confidence to spare’.25 The Mirror carolled her virtues as a ‘unity candidate’ who was loyal to her party, had ‘wiped the floor’ with opponents in parliamentary debates, and – crucially – was admired by the Pretenders’ Chrissie Hynde.26 ‘Eagle Dares’, the Sun exulted, quoting a number of MPs supporting her stance and none of her critics.

The Man Who Loved China: The Fantastic Story of the Eccentric Scientist Who Unlocked the Mysteries of the Middle Kingdom

by

Simon Winchester

Published 1 Jan 2008

Despite Needham’s occasional air of autocratic disdain, people were eternally eager to help him, support him, and surround him with care. He employed a woman whom he called Auntie Violet to make him breakfast and tea: she worked for him, buttering the crumpets he liked to toast on his electric fire, until she was well over ninety. And once it was realized that even a Stakhanovite like Needham could be tempted to join others for afternoon tea, a variety of distinguished men and women, crumpet lovers and tea drinkers all, would stop by to dine informally with him, often memorably. One professor stopped in to talk about rain gauges—whereupon Needham discovered for him, quite accidentally, a reference to what turned out to be the first rain gauge ever made, in a book on mathematics in the Yuan dynasty.

Careless People: A Cautionary Tale of Power, Greed, and Lost Idealism

by

Sarah Wynn-Williams

Published 11 Mar 2025

Marne’s work ethic sets the rhythm of my life, and it’s unlike anything I’ve experienced before—even in the corporate law firms I worked at. Unlike senior diplomats who, in my experience, were often more grandees wanting to bless the work done by the team beneath them, Marne is a true Facebook Stakhanovite. Her ferocious work ethic and endurance are astounding. To me it seems her emotions, instincts, and physical needs are all sublimated into her job. A numb efficiency ruled by all-consuming self-discipline and self-denial. After a full day’s work without break, Marne will regularly continue at home until the small hours of the morning, rising before 5:00 A.M. to begin work again before exercising.

Radical Technologies: The Design of Everyday Life

by

Adam Greenfield

Published 29 May 2017

What we will discover, I think, is that we urgently need to reinvent (particularly, but not just) a left politics whose every fundamental term has been transformed: a politics of far-reaching solidarity, capable of sustaining and lending nobility to all the members of a near-universal unnecessariat. But we will also discover something else. We needed work, though not in any hackneyed dignity-of-labor sense. We certainly didn’t need to rouse ourselves to Stakhanovite exertions on behalf of uncaring employers; we didn’t benefit from being forced to simulate team-spiritedness, amidst all the profoundly dispiriting banality of our fluorescent-lit cubicles; and it goes without saying we didn’t need to suffer the insults of cretinous customers, working out their neuroses and class frustrations across the counter.

The Establishment: And How They Get Away With It

by

Owen Jones

Published 3 Sep 2014

But in an attempt to contradict his further claim that ‘all writers are vain, selfish and lazy’, I want to make clear that this struggle was far from my own: all books are collective efforts, and this one is far from an exception. Firstly, a very special thanks to my editor, Tom Penn. Tom edited my first book, Chavs, and ensured it was a success, but his efforts in editing this book have been truly Stakhanovite. He hammered the text into shape, challenged and prodded me, and often seemed to know what I was trying to say better than myself. Then there’s my brilliant agent, Andrew Gordon. I owe everything to Andrew: he inexplicably took a punt on me, dragged me from obscurity, and gave me the chance to be a writer.

The Human Tide: How Population Shaped the Modern World

by

Paul Morland

Published 10 Jan 2019

Aaron Soltz, an Old Bolshevik and sometimes referred to as the conscience of the Party, insisted that in the new ‘Socialist Reality’, abortion was no longer required: ‘Our life becomes more gay, more happy, rich and satisfactory. But the appetite, as they say, comes with the meal. Our demands grow from day to day. We need new fighters… We need people.’ He talked of ‘the greatest happiness of motherhood’. Others compared mothers to Stakhanovite workers and justified punishment for abortion on the grounds of the need to ‘protect the health of women’ and ‘safeguard the rearing of a strong and healthy younger generation’.54 Yet despite the newly minted pro-natalism of its Communist leadership, Russia’s fertility rate continued to fall. The human tide could not even be held back by Stalin ‘the Great Architect’, and it turned out it was easier to determine the output of steel or tractors than of children.

When Einstein Walked With Gödel: Excursions to the Edge of Thought

by

Jim Holt

Published 14 May 2018

(Though elementary in appearance, elliptic curves turn out to have a deep structure that makes them endlessly interesting.) He has spent much of his research career in Paris, and it shows; his memoir is full of Gallic intellectual playfulness, plus references to figures like Pierre Bourdieu, Issey Miyake, and Catherine Millet (“the sexual Stakhanovite”) and mention of the endless round of Parisian champagne receptions where “mathematical notes are compared for the first glass or two, after which conversation reverts to university politics and gossip.” It is rambling, sardonic (the term “fuck-you money” appears in the index), and witty. It contains fascinating literary digressions, such as an analysis of the occult mathematical structure of Thomas Pynchon’s novels, and lovely little interludes on elementary math, inspired by Harris’s gallant attempt to explain number theory to a British actress at a Manhattan dinner party.

The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test

by

Tom Wolfe

Published 1 Jan 1968

... That shakes them up all over again in Haight-Ashbury, there's no getting around that. A whole new inflammation of paranoia. The lunger heads are slithering up and down the store fronts on Haight Street. They're hunkered down gabbling in the India-print living rooms. The whole thing takes a Stakhanovite left turn. Kesey is not a right deviationist but a left deviationist. He's not going to cop out by telling the kids to stop taking LSD, that's just the cover story. Instead he's going to pull a monster prank that will wreck the psychedelic movement once and for all... Well, the acid heads in Haight-Ashbury are like a tribe in one respect, anyway, I can see that.

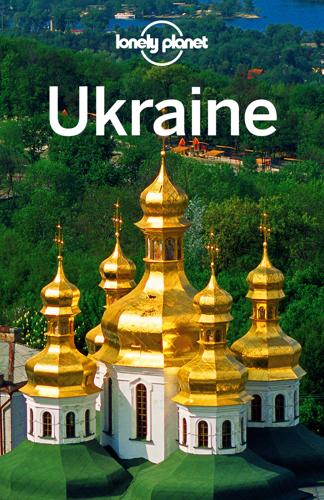

Ukraine

by

Lonely Planet

The restaurant often heaves with Uman’s shaven-headed and short-skirted celebrating weddings to a techno beat. Uman Hotel Unrenovated Soviet $ ( 452 632; vul Radyanska 7; r with shared/ private bathroom per person from 50/92uah) You would expect much, much worse from this centrally located Soviet-style hotel. The rooms, while tatty, are well attended to by Stakhanovite maids, the beds aren’t deal-breakers and the communal showers have been spruced up. No breakfast, but still one of Ukraine’s true bargains. Celentano Pizzeria $ (vul Radyanska 15; pizzas around 20uah) Ukraine’s ubiquitous pizza chain is a blessing in restaurant-starved Uman. Kadubok Shynok Ukrainian $ (vul Radyanska 7; mains around 20uah) On the east side of Uman Hotel, this cafe-cum-restaurant serves Ukrainian and Russian classics including tasty borshch.

Land: How the Hunger for Ownership Shaped the Modern World

by

Simon Winchester

Published 19 Jan 2021

The Pentagon decided it could be published only when East Germany’s strategic significance was deemed to be minimal—and that turned out to be in 1966, when just about all involved (Sven Hedin included) were dead. Slowly, slowly, the stack of completed maps increased. The Soviets changed their mind, and as part of Stalin’s third Five Year Plan agreed to map the entirety of the USSR—it would take fully 182 sheets—starting in 1940. Stakhanovite labors ensued: the venture was completed—despite the many depredations of war—in 1946, with as a result a further 22 million square kilometers of the world’s land surface was added to the accumulating total. The planet’s entire land surface area runs to 37 billion acres: the Soviet Union’s share was some 6 billion, now all of it fully mapped.

The World for Sale: Money, Power and the Traders Who Barter the Earth’s Resources

by

Javier Blas

and

Jack Farchy

Published 25 Feb 2021

(In fact, Strothotte owned one that he leased to the company, and Kazzinc, a Glencore subsidiary, owned another.) 21 And, for Glasenberg, work was everything: on weekends, bored, he was known to call up colleagues to meet up and talk business. Glasenberg was of a different background and generation to Marc Rich, but the two men were similar in many ways. They shared a passion for the business of commodity trading that eclipsed every other aspect of their lives, a Stakhanovite work ethic that put all others to shame, and a personal style that relied on force of will rather than charm. Glasenberg, an early riser, would greet colleagues arriving at Glencore’s headquarters at 8.30 a.m. with a sarcastic ‘good afternoon’. 22 It was the very same joke that Rich had made, several decades earlier, to his colleagues at Philipp Brothers in New York.

Visions of Inequality: From the French Revolution to the End of the Cold War

by

Branko Milanovic

Published 9 Oct 2023

According to him, “the ‘equalizing’ character of wages, destroying personal interestedness, became a brake upon the development of the productive forces.” Leon Trotsky, The Revolution Betrayed: What Is the Soviet Union and Where Is It Going? trans. Max Eastman (Garden City, NY: Doubleday Doran, 1937), 112. Somewhat inconsistently, however, Trotsky in the same book criticized too much emphasis on piecework and the high salaries of Stakhanovite workers, whom he described as a new “workers’ aristocracy” (124). 24 . Joseph V. Stalin, “New Conditions—New Tasks in Economic Construction: Speech Delivered at a Conference of Business Executives June 23, 1931,” in J. V. Stalin, Works, vol. 13 (Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing, 1954), 58–59. 25 .

The Best Business Writing 2013

by

Dean Starkman

Published 1 Jan 2013

Today TED is an insatiable kingpin of international meme laundering—a place where ideas, regardless of their quality, go to seek celebrity, to live in the form of videos, tweets, and now e-books. In the world of TED—or, to use their argot, in the TED “ecosystem”—books become talks, talks become memes, memes become projects, projects become talks, talks become books—and so it goes ad infinitum in the sizzling Stakhanovite cycle of memetics, until any shade of depth or nuance disappears into the virtual void. Richard Dawkins, the father of memetics, should be very proud. Perhaps he can explain how “ideas worth spreading” become “ideas no footnotes can support.” The Khannas’ book is not the only piece of literary rubbish carrying the TED brand.

A Gentleman in Moscow

by

Amor Towles

Published 5 Sep 2016

At the same time, the most stalwart workers in the urban centers were wearying under the burden of the continuous workweek; artists faced tighter constraints on what they could or could not imagine; churches were shuttered, repurposed, or razed; and when revolutionary hero Sergei Kirov was assassinated, the nation was purged of an array of politically unreliable elements. But then, on the seventeenth of November 1935, at the First All-Union Conference of Stakhanovites, Stalin himself declared: Life has improved, comrades. Life is more joyous. . . . Yes, generally speaking such a remark falling from the lips of a statesman should be swept from the floor with the dust and the lint. But when it fell from the lips of Soso, one had good reason to lend it credence.

When They Go Low, We Go High: Speeches That Shape the World – and Why We Need Them

by

Philip Collins

Published 4 Oct 2017

He had studied Cicero and Aristotle and he decided, to use the latter’s term, to be forensic in the military detail he offered. Large sections of this speech are the work of an expressive war reporter. We know from the transcript now held at Churchill College, Cambridge, that he sweated over this text, as he did with all his speeches. Churchill was a Stakhanovite labourer, whose methods of composition were eccentric. For weeks he would try out phrases at dinner, interrupting conversations to sound out the rhythm of a new witticism. He would write while on the telephone, circling the Great Hall at Chequers, propped up in bed or looking at maps of the conflict.

The War Came to Us: Life and Death in Ukraine

by

Christopher Miller

Published 17 Jul 2023

Originally founded by serfs in the late eighteenth century as Oleksiyivka and renamed Chystyakove nearly a century later, the Soviets renamed it a third time in 1964, in honor of the French Communist Party leader Maurice Thorez shortly after his death that year. Most notably, it was here in August 1935 that the Donbas’ most famous miner, Aleksey Stakhanov, is said to have mined a record 102 tons of coal in under six hours, igniting an industrial boom known as the Stakhanovite movement that over the next 40 years brought a flood of mining and manufacturing jobs to the region. His face even graced the cover of Time magazine in December that year and was profiled in a story titled “Stakhanovism’s Great Stakhanov.” Coal forged the Donbas into an industrial Mecca in the decades that followed, with Torez at its center.

To Save Everything, Click Here: The Folly of Technological Solutionism

by

Evgeny Morozov

Published 15 Nov 2013

Want me to prove I will be a diligent, responsible employee? Let me share with you my real time blood alcohol content, how carefully I manage my diabetes, or my lifelong productivity records.” In other words, there are very good reasons why those with excellent health, impressive driving habits, and Stakhanovite productivity will be excited to track and share their data. But what about the poor and the sick? What about those who don’t have the time or the stamina—which those who work three daily jobs to stay afloat might lack—to engage in self-tracking? And what if the poor and the sick do embrace self-monitoring?

Why the Allies Won

by

Richard Overy

Published 29 Feb 2012

Every factory had its small assembly place, the wooden stage and the dais where the plant managers announced the roll of honour for the over-achievers and castigated slackers in front of their workmates.24 Every worker knew the name of the legendary steel-worker Bosyi who arrived in Nizhny Tagil from Leningrad in 1941 where he proceeded to produce his five-month quota in fifteen days. Bosyi got the State Prize. The spirit of what was known as ‘socialist emulation’ spread throughout the economy, echoing the Stakhanovite movement of the 1930s when incentives had been given to workers to exceed work norms by a wide margin. The women tractor drivers got their own hero, driver Garmash, whose team completed a year’s ploughing by June through the simple expedient of keeping the tractor shifts going for over twenty hours a day.25 No doubt the competitive pride that fuelled the emulation programme owed a good deal to official encouragement.

Under the Loving Care of the Fatherly Leader: North Korea and the Kim Dynasty

by

Bradley K. Martin

Published 14 Oct 2004

A new law set standard working hours and mandated sexual equality in pay levels. Kim’s government proceeded with Soviet-style economic planning from 1947. Soviet assistance poured in. The regime called upon the hard work and enthusiasm of those subjects who felt grateful for the end of the old order and the dawn of the new. Stakhanovite campaigns urged industrial workers to sacrifice for productivity. One highly publicized group of locomotive factory workers marched off as “storm-troopers” and reopened an abandoned coal mine, to cope with a coal shortage that was keeping trains from running. A campaign exhorted farmers to turn over portions of their rice harvests for “patriotic” use in emulation of a farmer named Kim Je-won; he supposedly had been so moved by land reform that he donated thirty bales out of his rice harvest, leaving only enough to feed his family for the following year.46 Kim Il-sung traveled far and wide to give “on-the-spot guidance” to his subjects.

…

“Already his eyes saw the splendid, the magnificent streets extending one beyond the other, … the beautiful parks where children frolicked and cultural institutions of marble and granite stood.”12 When the time came to transform the vision into reality, Kim turned the capital’s reconstruction into a nationwide “battle,” in the Soviet Stakhanovite pattern, with college students and office workers pressed into service to keep the building sites humming day and night.13 Other “battles” ensued, to rebuild factories and transportation facilities as Pyongyang fully nationalized the country’s industry. Clearing away the ashes and ruins of war, North Koreans laid an impressive base for economic development. between 1954 and 1958, Pyongyang reported that combined output from mining, manufacturing and power transmission increased more than threefold.14 Industry’s role in generating national income rapidly outdistanced that of agriculture—a key indication of industrial development.15 between 1947 and 1967, per capita income was reported to have grown at an average rate of 13.1 percent a year.16 Other communist countries helped, but there is a debate whether that help came in the philanthropic form of foreign aid or in simple trade and investment.

Enemies and Neighbours: Arabs and Jews in Palestine and Israel, 1917-2017

by

Ian Black

Published 2 Nov 2017

When an Israeli sociologist embarked in the early 1980s on a project to document Palestinians employed inside the green line it opened his eyes to what he and most other Jews had long preferred not to notice: Suddenly I see Palestinian workers everywhere in Tel Aviv, on building sites, in hospitals, at the university of Tel Aviv, in my own department, at restaurants, shops … suddenly I see that other people, like myself before the survey, do not see all this; they do not see that at night the campus [of TAU] is like a big dormitory for Palestinian workers spending the night in TA, and so are the basements of hospitals, shops, warehouses, the food market areas of the city, the beach in summertime, the space underneath Kikar Dizengoff – Tel Aviv’s central piazza; suddenly I realise that people are not only blind to all this, but that they do not want to look at it, even when their attention is drawn to it.41 The prevalence of Palestinian labour a decade after the watershed of 1967 gave rise to wry jokes about what this meant for Israeli society and its values: one featured an elderly Jewish man, reminiscing to his increasingly wide-eyed grandson about his youth as a pioneer, a Zionist Stakhanovite tilling the fields, toiling on construction sites, draining swamps and making the desert bloom from dawn till dusk. ‘Gosh granddad, that’s amazing,’ replied the astonished child. ‘So when you were young, were you an Arab?’ 14 1977–1981 ‘No more war, no more bloodshed.’ Anwar al-Sadat1 JOURNEY TO JERUSALEM In November 1977 Anwar Sadat flew from Cairo to Tel Aviv and then travelled on by road to Jerusalem.

Austerity Britain: 1945-51

by

David Kynaston

Published 12 May 2008

This was Sir Charles Bartlett, managing director from 1929 to 1953, a highly intelligent paternalist who liked his workforce to call him ‘The Skipper’. Given considerable autonomy by his American masters, and inheriting a fairly brutal, hire-and-fire regime, he presided through the 1930s and 1940s over a gradual, quiet and almost entirely successful revolution – in which, crucially, workers were treated as human beings rather than Stakhanovite extras in a remake of Metropolis. Bartlett’s approach to industrial relations had several main features: avoiding lay-offs wherever possible, so that the workforce became more stable; paying good wages; using what was known as the Group Bonus System in order to enhance motivation and give the workforce at least a limited sense of control; introducing a profit-sharing scheme; developing an impressive range of social and welfare amenities; and, at the very core of Bartlett’s strategy from 1941, promoting the Management Advisory Committee (to which each area of the factory sent a representative elected by secret ballot) as a forum for meaningful rather than fig-leaf consultation.

Bourgeois Dignity: Why Economics Can't Explain the Modern World

by

Deirdre N. McCloskey

Published 15 Nov 2011

The pursuit of profit—if the profit is not achieved from protections and monopolies supported by the state’s monopoly of violence, monopolies greatly strengthened in socialist or regulatory states—leads to betterment for all, a joy in work serving others, a form of solidarity that has proven superior to Great Leaps Forward or Stakhanovite campaigns organized by Party officials, or for that matter Christian charity. But anyway radical Protestantism affirmed the significance of this-world life and by 1800, for example, was recommending missionary sainthood in aid of the ordinary lives of Africans or Chinese, even among Protestants (the Catholics in the Portuguese, Spanish, and French empires had been doing it for centuries).

The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers: Economic Change and Military Conflict From 1500 to 2000

by

Paul Kennedy

Published 15 Jan 1989

Whatever the reasons for Stalin’s manic, paranoid assault upon so many of his own people, the economic results were serious: “civil servants, managers, technicians, statisticians, even foremen”133 were swept away into the camps, making Russia’s shortage of trained personnel more acute than ever. While the terror no doubt drove many to demonstrate a Stakhanovite loyalty to the system, it also greatly inhibited innovation, experimentation, open discussion, and constructive criticism: “the simplest thing to do was to avoid responsibility, to seek approval from one’s superior for any act, to obey mechanically any order received, regardless of local conditions.”134 It saved one’s skin; but it did not help the growth of a complex economy.