urban renewal

description: program of land redevelopment in cities, often where there is urban decay

332 results

Saving America's Cities: Ed Logue and the Struggle to Renew Urban America in the Suburban Age

by

Lizabeth Cohen

Published 30 Sep 2019

This book will contend that policies and practices of urban renewal evolved and improved over time. Although many serious mistakes were made, important lessons were also learned. And as a result of ever-shifting approaches to urban renewal, many cities were brought back to economic, cultural, and commercial vitality, with increasing amounts of community participation in the process. Urban renewal as experienced in 1972 was far different from that in 1952. The small glimpse given into Logue’s UDC reveals just how experimental these urban renewal strategies often were. Although this book calls for a fresh reexamination of postwar urban renewal, I will in no way claim that it was always admirable in motive and effective in practice.

…

Ed is truculent when he wants to achieve an objective.”98 Howard Moskof (Yale Law ’59) admitted his own susceptibility. He “caught the disease” of urban renewal after a lunch with Grabino and Logue—“two arrogant sons-of-bitches”—and before very long had joined the team, becoming “just like them—everyone became clones of Logue.”99 New Haven urban renewal was not exceptional in its masculine culture. Urban renewal in many cities was associated with a strong male figure, whether Pittsburgh’s David Lawrence, Newark’s Louis Danzig, San Francisco’s Justin Herman, Philadelphia’s Edmund Bacon, or, the most overbearing of them all, New York’s Robert Moses. This male culture of urban renewal contrasted sharply with Progressivism, which took on a strong female character through the imprint of social reformers and so-called urban housekeepers such as Jane Addams, Florence Kelley, and Lillian Wald, to name only the most prominent.100 Whereas the female Progressives lobbied for new protective legislation for workers, particularly women and children, and organized female consumers to boycott goods produced under exploitative conditions, the male urban renewers controlled large amounts of money and used it to rebuild cities on a massive scale.

…

This male culture of urban renewal contrasted sharply with Progressivism, which took on a strong female character through the imprint of social reformers and so-called urban housekeepers such as Jane Addams, Florence Kelley, and Lillian Wald, to name only the most prominent.100 Whereas the female Progressives lobbied for new protective legislation for workers, particularly women and children, and organized female consumers to boycott goods produced under exploitative conditions, the male urban renewers controlled large amounts of money and used it to rebuild cities on a massive scale. Some architectural critics have taken the analysis even further and argued that the aesthetics of urban renewal carried the stamp of this male-dominated culture, with urban renewers like Lee and Logue attracted to a hard-edged, high-rise, brutalist modernist architecture that celebrated Cold War virility.101 Even without taking that leap, it is possible to say that urban renewal was nourished in a male culture of expertise and sociability that encouraged big men to build big structures with big ambitions.

Cape Town After Apartheid: Crime and Governance in the Divided City

by

Tony Roshan Samara

Published 12 Jun 2011

The CFRS was intended to combat crime on the Flats in line with directives laid out in the National Crime Prevention Strategy (NCPS) and to complement the National Urban Renewal Programme (NURP). It was linked, at least conceptually, to the urban renewal process under way in the city center through its incorporation of the spatial governance model of reclaiming and revitalizing key geographic nodes. The CFRS, like the central city’s improvement district model, also foregrounds crime and security, making very clear that its primary task of urban renewal is to address the “gang phenomenon.” The goal here, according to law enforcement and political authorities, is not simply a “cleanup” for which a “broken window” strategy will suffice, though it will have a role to play.

…

In the process, social development, including youth development, while still a goal of urban renewal on the Flats, was neglected in practice. For too many young people in the townships, as the arrest statistics in the preceding chapter indicate, the primary experience they had with the new strategy was through the police. Policing was quickly becoming the central mechanism in the urban renewal program and a primary institution mediating relations between the state and the people, as the police not so quietly slipped into the role of de facto agents of underdevelopment. Understanding how and where young people fit into urban renewal on the Cape Flats—the focus of the next chapter— thus turns on an understanding of how gangsterism and policing have come to largely define the parameters of development practice in this vast territory to the east of the city’s core.

…

In Dixon’s examples of sector policing, it becomes evident that police commitment to communityoriented policing is not at this point secure, and could in fact weaken if police have access to resources to “go straight and . . .” The implications for urban renewal on the Cape Flats is significant, as urban renewal is steadily becoming a process of disciplining youth who have been largely abandoned by other, more supportive state initiatives. The police become in this situation the state workers thrown into this gap between what government cannot provide but the criminal underground can. Arguably, the most troubling indication of the direction urban renewal is headed is the growing of the divide between the stated commitment to social crime prevention in principle and the actual practice.

City: Urbanism and Its End

by

Douglas W. Rae

Published 15 Jan 2003

At the same time, the state of Connecticut had, with some urging from Lee, passed Public Act 24 (1958), Public Act 8 (1958), and Public Act 594 (1961) offering state funding for the local share of specified aspects of urban renewal.19 The net effect of these machinations is that the local percentage of total urban renewal costs was very low indeed. City urban renewal cash spending from locally generated revenues appears to have amounted to as little as 5 percent of total urban renewal costs during the Lee era as a whole. Not only was the funding largely beyond the pockets of New Haven voters, it was largely beyond the control of city government at large.

…

No attempt to hinder school performance, or to encourage unemployment and even criminality, could have been much better designed than the piling up of subsidized low-income housing in exactly the places jobs were (or would become) hardest to find. Third, and most central to the end of urbanism, comes urban renewal as first authorized under Title I of the Housing Act of 1949, and expanded under the Housing Act of 1954. Richard C. Lee, who served as mayor from 1954 –70, quickly became the most visible leader in urban renewal nationally, being credited in one instance with having created in New Haven the nation’s first “slumless city.” New Haven pursued urban renewal more vigorously, more ingeniously, and more expensively (per capita) than any other city in the country.66 One whole neighborhood, doubtless meeting the common man’s definition of a slum, was razed.

…

At first called “urban redevelopment,” the federal program was renamed “urban renewal” in 1954, just as Lee came to power.2 He would respond by hiring a technocratic elite (I will call them the tigers), creating a virtual alternative government for them to operate (I will call it the Kremlin), obtaining a stream of financial resources from outside the city to nurture their programs (the federal aorta, discussed below), and assaulting the problems of the city and its neighborhoods with urban renewal and social renewal programs on a massive scale. Together, these constitute the extraordinary politics of the Lee era and urban renewal. A TIGER IN THE CELLAR Lee set out to recruit the smartest and most arrogant people who had ever served in the management of so modest an American city as New Haven.

The Metropolitan Revolution: The Rise of Post-Urban America

by

Jon C. Teaford

Published 1 Jan 2006

Chester Hartman, “The Housing of Relocated Families,” in Urban Renewal: The Record and the Controversy, ed. James Q. Wilson (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1966), p. 306. 81. Marc Fried, “Grieving for a Lost Home: Psychological Costs of Relocation,” in Urban Renewal, ed. Wilson, p. 360. 82. Wolf Von Eckardt, “Bulldozers and Bureaucrats,” New Republic, 14 September 1963, p. 15. 83. Martin Anderson, The Federal Bulldozer: A Critical Analysis of Urban Renewal, 1949–1962 (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1964), pp. 54–55. 84. Herbert J. Gans, “The Failure of Urban Renewal,” in Urban Renewal, ed. Wilson, p. 541. 85. Gillette, Between Justice and Beauty, p. 165. 86.

…

In a number of cities of the trans-Mississippi West, federally financed urban renewal proved so unacceptable that it never was implemented. Although business leaders in Omaha’s chamber of commerce were eager to apply federal dollars to that city’s graying core, the local electorate and city council were adamantly opposed to the program and repeatedly defeated renewal proposals. Consequently, there were no federal urban renewal projects in the Nebraska metropolis.75 Because of its refusal to adopt zoning ordinances, Houston was automatically ineligible for federal urban renewal money. Moreover, Houston residents did not seem to care; one official observed that “urban renewal was not even in our lexicon.”76 Strong ideological scruples motivated opponents of federal urban renewal in Fort Worth, where the Citizens Committee for Protection of Property Rights led the crusade against government condemnation of blighted properties.

…

Moreover, Houston residents did not seem to care; one official observed that “urban renewal was not even in our lexicon.”76 Strong ideological scruples motivated opponents of federal urban renewal in Fort Worth, where the Citizens Committee for Protection of Property Rights led the crusade against government condemnation of blighted properties. In a 1966 referendum, Fort Worth conservatives decisively consigned urban renewal to oblivion when voters rejected it by a 4 to 1 margin.77 Nearby Dallas was equally offended by the prospect of federal assistance and never signed on to the program. In 1965 Salt Lake City voters rejected federal money by a 6 to 1 margin after a campaign that, according to one urban scholar, “described urban renewal as a violation of the divinely given right of property ownership.”78 In 1964 Denver residents defeated an urban renewal proposal, following the lead of a city council member who deemed public condemnation of land for resale to private interests as “immoral.”79 Two years later, Denver’s electorate changed its mind and approved the scheme.

City for Sale: The Transformation of San Francisco

by

Chester W. Hartman

and

Sarah Carnochan

Published 15 Feb 2002

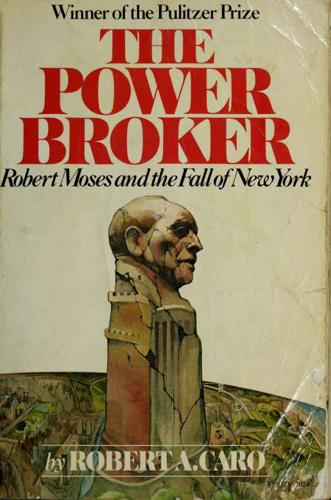

The ratio of annual administrative budget to total grant was 1:77 for Pittsburgh and 1:55 for Boston, while San Francisco had a 1:22 ratio. 7. For portraits of the few figures in the urban renewal game who rivaled Herman, see (on Robert Moses) Jeanne Lowe, Cities in a Race with Time (New York: Random House, 1967), 45 – 109, and Robert Caro, The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1974); (on Edward Logue) Richard Schickel, “New York’s Mr. Urban Renewal,” New York Times Magazine (1 March 1970). See also Jewel Bellush and Murray Hausknecht, eds., “Entrepreneurs and Urban Renewal: The New Men of Power,” in Urban Renewal: People, Politics and Planning (New York: Doubleday Anchor, 1967), 289 – 97.

…

Traditional controls of public power, so endemic in American government, run a little thin with these agencies.1 The SFRA was established in 1948 in anticipation of passage by Congress of the 1949 Housing Act, which introduced the urban renewal program. Like redevelopment bodies in general, SFRA is a semiautonomous entity with vast independent legal, financial, and technical powers and 15 16 / Chapter 2 resources. Its commissioners are appointed by the mayor and confirmed by the Board of Supervisors. During the heyday of urban renewal—the 1960s and first half of the 1970s—the agency had access to massive sums of federal funds; between 1959 and 1971, it was able to secure $128 million in federal urban renewal dollars for the city. Its relative freedom from local control and its direct access to federal money tended to reduce city hall control over its activities.

…

Its large technical staff developed an exclusive familiarity with the complex arcana of federal urban renewal statutes and administrative regulations. It is able to issue its own bonds. It has and extensively uses the power of eminent domain, and even when such power is not directly used, that lurking presence often creates “willing” sellers. During most of its first decade, SFRA’s operations and importance were limited, as evidenced by a small and not very talented staff, generally uninspired appointments to its governing board, and frequent squabbles both internally and with federal urban renewal officials. Urban renewal was new, and direction and support from Washington was less than optimal.

Makeshift Metropolis: Ideas About Cities

by

Witold Rybczynski

Published 9 Nov 2010

Other public and private developments included a maritime museum, berthed historic ships, and an amusement park on a cargo pier, as well as Fisherman’s Wharf itself, once the center of San Francisco’s commercial fishing fleet and now a collection of waterside seafood restaurants. Ghirardelli Square in San Francisco introduced a new urban-renewal formula: rehabilitated waterfront buildings + commerce + tourism = downtown activity. Fisherman’s Wharf is an example of successful revitalization based not on urban renewal, public housing, or grand civic projects, but on tourism. Tourism was largely ignored by the first generation of urban-renewal planners—even Jane Jacobs had nothing to say about it—but it proved to be a powerful economic force for urban change. Cities that couldn’t recover lost manufacturing and industrial jobs discovered something that older European cities such as Venice and Vienna had known for a long time: instead of offering financial services or manufacturing shoes, a city could sell pleasure.

…

The challenge for planners is how to jump-start development without falling into the pitfalls that plagued the large urban-renewal projects of the 1950s. This can be difficult, as the checkered history of Penn’s Landing in Philadelphia demonstrates. The seventy-five-acre site on the Delaware River was created in the early 1960s with landfill from the construction of a sunken crosstown expressway. Penn’s Landing, at the foot of Market Street and adjacent to downtown, was seen as a potentially lucrative development opportunity by the city, which owned the site, and the city department of commerce commissioned a master plan for the area. In the prevailing spirit of urban renewal, the development was conceived as a superblock, consisting of a landmark office tower housing the port authority, additional office space, a science park, and a boat basin.

…

This explains the willingness to attempt radical and untested urban interventions such as urban renewal, traffic separation, high-rise social housing in the cities, and dispersed planned communities in the suburbs. The current stalled economy has produced a call for massive government spending in the public sector. Inevitably, much of this spending will take place in cities and metropolitan areas. Architects and planners will once again be tempted to implement grand urban visions—twenty-first-century versions of urban renewal and the Radiant City. The temptation will be particularly great since government-funded projects provide freedom from the constraints imposed by the market, an opportunity to replace demand-side urbanism with supply-side planning; us telling them what they should like, just as in the good old days.

Hollow City

by

Rebecca Solnit

and

Susan Schwartzenberg

Published 1 Jan 2001

"^ a mall-like version of Japantown was Iron- rebuilt, backed by investors from Japan and opposed by THE SHOPPING CART AND THE LEXUS many Japanese-American community (which had dispersed in the local after returning ft-om the where internment camps following World Western Addition, bauhaus bunkers were the Afi-ican Americans displaced by urban renewal, but a signifi- move back and the second phase of urban renewal displaced another 13,500 dents of the Western Addition. Chester Hartman, who at resi- has written exten- about urban renewal in San Francisco, concludes that the Redevel- sively opment Agency "became much downtown as Else- house cant portion of the 4,000 families evicted were unable to all, War II). built to in the some of 49 a powerful land as and aggressive army out to capture The Agency turned could it sweeping out the poor, with the atically full backing of the to system- power city's elite.">° In the some Western Addition, urban renewal met with In make them more mixed response: some opposed them, and many believed the promises, sought to a palatable or to advance their own leaders agendas.

…

"^ The housing conditions were sometimes vile, but they were the result rather than the cause of social problems (the poet Michael McClure, who visited many of the homes while working 1960, for the census in remembers them cious).'* as airy and gra- Nevertheless, urban renewal went forward, propelled by the peculiar official belief that problems caused by poverty and racism could be cured by architecture often architecture that removed population is now make would exclude (just as the homelessness often addressed by attempting to away the homeless go —not into houses, just out of sight or out of town). By the time urban renewal in the Victorian houses that Western Addition had begun its second where the campaign, the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency could write, "San Francisco is now developing programs to correct blighted and congested were removed to be Fillmore Center — so they were retically, everyone in who was uously aging and deteriorating faster than replaced.

…

disbanded a year or so ago, several other organiza- sprung up to deal with the burgeoning eviction and homeless- ness problems. And the new battlefront is the Mission. The Mission, which survived urban renewal untouched, force entirely. Gentrification vate, individual acts Ruth ing-class quarters upper and lower a facing another cumulative public effect of numerous and thereby action of urban renewal. ish sociologist is is far harder to resist than the institutional The word itself was first used in 1964 by the Glass, who pri- wrote, "One by one, many Brit- of the work- of London have been invaded by the middle classes Once this process of 'gentrification' starts in a district.

Mysteries of the Mall: And Other Essays

by

Witold Rybczynski

Published 7 Sep 2015

Airports couldn’t be built downtown, of course, but parts of downtown could be brought to the airport. * * * In 1967, Pritzker bought an unfinished hotel in central Atlanta and built a giant atrium hotel, initiating an architectural trend that has lasted until the present day. Over the last two decades, his downtown hotels have been a part of urban renewal in Chicago, San Francisco, Dallas, Pittsburgh, Minneapolis, Miami, and Memphis. Stanley Durwood’s company, too, returned to the city. The multiplex was born in the suburbs, and the sprawling one-story buildings were built in suburban malls, often near one of Frank Turner’s highway interchanges.

…

Downtown “The almighty downtown of the past is gone—and gone for good,” writes Robert Fogelson in Downtown, his stimulating new history of a long-neglected subject. “And it has been gone much longer than most Americans realize,” he continues. The provocative second part of this statement encapsulates his thesis: that long before the failures of urban renewal, the intrusions of urban interstate highways, and the competition of suburban shopping malls and office parks, the primacy of downtown was on the wane. Most recent books that deal with downtowns have done so in the context of urban advocacy, describing them as a precious part of our heritage that needs to be saved, revitalized, restored.

…

Fogelson describes various attempts in the 1930s and 1940s to stem the tide and attract citizens back to downtown. These included not only expanded mass transit but also road improvements and solutions to automobile parking. Immediately after World War II, there was also slum clearance—the antecedent to the urban renewal projects of the 1960s. If the blighted areas adjacent to downtown could be improved, the reasoning went, the middle class would return, and downtown would thrive once more. By then, it was too late. The chief reason that Americans stopped going downtown, according to Fogelson, is that they no longer wanted—or needed—to.

Stuck: How the Privileged and the Propertied Broke the Engine of American Opportunity

by

Yoni Appelbaum

Published 17 Feb 2025

Returning home to Hudson Street, Jacobs pounded out The Death and Life of Great American Cities on her Remington. Her book, published in 1961, took aim at urban renewal and painted a vivid picture of all that it destroyed in the name of progress. When, that same year, Jacobs learned that the city intended to designate her own neighborhood for renewal, she rallied the inhabitants to its defense. And it worked. Jacobs and her collaborators were the first residents of a city neighborhood to successfully block an urban renewal scheme. Jacobs’s book—its brilliantly observed account of urban life, its adages and conjectures—paired with her success as an activist to catapult her to fame.

…

Flint’s more affluent neighborhoods and the suburbs that surrounded the city generally barred multifamily construction and demanded large lot sizes that produced lower densities and higher prices. So even where overt racial discrimination faded, economic segregation tended to produce the same result. Flint’s urban renewal program in the 1950s both highlighted and exacerbated these inequalities. When federal funds first became available, Flint’s Black communal organizations clamored for inclusion in urban renewal, hoping to sweep away dilapidated housing from their neighborhoods and replace it with adequate dwellings. Flint’s planners were equally eager to demolish Black neighborhoods, but notably less committed to helping their residents move up.

…

GO TO NOTE REFERENCE IN TEXT Progress toward formal legal equality: Martha Biondi, To Stand and Fight: The Struggle for Civil Rights in Postwar New York City (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2006), 286–87. GO TO NOTE REFERENCE IN TEXT In 1968, after a long: Highsmith, Demolition Means Progress, 164–74. GO TO NOTE REFERENCE IN TEXT Flint’s urban renewal program: “Urban Renewal Development Plan, St. John Street Renewal Area” (Department of Community Development, n.d.), 19, box 1, folder 24, Flint Department of Community Development Collection, Genesee Historical Collections Center. GO TO NOTE REFERENCE IN TEXT Flint would manage to annex: Highsmith, Demolition Means Progress, 114–44; William Orville Winter, “Annexation as a Solution to the Fringe Problem: An Analysis of Past and Potential Annexations of Suburban Areas to the City of Flint, Michigan” (PhD diss., University of Michigan, 1949), 12–14.

Naked City: The Death and Life of Authentic Urban Places

by

Sharon Zukin

Published 1 Dec 2009

In Boston the sociologist and urban planning researcher Herbert Gans wrote a stunning indictment of how local elites needlessly destroyed the Italian working-class district of the West End, coining the term “urban village” to depict the close-knit, family-based, ethnic community that was displaced in the name of slum clearance. Even more famously, in New York the journalist and community activist Jane Jacobs published a call to arms against the fatal machinery of modern urban planning, which brought in the bulldozers and “cataclysmic money” of urban renewal projects to destroy old, but still vibrant, neighborhoods. By the early 1960s, with urban renewal moving forcefully ahead, its opponents developed a modest, street-level defense of urban authenticity to confront the arrogance of both modernization and state power, which threatened to sweep away people as well as buildings.12 The men and women who spoke up for authenticity in the 1960s were a mixed group socially, culturally, and politically, and they argued for somewhat different visions of the city.

…

Title I of the federal Housing Act passed by Congress in 1949 included a provision for funding these projects, as well as the expansion of urban universities, and it enabled developers and public sector entrepreneurs to make the city grow as they desired.11 This vision of the city provoked opposition and even outrage. Henry James’s critical themes reemerged, but from a far more populist point of view. He had never liked the immigrants, namely Jews, who in his time thronged the streets of the tenement districts of the Lower East Side. Critics of urban renewal, though, added what we would now call positive goals of affordability and diversity to James’s hostility to overbuilding. In Boston the sociologist and urban planning researcher Herbert Gans wrote a stunning indictment of how local elites needlessly destroyed the Italian working-class district of the West End, coining the term “urban village” to depict the close-knit, family-based, ethnic community that was displaced in the name of slum clearance.

…

The much-quoted set piece in the first section of Jacobs’s best-selling 1961 book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities—an hour-by-hour description of the “intricate sidewalk ballet” on Hudson Street, outside her window—dramatizes the neighborly interdependence of local shopkeepers, housewives, schoolchildren, and customers at the corner bar, all patron saints of social order in the city’s neighborhoods who were either scorned or ignored by the powerful forces that controlled urban renewal. Jacobs also argued for authenticity as a democratic expression of origins, for a neighborhood’s right, against the decisions of the state, to determine the conditions of its own survival. Death and Life raised an alarm against the arrogance of state power, especially as it was personified by Robert Moses, the larger-than-life administrator who headed the most important state and city redevelopment agencies in New York City from the 1930s to the 1960s.

How to Kill a City: The Real Story of Gentrification

by

Peter Moskowitz

Published 7 Mar 2017

Black people in Detroit and all across the country not only were pushed into city centers and held there by racist suburban policy but were repeatedly internally displaced by the forces of “urban renewal.” Federally funded highways began cutting through Detroit after World War II. The highways weren’t just ways to subsidize white flight to the suburbs; local politicians considered them a “handy device for razing the slums.” Detroit displaced nearly 2,000 black families from one area along Gratiot Avenue in 1947 for the sole purpose of getting rid of a section of the city that used more tax dollars than it gave back. Mayor Albert Cobo called urban renewal the “price of progress.” The effect of decades of segregation is that black Americans are poorer and less likely to achieve success than whites.

…

The site is rarely criticized today because the buildings occupy hallowed ground, but before September 11 the Twin Towers were considered examples of terrible urban planning. And they were one of New York’s biggest “urban renewal” projects: to make way for the massive structures, some 33,000 workers and small-business owners were displaced. Planners and politicians often like to pretend we’ve moved past the urban renewal era—when highways and super-tall buildings were rammed through neighborhoods (most often majority-black ones, though in the case of the original World Trade Center many of the displaced were Syrian) in the belief that whatever came next would be more profitable and less social-service-intensive than what was there before.

…

In a society in which land can be bought and sold, every place has both a use value and an exchange value. The inherent problem with this setup is that the poorer you are, the more likely it is that places that provide you with use value don’t offer an increased exchange value for anyone else. Molotch and Logan point out that in the heyday of urban renewal—when highways and housing projects were forced on top of low-income neighborhoods, displacing tens of thousands—the main metric for deciding where these projects should go was not crime, education, or the health of its residents, but whether those areas could be used for more profitable things.

Creating Unequal Futures?: Rethinking Poverty, Inequality and Disadvantage

by

Ruth Fincher

and

Peter Saunders

Published 1 Jul 2001

Manifestations of disadvantage, however, distinguish these two localities, as discussed below. Because the areas are delimited sections of larger ABS spatial aggregates (such as postcodes or statistical local areas), the presence and level of disadvantage can only be gleaned through local knowledge and on-site visits. Public housing and urban renewal The planned urban renewal of Manoora surfaced in each interview as a major initiative to tackle the spatial expression of conspicuous inequalities in Cairns. During the discussions, however, it became clear that Manoora was grouped in people’s perceptions with Mooroobool and Manunda, two other areas of public housing concentration located in the same central Cairns postcode zone.

…

This appears to be a product of the city’s topography—leafy hillside suburbs edge the lower income plains suburbs in many spots and new semi-gated communities of high-cost housing sit up the hill from areas of cheaper homes. Urban renewal refers to the current strategy of Australian State housing authorities that aims to address the concentration of disadvantage on public housing estates. Urban renewal initiatives can take a number of forms including upgrading ageing public dwellings, demolishing stock, selling off some public housing and/or relocating tenants. But overall, this policy has been ‘little 174 PDF OUTPUT c: ALLEN & UNWIN r: DP2\BP4401W\MAIN p: (02) 6232 5991 f: (02) 6232 4995 36 DAGLISH STREET CURTIN ACT 2605 174 MOVING IN AND OUT OF DISADVANTAGE debated or systematically analysed’ (Arthurson 1998, p. 35), although the policy impetus clearly derives from concern over the lack of social mix in public housing estates.

…

Relocating residents, one community worker said, ‘provides people with a new start’. Another social service professional echoed this sentiment and said ‘urban renewal will make a difference to the quality of lives’. Other arguments in favour involved the belief that the standard of housing may be improved if a proportion transfers into private ownership; that children living in the area will be surrounded by a broader selection of role models; and that, essentially, relocating low-income households will break up any ‘culture of poverty’ that may develop. Despite the general support for urban renewal, whereby population mobility, via relocation of low-income tenants, becomes a poverty reducing mechanism, it remains a very complex social policy issue.

The Making of a World City: London 1991 to 2021

by

Greg Clark

Published 31 Dec 2014

While many aspects of the impetus towards self-government remain more aspirational than real, one area where integrated organisation and resources has been achieved is in city promotion, which is featured in the concluding section of the chapter. Acquisition of new global roles, and expansion of existing proficiencies, has required that London’s policy makers undertake numerous projects of urban renewal and regeneration since 1991. The story of redevelopment and re-use of brownfield land, waterfronts, markets, stations, stadia and high streets is told in Chapter 6. After the mixed experience of the London Docklands Development Corporation in the 1980s, the 1990s constituted a noticeable shift towards the deployment of public sector physical infrastructure investments to catalyse wider private sector activity.

…

Later, under New Labour, the New Deal for Communities initiative sought a more proactive rehabilitation of dysfunctional social housing estates. The dual focus on connectivity infrastructure and property-led regeneration as a form of social engineering – such as occurred in Hackney’s Holly Street Estate – was indicative of the dominant role that bricks and mortar played in the architecture of urban renewal at this time. With this in mind, the assessment of Simon Clark, Partner and Head of European Real Estate at Linklaters, is that “in the 1990s London became much more conscientiously involved in its own reinvention. Major urban development projects and major infrastructure initiatives, as well as key celebrations, enabled London to believe it was possible to physically change the city to create new capacity and new quarters and new local identities” (personal communication, 6 December 2011).

…

Conversely, the fact that Canary Wharf had had patchy impact on the adjacent areas of East London, with benefits mostly confined to the former Docklands area from Limehouse to Royal Victoria Dock, meant that the Olympics came to be seen as a viable opportunity to undertake more comprehensive social regeneration in East London. Late 1990s regeneration: Marrying infrastructure and pluralism The ascent of New Labour’s Model of post-industrial services and consumer-led economy in the late 1990s had a considerable impact upon the trajectory of urban renewal. At this point, policymakers for London embraced the already circulating idea that an image of liveability must be central to the capital’s competitive capability in a global knowledge economy where diversity and inclusivity had become paramount. London’s global city roles required not only a suitable range of high-end housing and corporate real estate, but an accompanying cultural, leisure and retail offer.

Vanishing New York

by

Jeremiah Moss

Published 19 May 2017

When public health psychiatrist Mindy Thompson Fullilove talks about root shock, she describes a complex traumatic stress reaction to urban renewal. The displacement of a physical and emotional ecosystem, she writes, “destabilizes relationships, destroys social, emotional, and financial resources, and increases the risk for every stress-related disease.” Robert Moses’s meat axe had torn apart the urban ecosystems that provided stabilizing social structures for people who could not flee to the suburbs. Fullilove concludes that urban renewal disabled black communities and led to “great epidemics of drug addiction, the collapse of the black family, and the rise in incarceration of black men,” the very catastrophes that emerged in 1960s New York and contributed to backlash.

…

Fullilove concludes that urban renewal disabled black communities and led to “great epidemics of drug addiction, the collapse of the black family, and the rise in incarceration of black men,” the very catastrophes that emerged in 1960s New York and contributed to backlash. Those angry, frightened ethnic whites, while they had more options than people of color, were also traumatized by urban renewal. They lost their ecosystems, too. Their roots were also shocked. When they “exchanged wonderful urban neighborhoods for cars, malls, and lawns” in the alienated suburbs, writes Fullilove, “they abandoned not just the city but also the togetherness and sociability of their heritage.” The emotional fallout of urban renewal was rage, for black and white, a painful loss still not grieved. Reporting on white working-class New York’s rage and loss in 1969, Pete Hamill wrote, “It is very difficult to explain to these people that more than 600,000 of those on welfare are women and children; that one reason the black family is in trouble is because outfits like the Iron Workers Union have practically excluded blacks through most of their history; that a hell of a lot more of their tax dollars go to Vietnam or the planning for future wars than to Harlem or Bed-Stuy; that the effort of the past four or five years was an effort forced by bloody events, and that they are paying taxes to relieve some forms of poverty because of more than 100 years of neglect on top of 300 years of slavery.

…

Thankfully, the fifth generation of Moscots will continue examining eyes and fitting frames at the Lower East Side crossroads. For now, anyway. Delancey is undergoing a total evisceration. In the fall of 2013, a few months before his tenure ended, Mayor Bloomberg and a group of developers announced the grand plan for “Essex Crossing,” a reconstruction of the Seward Park Urban Renewal Area (SPURA), a site that had long endured a controversial history. In 1967, the city demolished fourteen blocks of tenements here, evicting more than two thousand working-class and poor residents, Latino, white, black, and Chinese, to make room for market-rate housing and a section of Robert Moses’s Lower Manhattan Expressway.

The Great Good Place: Cafes, Coffee Shops, Bookstores, Bars, Hair Salons, and Other Hangouts at the Heart of a Community

by

Ray Oldenburg

Published 17 Aug 1999

Usually, this is carried off right in the downtown or “showplace” areas of the city. Whatever profit realized at such shops is often incidental to the real “kill” the owner may anticipate when the area comes under an urban renewal program, at which time the lots on which such buildings are located command a premium price. The existence of the porno shops, of course, adds considerable impetus to the demand for urban renewal. Things work out rather nicely for entrepreneurs who understand the failings of our system and who have no qualms about taking advantage of them. They and their right to debase communities even as they profit from doing so are guaranteed by the Constitution, but their real benefactor is that Anglo-Saxon tradition alluded to by Jane Addams.

…

For all the consternation she caused within architectural and planning circles, she has done a tremendous service for us all. One marvels at both the depth and quantity of her insights. Well within the Jacobs’ tradition and appearing the same year as my contribution was Roberta Gratz’s The Living City. Gratz’s book contrasts grass roots successes at rebuilding neighborhoods with the disasters wrought by “urban renewal.” Victor Gruen’s The Heart of Our Cities is still a book worth not only owning but using as a reference work for all aspects of urban and neighborhood development. Gruen is the man who conceived and planned our nation’s first covered shopping mall. He came to reject the designation, “father of malling” because his plan was stripped down to commercialism only.

…

The flash crowd was fickle, of course, and when it moved on to other “discoveries,” all that remained was the wreckage of what had once been good bars. In the United States, the college crowd has similarly ruined many a good place and threatened a great many more. McSorley’s Old Ale House in New York City, perhaps the oldest bar in America, has survived urban renewal and the blood lust of feminists seeking to integrate or destroy it. But it faces its greatest threat in the form of college students who make meals of its cheese platters and take over the place at night.14 Those invaders contribute nothing to the charm or the amenities that have attracted them; once those features are ruined, they move on to other victims.

Paved Paradise: How Parking Explains the World

by

Henry Grabar

Published 8 May 2023

” * * * Not every city had a Gruen project, but all of them tried their hardest to get the downtown core parked to suburban standards. They accomplished this in three ways. First, American city leaders jumped to support highway and Gruen-style urban renewal projects that demolished older neighborhoods. With either intervention, local planners were given great power to rebuild cities according to two tenets of midcentury urbanism: separate residential neighborhoods from commerce and industry and accommodate drivers lest they take their business to the suburbs. Urban renewal projects targeted dilapidated but lively residential and commercial blocks for demolition. In their stead came car-oriented malls, office towers, and apartments.

…

And even Jane Jacobs, germinating the ideas that would make up her landmark antiplanning book The Death and Life of Great American Cities, wrote a self-described “fan letter” to Gruen, saying his Fort Worth plan was of “incalculable value” and would return America to a time of “downtowns for the people.” But Gruen never got his Fort Worth plan: the Texas legislature was not so easily charmed by the vision of the Viennese architect who flew in from Los Angeles, and rejected Gruen’s allies’ urban renewal bill. Then, in a death blow, the legislature barred Texas cities from building municipal parking garages. In a 1980 appraisal, The Washington Post blamed private parking lot operators for spoiling the dream. But the Fort Worth plan, the newspaper concluded, “is the only unborn child who had hundreds of grandchildren.”

…

In their stead came car-oriented malls, office towers, and apartments. Some projects succeeded, some failed. All aimed to satisfy the expectation of easy driving and parking at the center of the city. What really stood out about urban renewal, to contemporaries, was its extended time span: the average project lasted twelve years from the moment official planning began (all but ensuring no further neighborhood upkeep would occur) to completion. That lost decade worked to drivers’ advantage: cleared land could provide much-needed parking lots. In Buffalo, a chamber of commerce staff member observed that so many buildings had been demolished it looked like the city was paving the way not for cars to park but for airplanes to land.

Radical Cities: Across Latin America in Search of a New Architecture

by

Justin McGuirk

Published 15 Feb 2014

But the bigger problem seems to be that in such cases the demolition team has to collaborate with social workers – a sensible policy, only in this case the social workers’ contract has expired and the demolition cannot continue without them. Such are the mundane causes of the tragic scenes around us – all of this because of bureaucratic incompetence. It is a stark reminder that you can design all the masterplans you like, but if the administrative process that’s supposed to deliver an urban renewal project doesn’t function, then lives get ruined. In Brazil, the bureaucratic machinery needs redesigning as much as the urban fabric. One of the houses standing alone in the rubble has a smartly tiled facade and a hanging chair out on the balcony. My guide says it’s the most beautiful house in the area, and the owner was offered an unprecedented 138,000 reais ($63,000) in compensation.

…

‘They’re just relocating poverty,’ my guide says. An Olympic Legacy? In 2010, Mayor Eduardo Paes announced that all of Rio’s favelas would be upgraded by 2020. It was a bold statement, and one that the Brazilian architecture community met with optimism rather than disbelief. The mayor’s primary tool in this sweeping transformation was an urban renewal programme called Morar Carioca – Carioca Living. With 8 billion reais of funding, it was the most ambitious slum regeneration project ever launched, dwarfing Favela-Bairro. In the same vein as its predecessor, Morar Carioca was to continue the process of stitching the favelas into the urban fabric of Rio.

…

Dramatic falls in homicide rates, traffic congestion, traffic accidents and water usage, and a burgeoning civic pride. However, his impact on Bogotá, though powerful, was an intangible one. That is not quite true – in one sense it was highly material. Mockus restored the city’s finances. He inherited a city with a deficit and left it with a healthy budget for urban renewal projects. He did this partly by raising taxes. Much as he had done at the university, he persuaded 55,000 of Bogotá’s wealthiest residents to pay an extra 10 per cent in tax. He also sold off part of the municipal telecommunications company (and when he was accused of neoliberalism for selling off a public asset, he was able to counter that not many neoliberals are in favour of raising taxes).

Data Action: Using Data for Public Good

by

Sarah Williams

Published 14 Sep 2020

These maps have become important symbols for how visualizations can be used powerfully, often by the powerful, to oppress the powerless. These maps permanently marked these urban landscapes as “other,” places not worth investing in, and the ramifications of that labeling can still be seen today. Data and Urban Renewal Technocratic planners continued to apply data and mapping to urban renewal policies in the 1950s, securing funds from federal highway and housing grants (the 1949 Housing Act, for example) that could be gotten only if data were submitted as evidence in the application for funding. In cities across the country, technocratic planners devised ways to send highways through thriving neighborhoods they designated as “blighted” in the hopes of permanently removing these areas, using data as evidence.

…

By allowing land use that was not permitted in other residential neighborhoods—polluting industries, taverns, liquor stores, nightclubs, and brothels—the segregation helped turn these African American neighborhoods into slums.59 African American homes in these neighborhoods were not eligible for Federal Housing Commission mortgages because their terms did not provide for incongruent use. Ironically, these zoning and use designations helped St. Louis garner urban renewal funds that paid for the ultimate clearing of many of these communities, which in one case led to the design and construction of the infamously dysfunctional Pruitt-Igoe housing project.60 Some might argue that the clearing of these communities was always the goal of St. Louis's exclusionary zoning practices.

…

Planning historians believe that the destruction of the neighborhood (figure 1.26) aligned with Miami businessmen's racial goals for their city, and according to several accounts, with their conviction that the African American presence would stifle the city's development.67 This pattern of racist reasoning became standard practice during urban renewal and led to the destruction or marginalization of many more African American neighborhoods across the country, with data used as evidence to garner the necessary funds to make it possible. 1.25 This street scene of Overtown shows African American shoppers outside the retail establishments along NW 2nd Avenue between 8th and 9th Streets, circa 1950.

Triumph of the City: How Our Greatest Invention Makes Us Richer, Smarter, Greener, Healthier, and Happier

by

Edward L. Glaeser

Published 1 Jan 2011

He ended up preferring pay raises to strikes, and the increasing costs of city government were then hidden with increasingly creative bookkeeping, which led straight to New York’s near bankruptcy in 1975. Cavanagh’s fatal flaw was his penchant for razing slums and building tall structures with the help of federal urban-renewal dollars. Detroit’s housing market had peaked in the 1950s and was already depressed when Cavanagh took office. The city was shedding people and had plenty of houses. Why subsidize more building? Successful cities must build in order to accommodate the rising demand for space, but that doesn’t mean that building creates success. Urban renewal, in both Detroit and New York, may have replaced unattractive slums with shiny new buildings, but it did little to address urban decline.

…

Shiny new real estate may dress up a declining city, but it doesn’t solve its underlying problems. The hallmark of declining cities is that they have too much housing and infrastructure relative to the strength of their economies. With all that supply of structure and so little demand, it makes no sense to use public money to build more supply. The folly of building-centric urban renewal reminds us that cities aren’t structures; cities are people. After Hurricane Katrina, the building boosters wanted to spend hundreds of billions rebuilding New Orleans, but if $200 billion had been given to the people who lived there, each of them would have gotten $400,000 to pay for moving or education or better housing somewhere else.

…

Riding on the People Mover feels like a trip to Disney World, if Disney World were in the middle of a desperate city. But as in other declining places, billions were spent on infrastructure that the city didn’t need. Unsurprisingly, providing more real estate in a place that was already full of unused real estate was no help at all. The failures of urban renewal reflect a failure at all levels of government to realize that people, not structures, really determine a city’s success. Could an alternative public policy have saved Detroit? By the time Young was elected, Detroit was far gone, and I suspect that even the best policies could only have eased the city’s suffering.

Why Nothing Works: Who Killed Progress--And How to Bring It Back

by

Marc J Dunkelman

Published 17 Feb 2025

Having abandoned the First New Deal’s associationalism for the Second New Deal’s centralized regulation, progressives now steered more directly into the increasingly influential doctrine of Keynesianism. Rather than manipulating companies and unions like marionettes, or bringing them to heel through administrative fiat, Washington began trying to affect the economy more exclusively through the public purse. Public works projects, guaranteed incomes for farmers, urban “renewal,” public housing, the GI Bill—this broad portfolio of new federal investments was designed to promote, at the national level, what became the postwar promise of progressive politics, namely, “full employment.” Southern Democrats in particular had begun to look with increasing skepticism at the burgeoning desire among northern liberals to interfere with the Jim Crow system of white supremacy—they wanted their region to be left alone.

…

Rockefeller’s proposed salve centered on creating a centralized bureaucracy, a national Urban Development Corporation (UDC), to correct for the scars Moses had left during his long tenure as New York’s most powerful man. Following the Second World War, Congress had appropriated vast sums for “urban renewal,” a program designed to fund state and local efforts to demolish run-down neighborhoods and erect modern new buildings with a bounty of additional housing in their stead. But “slum clearance,” as the policy was more popularly known, had been particularly devastating in New York. Having wrested control of the program, Moses used it in many cases not to target slumlord buildings, but rather to clear whole blocks for redevelopment.

…

Adam Walinsky, one of Robert Kennedy’s former speechwriters and the Democratic nominee for state attorney general in 1970, objected to the sequencing, arguing that the deluge of poorer residents would scare off any prospective middle-class tenants. But Logue, betraying a tendency to treat his detractors much as Moses had when wielding much the same power, turned a deaf ear. “Fuck it,” he told one aide. “I’m going to do that anyway.”10 And the UDC’s ambitions weren’t limited to Rockefeller’s desire to correct for urban renewal. In his pursuit of social justice, Logue began pushing the state’s wealthier, whiter residents—many of whom had fled New York City during the postwar years for the leafy suburbs—to permit new suburban housing for outsiders. After warning the governor that “shit might hit the fan,” he unveiled what he termed a Fair Share Housing plan to build nine hundred affordable units spread between nine of suburban Westchester County’s most well-to-do communities.11 Predictably, local residents were enraged—flabbergasted that a Republican governor they had supported was now proposing to pierce their suburban bubbles.

Planet of Slums

by

Mike Davis

Published 1 Mar 2006

Architect David Glasser visited a former single-family villa in Quito, for example, that housed 25 families and 128 people but had no functioning municipal services.40 Although rapidly being gentrified or torn down, some of Mexico City's vedndades are still as crowded as Casa Grande, the famous tenement block housing 700 people which anthropologist Oscar Lewis made famous in The Children of Sanche% (1961).41 In Asia the equivalents are the decayed (and now municipalized) ^amindar mansions of Kolkata and the poetically named "slum gardens" of Colombo which constitute 18 percent of the city's rundown housing.42 The largest-scale instance, although now reduced in size and population by urban renewal, is probably Beijing's inner slum, the Old City, which consists of Ming and Qing courtyard housing lacking modern facilities.43 Often, as in Sao Paulo's once-fashionable Campos Eliseos or parts of Lima's colonial cityscape, whole bourgeois neighborhoods have devolved into slums. In Algiers's famous seaside district of Bab-elOued, on the other hand, the indigenous poor have replaced the colon working class.

…

After a final defiance — the bulldozing of Colonia Santa Ursula in Ajusco in 29 Young and Turner, The Rise and Decline of the Zairian State, p. 98; Deborah Posel, "Curbing African Urbanization in the 1950s and 1960s," in Mark Swilling, Richard Humphries, and Khehla Shubane (eds), Apartheid City in Transition, Cape Town 1991, pp. 29-30. 30 Carole Rakodi, "Global Forces, Urban Change, and Urban Management in Africa," in Rakodi, The Urban Challenge in Africa, pp. 32-39. 31 Urban Planning Studio, Columbia University, Disaster-Resistant Caracas, New York 2001, p. 25. September 1966 - he was deposed by President Gustavo Diaz Ordaz, a politician notorious f or his many ties to foreign capital and land speculators. A fast-growth agenda that included tolerance for pirate urbanization on the periphery in return for urban renewal in the center became the PRI policy in La Capital.32 A generation after the removal of barriers to influx and informal urbanization elsewhere, China began to relax its controls on urban growth in the early 1980s. With a huge reservoir of redundant peasant labor (including more than half of the labor force of Sichuan, according to the People's Daily) the loosening of the bureaucratic dike produced a literal "peasant flood."33 Officially sanctioned migration was overshadowed by a huge stream of unauthorized immigrants or "floaters."

…

Two residents were shot dead; the rest were trucked out to the countryside, 40 kilometers from their old homes, and left to fend for themselves.28 The most extraordinary contradictions between residual ideology and current practice, however, are enacted in China, where the still putatively "socialist" state allows urban growth machines to displace millions of history's former heroes. In a thought-provoking article comparing recent inner-city redevelopment in the PRC to urban renewal in the United States in the late 1950s and early 1960s, Yan Zhang and Ke Fang claim that Shanghai forced the relocation of more than 1.5 million citizens between 1991 and 1997 to make way for skyscrapers, luxury apartments, malls, and new infrastructure; in the same period nearly 1 million residents of Beijing's old city were pushed into the outskirts 29 In the beginning, urban redevelopment in Deng Xiaoping's China, as in Harry Truman's America, consisted of pilot housing projects that seemed to pose little threat to the traditional urban fabric.

Key to the City: How Zoning Shapes Our World

by

Sara C. Bronin

Published 30 Sep 2024

When we rounded the building to view its eastern façade, we were surprised to find ourselves at the mouth of an outdoor pedestrian mall with about a hundred restaurants and retail stores. Conceived as one of the many federally funded “urban renewal” projects that used federal funding to carry out a big idea in the 1960s and 1970s, the Church Street Marketplace extends four blocks northward, allowing east–west vehicle traffic to intersect it. Although urban renewal has become something of a taboo, associated with dysfunctional public-housing developments and massive highways that obliterated neighborhoods, the Marketplace has endured as a rare success story.

…

Encouraged by rents lower than those in the newer streetcar suburbs, and by the presence of quaint urban dwellings full of character, up-and-coming families invested in restoring the physical integrity of the historic properties. These residents took notice of local preservation ordinances that were adopted in several other cities, and they petitioned the city to follow suit. In 1950 Georgetown was deemed the city’s first historic district, protecting it from further development, including urban renewal. An overhaul of the zoning code in 1958 kept the zoning designations more or less the same. Significantly, despite the collapse of industry in Georgetown, that version of the code preserved the waterfront blocks in industrial districts, which meant residents continued to be cut off from the Potomac as a potential recreational amenity—perhaps no loss given that the river was so polluted at the time.

…

Department of the Interior Office of Archeology and Historic Preservation, Georgetown Historic Waterfront (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1968). 168 became part of the District of Columbia: DC Organic Act of 1871, conclusion 16 Stat. 419. 168 By 1900, 4,000 of Georgetown’s 15,000 residents: Eileen Zeitz, Private Urban Renewal: A Different Residential Trend (Lexington, MA: Lexington Books, 1979), 34. 169 was assigned to the residential district: All the historic zoning maps that I discuss in this chapter are available on the Washington, DC, Office of Zoning website. 169 up-and-coming families invested: Historian Constance Green described the change: “Tiny fenced-off patches of ground at the rear, recently littered with rubbish, again turned into gardens and patios with lilac bushes and crepe myrtle nursed back to vigor by pruning and feeding.

World Cities and Nation States

by

Greg Clark

and

Tim Moonen

Published 19 Dec 2016

Governments have invested large sums to improve Charles de Gaulle Airport and its connections to La Défense and Paris Orsay. The Government also backed Paris 59 bids to host the Olympics, up until 2005 when it surprisingly lost the bid to London for the 2012 Games. Its global perspective was, to some extent, balanced by a commitment to affordability: a ‘Law for Solidarity and Urban Renewal’ makes it compulsory for communes to have 20–25% of social housing in the housing stock by 2020, while the State now offers public subsidies to lower the price of land for housing delivery. In 2008 an important shift occurred when central government appointed a Minister for Le Grand Paris to help a larger Paris “be a decisive national asset in the competition of the twenty‐first century”, according to the official mandate (Lefevre, 2012).

…

The French Prime Minister has expressed determination to meet the ambitious target of 70,000 units a year, a figure far in excess of those proposed in London and New York. The Mobilisation Plan for Development and Housing intends to support communities that innovate to raise the housing rate. The State is also running a New Programme for Urban Renewal at the national level, which has already identified or provided support to 119 housing development and urban upgrade projects in the Paris Region. In addition to co‐financing, it helps mobilise local actors around social and development objectives. It forms part of a broader co‐operation mechanism entitled ‘State‐Region Contracts’, which set out a joint budgetary and planning vision between regions and central government.

…

Such co‐ordination means that when, for example, national government land and buildings are vacated or de‐centralised from Tokyo, they are passed on to the TMG, which actively redevelops in favour of a more attractive mixed‐use model (Fujita and Child Hill, 2005; Pham, 2015). The national Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism (MLIT) retains prerogatives over local urban planning, especially over urban renewal regulations and railway networks. It also oversees the Urban Renaissance Agency – a quango that manages real estate and urban development projects, and has major stakes in Tokyo regeneration schemes, such as the Otemachi district, Minato Mirai 21 and Yokohama (Pham, 2015). The PM’s Office is influential in setting the investment and business promotion agenda for Tokyo.

The Origins of the Urban Crisis

by

Sugrue, Thomas J.

Waddell, 1987. [1987.1100.1]) 1.2 Shift change at the Ford River Rouge Plant (courtesy of the Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University) 1.3 Aerial view of Detroit’s West Side, 1937 (© Detroit News) 2.1 Typical African American neighborhood, 1942, by Arthur Siegel, United States Office of War Information (courtesy of the Library of Congress) 2.2 Black-owned home and garden plot in the Eight Mile–Wyoming neighborhood, 1942, by John Vachon, United States Farm Security Administration (courtesy of the Library of Congress) 2.3 Clearance of land for urban renewal near Gratiot Avenue and Orleans Street, on Detroit’s Lower East Side, 1951 (courtesy of the Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University) 3.1 Detroit Housing Commission map of proposed public housing projects in Detroit in the 1940s (courtesy of the Library of Congress) 3.2 Wall separating the black Eight Mile–Wyoming neighborhood from an adjacent white area in northwest Detroit, 1941, by John Vachon, United States Farm Security Administration (courtesy of the Library of Congress) 3.3 Billboard protesting black occupancy of the Sojourner Truth Homes, February 1942, by Arthur Siegel, Office of War Information (courtesy of the Library of Congress) 3.4 Black family moving into the Sojourner Truth Homes, February 1942, by Arthur Siegel, Office of War Information (courtesy of the Library of Congress) 3.5 George Edwards, Democratic candidate for mayor in 1949 (courtesy of the Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University) 4.1 Black maintenance worker in Allison Motors Plant, 1942, by Arthur Siegel, Office of War Information (courtesy of the Library of Congress) 4.2 Black sanitation workers, Detroit, mid-1950s (courtesy of the Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University) 5.1 Factory—Detroit (1955–56), by Robert Frank (Robert Frank Collection.

…

Another nonprofit, Challenge Detroit, leveraged support from major employers and launched a fellowship program to recruit about thirty emerging leaders from around the world to Detroit each year.28 The sense that gentrification, creativity, and youthful talent are the ticket to Detroit’s rebirth is one manifestation of what urbanists call the neoliberalization of the city, namely the faith that market-based solutions are more rational and efficient than democratic processes: the reliance on the private sector to provide what were once public services such as education, sanitation, and housing, and the creation of a “favorable business climate,” by weakening of labor power and workplace regulations as well as reducing taxes to attract capital. In this view, cities are locked in perpetual competition—just like business firms—and need to cut costs and create incentives to promote capital formation and growth.29 This is an old story in Detroit, one that began with public-private partnerships during the era of urban renewal (using federal funds to demolish “blighted” neighborhoods, to construct market-rate housing, and to attract new investment). This process accelerated in the 1970s and 1980s, as the city used eminent domain to clear land for redevelopment and tax incentives to attract businesses and retail downtown, like the high-rise Renaissance Center in the 1970s.

…

In 1958, the Wayne County road commissioner predicted “that little difficulty will be experienced by families facing displacement because of highway construction,” even though the families on highway sites received only a thirty-day notice to vacate and the commission made no efforts to assist families in relocation.51 Compounding the housing woes of inner-city blacks was the city’s extensive urban renewal program. The centerpiece of Detroit’s postwar master plan was the clearance of “blighted areas” in the inner city for the construction of middle-class housing that it was believed would revitalize the urban economy. Like most postwar cities, Detroit had high hopes for slum removal. City officials expected that the eradication of “blight” would increase city tax revenue, revitalize the decaying urban core, and improve the living conditions of the poorest slum dwellers.

Born in Flames

by

Bench Ansfield

Published 15 Aug 2025

The only buildings that did not burn were those that could not generate profit: public housing. In yet another irony, that enduring symbol of urban failure happened to be a far safer place to live than private rental buildings. During a decade that saw the United States swear off state-sponsored urban renewal, the arson wave was, in a sense, a free-market slum-clearance program. As in the better-remembered urban-renewal programs of the 1950s and 1960s, the market-made bulldozer precipitated massive displacement and community rupture. Yet in an era of municipal fiscal crises and state cutbacks, the blazes provoked little state action until the end of the 1970s.

…

Many watched in dismay as their heat was cut off, their plumbing became unreliable, and other essential services lapsed.20 Although insurance served to protect the interests of property holders, the industry’s withdrawal from U.S. cities was thus felt most acutely by poor communities of color, despite their lower rates of homeownership. Insurance redlining should be understood as one crucial link in a chain that has become known as the “urban crisis”: the confluence of industrial relocation, white and Black middle-class flight, the corresponding loss of a city’s tax base, ruinous urban renewal projects, blockbusting, the withdrawal of social services, and the arrival of Puerto Ricans and Black and white southerners into cities hemorrhaging manufacturing jobs. The term “urban crisis” came into vogue amid the great rebellions of the 1960s, and ever since, it has often been reduced to them.

…

Thanks to Robert Caro’s famous book about Moses, The Power Broker, the Cross Bronx Expressway is typically identified as the opening salvo in the administrative assault on the Bronx. The Power Broker’s deep probing into how the Cross Bronx Expressway carved a “One Mile” incision across the torso of the Bronx in the 1950s is still remembered as a prime example of the violent excesses of urban renewal. Displacing thousands and tearing at the fabric of Jewish community life in East Tremont, the thoroughfare reduced the neighborhood’s “very good, solid housing stock” to a mass of “ravaged hulks.” Meanwhile, the New York City Housing Authority, also under Moses’s thumb, constructed in the southern part of the borough what was once the “largest concentration of public housing anywhere in the country.”

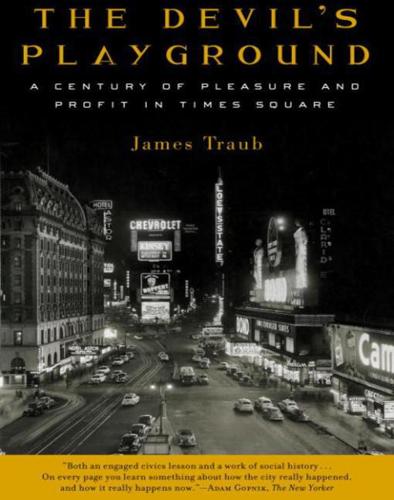

The Devil's Playground: A Century of Pleasure and Profit in Times Square

by

James Traub

Published 1 Jan 2004

“The numbers they were putting on the table for our properties were grossly inadequate.” The Brandts fought back in letters to the editor and op-ed articles; they hired a prominent social scientist to trumpet the evils of urban renewal; and they ended with a fusillade of litigation. The implacable opposition of the Brandts and other powerful real estate forces demonstrates why it was so difficult to use urban renewal laws to revitalize Times Square: the state was seizing property with great current economic value and even greater potential value. If the state had to pay what the owners considered fair value, the project would never happen.

…

And to say that you love cities is to say that you love old cities, for only cities built before the advent of the automobile have the density that makes these myriad accidents and incongruities possible. (I do not love thee, Phoenix.) Jane Jacobs, that great champion of cities and dauntless foe of urban renewal, believes in density to the exclusion of almost everything, including open space and grass. And when I think of Times Square during the epoch I am most inclined to sentimentalize—the era of Damon Runyon and A. J. Liebling, the era just before and after 42nd Street—I think of an infinitely dense and busy asphalt village, or even a series of micro-villages, such as Jacobs loves, in the space of a few blocks.

…

The prize would not necessarily go to the best or most popular idea— Alexander Parker, after all, had no plans to ask anybody whether they wanted a convention center—so the debate over the redevelopment of 42nd Street was also a struggle over who had “the public interest” at heart, and who would be able to impose that vision. It is quite possible that there were no good answers to the problem of re-creating 42nd Street. There were only answers that would disappoint different people, in different ways. ALEXANDER PARKER’S BULLDOZER approach was already becoming passé by the mid-1970s, for the excesses of “urban renewal” had convinced even the most pragmatic that cities could not survive the wholesale destruction of their history and texture. Now 42nd Street began to attract reformers who recognized that the block still had a life of its own, and who thus wanted to rejuvenate rather than flatten it. In 1976, just as Parker was wowing the business press with his grandiose plans, an advertising executive and urban gadfly named Fred Papert was establishing the 42nd Street Development Corporation in hopes of revitalizing the western end of the street.

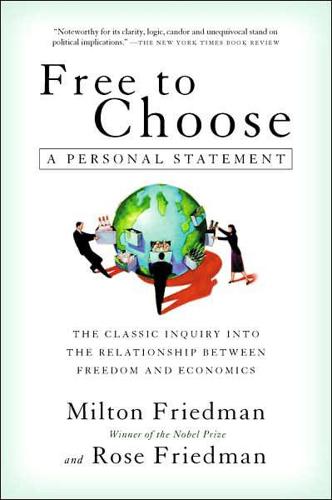

Free to Choose: A Personal Statement

by

Milton Friedman

and

Rose D. Friedman

Published 2 Jan 1980

The chief beneficiaries of public housing and urban renewal have not been the poor people. The beneficiaries have, rather, been the owners of property purchased for public housing or located in urban renewal areas; middle- and upper-income families who were able to find housing in the high-priced apartments or townhouses that frequently replaced the low-rental housing that was renewed out of existence; the developers and occupants of shopping centers constructed in urban areas; institutions such as universities and churches that were able to use urban renewal projects to improve their neighborhoods. As a recent Wall Street Journal editorial put it, The Federal Trade Commission has looked into the government's housing policies and discovered that they are driven by something more than pure altruism.

…

Spacious and luxurious apartments are rented at subsidized rates to families who are "middle-income" only by a most generous use of that term. The apartments are on the average subsidized in the amount of more than $200 per month. "Director's Law" at work again. Urban renewal was adopted with the aim of eliminating slums—"urban blight." The government subsidized the acquisition and clearance of areas to be renewed and made much of the cleared land available to private developers at artificially low prices. Urban renewal destroyed "four homes, most of them occupied by blacks, for every home it built—most of them to be occupied by middle- and upper-income whites."18 The original occupants were forced to move elsewhere, often turning another area into a "blighted" one.

…

Allen Wallis put it in a somewhat different context, socialism, "intellectually bankrupt after more than a century of seeing one after another of its arguments for socializing the means of production demolished—now seeks to socialize the results of production." 2 In the welfare area the change of direction has led to an explosion in recent decades, especially after President Lyndon Johnson declared a "War on Poverty" in 1964. New Deal programs of Social Security, unemployment insurance, and direct relief were all expanded to cover new groups; payments were increased; and Medicare, Medicaid, food stamps, and numerous other programs were added. Public housing and urban renewal programs were enlarged. By now there are literally hundreds of government welfare and income transfer programs. The Department of Health, Education and Welfare, established in 1953 to consolidate the scattered welfare programs, began with a budget of $2 billion, less than 5 percent of expenditures on national defense.

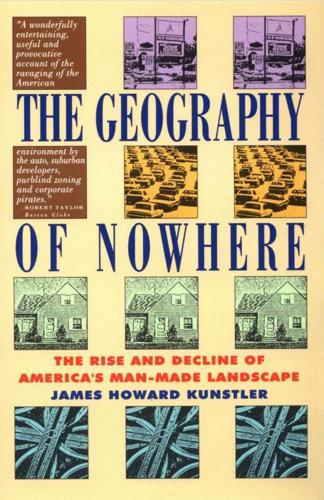

The Geography of Nowhere: The Rise and Decline of America's Man-Made Landscape

by

James Howard Kunstler

Published 31 May 1993

Meanwhile, the hotel's main entrance on the parking lot side of the building is connected to the life of the town only by cars. Facing this main entrance are blocks and blocks that were designated an urban renewal zone in the 1960s. Here stood little stores with dwellings up stairs (i. e . , affordable housing), public amenities like saloons and lunch rooms, and even a sprinkling of small factories or workshops. Here lived the shop clerks, laborers, small artisans, and in some cases the owner of the business below. All the urban renewal blocks on each side of Broadway were turned into parking lots. In twenty years, not a single new building has gone up on them. As a result the business district has been reduced pretty much to one street : Broadway.

…

In fact, part of the Corbu doctrine of the Esprit Nouveau, as filtered through Corbu Purism, was a rejection of decorative art per se. Except that for all his rejection of decorative art, his pavilion ended up being about style anyway : the style of no style. In a decade preoccupied with glamour, what could be more chic? The pavilion held another curiosity : an exhibit of Le Corbusier's Plan Voison, a fanciful urban renewal scheme to bulldoze the Marais district of Paris-a massive historic chunk of the city a stone's throw from the Louvre that included the Place de Bastille and the old Palais Royale (Place de Vosges )-and replace it with a gargantuan "Radiant City" complex of twenty-four sixty-story high-rises set amid parklike grounds and served by limited-access automobile roads.

…

In a peculiar way, /America seemed eager to emulate the postwar devastation of European \cities, to envy their chance to clear away the rubble and begin again. Bulldozing the entire downtown of a Worcester, Massachusetts, or a 7 8 _ Y E S T E R D A Y ' S T O M O R R O W New Haven, Connecticut, and starting over from scratch, didn't seem like such a bad idea. Americans certainly did not respond to the postwar "urban renewal" schemes with anything like the gape-mouthed horror of Parisians contemplating Corbu's plan Voison in 1925. Finally, the Radiant City appealed to all the latent Arcadian yearnings in our culture. It was the old romantic idea-going back to William Penn---of combining the urban with the rural, of living close to nature, of creating a city out of buildings in a park.

The power broker : Robert Moses and the fall of New York

by

Caro, Robert A

Published 14 Apr 1975

By 1957, $133,000,000 of public monies had been expended on urban renewal in all the cities of the United States with the exception of New York; $267,000,000 had been spent in New York. So far ahead was New York that when scores of huge buildings constructed under its urban renewal program were already erected and occupied, administrators from other cities were still borrowing New York's contract forms to learn how to draw up the initial legal agreements with interested developers. When Moses resigned from his urban renewal directorship in i960, urban renewal had produced more physical results in New York than in all other American cities combined.

…

In 1949, the federal government enacted a new approach to the housing problems of cities: urban renewal. The approach was new both in philosophy —for the first time in America, government was given the right to seize an individual's private property not for its own use but for reassignment to another individual for his use and profit—and in scope: a billion dollars was appropriated in 1949 and it was agreed that this was only seed money to prepare the ground for later, greater plantings of cash. Most cities approached urban renewal with caution. But in New York City, urban renewal was directed by Robert Moses. By 1957, $133,000,000 of public monies had been expended on urban renewal in all the cities of the United States with the exception of New York; $267,000,000 had been spent in New York.

…

Says the federal official in charge of the early years of the program: "Because Robert Moses was so far ahead of anyone else in the country, he had greater influence on urban renewal in the United States—on how the program developed and on how it was received by the public—than any other single person." Parks, highways, urban renewal—Robert Moses was in and of himself a formative force in all three fields in the United States. He was a seminal thinker, perhaps the single most influential seminal thinker, in developing policies in these fields, and the innovator, perhaps the single most influential innovator, in developing the methods by which these policies were implemented. And since parks, highways and urban renewal, taken together, do so much to shape cities' total environment, how then gauge the impact of this one man on the cities of America?

The Great Reset: How the Post-Crash Economy Will Change the Way We Live and Work

by

Richard Florida

Published 22 Apr 2010