Avogadro Corp

by

William Hertling

Published 9 Apr 2014

Avogadro worked to refine the design, with plans to use the offshore data centers existing for their own operations, and lease cloud computing capacity to commercial customers. Directly in front of Bill, the primary floating barge held what appear to be sixteen standard shipping containers. They had in fact originated as standard shipping containers, but Bill’s team had added a thick layer of weather proofing to protect the sensitive electronics contained within. Of course, these floating data centers had a few problems that got Bill up in the middle of the night. Resiliency to storms was one big issue.

…

Gene’s printed records showed that Gary’s department purchased tremendous quantities of servers, had servers reallocated from other projects, paid for a variety of subcontractors to do programming work, and finally transferred substantial funds to both the ELOPe project and the Offshore Data Center department. “Offshore Data Center department? What do they do?” asked Christine. “They took the data center in a box concept, which is a standard shipping container filled with racks of computers, and put it on a seaworthy barge,” David answered. “Then they connect the data-center-boxes to wave-action electrical generators. The whole thing is connected back to the data grid with fiber optic cables. Avogadro calls them ODCs for short.” “Well, anyone care to guess the third department with the same unusual pattern of purchases?”

The Practice of Cloud System Administration: DevOps and SRE Practices for Web Services, Volume 2

by

Thomas A. Limoncelli

,

Strata R. Chalup

and

Christina J. Hogan

Published 27 Aug 2014

Since many containers can coexist on the same machine, the resulting machine works much like a large hotel that is able to provide for many customers, treating them all the same way, even though they are all unique. * * * Standardized Shipping Containers A common way for industries to dramatically improve processes is to standardize their delivery mechanism. The introduction of standardized shipping containers revolutionized the freight industry. Previously individual items were loaded and unloaded from ships, usually by hand. Each item was a different size and shape, so each had to be handled differently. Standardized shipping containers resulted in an entirely different way to ship products. Because each shipping container was the same shape and size, loading and unloading could be done much faster.

…

A single container might hold many individual items, but since they were transported as a group, transferring the items between modes of transport was quick work. Customs could approve all the items in a particular container and seal it, eliminating the need for customs checks at remaining hops on the container’s journey as long as the seal remained unbroken. As other modes of transportation adopted the standard shipping container, the concept of intermodal shipping was born. A container would be loaded at a factory and remain as a unit whether it was on a truck, train, or ship. All of this started in April 1956, when Malcom McLean’s company SeaLand organized the first shipment using standardized containers from New Jersey (where Tom lives) to Texas.

…

See Packages Software resiliency, 120–121 Software upgrades in design for operations, 36 Solaris containers, 60 Solid-state drives (SSDs) failures, 132 speed, 26 Source control systems, 206 SOX requirements, 43 Spafford, G., 172 Spare capacity, 124–125 load sharing vs. hot spares, 126 need for, 125–126 Spear, S., 172 Special constraints in design documents, 278 Special notations in style guides, 267 Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-phrased (SMART) criteria, 388 Speed importance, 10 issues, 26–29 Spell check services, abstraction in, 24 Spindles, 26 Split brain, 23 Split days oncall schedules, 289 Spolsky, J., 121 Sprints, 189 SQS (Simple Queue Service), 86 SRE (Site Reliability Engineering), 147–148 DevOps, 181 overview, 151–152 vs. traditional enterprise IT, 148–149 SSDs (solid-state drives) failures, 132 speed, 26 Stability vs. change, 149–151 Stack Exchange, 167 Stack ranking, 360 Stakeholders, 148 Standard capacity planning, 366–368 Standardized shipping containers, 62 Startup in design for operations, 34–35 States, distributed, 17–20 Static content on web servers, 70 Status of design documents, 277, 282 Steal time, 59 Stickiness in load balancing, 75 Storage systems, monitoring, 345, 362 Stranded capacity, 57 Stranded resources in containers, 61 Style guides automation, 266–267, 270 code review systems, 269 Sub-linear scaling, 477 Subscribers in message bus architectures, 86 Subsystems, linking tickets to, 263–264 Suggested resolution in alert messages, 355 Summarization, monitoring, 339 Super-linear scaling, 477 Survivable systems, 120 SWEs (software engineers), 199 Synthesized measurements, 347–348 System administration, automating, 248–249, 253 System logs, 340 System testing in build phase, 203 vs. canarying, 228–229 overview, 215 T-bird database system, 103 Tags in repositories, 208 Taking down services for upgrading, 225–226 Targeting in system integration, 250 Tasks assessments, 423–425 automating, 153–155 TCO (total cost of ownership), 172 TDD (test-driven development), 267–268 Team managers in operational rotation, 162 TeamCity tool, 205 Teams, 160–162 automating processes, 155 fix-it days, 166 focus, 165–166 in Incident Command System, 326 oncall days, 163–164 organizing strategies, 160–166 project-focused days, 162–163 ticket duty days, 164–165 toil reduction, 166 virtual offices, 166–167 Technical debt, 166 Technical practices in DevOps, 184–185 Technology cloud computing era, 472 dot-bomb era, 460–461 first web era, 455–456 pre-web era, 453–454 second web era, 465–466 Telles, Marcel, 401 Templates design documents, 279, 282, 481–484 postmortem, 484–485 Terminology for Incident Command System, 324 Test-driven development (TDD), 267–268 Tests vs. canarying, 228–229 continuous deployment, 237 deployment phase, 215–216 DevOps, 186 disaster preparedness.

Empty Vessel: The Story of the Global Economy in One Barge

by

Ian Kumekawa

Published 6 May 2025

There, with great fanfare, she smashed a bottle of champagne against the hull of a brand-new vessel at a Götaverken shipyard in Gothenburg. The vessel that she christened, the Safe Astoria, was not really a ship but instead a floating platform: the first “accommodation platform” ever to be purpose-built. The idea behind the Safe Astoria was simple: to create a floating structure loaded with stacks of standardized shipping containers modified into living space. The Astoria was billed as a “floatel,” a construction that could house hundreds of the oilmen who built, maintained, and worked on the offshore rigs floating on the North Sea.[1] Henderson came to the Götaverken yard because of the economic transformation of the North Sea.

…

Each “toilet/shower module” would have a noncombustible shower curtain, soap holder, toilet paper holder, coat hook, towel holder, mirror, and small cabinet.[50] The accommodation decks themselves were constructed from prefabricated units: what the plans for the refit referred to as “Type 1” and “Type 2” modules. Type 1 modules were slightly modified standard shipping containers: “Standard 20 ISO Cont[ainers].”[51] They were used for the one-person cabins that would house the crew. Type 2 modules were a little larger. These were used for multi-person cabins, showers and toilets, the galley and laundry area, as well as the storerooms. Like the Type 1 containers, they were interchangeable building blocks.

…

In Consafe founder Christer Ericsson’s words, each vessel was “a big shoebox on a barge.”[66] More precisely, they were many boxes on a barge. Like Ericsson’s original innovation of the nylon strap, Consafe’s accommodation vessels emerged directly from the containerization of global trade. As their blueprints make clear, they were simply standard shipping containers welded together into living units.[67] Those units were to be filled by the new cowboys of northern Europe: the offshore roughnecks of the North Sea. * * * • • • Six hundred and fifty miles across the North Sea from Christer Ericsson’s headquarters in Gothenburg, in an office in Liverpool, another corporate executive was closely following the changing economic landscape of offshore oil.

Chokepoints: American Power in the Age of Economic Warfare

by

Edward Fishman

Published 25 Feb 2025

In Britain, Margaret Thatcher’s government went so far as to destroy official files on capital controls so that successors would struggle to reimpose them. In the United States, Ronald Reagan deregulated vast parts of the financial industry and created gaping budget deficits by slashing taxes at the same time as he boosted military spending. These policies created conditions under which new technologies—the computer, the standardized shipping container, and eventually the internet—could knit together the global economy into one giant web, and they granted Thatcher and Reagan admission into the neoliberal pantheon. But in the United States, in particular, neoliberalism’s ascendancy started before Reagan entered the White House, and it crested well after he departed.

…

In finance, the growth of the Eurodollar market helped precipitate the end of capital controls, which in turn led banks to create new technologies for cross-border finance, including CHIPS (the world’s leading system for settling payments) and the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunications, or SWIFT (a messaging service for banks that became a lingua franca for international finance). In trade, the emergence of the standardized shipping container and just-in-time manufacturing allowed firms to capitalize on lower tariff barriers negotiated under the auspices of NAFTA and the WTO. Time and again, removing obstacles to cross-border economic activity created demand for new technologies that would help conduct such activity, which incentivized additional globalization-friendly policies, and so on.

…

GO TO NOTE REFERENCE IN TEXT finance, including CHIPS: “About CHIPS,” The Clearing House, www.theclearinghouse.org/payment-systems/chips. GO TO NOTE REFERENCE IN TEXT a lingua franca: Henry Farrell and Abraham Newman, Underground Empire: How America Weaponized the World Economy (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2023), 26–28. GO TO NOTE REFERENCE IN TEXT of the standardized shipping container: Marc Levinson, The Box: How the Shipping Container Made the World Smaller and the World Economy Bigger (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2006), 355–56. GO TO NOTE REFERENCE IN TEXT world’s largest single market: “From 6 to 27 Members,” European Commission, February 1, 2020, neighbourhood-enlargement.ec.europa.eu/enlargement-policy/6-27-members_en; “Towards Open and Fair World-wide Trade,” European Union, european-union.europa.eu/priorities-and-actions/actions-topic/trade_en.

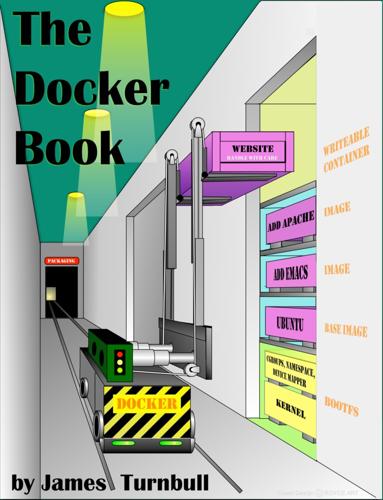

The Docker Book

by

James Turnbull

Published 13 Jul 2014

As we've just learned, containers are launched from images and can contain one or more running processes. You can think about images as the building or packing aspect of Docker and the containers as the running or execution aspect of Docker. A Docker container is: An image format. A set of standard operations. An execution environment. Docker borrows the concept of the standard shipping container, used to transport goods globally, as a model for its containers. But instead of shipping goods, Docker containers ship software. Each container contains a software image -- its 'cargo' -- and, like its physical counterpart, allows a set of operations to be performed. For example, it can be created, started, stopped, restarted, and destroyed.

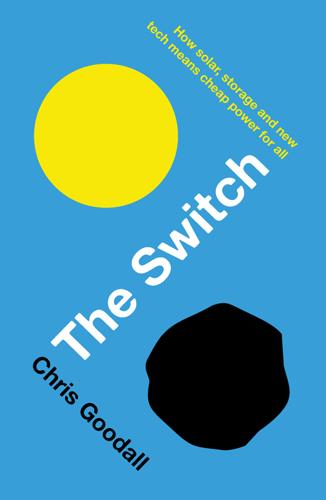

The Switch: How Solar, Storage and New Tech Means Cheap Power for All

by

Chris Goodall

Published 6 Jul 2016

In countries such as Kenya that will get most of their power from PV, biomass can be a perfect complement to the daily variability of solar electricity. Dry biomass: Entrade In June 2015 I went up to Cheshire, in the north of England, to see one of the world’s first commercial small scale biomass gasifiers. Sitting inside a standard shipping container, the Entrade E3 plant from Germany takes in small pellets of woody biomass and heats them in the absence of air to several hundred degrees. At the right temperature, these pellets turn into hydrogen and carbon monoxide (‘syngas’) and this combination can be burnt in a gas turbine to generate electricity.

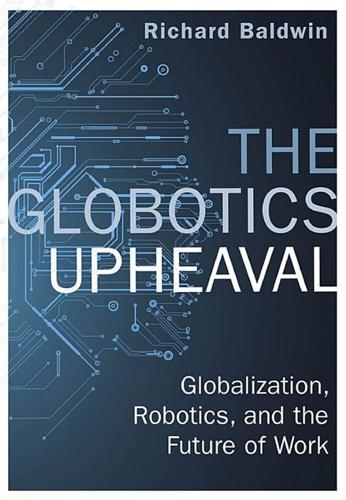

The Globotics Upheaval: Globalisation, Robotics and the Future of Work

by

Richard Baldwin

Published 10 Jan 2019

It was called “featherbedding” and forced companies to keep paying workers whose jobs had been rendered obsolete by automation. This seems destined to be copied in future shelterism. Containerized shipping was a boon to trade and manufacturing from the 1960s. Shipping costs were slashed by the switch to standardized shipping containers that could be loaded and unloaded directly from trains or trucks with massive cranes. The labour-and time-saving technology, however, scuppered the fortunes of highly paid dock workers known as longshoremen, who loaded and unloaded ships using traditional methods. Ultimately, it was a question of who would bear the economic and social costs of technological change: the workers or the companies.

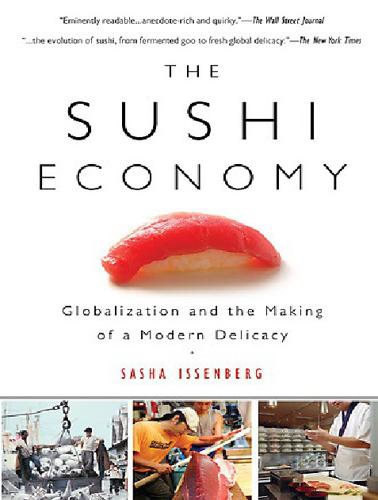

The Sushi Economy: Globalization and the Making of a Modern Delicacy

by

Sasha Issenberg

Published 1 Jan 2007

Unlike previous passenger planes, the 747 was also designed with freight in mind. What some describe as a roomier interior—the familiar two-aisle arrangement, and its attendant five-seat middle block, home to the most undesirable middle seat possible— was really the consequence of building a hold wide enough for two standard shipping containers to sit side by side. The struggle to build the 747 nearly bankrupted not only Boeing (“within a gnat’s whisker,” its president said) but the company town in which it was based, so much so that Seattle’s Japanese sister city Kobe sent relief supplies of food and money in 1968. A year earlier, JAL had been one of the first airlines to place an order for three 747s, and three years later introduced them on Pacific routes.

Frugal Innovation: How to Do Better With Less

by

Jaideep Prabhu Navi Radjou

Published 15 Feb 2015

Fablabs and TechShops: DIY micro-factories that make anything Conceived and launched by Neil Gershenfeld, a professor at MIT, a Fablab is a digital fabrication workshop, fully equipped with CNC machines, laser cutters and 3D printers, which is free and open to the public to tinker and make “almost anything”. A Fablab has been described as a “factory in a box”. Indeed, Fablabs’ contents fit into a standard shipping container, allowing them to be easily transported and installed in any city around the world. There are currently more than 125 Fablabs in 34 countries. TechShops are an advanced version of Fablabs where, for a $175 monthly fee, users get access to heavy-duty equipment for making industrial-calibre products.

The Great Surge: The Ascent of the Developing World

by

Steven Radelet

Published 10 Nov 2015

Just as the industrial revolution can be traced to James Watt’s invention of the steam engine, which drove innovations and changes across the economic landscape, much of the current technological revolution can be traced back to the semiconductor and the computer, a history that Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee recount in The Second Machine Age: Work, Progress, and Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies.14 There are multiple examples, but I will focus on technological advances in four areas that have been important to developing countries: transportation, agriculture, information, and health. MOVING GOODS, MOVING PEOPLE The most important development in integrating global trade during the last century was not the World Trade Organization (WTO) or global trade agreements or lower tariffs. The most important development was a box: a standardized shipping container. Up until the 1950s, goods were loaded and unloaded onto ships in individual boxes, barrels, sacks, and wooden crates, a process that was slow, cumbersome, and expensive, and resulted in a high rate of damaged goods and very inefficient use of space. An entrepreneur named Malcolm McLean developed an idea of how it could be done better.

Arriving Today: From Factory to Front Door -- Why Everything Has Changed About How and What We Buy

by

Christopher Mims

Published 13 Sep 2021

As Marc Levinson recounts in The Box, his obsessively detailed history of the shipping container, “It took a major war, the United States’ painful campaign in Vietnam, to prove the merit of this revolutionary approach to moving freight.” Until that war, containerized shipping as we know it today, with all its interdependencies of ships, cranes, docks, trucks, railroad cars, and countless other bits of equipment, all built to accommodate standardized shipping containers, was proving nearly impossible to jump-start. Everything was a chicken-and-egg problem—huge investments in onshore cranes couldn’t be justified without equally enormous investments in the proper ships. And it was compounded by a collective-action problem—the commercial interests of a variety of companies all wanting their size and type of shipping container to become the standard.

Seasteading: How Floating Nations Will Restore the Environment, Enrich the Poor, Cure the Sick, and Liberate Humanity From Politicians

by

Joe Quirk

and

Patri Friedman

Published 21 Mar 2017

“Just as you can download apps on your smartphone according to your changing needs,” said Koen in his interview with the blog Inhabitat, “you can adjust functionality in a slum by adding functions with city apps. These are floating developments based on standard sea-freight containers, and because of their flexibility and small size, they are suitable for installing and upgrading sanitation, housing, and communication.” Koen has already transformed a standard shipping container into a sleek school classroom fitted with twenty computer screens and two large TV screens featuring a teacher. Painted on the side of the floating school is “City App,” the first demonstration of what Koen hopes will be a humanitarian delivery system. As we write, Dutch children enjoy it where it sits next to Koen’s office, which means it will probably pass muster among curious slum children.

The World in 2050: Four Forces Shaping Civilization's Northern Future

by

Laurence C. Smith

Published 22 Sep 2010

Merchant capitalism flourished, fueled by furs, timber, gold, spices, and coal imported from overseas. Guided by multinational banks, by the 1870s goods and capital were flowing across national borders as freely as they do today. Steamships, the telegraph, and railroads were opening up the world just as standardized shipping containers, jet aircraft, and the Internet would do again a century later. Many countries decided to peg their paper currencies to a gold standard, creating fluid international currency markets and huge flows of cross-border capital. The British pound became the dominant circulating world currency much as the U.S. dollar is now.

Blockchain Revolution: How the Technology Behind Bitcoin Is Changing Money, Business, and the World

by

Don Tapscott

and

Alex Tapscott

Published 9 May 2016

Moving Value: Daily, the financial system moves money around the world, making sure that no dollar is spent twice: from the ninety-nine-cent purchase of a song on iTunes to the transfer of billions of dollars to settle an intracompany fund transfer, purchase an asset, or acquire a company. Blockchain can become the common standard for the movement of anything of value—currencies, stocks, bonds, and titles—in batches big and small, to distances near and far, and to counterparties known and unknown. Thus, blockchain can do for the movement of value what the standard shipping container did for the movement of goods: dramatically lower cost, improve speed, reduce friction, and boost economic growth and prosperity. 3. Storing Value: Financial institutions are the repositories of value for people, institutions, and governments. For the average Joe, a bank stores value in a safety deposit box, a savings account, or a checking account.

Moby-Duck: The True Story of 28,800 Bath Toys Lost at Sea and of the Beachcombers, Oceanographers, Environmentalists, and Fools, Including the Author, Who Went in Search of Them

by

Donovan Hohn

Published 1 Jan 2010

The China was a C-11-class post-Panamax ship, meaning that—at 906 feet long and 131 feet wide—it was too big for the locks of the Panama Canal. Standing on a dock beside it, you would have felt as though you were standing at the foot of an unnaturally smooth cliff, a palisade of steel. The carrying capacity of a container ship is measured in TEUs, or twenty-foot-equivalent units, because a standard shipping container is twenty feet long. One twenty-footer equals one TEU, a forty-footer, two. The China had a carrying capacity of 4,832 TEUs. (That of the Evergreen Ever Laurel, by contrast, was a mere 1,180 TEUs.) Imagine a train pulling 4,832 boxcars: it would stretch for nineteen miles, from the southern tip of Manhattan up into Westchester.

Dark Mirror: Edward Snowden and the Surveillance State

by

Barton Gellman

Published 20 May 2020

He regularly sat down with chiefs and deputy chiefs of the CIA’s technical branches, representing Dell in meetings with Jeanne Tisinger, the CIA’s chief information officer, and Ira “Gus” Hunt, the agency’s chief technology officer. Hunt liked to brainstorm, and Snowden told me he pitched one blue sky proposal after another. How about a self-contained, globally deployable data center, sized to fit a standard shipping container? How about a network switch with built-in “separation kernels,” or secure hardware enclaves, to guard the digital boundaries between differently classified data flows? Snowden’s career seemed to be thriving, but he was already looking for a change. Interesting problems, the kind that combined technical and operational challenges, attracted him more than access to the executive suites at Dell and its client agencies.

The Dead Hand: The Untold Story of the Cold War Arms Race and Its Dangerous Legacy

by

David Hoffman

Published 1 Jan 2009

Declassified in part to author Sept. 22, 2006, under FOIA. 9 Burns, interview, Aug. 12, 2004. 10 "Delegation on Nuclear Safety, Security and Dismantlement (SSD): Summary Report of Technical Exchanges in Albuquerque, April 28--May 1, 1992," State Department cable. 11 Note made by a participant who asked to remain anonymous, undated. 12 Keith Almquist, communications with author, Dec. 14, 2008, and Jan. 24, 2009. Later, Sandia procured materials for another ninety-nine upgrades and sent these in standard shipping containers to a Russian rail car factory in Tver, Russia, and then contracted with the factory to do the conversions. The upgrades involved changing the insulation and locking down the movable platform. Sandi also provided alarm-monitoring equipment. Some older Russian rail cars were made of wood.

The Outlaw Ocean: Journeys Across the Last Untamed Frontier

by

Ian Urbina

Published 19 Aug 2019

This military presence allowed for more efficient deployments of sniper teams, coordination of ransom payoffs, and safe evacuations during hostage situations. Complicating matters further, the shipping industry reacted in its own way, and the economics of that response was at times perverse. For example, freight companies and their insurers began imposing piracy fees—upwards of $23 per standard shipping container—to cover additional security costs, which on bigger ships could mean a quarter of a million dollars per trip. Even factoring in the cost of private guards and the occasional multimillion-dollar ransom payouts exacted by pirates, shipping companies and crews were sometimes profiting from the threat of Somali piracy.