stochastic parrot

description: metaphor to describe the theory that large language models, though able to generate plausible language, do not understand the meaning of the language they process

generative artificial intelligence

18 results

The Means of Prediction: How AI Really Works (And Who Benefits)

by Maximilian Kasy · 15 Jan 2025 · 209pp · 63,332 words

a similar vein, Timnit Gebru, a computer scientist writing during her time working at Google, warned of the dangers of large language models acting as stochastic parrots, which repeat language patterns without understanding, and in doing so replicate the biases embedded in their training data. Meredith Whittaker, currently the president of the

…

it will be worth the effort. References Part I: Introduction Bender, E. M., T. Gebru, A. McMillan-Major, and S. Shmitchell. “On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big?” Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, 2021, 610–23. Benjamin, R. “Assessing Risk, Automating

Why Machines Learn: The Elegant Math Behind Modern AI

by Anil Ananthaswamy · 15 Jul 2024 · 416pp · 118,522 words

still nothing more than sophisticated pattern matching. (Emily Bender of the University of Washington and colleagues coined a colorful phrase for LLMs; they called them “stochastic parrots.”) Others see glimmers of an ability to reason and even model the outside world. Who is right? We don’t know, and theorists are straining

…

, “ChatGPT and Its Ilk,” YouTube video, n.d., https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gL4cquObnbE. GO TO NOTE REFERENCE IN TEXT “stochastic parrots”: Emily M. Bender et al., “On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big?” FAccT ’21: Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, Association

These Strange New Minds: How AI Learned to Talk and What It Means

by Christopher Summerfield · 11 Mar 2025 · 412pp · 122,298 words

rulebook, without ever grasping their meaning. Many people have found this to be a compelling metaphor for LLMs. One highly influential paper describes LLMs as ‘stochastic parrots’ – where ‘stochastic’ indicates that they encode probabilities of transitions between words.[*5] An LLM is, the authors argue, a system for ‘haphazardly stitching together sequences

…

decipher (who will never be able to make polite chit-chat with the Pope). So, although it is a witty rebuke, LLMs are not just ‘stochastic parrots’. They resemble parrots in that any words they use are ultimately copied from humans. But humans also learn language from other humans, so this is

…

not a computational neuroscientist, somehow sensed this when, a few days after ChatGPT was released to tremendous fanfare in 2022, he tweeted: ‘I am a stochastic parrot and so r u.’ Which, despite being slightly facetious and snide, is entirely correct in implying that prediction is the shared computational basis for learning

…

talking enthusiastically about ChatGPT on national television or in public debates at universities, and even organizing workshops on how to use this stochastic parrot in academic education.[*4] The term ‘stochastic parrot’ is, of course, a reference to the famous paper, discussed in Part 3, which argues that claims of LLM capability are massively

…

did not sign the letter were those who dismiss claims of powerful AI as baseless puffed-up bravado. For example, one co-author of the ‘stochastic parrots’ paper was quick to dismiss the letter as ‘dripping with #AIhype…helping those building this stuff sell it’.[*10] In fact, whilst you might think

…

Sciences, 116(32), pp. 15849–54. Available at https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1903070116. Bender, E. M. et al. (2021), ‘On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models be Too Big? ’, Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency. FAccT ’21: 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability

…

, 101, 110, 112, 148–53, 308 statistical patterns, language and, 59, 67, 79–80, 115, 146, 164 stochastic, LLMs designed to be, 142, 333–4 stochastic parrots, LLMs as, 150, 151, 161, 162, 308, 311 Stockfish, 274–6 Stratego, 43 Sutskever, Ilya, 19, 101n, 122, 346 Sutton, Rich, 305–6, 310 Swift

…

people and LLMs and, 47, 121–4, 133–5, 227–31, 237, 260, 284, 335, 237 statistical models, damning LLMs as merely, 148–53, 308 stochastic parrots, LLMs as, 150, 151, 161, 162, 308, 311 thoughts, generation of, 278, 279, 281, 293 Tōhoku earthquake, Japan (2011), 323 tokens, 50, 53, 98–9

Empire of AI: Dreams and Nightmares in Sam Altman's OpenAI

by Karen Hao · 19 May 2025 · 660pp · 179,531 words

two days, Bender had sent Gebru an outline. They later came up with a title, adding a cheeky emoji for emphasis: “On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big? “” * * * — Gebru assembled a research team for the paper within Google, including her colead Mitchell. In response to the encouraging

…

a competent adviser, a trustworthy confidant, and perhaps even something sentient. In November, per standard company protocol, Gebru sought Google’s approval to publish the “Stochastic Parrots” paper at a leading AI ethics research conference. Samy Bengio, who was now her manager, approved it. Another Google colleague reviewed it and provided some

…

control these technologies; and the lack of employee protections against forceful and sudden retaliation if they tried to speak out about unethical corporate practices. The “Stochastic Parrots” paper became a rallying cry, driving home a central question: What kind of future are we building with AI? By and for whom? * * * — For Jeff

…

community. After Gebru’s ouster, Dean’s efforts to justify Google’s actions sullied that pristine record. Dean, whom Kacholia reported to, told colleagues the “Stochastic Parrots” paper “didn’t meet our bar for publication,” holding fast to that characterization even after the paper passed peer review and was published at a

…

Search. But what seemed to bother Dean the most was how other people had misread Strubell’s research to make Google look significantly worse. The “Stochastic Parrots” paper, Dean argued, risked exacerbating this issue. Because Gebru did have access to Google’s internal numbers and was citing Strubell’s external estimate anyway

…

with The Washington Post. Nitasha Tiku, the reporter who broke the story, also spoke to Emily Bender and Meg Mitchell, who had warned in their “Stochastic Parrots” paper about the problem of large language models fooling people into seeing real meaning and intent behind their generations. “We now have machines that can

…

yet, in the very same moment, corporate obfuscation of that impact has reached new heights. Since Emma Strubell’s paper and Gebru’s citation in “Stochastic Parrots,” tech giants have hidden away even more of their models’ technical details, making it exceedingly hard to estimate and track their carbon footprints. At the

…

the whole world is not getting a chance to impact tech,” she says. Alex Hanna, a sociologist and one of the Google coauthors on the “Stochastic Parrots” paper, became the first to join Gebru as DAIR’s director of research. Hanna’s first order of business was to write a research philosophy

…

.acm.org/doi/abs/10.5555/3495724.3495883. GO TO NOTE REFERENCE IN TEXT Gebru chimed in: The account of Gebru’s experiences around the “Stochastic Parrots” paper comes primarily from author interviews with Gebru, 2020–24, including one day after her ouster, as well as a detailed account in Tom Simonite

…

REFERENCE IN TEXT In total, it presented four: Emily M. Bender, Timnit Gebru, Angelina McMillan-Major, and Shmargaret Shmitchell [Meg Mitchell], “On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big? “” in FAccT ’21: Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (March 2021): 610–23, doi

…

-Fried, Samuel, 231–32, 233, 257–58, 380 Beckham, David, 1 Bell Labs, 55 Bender, Emily M., 164–69, 253–54 “On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots,” 164–73, 254, 276, 414 Bengio, Samy, 161–62, 165, 166–67, 169 Bengio, Yoshua, 105, 162 Bezos, Jeff, 41 Biden, Joe, 115–16, 310

…

, 153, 253–54 language loss, 409–13 large language models, 15, 71, 115, 133, 153, 156, 158–60 language loss, 410 “On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots,” 164–73, 254, 276, 414 Latitude, 180–81, 189 Lattice, 36 Leap Motion, 69, 150, 344 LeCun, Yann, 105, 159, 235, 305 Leike, Jan, 387

…

Engineering, 121, 411 Olson, Parmy, 18 Ommer, Björn, 236 Omni, 380, 381 Omnicrisis, 390–92, 395–98, 400, 401, 403, 404 “On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots” (Bender), 164–73, 254, 276, 414 OpenAI. See also specific persons and products Altman’s firing and reinstatement, 1–12, 14, 364–73 author’s

AI in Museums: Reflections, Perspectives and Applications

by Sonja Thiel and Johannes C. Bernhardt · 31 Dec 2023 · 321pp · 113,564 words

production as it occurs in the context of large language models such as ChatGPT or GPT-4 is often likened to the figure of the ‘stochastic parrot’ (Bender et al. 2021, 610–23): like a parrot, AI technology is not capable of reflecting on what has been blended together from the data

…

generative AI. Yannick Hofmann and Cecilia Preiß: Say the Image, Don’t Make It References Bender, Emily M. et al. (2021). On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big? In: FACCT Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency. 610–23. https://doi.org/10

The Optimist: Sam Altman, OpenAI, and the Race to Invent the Future

by Keach Hagey · 19 May 2025 · 439pp · 125,379 words

had broken out at Google over the publication of a controversial paper by lead researchers Emily Bender and Timnit Gebru called “On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big?”14 The title’s menacing image of a plumed colossus combines the talking birds’ famous knack for imitation and

…

an uncommon word—“stochastic,” derived from the Greek stokhastikos, which is related to English’s “conjecture.” The phrase “stochastic parrots,” then, refers to the propensity of large language models to produce guesswork and mimicry, as opposed to thoughtful analysis and human communication. The paper goes

…

co-authors to retract it. Gebru claims she was then fired, while Google maintains she resigned.15 The affair exploded into the press and turned “Stochastic Parrots” into one of the most-cited critiques of AI and a cultural meme. (Shortly after OpenAI released ChatGPT the following year, Altman would cheekily tweet

…

, “I am a stochastic parrot and so r u.”)16 But in many ways, the paper validated and gave voice to the sort of fears that Amodei, Brundage, Clark, and

…

was a lightning rod for controversy. In 2020, Timnit Gebru, the well-known AI ethics researcher, said she was fired for refusing to retract the “Stochastic Parrots” paper that raised questions about the risks of large language models like LaMDA. Google claimed she wasn’t fired, and that the paper did not

…

’s Text Generator Is Going Commercial,” Wired, June 11, 2020. 14.Emily M. Bender, Timnit Gebru, Angelina McMillan-Major, Margaret Mitchell, “On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big?” Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, 2021. 15.Emily Bobrow, “Timnit Gebru Is Calling

…

Attention to the Pitfall of AI,” The Wall Street Journal, February 24, 2023. 16.Sam Altman @sama, “I am a stochastic parrot and so r u,” Twitter, December 4, 2022. CHAPTER 15CHATGPT 1.Tom Simonite, “It Began as an AI-Fueled Dungeon Game. It Got Much Darker

…

parable of the paperclip-making AI, 5, 143–44, 164 pedophilia and, 254 Puerto Rico conference on AI safety (2015), 167–70, 207, 211 the Stochastic Parrot critique of AI, 252–53 AI Superpowers (Lee), 267 AIDS crisis, 33, 43, 49 AIM (AOL Instant Messenger), 16, 50, 76, 162 Airbnb, 4, 123

…

, 81, 162 Oklo fission microreactor startup, 13, 137, 280 Olah, Chris, 178, 184 1billionmasks.com, 250 O’Neill, Megan, 28–29 “On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big?” (Bender and Gebru), 252–53 Open Philanthropy Project, 213–14, 241, 266–67, 276–77, 299–301 OpenAI the

Escape From Model Land: How Mathematical Models Can Lead Us Astray and What We Can Do About It

by Erica Thompson · 6 Dec 2022 · 250pp · 79,360 words

model and the definition of adequacy-for-purpose. And this often happens without the makers even realising that any other perspectives exist. Clever horses and stochastic parrots Clever Hans was a performance act at the beginning of the twentieth century, a horse that was able to tap a hoof to indicate the

…

they do not personally affect the majority of these researchers. Linguist Emily Bender, AI researcher Timnit Gebru and colleagues have written about ‘the dangers of stochastic parrots’, referring to language models that can emulate English text in a variety of styles. Such models can now write poetry, answer questions, compose articles and

…

is not. Of course, both Clever Hans and the tank detector were doing interesting things – just not what their handlers thought they were doing. The ‘stochastic parrot’ language models are doing very interesting things too, and their output may be indistinguishable from human-generated text in some circumstances, but that by itself

…

Danger of a Single Story’, TED talk (video and transcript), 2009 Bender, Emily, Timnit Gebru, Angelina McMillan-Major and Shmargaret Shmitchell, ‘On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big?’, Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, 2021 Bolukbasi, Tolga, Kai-Wei Chang, James Y

Supremacy: AI, ChatGPT, and the Race That Will Change the World

by Parmy Olson · 284pp · 96,087 words

the way GPT-3 and other large language models were dazzling their early users with what was, essentially, glorified autocorrect software. So she suggested putting “stochastic parrots” in the title to emphasize that the machines were simply parroting their training. She and the other authors summed up their suggestions to OpenAI: document

…

corporate Gmail account to document discriminatory incidents at the company. Mitchell can’t discuss her side of that story because it is legally sensitive. The Stochastic Parrots paper hadn’t been all that earth-shattering in its findings. It was mainly an assemblage of other research work. But as word of the

…

dozens of articles in newspapers and websites, more than one thousand citations from other researchers, while “stochastic parrot” became a catchphrase for the limits of large language models. Sam Altman would later tweet, “I am a stochastic parrot and so r u” days after the release of ChatGPT. Much as Altman may have been

…

Government Can Do about It.” www.brookings.edu, September 27, 2021. Bender, Emily, Timnit Gebru, Angelina McMillan-Major, and Shmargaret Shmitchell. “On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big?” FAccTConference ’21: Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (March 2021): 610–23. https://dl

…

on Reddit and removal from OpenAI reputation as tech savior and restructuring of OpenAI and “ship it” strategy and Silicon Valley and Stanford University and Stochastic Parrots paper and on threats posed by AI Toner’s paper and transhumanism and Y Combinator and Amazon America Online (AOL), LGBTQ community and Amodei, Daniela

…

on LaMDA and Lemoine and Meena chatbot and Mitchell and Open Research Group personal data principles regarding AI Project Maven and revenue of scale of Stochastic Parrots paper and Street View TPU and transformers and transition to Alphabet transparency issues and word embedding and Google Brain Google Brain Women and Allies group

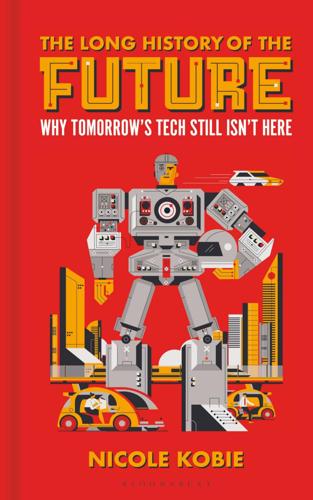

The Long History of the Future: Why Tomorrow's Technology Still Isn't Here

by Nicole Kobie · 3 Jul 2024 · 348pp · 119,358 words

harder to document those data sets or even understand what they contain. A third challenge concerns the very nature of LLMs: the paper dubs them ‘stochastic parrots’, meaning they mimic without understanding. The AI system is not applying meaning, that’s up to readers to do. This is why so many people

…

meaning or context, they merely spit out text that matches the pattern of our language. They do it incredibly well, and it fools us. These stochastic parrots create language without meaning. Any meaning in the output is supplied by the reader, and is therefore an illusion. Bias, strengthening the status quo, misunderstanding

…

Lighthill Controversy Debate, BBC, 1973. https://biturl.top/N7nIje Bender, Emily M.; Gebru, Timnit; McMillan-Major, Angelina; Mitchell, Margaret. ‘Statement from the listed authors of Stochastic Parrots on the “AI pause” letter.’ DAIR Institute, March 31, 2023. https://biturl.top/neqMJr Bender, Emily M.; Gebru, Timnit; McMillan-Major, Angelina; Shmitchell, Shmargaret. ‘On

…

the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big?’ FAccT ’21: Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, March 2021, pp. 610–623. https

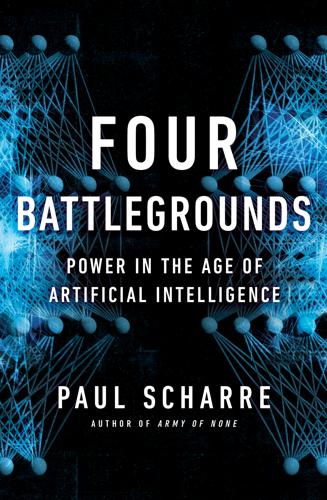

Four Battlegrounds

by Paul Scharre · 18 Jan 2023

-detail/26057. 234gender, racial, and religious biases: Brown et al., Language Models are Few-Shot Learners; Emily M. Bender et al., “On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big?” FAccT ‘21: Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (March 2021), 610–623, https://dl

…

. Bureau of Labor Statistics, updated January 22, 2021, https://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat11.htm. 234existing social biases: Bender et al., “On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots.” 234option to choose the gender: Kuczmarski, “Reducing Gender Bias in Google Translate.” 234résumé-sorting model: Jeffrey Dastin, “Amazon Scraps Secret AI Recruiting Tool That Showed

…

(arXiv.org, January 11, 2021), https://arxiv.org/pdf/2101.03961.pdf. 294745 GB of text: Emily M. Bender et al., “On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big?” FAccT ‘21: Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (March 2021), 610–623, https://dl

…

-goes-brrr-revisiting-suttons-bitter-lesson; Bommasani et al., On the Opportunities and Risks of Foundation Models. 299contributes to carbon emissions: “On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots”; Brooks, “A Better Lesson”; Vu, “Compute Goes Brrr”; Lasse F. Wolff Anthony, Benjamin Kanding, and Raghavendra Selvan, “Carbontracker: Tracking and Predicting the Carbon Footprint of

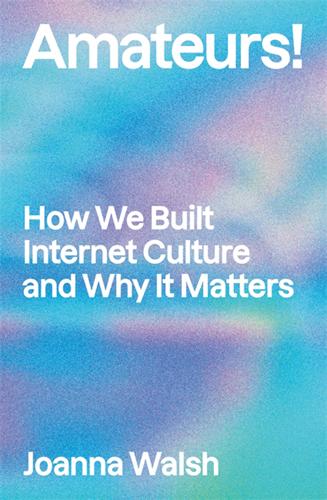

Amateurs!: How We Built Internet Culture and Why It Matters

by Joanna Walsh · 22 Sep 2025 · 255pp · 80,203 words

Searches: Selfhood in the Digital Age

by Vauhini Vara · 8 Apr 2025 · 301pp · 105,209 words

The Shame Machine: Who Profits in the New Age of Humiliation

by Cathy O'Neil · 15 Mar 2022 · 318pp · 73,713 words

Everything Is Predictable: How Bayesian Statistics Explain Our World

by Tom Chivers · 6 May 2024 · 283pp · 102,484 words

The Equality Machine: Harnessing Digital Technology for a Brighter, More Inclusive Future

by Orly Lobel · 17 Oct 2022 · 370pp · 112,809 words

More Everything Forever: AI Overlords, Space Empires, and Silicon Valley's Crusade to Control the Fate of Humanity

by Adam Becker · 14 Jun 2025 · 381pp · 119,533 words

Enshittification: Why Everything Suddenly Got Worse and What to Do About It

by Cory Doctorow · 6 Oct 2025 · 313pp · 94,415 words

Co-Intelligence: Living and Working With AI

by Ethan Mollick · 2 Apr 2024 · 189pp · 58,076 words