The Problem With Work: Feminism, Marxism, Antiwork Politics, and Postwork Imaginaries

by

Kathi Weeks

Published 8 Sep 2011

The text was published as a pamphlet, the second edition of which includes four texts: an introduction by James, dated July 1972; the title essay by Dalla Costa, completed in December 1971, first published in Italian in 1972 as “Donne e sovversione sociale” (Women and the Subversion of the Community), and translated the same year into English by Dalla Costa and James; an essay by James, “A Woman’s Place,” first published in 1953; and a brief “Letter to a Group of Women,” signed by Dalla Costa, James, “and many others.” My discussion is confined to the first two essays, as they are most relevant to the development of the wages for housework perspective. Besides this pamphlet, I draw most heavily, though not exclusively, on the following contributions to the wages for housework literature: Federici (1975), Cox and Federici (1976), and James (1976). 9. On the relation between wages for housework and autonomist Marxism, see Cleaver (2000). On the relationship between the Italian wages for housework movement and specific groups associated with the autonomist tradition (including Potere Operaio and Midnight Notes), see Dalla Costa (2002).

…

In this chapter, I present a reading of the 1970s feminist demand for wages for housework and then propose its reconfiguration as a contemporary demand for a guaranteed basic income. As will soon become clear, the wages for housework perspective—as it was articulated in a handful of texts published in Italy, Britain, and the United States between 1972 and 1976—is an important inspiration for many of the arguments in subsequent chapters as well.1 Indeed, the two major demands often repeated by proponents of wages for housework, along with other autonomists—for more money and for less work—guide the choice of demands that are the subject of this chapter and the next: the demand for basic income and the demand for shorter hours.

…

One of the limitations of such an account is, of course, its reductionism—a perhaps inevitable side effect of any such classificatory project. In the case that concerns me here, wages for housework is contained in the broader category of Marxist feminism, which is in turn inserted into a progressive historical narrative as one moment in a dialectical chain.3 But the more difficult problem is not that this narrative codes wages for housework as a political vision that failed and was defeated; the trouble is that wages for housework is imagined as part of a history that has been superseded. That is why a return to this 1970s tradition might be understood not only as a distraction, but as a regression, as a return either to the mistakes that were made before socialist feminism’s subsumption of Marxist feminism, or to a thoroughly repudiated and now overcome essentialist feminism.

Revolution at Point Zero: Housework, Reproduction, and Feminist Struggle

by

Silvia Federici

Published 4 Oct 2012

Many times the difficulties and ambiguities that women express in discussing wages for housework stem from the fact that they reduce wages for housework to a thing, a lump of money, instead of viewing it as a political perspective. The difference between these two standpoints is enormous. To view wages for housework as a thing rather than a perspective is to detach the end result of our struggle from the struggle itself and to miss its significance in demystifying and subverting the role to which women have been confined in capitalist society. When we view wages for housework in this reductive way we start asking ourselves: what difference could more money make to our lives?

…

The Revolutionary Perspective If we start from this analysis we can see the revolutionary implications of the demand for wages for housework. It is the demand by which our nature ends and our struggle begins because just to want wages for housework means to refuse that work as the expression of our nature, and therefore to refuse precisely the female role that capital has invented for us. To ask for wages for housework will by itself undermine the expectations that society has of us, since these expectations—the essence of our socialization—are all functional to our wageless condition in the home. In this sense, it is absurd to compare the struggle of women for wages for housework to the struggle of male workers in the factory for more wages.

…

By the time I read the last page, I knew that I had found my home, my tribe and my own self, as a woman and a feminist. From that also stemmed my involvement in the Wages for Housework campaign that women like Mariarosa Dalla Costa and Selma James were organizing in Italy and Britain, and my decision to start, in 1973, Wages for Housework groups in the United States. Of all the positions that developed in the women’s movement, Wages for Housework was likely the most controversial and often the most antagonized. I think that marginalizing the struggle for wages for housework was a serious mistake that weakened the movement. It seems to me now, more than ever, that if the women’s movement is to regain its momentum and not be reduced to another pillar of a hierarchical system, it must confront the material condition of women’s lives.

Capitalism and Its Critics: A History: From the Industrial Revolution to AI

by

John Cassidy

Published 12 May 2025

Georgescu-Roegen, “Energy and Economic Myths,” 379. 24. Silvia Federici and Wages for Housework 1. Silvia Federici and Arlen Austin, eds., Wages for Housework: The New York Committee 1972–1977: History, Theory, Documents (Brooklyn, NY: Autonomedia, 2018), 87–89. 2. Federici and Austin, Wages for Housework, 91. 3. Federici and Austin, Wages for Housework, 41. 4. Betsy Warrior, Strike! While the Iron Is Hot! Wages for Housework, poster, 48.2 × 35.5 cm, Yanker Poster Collection, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2015649375. 5. Federici and Austin, Wages for Housework, 121–22. 6. See, e.g., “The International Wages for Housework Campaign” (newsletter), https://freedomarchives.org/Documents/Finder/DOC500_scans/500.020.Wages.for.Housework.pdf; and “International Lesbian Conference,” Power of Women: Magazine of the International Wages for Housework Campaign, no. 5 (1975), https://bcrw.barnard.edu/archive/lesbian/Power_of_Women.pdf. 7.

…

She also did historical research on the origins of the gendered division of labor, which turned into an influential 1984 book The Great Caliban: History of the Rebel Body in the First Phase of Capitalism, cowritten with Leopoldina Fortunati, an Italian feminist theorist. In 1978, Dalla Costa’s Padua branch of Wages for Housework also shut down. Other parts of the movement carried on, including the International Wages for Housework Campaign and Black Women for Wages for Housework. But the shuttering of the New York Committee and the Wages for Housework branch in the Italian city where the movement had been founded marked an ending of a sort. * * * Like many radical movements, Wages for Housework didn’t achieve its primary goals and ended up splintering. That doesn’t mean it failed. Initially, the idea that domestic labor was productive in an economic sense because it helped to maintain and reproduce the capitalist workforce ran into resistance from some leftist intellectuals.

…

Dalla Costa and James, Power of Women, 43. 22. Dalla Costa and James, Power of Women, 49. 23. Federici and Austin, Wages for Housework, 30. 24. Federici and Austin, Wages for Housework, 18. 25. Federici and Austin, Wages for Housework, 46. 26. Federici and Austin, Wages for Housework, 20. 27. Federici, Wages Against Housework, 2–3. 28. Federici, Wages Against Housework, 6. 29. Federici, Wages Against Housework, 5. 30. “Theses on Wages for Housework,” in Federici, Wages Against Housework, 32. 31. Selma James, “A Woman’s Place,” February 1953; originally published in the workers’ newspaper Correspondence, https://anth1001.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/james_a-womans-place.pdf. 32.

Care: The Highest Stage of Capitalism

by

Premilla Nadasen

Published 10 Oct 2023

Her goal was to expand class analysis to consider the many unwaged workers, including housewives, colonial subjects, and enslaved people, who contributed to capitalist wealth. The pamphlet, apparently, was “selling like hotcakes.”41 Shortly after the Manchester conference, activists formed the International Wages for Housework Campaign. Led by James and socialist feminists Mariarosa Dalla Costa, Silvia Federici, and Margaret Prescod, who founded and led the Black Women for Wages for Housework, the movement had bases in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Italy. In contrast to other feminists of the period, Wages for Housework activists saw paid employment outside the home as simply another form of exploitation rather than a source of liberation for women.42 As James and Dalla Costa wrote in The Power of Women and the Subversion of the Community in 1972, women must “refuse the myth of liberation through work.”43 The movement had as a central goal not only compensating housewives and expanding the analysis of unwaged work, as James argued, but also transforming household and gender relations and the supposed “natural” role of women in the domestic sphere.

…

In that regard, the movement subverted dominant capitalist norms and attributions of worth. The Wages for Housework movement and the welfare rights movement helped shift the political terrain of class struggle to the domestic sphere. They believed that the labor performed by mothers was economically and socially valuable and should be compensated by the state. Although the Wages for Housework movement rejected the language of love and care for their own families, welfare rights activists rooted their claim to assistance in that language. Wages for Housework activists were speaking to women for whom the language of love was deployed to coerce them to provide unpaid care.

…

See also labor movement United Health Group, 167 United Nations Human Rights Office, 150–51 unpaid household labor, 28, 50–52 passim, 89–90, 92, 144. See also Wages for Housework movement US Bureau of Indian Affairs. See Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) US Department of Health and Human Services, 169 US Department of Homeland Security, 87 US Department of State: visa system, 84–85, 86–87, 89 visa system, 84–85, 86–87, 89 wage labor and wages, 50, 51, 59, 78, 101, 103; women’s, 92. See also living wage; minimum wage Wages Against Housework (Federici), 121, 127 Wages for Housework movement, 120–22, 125 Walia, Harsha, 191 War on Poverty, 11, 126, 137 Washing Society (washerwomen), 105 wealth inequality, 151 Weeks, Kathi, 214 welfare, 129–40, 143, 155; HB2 visa workers and, 87; Mississippi fraud, 157–58, 169–70.

Work Won't Love You Back: How Devotion to Our Jobs Keeps Us Exploited, Exhausted, and Alone

by

Sarah Jaffe

Published 26 Jan 2021

The left, having embraced the idea that going to work was liberation, had little with which to counter this turn. 49 But one group of feminists, inspired by the NWRO and the Italian Marxist operaismo (workerism) movement of the 1970s, put forward a different analysis, one that challenged popular ideologies of both work and the family. While the Wages for Housework Campaign, as a demand and a political perspective, didn’t spread as far as its founders would have liked, its organizers continue to struggle and to inspire others to this day. 50 Wages for Housework picked up the idea from operaismo that capitalist production has subsumed every social relation, collapsing the distinction between “society” and “workplace” and turning all of those relations into relations of production. To the organizers of Wages for Housework, the “social factory” began in the home, and the work done in the home was necessary for the functioning of capitalism because it reproduced workers for capital.

…

The women of Wages for Housework noted that the state pays foster parents, and that courts had granted damages to men whose wives had been injured to pay for “lack of services.” 55 The new discourse of the labor of love was being knitted together as wages were dropping and factories were closing, moving, and automating. Those in the Wages for Housework movement were some of the first to see what was happening in the 1970s. The shifts in the economy became visible in New York and other cities, where a fiscal crisis laid the groundwork for later austerity politics. Wages for Housework proponents warned, Cassandra-like, that feminists were going into the workplace just as the bottom was falling out of it.

…

Women who worked in child care and hospitals noted that the devaluing of work in the home led to a devaluing of their work outside of it. Violence against women, they argued, was a form of work discipline, a boss keeping his subordinates in line. Wages for Housework was a perspective that could be applied to all political struggles—it added an angle that was missing in most analyses of capitalism and gender. 54 Though many people laughed (and continue to laugh) at the idea of wages for housework, it is inarguably true that housework, in many instances, is in fact paid. As economist Nancy Folbre wrote, echoing those welfare rights organizers, “if two single mothers, each with two children under the age of five, exchanged babysitting services, swapping children for eight hours a day, five days a week, and paying one another the federal minimum wage of $7.25 an hour, they could both take full advantage of [the Earned Income Tax Credit], receiving a total of more than $10,000 for providing essentially the same services they would provide for their own children.”

Bullshit Jobs: A Theory

by

David Graeber

Published 14 May 2018

Candi had come around from Wages for Housework to UBI for similar reasons. She and some of her fellow activists started asking themselves: Say we did want to promote a real, practical program, what would that be? Candi: The reaction we used to get on the street when we leafleted for Wages for Housework was, either women would say, “Great! Where can I sign up?” or they’d say, “How dare you demand money for something I do for love?” That second reaction wasn’t entirely crazy, these women were understandably resistant to commodifying all human activity in the way that getting a wage for housework might imply. Candi was particularly moved by the arguments of the French Socialist thinker André Gorz.

…

She is involved in the movement for Universal Basic Income, which calls for replacing all means-tested social welfare benefits with a flat fee to be paid to everyone, equally, residing in the country. Candi, a fellow Basic Income activist—who also held a useless job in the system whose details she preferred not to disclose—told me she originally became interested in such issues when she first moved to London in the 1980s and became part of the International Wages for Housework Movement: Candi: I got involved in Wages for Housework because I felt that my mother needed it. She was trapped in a bad marriage, and she would have left my dad a lot earlier if she’d had her own money. That’s something really important for anyone in an abusive or even just boring relationship: to be able to get out of it without being financially impacted.

…

Most women’s labor was placed in the latter category, despite the fact that without it, the very machine that stamped it as “not really work” would grind to a halt immediately. Wages for Housework was essentially an attempt to call capitalism’s bluff, to say, “Most work, even factory work, is done for a variety of motives; but if you want to insist that work is only valuable as a marketable commodity, then at least you can be consistent about the matter!” If women were to be compensated in the same way as men then a huge proportion of the world’s wealth would instantly have to be handed over to them; and wealth, of course, is power. What follows is from a conversation with both of them: David: So inside Wages for Housework, were there many debates about the policy implications—you know, the mechanisms through which the wages would actually be paid?

Border and Rule: Global Migration, Capitalism, and the Rise of Racist Nationalism

by

Harsha Walia

Published 9 Feb 2021

Ghodsee, “Women’s Unpaid Labor Is Worth $10,900,000,000,000,” New York Times, March 5, 2020, www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/03/04/opinion/women-unpaid-labor.html. 47.Maria Mies, Patriarchy and Accumulation on a World Scale: Women in the International Division of Labour (London: Zed Books, 1998), 116. 48.Patricia Hill Collins, Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment (New York: Routledge, 2000), 47. 49.“The International Wages for Housework Campaign,” Freedom Archives, https://freedomarchives.org/Documents/Finder/DOC500_scans/500.020.Wages.for.Housework.pdf. 50.Ella Baker and Marvel Cooke, “Bronx Slave Market,” The Crisis 42, no. 11 (November 1, 1930): 330-32. 51.Claudia Jones, An End to the Neglect of the Problems of the Negro Woman! (National Women’s Commission, 1949), republished on New Frame, www.newframe.com/from-the-archive-an-end-to-the-neglect-of-the-problems-of-the-negro-woman/. 52.Jones, An End to the Neglect. 53.Jones, An End to the Neglect. 54.Association of Black Women Historians, “An Open Statement to the Fans of The Help,” August 12, 2011, http://abwh.org/2011/08/12/an-open-statement-to-the-fans-of-the-help/. 55.Eileen Boris and Premilla Nadasen, “Domestic Workers Organize!”

…

See also Hindutva Africa and, 71 CAA in, 190 caste in, 175–176 far right in, 9, 169, 171–178, 189 Islamophobia in, 175 kafala system and, 151–153 Kashmir and, 98, 172, 177, 192 Look East policy, 192 migrants from, 136 Muslim people in, 171–174, 178, 189–191 Myanmar and, 191–192 NRC in, 189–190 statelessness in, 9, 189–190 World Bank and, 70 India–Bangladesh border, 178 Indiana, 29 Indian Act, 83 Indian Citizenship Act, 25 Indian Ocean, 148, 150 Indian Removal Act of 1830, 24 Indian Wars, 24, 26, 78 Indigenous people, xix, 171, 186, 195, 196, 205, 209–211, 215, 218–219 debt and, 65 far right and, 9 free trade agreements and, 49, 51 gender and, 24–25, 27, 50–51 in Australia, 95–96 in Bolivia, 218 in Brazil, 180–182 in Canada, 1, 25, 73, 82–83, 156, 158–160, 162, 164 in Central America, 27, 43, 73 in Honduras, 44, 45 in Latin America, 27 in Mexico, 25, 27, 50–51 in Nauru, 98 in Papua New Guinea, 94–95, 98 in Spain, 112 in the United States, xvii, 13, 21–28, 32–33, 35–36, 82, 84, 200, 212–213 resource colonialism and, 95 surveillance of, 57 Indonesia, 73, 100–101, 136, 147, 151, 165, 187, 214 Industrial Police, 62 Industrial Workers of the World, xviii, 34–35, 85 Instacart, xv, 214 Institute of Race Relations, 119 Intercede, 165 International Black Women for Wages for Housework, 141 International Civil Liberties Monitoring Group, 57 International Court of Justice, 97 International Democratic Union, 170 International Domestic Workers Federation, 144 International Finance Corporation, 70 International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance, 173 International Labour Organization, 133, 138, 142, 144 International Monetary Fund, 49, 63–64, 113, 121, 143 International Organization for Migration, 66, 86, 106, 120 International Trade Union Confederation, 145, 152 International Wages for Housework, 141 Inuit people, 186 Ipili people, 94–95 Iran, 60, 88, 93, 122, 149 Iran-Contra scandal, 44 Iraq Blackwater in, 4 drone strikes in, 60 Kuwait and, 193 migrant workers in, 135–136 Muslim ban and, 60 refugees from, 20, 57, 100, 106, 114, 116 troops redeployed from, 109 US Border Patrol in, 3, 36, 89 US invasion of, 56 Ireland, 111 Irish people, 95 Irom Sharmila, 176 ISIS, 56 Islam, 126, 148, 150, 187–188 Islamophobia, 159, 197, 205.

…

—Migrant worker in Qatar, quoted in Amnesty International, “My Sleep Is My Break”: Exploitation of Migrant Domestic Workers in Qatar The five features of migrant worker programs are exemplified in domestic work, where a growing proportion of workers are migrants in gendered, sexualized, and racialized positions of precarity. The unevenly gendered work of the social reproduction of labor within the domestic sphere, an essential condition for the reproduction of capitalism, means the private domain of the home has long been a site of struggle to make this feminization of labor visible. The International Wages for Housework campaign in the 1970s, led by Marxist feminists, demanded that class struggle include women’s unpaid domestic labor as a pillar of patriarchal cisheteronuclear organization and capitalist accumulation. While the slogan focused on wages, the campaigners made clear it was a rhetorical device to make housework visible and highlight patriarchal social structuring under capitalism.

All Day Long: A Portrait of Britain at Work

by

Joanna Biggs

Published 8 Apr 2015

With the British writer Selma James, who I’d seen trailed by a black and a white dog at the ECP’s offices when I went to interview Ina, Federici set up the Wages for Housework Campaign, which continues to this day. Instead of agitating for more waged labour, to put another crack in the glass ceiling and occupy another board seat, women would redefine what work is: Why is writing an email work and feeding a baby not work? Friedan and Wages for Housework came up with two different solutions to the problem, but they agreed on its nature. It wasn’t the cooking and cleaning; it was the ‘smiling and fucking’ – the emotional labour service work also calls for – as well as the pretence that it was offered happily that made the work unbearable.

…

Sex has been linked to servitude for a long time: Samuel Richardson’s 1740 novel of seduction, Pamela, showed how serving a master in the dining room might slide into serving him in the bed chamber; in the mid-nineteenth century a Salvation Army register showed that 88 per cent of prostitutes they helped had once been domestic servants. The service industry employed 44 per cent of the British workforce in 1948, and employs 85 per cent of it today. All kinds of workers in all kinds of jobs are now encouraged to create an experience out of an ordinary transaction – the smiling and fucking that the Wages for Housework campaign identified as worthy of payment – and we are only just beginning to understand what sort of experience of work the service economy allows. The way emotions are used at work is something sex workers understand better than most of us. Ina is used to changing how others feel: judging the emotional state of the customer, calming him down, relaxing him.

…

Eleven years later, Silvia Federici, a writer and activist informed by the Italian Autonomist tradition, came up with a more radical answer to the same problem. She agreed that housework turned women into something less than servants: ‘We are seen as nagging bitches, not workers in struggle,’ she wrote in the 1974 pamphlet Wages for Housework. ‘We are housemaids, prostitutes, nurses, shrinks; this is the essence of the “heroic” spouse who is celebrated on “Mother’s Day”. We say: stop celebrating our exploitation, our supposed heroism. From now on we want money for each moment of it, so that we can refuse some of it and eventually all of it.’

Inventing the Future: Postcapitalism and a World Without Work

by

Nick Srnicek

and

Alex Williams

Published 1 Oct 2015

In other words, the nature of work would become a measure of its value, not merely its profitability.114 The outcome of this revaluation would also mean that, as wages for the worst jobs rose, there would be new incentives to automate them. UBI therefore forms a positive-feedback loop with the demand for full automation. On the other hand, a basic income would not only transform the value of the worst jobs, but also go some way towards recognising the unpaid labour of most care work. In the same way that the demand for wages for housework recognised and politicised the domestic labour of women, so too does UBI recognise and politicise the generalised way in which we are all responsible for reproducing society: from informal to formal work, from domestic to public work, from individual to collective work. What is central is not productive labour, defined in either traditional Marxist or neoclassical terms, but rather the more general category of reproductive labour.115 Given that we all contribute to the production and reproduction of capitalism, our activity deserves to be remunerated as well.116 In recognising this, the UBI indicates a shift from remuneration based upon ability to remuneration based upon basic need.117 All the genetic, historical and social variations that make effort a poor measure of a person’s worth are rejected here, and instead people are valued simply for being people.

…

It enables experimentation with different forms of family and community structure that are no longer bound to the model of the privatised nuclear family.119 And financial independence can reconfigure intimate relationships as well: one of the more unexpected findings of experiments with UBI has been that the divorce rate tended to rise.120 Conservative commentators jumped on this as proof of the demand’s immorality, but higher divorce rates are easily explained as women gaining the financial means to leave dysfunctional relationships.121 A basic income can therefore enable easier experimentation with the family structure, more possibilities for the provision of childcare and an easier transformation of the gendered division of labour. Moreover, unlike the demand for ‘wages for housework’ in the 1970s, the demand for UBI promises to break out of the wage relation rather than reinforce it. While a universal basic income may appear economically reformist, its political implications are therefore significant. It transforms precarity, it recognises social labour, it makes class power easier to mobilise, and it extends the space in which to experiment with how we organise communities and families.

…

Paul Cockshott and Allin Cottrell, Towards a New Socialism (Nottingham: Spokesman, 1993), p. 27; Karl Marx, Critique of the Gotha Program (New York: International, 1966), pp. 8–10. 118.Weeks, Problem with Work, p. 149. 119.Mckay and Vanevery, ‘Gender, Family, and Income Maintenance’, p. 280. 120.Hum and Simpson, ‘A Guaranteed Annual Income?’, p. 81. 121.This is one reason why the UBI is a better demand than that of wages for housework. Weeks, Problem with Work, p. 144. 122.Raventós, Basic Income, Chapter 8; Chancer, ‘Benefitting from Pragmatic Vision, Part I’, pp. 120–2; Guy Standing, ‘The Precariat Needs a Basic Income’ Financial Times, 21 November 2013; Gorz, Paths to Paradise, p. 45. 123.For an eloquent polemic against the work ethic, see Federico Campagna, The Last Night: Anti-Work, Atheism, Adventure (Winchester: Zero, 2013). 124.Steensland, Failed Welfare Revolution, pp. 13–18. 125.Ibid., p. 17. 126.Pierre Dardot and Christian Laval, The New Way of the World: On Neoliberal Society, transl.

Squeezed: Why Our Families Can't Afford America

by

Alissa Quart

Published 25 Jun 2018

The American artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles wrote in a 1969 manifesto: “The culture confers lousy status on maintenance jobs = minimum wages, housewives = no pay/clean your desk, wash the dishes, clean the floor, wash your clothes, wash your toes, change the baby’s diaper, finish the report, correct the typos, mend the fence, keep the customer happy.” Ukeles turned her own exhaustion and frustration at the devaluing of her labor and the labor of those around her into poetry and performance art. In the 1970s, Wages for Housework amplified Ukeles’s aesthetic impulse into an unsparing movement. Wages for Housework argued that caring for one’s own children and cleaning one’s own home should be compensated and politically and emotionally recognized. Italian-born Silvia Federici was one of the movement’s central figures. Federici, now a mild-mannered professor of seventy-three who lives in Park Slope, spoke with me in a hypnotic lilt, but she remained obsessed with rescuing women from drudgery and also with the ongoing undervaluation of domestic work for hire.

…

See Labor unions Universal basic income (UBI), 240–45, 256–57 Universal pre-K, 82–84, 254–56 University of California, Berkeley, 97, 101 University of California, Los Angeles, 137 University of California, San Diego, 128 University of Chicago, 39, 97 University of Kentucky, 35 University of Massachusetts Amherst, 17, 73, 169 University of Pennsylvania, 151 University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Presbyterian Shadyside, 225–26, 239 University of Stirling, 93 University of Toronto, 16 University of Warwick, 90 University of Wisconsin, 258–59 UPMC Shadyside Hospital, 225–26, 239 Upper-middle class, 89–110 Ainsley Stapleton’s story, 98–99 health outcomes and, 93–94, 96–97 law school graduates, 101–10 Shaun Tanner’s story, 89–90, 93, 109 social status and, 90–94 Upstairs, Downstairs (TV show), 209, 291n Upward social mobility. See Social mobility Urban Outfitters, 71 U.S. News & World Report, 55 Valencia College Peace and Justice Institute, 105 Vanity Fair, 211 Very Hungry Caterpillar (Carle), 7 Wages for Housework, 129–30 Wage stagnation, 9, 60–61, 243 Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 177 Wayne, Christina, 219 “Wealthies” vs. selfies, 216 “Wealthy Hand-to-Mouth, The” (study), 96–97 Weather Underground, 89 We Believe the Children: A Moral Panic in the 1980s (Beck), 75 Weber, Max, 60 Weeks, Kathi, 242 Weldon, Fay, 291n Westwood College, 41 WeWork, 38–39 Wharton, Edith, 94 Whitehall Studies, 96 Who Cares Coalition, 254 Wilkinson, Will, 213 William Cullen Bryant High School, 144–45 Williams, Joan, 29 Williams, William Carlos, 40 “Will to education,” 133 Wire, The (TV show), 217 Wolcott, James, 211 Women Have Always Worked (Kessler-Harris), 112–13, 123–24 Worker cooperative movement, 157–60, 259–60 Work-life balance, 13–14, 251 Work schedules, 5, 68–72 extreme day care and, 64–66, 68–74, 78–79 remedies, 84–86 Workweek, 73–74, 84–85 of average American adult, 65, 71 rise of 24/7 day care, 64–65 World Economic Forum (WEF), 227–28 World of Homeowners, A (Kwak), 128 Xanax, 45, 62 Yale University, 48 YouTube, 214, 222 Zelizer, Viviana, 77 Zimmerman, Martín, 218 Zūm, 70 Zunshine, Lisa, 48 Zutano, 257 About the Author ALISSA QUART is the executive editor of the Economic Hardship Reporting Project, a journalism nonprofit with Barbara Ehrenreich.

A History of the World in Seven Cheap Things: A Guide to Capitalism, Nature, and the Future of the Planet

by

Raj Patel

and

Jason W. Moore

Published 16 Oct 2017

The world’s largest market for wombs is India, where a service that costs $80,000 to $100,000 in the Global North can be had for $35,000 to $40,000 in an industry expected to reap profits in excess of $2 billion in India alone.85 The frontier of cheap care has deepened and expanded, with vast international networks of care service providers remitting funds across borders to help sustain households elsewhere. The global household has always done the work that makes possible the global factory and the global farm. One radical response to the fundamental devaluation of care work involves a jujitsu pricing move and the demand that housework be paid. As the 1970s Wages for Housework campaign argued, “Slavery to an assembly line is not a liberation from slavery to a kitchen sink. To deny this is also to deny the slavery of the assembly line itself, proving again that if you don’t know how women are exploited, you can never really know how men are.”86 The irony here, of course, is that there’s a long history of women who were paid little if at all for their domestic labor: those working under slavery.

…

The United States is not alone in this pattern, with carers from different classes, castes, and indeed nations suffering widespread exploitation in other countries too.87 And even if payment were a route to recognition, there’s much further to go to reach dignity. As Angela Davis put it, “Psychological liberation can hardly be achieved simply by paying the housewife a wage.”88 Yet the insight of Wages for Housework shouldn’t be forgotten. To ask for capitalism to pay for care is to call for an end to capitalism. If introducing money into this ecological relation doesn’t guarantee success, perhaps more collective approaches might work. Although states have been there from the creation of the modern household, their role in managing care dramatically increased after the Second World War and the fight for the creation of the welfare state.89 That welfare state—especially in Western Europe—delivered meaningful gains for working classes in health care, education, and pensions.

…

See also British empire; England United States, xiv map 1; agricultural exports, 103–4; banking in, 77; care work, 134, 135–36; food consumption, 33; fossil fuel think tanks, 41; gold standard, 146, 176; human community/exclusion in, 38; Indigenous Peoples, 200; oil industry, 37, 131, 176; reproductive labor in, 132–33; Southern cotton industry, 103; sugar consumption, 34; supremacism in, 41; worker control in, 108 Valladolid controversy, 36–37, 92–94 value: of care work, 137; cheapness and, 21–22, 24; defined, 101–2; gold standard and, 146; of pensions, 136; of reproductive labor, 32; surplus value production, 95; of time, 99; use values, 95; of work, 97 Venice, 74, 77, 222n30 Virunga National Park, DRC, 237n93 Volcker Shock, 69–70, 177 Voser, Peter, 166 Voss, Barbara, 114–15 wages: unequal by gender, 31; unions for higher wages, 41, 42; wage repression, 153 Wages for Housework campaign, 135 Walker, Alice, on activism, 42 Wallerstein, Immanuel, 25–26 war debt: captives and, 65–66; financing of, 66, 69; profitability decline and, 27–28; war financing, 78–81 web of life: changes in, 22–24; conceptual tools and, 40; energy and, 165; expansion within, 27; and human power, 47–48; work and, 102–3; world-ecology perspective and, 38 Weis, Tony, 155, 174 welfare state, 41, 135 Westoby, Jack, 74 witches: Chichimec woman, 44–45, 209–10; as cultural intervention, 31, 231n97; and land mapping, 61 Wolf, Eric, 147 women: bread riots, 144; captains’ wives, lack of written record on, 217n92; category creation, 128–131; cheap nature and, 53–54; control mechanisms, 61; domestic labor, 31–32, 41; encomienda system, 51; exclusion of, 24, 128; expulsions of, 39; gender equality increases, 131; Pan y Rosas movement, 206; policing of, 31; reproductive labor value, 32; reproductive policing, 217n92; time demands on, 230–31n79; unequal wages, 31; voting rights, 230n63; the witch, 217n96; witch burning, 31; women’s rights, 131, 131–32, 135–36.

The Costs of Connection: How Data Is Colonizing Human Life and Appropriating It for Capitalism

by

Nick Couldry

and

Ulises A. Mejias

Published 19 Aug 2019

Being paid for one’s data would, in any case, do nothing to address the damage done by the continuous surveillance on which data collection is built (see chapter 5). The same goes for Morozov’s proposal for collective ownership of data assets (“After the Facebook Scandal”). 124. Contrast the wages-for-housework argument of 1970s and 1980s feminists (Federici, Wages, 4; Delphy, Close to Home), which had the goal not of commodifying that work but of “denaturalizing” capitalism’s wider social relations so as to challenge them for the longer term. So it is today with platforms: the key issue is not securing payment but denaturalizing the abstraction of social relations through data whereby capitalism is able to expand ever deeper into the social world. 125.

…

B., 157 Duggan, Maeve, 248n120 Dussel, Enrique, 111, 157, 163, 203 Dutch East India Company, 95–96 Dyer-Witheford, Nick, 12 East India Company (British), 97–101, 109 Echo (Amazon), 23, 133 “ecologies,” 109, 262n22 economic issues: behavioral economics, 140, 249n145; China’s GDP growth, 104; data and emerging social order of capitalism, 19; economic value extracted from data, 7–12; economic violence, 106–8; generated by connection, 7; of gig economy, 13, 59–63, 108; ICT sector and GDP, 235–36n58; market capitalization of cloud computing companies, 37–38; market societies’ creation, 116–17; neuroeconomics, 141; relations between state and, 13; social interaction embedded in, 86; unequal global distribution of economic power, 14–15; wages-for-housework argument, 230n124. See also information and communication technologies sector; oil and gas sector; social quantification sector; specific names of countries education sector, and autonomy, 175–76 Eggers, Dave, 164–66, 255n45 Electronic On-Board Recorders (EOBRs), 153 Elkin-Koren, Niva, 147 employment.

…

See also social knowledge Sweeney, Latanya, 174 Taplin, Jonathan, 59 Tarde, Gabriel, 142, 250n157 Taser (Axon AI), 53, 134, 145, 213, 262n22 Tasmanian people, and historical colonialism, 79 technological advance: and change to human life, x; Marx on, 233n12; and postcolonialism, 240n38; profit and effect of, 40; railroads, 98–101; “technium,” 158; “technocratic paradigm,” 262n28 telematics, 65 Tencent: colonial ideology of, 17; data and emerging social order of capitalism, 19, 24, 26; data as colonized resource by, 7; internal colonizing and social quantification sector, 55–57; market-capitalization value of, 37 terra nullius doctrine, 9 “tethered” devices, 15 Thaler, Richard, 139–40 Thatcher, Jim, 223n2 The Mediated Construction of Reality (Hepp, Andreas), 228n94 “thingification,” 77 “This Is America” (Glover), 153 Today (BBC Radio 4), 221n18 “tool reversibility,” 228n94 Toyota, 54 Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement (TPP), 105 Tresata, 89 Tuck, Eve, xi Turkers, 59–60 Turow, Joseph, 132 Twitter, 236n58 Uber, 13, 54, 61–62, 115, 236n58 Undoing the Demos (Brown), 231n135 United Kingdom: child abuse monitoring by, 145; counterhistories of, 111–12; early statistics field used in, 120; East India Company (British), 97–101, 109; GDP, 235–36n58; Health and Safety Executive, 66; historical colonialism and exploration by, 95–96; Opium Wars, 109; privacy laws in, 259n134; privately acquired data versus census in, 123 United States: versus China’s e-commerce market, 56; data collection and social quantification sector, 52–53; datafication of justice system/law enforcement in, 145; Department of Health and Human Services, 173; Federal Bureau of Investigation, 13; Federal Trade Commission, 11, 174; First Amendment, 179; Fourth Amendment, 178–79; on free trade, 105; GDP, 235–36n58; and geopolitical competition with China, xx; and Global North as gatekeeper of data, 103–4; internet ownership in, 20–21; internet traffic flow through, 103; on privacy, 177–79, 259n134; Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation, 52; slavery in, 73; underpaid labor in, 60–63 University of Michigan, 143 “The Untimely Mammet of Verona” (Harris), 244n89 UPS, 65 Upwork, 64–65 Van Alsenoy, Brendan, 93 Verizon Wireless, 9, 15 Vertesi, Janet, 194, 198–201 VitalityDrive (Discovery), 135 Vkontakte, 55 voice, threat to, 148, 251n190 voice picking (voice-directed order picking), 64 Volkswagen, 54 wages-for-housework argument, 230n124 Wallerstein, Immanuel, 39, 58 Wallet (Apple), 10 Walmart, 54, 55, 151, 236n58 Walton, Clifford Stevens, 243n86 Warren, Samuel, 178 WaterMinder app, x, 53 wearable devices and self-tracking technologies (WSTT), 65–66 “The Wearable Future” (PricewaterhouseCoopers), 128 Weber, Max, 18, 119 Weber, Steven, 104 WeChat (Tencent), 56 “wellness” programs, 65 Weyl, Glen, 229–30n123 “What Privacy Is For” (Cohen), 229n106 WhatsApp, 10–11 Williams, Eric, 222n24 Windows (Microsoft), 49 Winner, Langdon, 20 Wood, Allen, 153, 154 workplace surveillance, 13, 63–66, 153–54, 225n37 World Economic Forum, 89, 138–39, 178 Wylie, Christopher, 3 Yahoo!

The Smartphone Society

by

Nicole Aschoff

By the nineteenth century the long struggle to keep women inside the home seemed successful, and the image of the “natural” role for women, the content, happy mother ruling over her domestic environs, was complete.82 (It was never entirely successful because poor women always found a way to engage in paid work outside the home in order to feed their families.) This image, however, papered over a simmering discontent that erupted in waves of feminist uprising. In the 1970s women took to the streets demanding an end to patriarchy. They formed a campaign provocatively called Wages for Housework that demanded recognition for all the essential labor they performed for no pay. The struggle is ongoing, but as women have entered the waged workforce en masse over the past four decades, norms have slowly shifted. No longer do women expect to get married and remain at home; more important, no longer do men and society at large expect women to be saddled with providing all of the labor necessary for the reproduction of the work force.

…

See surveillance Square, 148 stalkerware apps, 25 Standing Rock, 103–4, 110 start-ups, 120–21 status-consciousness, 62 Sterling, Alton, 20 stewardship, 56–57 stimulation, digital, 66 stingrays, 96 Stoppelman, Jeremy, 43–44 Stop the Killing, 20 storytelling, 115–16, 120 subcontracting, multitier, 31 Substitute Phone, 8 Sullivan, Andrew, 132 Sunrise Movement, 103–4, 152, 179n22 “superstar firms,” 42–43 surveillance: big data and, 84; by government, 81, 137–38, 144, 148–49; by law enforcement, 96–97, 137–38, 176n28; by Uber, 127 surveillance capitalism, 8 sustainability, 151–52, 154–55 SVR (Silicon Valley Rising), 147 Syrian war, 90 Tahrir Square, 92 task app, mobile, 32 “tasker,” 30 TaskRabbit, 30 tax evasion by titans, 49–50 taxi drivers, 146, 178–79n5 Tea Party, 105 technological determinism, 12, 131–32, 140–41 “technology shabbats,” 133 technophilanthropy, 56–57 tech refuseniks, 67 tech start-ups, 120–21 Tech Workers Coalition, 148 teenagers, sexting by, 25–27, 35 telemedicine, 10 television, 11–12 temp workers, 31–32 Tencent, 4, 42 terrorists, 95 tether, smartphones as new, 3–7 texting, 5, 6 Thatcher, Margaret, 118 Thiel, Peter, 45, 81, 124 Thoreau, Henry David, 133 TikTok, 95 “time bind,” 30 time-tracking tools, 69 Tinder, 23–24, 25, 63 Tin Dog, 23 titans of cyberspace, 37–57; and antitrust investigations, 52–53; emerging criticisms of, 45–50; and fake news, 50–51; funding by, 55; lobbying by, 55–56; old titans vs., 37–38; and personalization, 53; philanthropy by, 56–57; power of, 39–40, 54–57; rise of, 38–45; and search algorithms, 51–52 Tometi, Opal, 101–2 tracking: government, 94–95; and privacy, 70–71, 81; of workers, 32–33 transcendentalists, 133 Transdr, 23 transhumanism, 123 translation, 10 Trump, Donald: election of, 13; and fake news, 50; inauguration of, 107; and North Dakota pipeline, 110; small donors to, 105; tweets by, 87–88, 92–93, 175n14 trust, 8 truth, 8 Twitch, 41 Twitter: addiction to, 69; content on, 60; microcelebrities on, 60; as news source, 50; as new titan, 42, 45; sharing on, 84; time spent on, 60; use by politicians of, 87–88, 92–93 230 Fifth, 62 Uber: app jobs at, 30–33, 153; data collection by, 84; and new capitalism, 119, 126–27; as new titan, 42; vs. taxi drivers, 146, 178–79n5 Uber-X, 33 Ukraine, 95 union(s), 147, 154 Union Pacific Railroad, 80 United Kingdom, 32–33 United We Dream, 104 unjust relationships, 137–38, 152–54 unpaid labor, 73–79, 84–85, 153 Upworthy, 53 urban poor, access to high-speed internet by, 29 USAID, 95 US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), 21, 148 Utah Data Center, 81 Utopia, 124–25, 132 Vanderbilt, Cornelius, 39, 44, 54 venture capital firms, 121 Verily, 41 Verizon, 42, 71 Vestager, Margrethe, 52, 150 Vice Media, 106 videos, 5 Vietnam, 95 virality in politics, 81 virtual signaling, 109, 111 Vonnegut, Kurt, 129–30 voter outreach, 89 Wages for Housework, 85 walking lanes for phone users, 3 Walmart, 33 warehouse workers, 31–32, 33, 35, 46 Warren, Elizabeth, 45 Waymo, 41 Way of the Future, 123 wealth hierarchies, 28–29, 35 WeChat app, 4 Weinstein, Harvey, 108 Weyl, E. Glen, 135 “whatever/whenever communication,” 6 #WhatIKnow, 108 WhatsApp: data collection from, 72; Facebook takeover of, 150; and new titans, 39, 41; time spent on, 60; value of, 74 white supremacy, 35, 105–7 Whole Foods, 41 WikiLeaks, 81 Wilson, Daniel J., 84 Wilson, Darren, 89 Winfrey, Oprah, 91 Wing, 41 Women’s March, 107 women’s work, 75, 84–85 work: organization of, 144; smartphone use at, 5 “workampers,” 31–32 working-class communities, effect of high-tech company location in, 48–49 Working Washington, 146 workplace, “fissuring” of, 31 World Wide Web, 40 World Wildlife Fund, 157 Xi Jinping, 95 Xu, Tony, 146–47 Yahoo, 81, 147 Yellowhammer, Anna Lee Rain, 104 Yelp, 43–44 YouTube: addiction to, 69; data collection from, 81; microcelebrities on, 60; as news source, 50; recommender algorithm of, 67; as tech titan, 39, 41, 47; time spent on, 60 Zappos, 41 Zimmerman, George, 100 Zoe, 23 Zuckerberg, Mark, 38, 39, 54, 56, 124, 172n46 Zucotti Park, 102–3 ZunZuneo, 95 BEACON PRESS Boston, Massachusetts www.beacon.org Beacon Press books are published under the auspices of the Unitarian Universalist Association of Congregations

The Road to Somewhere: The Populist Revolt and the Future of Politics

by

David Goodhart

Published 7 Jan 2017

Whereas the interwar women’s movement had seen men and women as different and had pressed for the greater feminisation of society, the postwar movement—the so-called second wave—was uninterested in or even hostile to family life, saw men and women as not only equal but the same and saw equality in the public sphere as the main marker of progress. (The 1970s wages for housework movement was an exception.) It is technology and economics as much as gender politics that have driven many of these changes to the most intimate relationships in British society. Thanks to the pill women have had more control over their fertility and families are smaller while the decline of heavy manual work and the growth of white collar and part-time jobs that value women’s ‘soft skills’ have also made possible a big expansion of female self-sufficiency.

…

.: product lines of, 86 Appiah, Kwame Anthony: 117 assortative mating: 188 Aston University: 164 austerity: 98, 200 Australia: 4, 160 Austria: 56, 69–70 authoritarianism: 8, 12, 30, 33, 44, 57; concept of, 57; hard, 45 Baggini, Julian: observations of British class system, 59 Bangladesh: 130 Bank of England: personnel of, 86 Bartels, Larry: Democracy for Realists, 61 Bartlett, Jamie: Radicals, 64 Basel Accords: 85 BASF: 176 Bayer: 176 Belgium: 73, 75, 101; Brussels, 53, 89, 93, 95, 98 Berlusconi, Silvio: 65 birther movement: 68 Bischof, Bob: head of German-British Forum, 174 Blair, Tony: 10, 76, 159, 189; administration of, 218; foreign policy of, 96; speeches of, 3, 7, 49; support for Bulgarian and Romanian EU accession, 26; unravelling of legacy, 221 Bloomsbury Group: 34 Bogdanor, Vernon: concept of ‘exam-passing classes’, 3 Boyle, Danny: Summer Olympics opening ceremony (2012), 111, 222 Branson, Richard: 11 Brexit (EU Referendum)(2016): 1–2, 19, 27, 81, 89, 93, 99–100, 125, 233; negotiations, 103; polling prior to voting, 30, 64; Remainers, 2, 19–20, 52–3, 132; sociological implications of, 4–7, 13, 53–4, 118, 126, 167–8, 225; Stronger In campaign, 61; Vote Leave campaign, 42, 53, 72, 91, 132; voting pattern in, 7–9, 19–20, 23, 26, 36, 52, 55–6, 60, 71, 74, 215, 218 British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC): 112, 145; Newsnight, 60; personnel of, 15; Radio 4, 31, 227; Today, 60 British Empire: 107 British National Party: European election performance of (2009), 119; supporters of, 38 British Future: 19 British Private Equity and Venture Capital Association: personnel of, 135 British Social Attitudes (BSA) surveys: 153; authoritarian-libertarian scale, 44–5; findings of, 38–9, 44, 106–7, 120, 202, 206–7, 218; immigration survey (2013), 44; personnel of, 218–19 British Values Survey: establishment of (1973), 43; groups in, 43 Brooks, Greg: Sheffield report, 155 Brown, Belinda: 205, 207–8 Brown, Gordon: 106; abolition of Married Couples Allowance, 204; budget of (2006), 147–8; political rhetoric of, 16–17 Brummer, Alex: Britain for Sale, 173 Bulgaria: 26; accession to EU, 225 (2007); migrants from, 126; population levels of, 102 Burgess, Simon: 131 Burggraf, Shirley: Feminine Economy and Economic Man, The, 194 Cahn, Andrew: 98 Callaghan, Jim: Ruskin College speech (1976), 154 Callan, Eamonn: 191 Callan, Samantha: 202, 212 Cambridge University: 35, 179, 186; faculty of, 37; students of, 158–9 Cameron, David: 71, 103, 179, 183, 189; administration of, 226; cabinet of, 187 Canada: 160; mass immigration in, 119 capital: 9, 100; cultural, 190; human, 34; liberalisation of controls, 97; social, 110 capitalism: 7, 11; organised, 159 Care (Christian Action Research & Education): 203 Carswell, Douglas: 13 Case, Anne: 67 Casey, Louise: review of opportunity and integration, 129 Catholicism: 15, 213; original sin, 57 Cautres, Bruno: 72 Center for Humans and Nature: 30 Centre for Social Justice: 206; personnel of, 202 chauvinism: 33; decline in prevalence of, 39; violent, 106 China, People’s Republic of: 10, 95, 104, 160; accession to WTO (2001), 88; manufacturing sector of, 86; steel industry of, 87 Chirac, Jacques: electoral victory of (2002), 49 Christianity: 33, 69, 83, 156 citizenship: 68, 121–2; democratic, 7; global, 114; legislation, 103; national, 5; relationship with migration, 126; shared, 113; temporary, 126 Clarke, Charles: British Home Secretary, 84 Clarke, Ken: education reforms of, 158–9 Clegg, Nick: 11, 13, 189 Cliffe, Jeremy: 10–11; ‘Britain’s Cosmopolitan Future’ 216; observations of social conservatism, 217 Clinton, Bill: 29, 76; administration of, 218 Clinton, Hillary: electoral defeat of (2016), 67–8 Coalition Government (UK) (2010–16): 13, 54, 226; cabinet members of, 16; immigration policies of, 124–5 Cold War: end of, 83, 92, 95, 98 Collier, Paul: 110; view of potential reform of UNHCR, 84 colonialism: 87; European, 105 communism: 58 Communist Party of France: 72 Confederation of British Industry (CBI): 164 confirmation bias: concept of, 30 Conservative Party (Tories)(UK): 19, 207; dismantling of apprenticeship system by, 157; ideology of, 76, 196; members of, 31, 164, 187; Party Conference (2016), 226; Red Toryism, 63; supporters of, 24, 35, 77, 143, 216–17 conservatism: 4, 9; cultural, 58; social, 217; Somewhere, 7–8; working-class, 8 Corbyn, Jeremy: elected as leader of Labour Party, 20, 53, 59, 75, 78 Cowley, Philip: 35 Crosland, Tony: Secretary of Education, 36; two-tier higher education system proposed by, 158 Crossrail 2: 228; spending on, 143 Czech Republic: 69, 73 D66: supporters of, 76 Dade, Pat: 43–4, 219; role in establishment of British Values Survey, 43, 218–19 Daily Mail: 227; reader base of, 4 Danish Peoples’ Party: 55, 69–70, 73; ideology of, 73 Darwin, Charles: 28 death penalty: 44; support for, 39, 216–17 Deaton, Angus: 67 deference, end of: 63 Delors, Jacques: 96, 103–4; President of European Commission, 94 Democratic Party: ideology of, 62, 65; shortcomings of engagement strategies of, 66–7 Demos: 137 Dench, Geoff: 207; concept of ‘quality with pluralism’, 214; Transforming Men, 209 Denmark: 69, 71, 99; education levels in, 156 Diana, Princess of Wales: death of (1997), 107 double liberalism: 1, 11, 63 Duffy, Gillian: 124 Dyson: 173; Dyson effect, 173 Economist: 10, 210, 216 Eden, Anthony: administration of, 187 Eichengreen, Barry: 91 Elias, Norbert: 119 Employer Skills Survey: 163 Engineering Employers Federation: 166 Englishness: 111 Erdogan, Recep Tayyip: 218 Essex Man/Woman: 186 Estonia: population levels of, 102 Eton College: 179, 187 Euro (currency): 100–1; accession of countries to, 98–9 European Commission: 26, 97 European Convention on Human Rights: 83–4 European Court of Justice (ECJ): 103 European Economic Community (EEC): 92; British accession to (1973), 93; Treaty of Rome (1957), 101 European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM): 97–8 European Parliament: elections (2009), 71–2; elections (2014), 72 European Union (EU): 10, 25, 53, 76, 89, 92–4, 99–100, 120, 124, 160, 215, 221–2, 229, 233; Amsterdam Treaty (1997), 94; Common Agricultural Policy, 92, 96; establishment of (1957), 91–2; freedom of movement principles, 100–1, 163–4; Humanitarian Protection Directive (2004), 83; integration, 50, 98–9, 173; Lisbon Treaty (2009), 94; Maastricht Treaty (1992), 94, 96, 103; members states of, 16, 31, 55, 71, 216; personnel of, 128; Schengen Agreement (1985), 94–5, 99, 117; Single European Act (1986), 94; Treaty of Nice (2000), 94 Euroscepticism: 69 Eurozone Crisis (2008–): 92, 99 Evening Standard: 143–5 Facebook: 86 family culture: 196–7; childcare, 202–3; cohabitation, 196, 211; divorce figures, 196–7; gender roles, 206–13; legislation impacting, 195–6; lone parents, 196; married couples tax allowance, 225; relationship with state intrusion, 200–2; tax burdens, 203–4; tax credit systems, 202, 204–5, 225 Farage, Nigel: 11; leader of UKIP, 72; political rhetoric of, 20 Fawcett Society: surveys conducted by, 195–6 federalism: 69 feminism: 185, 199, 205; gender pay gap, 198–9; orthodox, 194 Fidesz: 69, 71, 73 Fillon, François: 73 Financial Times: 91, 108, 115, 138, 145, 147 Finkelstein, Daniel: 34 Five Star Movement: 53, 55, 64, 70, 73 Florida, Richard: concept of ‘Creative Class’, 136 Foges, Clare: 183 food sector: 17, 102, 125, 126 Ford, Robert: 35, 150 foreign ownership: 172–74, 230 Fortuyn, Pim: assassination of (2002), 50, 69 France: 69, 75, 94–6, 101, 173; agricultural sector of, 96; compulsory insurance system of, 222; Paris, 104, 143; high-skill/low-skill job disappearance in, 151; Revolution (1789–99), 106 Frank, Thomas: concept of ‘liberalism of the rich’, 62 Franzen, Jonathan: 110 free trade agreements: opposition to, 62 Freedom Party: 69; electoral defeat of (2016), 70; ideology of, 73; supporters of, 70 French Colonial Empire (1534–1980): 107 Friedman, Sam: ‘Introducing the Class Ceiling: Social Mobility and Britain’s Elite Occupations’, 187 Friedman, Thomas: World is Flat, The, 85 Front National (FN): 53, 69, 72–3; European electoral performance of (2014), 72; founding of (1973), 72; supporters of, 72 Gallup: polls conducted by, 65 Ganesh, Janan: 115, 145 gay marriage: 5, 76; opposition to, 46–7; support for, 26, 220 General Electric Company (GEC) plc: 172, 175 German-British Forum: members of, 174 Germany: 70, 73, 86, 94, 96, 100–1, 173–4, 209; automobile industry of, 96; chemical industry of, 176; compulsory insurance system of, 222; education sector of, 166; high-skill/low-skill job disappearance in, 151; labour market of, 147; Leipzig, 58; Ludwigshafen, 176; Reunification (1990), 96, 147, 176; Ruhr, 176–7 Ghemawat, Prof Pankaj: 85–6 Gilens, Martin: study of American public policy and public preferences, 61–2 Glasman, Maurice: 227 Global Financial Crisis (2007–9): 56, 169–70, 177; Credit Crunch (2007–8), 98, 177 Global Villagers: 31–2, 44–5, 160, 226; characteristics of, 46; political representation of, 75; political views of, 109, 112 globalisation: 9–10, 50–2, 81–2, 85, 87–8, 90–1, 105–6, 148; economic, 9; global trade development, 86–7; growth of, 85–6; hyperglobalisation, 88–9; relationship with nation states, 85–6; sane, 90 Golden Dawn: 74; growth of, 105 Goldman Sachs: personnel of, 31 Goldthorpe, John: 184–5, 189–90 Goodhart, David: 12 Goodwin, Fred: 168 Goodwin, Matthew: 150 Gordon, Ian: 137–8, 140 Gould, Philip: 220 Gove, Michael: 64, 91 great liberalisation: 39–40, 47; effect of, 40 Greater London Authority (GLA): 143 Greece: 53, 56, 69, 74, 99, 105; Athens, 143; government of, 98 Green, Francis: 163 Green Party (UK): supporters of, 38 Group of Twenty (G20): 89 Guardian: 14, 210 Habsburg Empire (Austro-Hungarian Empire): collapse of (1918), 107 Haidt, Jonathan: 11, 30, 33, 133; Righteous Mind, The, 28–9 Hakim, Catharine: 205 Hall, Stuart: 14–15 Hames, Tim: 135–6 Hampstead/Hartlepool alliance: 75 Hanson Trust: subsidiaries of, 175 Hard Authoritarian: 43–7, 51, 119, 220; characteristics of, 24–5; political views of, 109 Harris, Gareth: 137; ‘Changing Places’, 137 Harvard University: faculty of, 57 Heath, Edward: foreign policy of, 96 Higgins, Les: role in establishment of British Values Survey, 43 High Speed 2 (HS2): 228 High Speed 3 (HS3): aims of, 151, 228 Hitler, Adolf: 94 Hoescht: 176 Hofstadter, Richard: ‘Everyone is Talking About Populism, But No One Can Define It’ (1967), 54 Holmes, Chris: 151 homophobia: observations in BSA surveys, 39; societal views of, 39–40, 216 Honig, Bonnie: concept of ‘objects of public love’, 111 Huguenots: 121 Huhne, Chris: 16, 32 human rights: 5, 10, 55, 113; courts, 113; legislation, 5, 83–4, 109, 112; rhetoric, 112–13 Hungary: 53, 64, 69, 71, 73–4, 99, 218; Budapest, 218 Ignatieff, Michael: leader of Liberal Party (Canada), 13 Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI): 172, 174–5; personnel of, 169; subsidiaries of, 175 Inbetweeners: 4, 25, 46, 109; political views of, 109 India: 104 Inglehart, Ronald: theories of value change, 27 Insider Nation: concept of, 61, 64; evidence of, 61–2 Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS): 201; findings of, 211–12 International Monetary Fund (IMF): 86–7, 102 interracial marriage: societal views of, 40 India: 10, 160 Ipsos MORI: polls conducted by, 42, 122 Iraq: 84; Operation Iraqi Freedom (2003–11), 82 Islam: 50; Ahmadiyya, 84; conservative, 131; Halal, 68; hostility to, 73; Qur’an, 50 Islamism: 130 Islamophobia: 130 Italy: 55, 64, 69–70, 73, 96; migrants from, 125 Jamaica: 14 Japan: 86; request for League of Nations racial equality protocol (1919), 109 Jews/Judaism: 121, 259; orthodox, 131; persecution of, 17 jingoism: 8 Jobbik: 53, 64, 74 Johnson, Boris: 145 Jones, Sir John Harvey: death of (2008), 169 Jordan, Hashemite Kingdom of: government of, 84 Jospin, Lionel: defeat in final round of French presidential elections (2002), 49 Judah, Ben: This is London: Life and Death in the World City, 145 Kaufmann, Eric: 8–9, 131, 219, 227; ‘Changing Places’, 137 Kellner, Peter: 78 King, Mervyn: Governor of Bank of England, 86 Kinnock, Neil: 98 knowledge economy: 147, 149, 154, 166, 221 Kohl, Helmut: 94 Kotleba: 74 Krastev, Ivan: 55, 65, 82–3 labour: 9, 89–90, 149; eastern European, 125–6; gender division of, 197; hourglass labour market, 150, 191; living wage, 26, 152; market, 95, 101–2, 124, 140, 147–8, 150–2, 156–7, 181, 225 Labour Party (Denmark): 77 Labour Party (Netherlands): 50; supporters of, 76 Labour Party (UK): 2, 23, 53, 57, 72, 123, 157, 159, 207; Blue Labour, 63; electoral performance of (2015), 75; European election performance (2014), 72; expansion of welfare state under, 199–200; members of, 14, 20, 36, 59, 61, 77–8, 84; Momentum, 53; New Labour, 33, 75, 107, 123, 155, 159, 167, 196, 207, 220, 226, 232; Party Conference (2005), 7; social media presence of, 79; supporters of, 17, 35, 75, 77, 143, 221; voting patterns in Brexit vote, 19 Lakner, Christoph: concept of elephant curve, 87 Lamy, Pascal: 97 Latvia: adoption of Euro, 98–9; migrants from, 25–6 Laurison, Daniel: ‘Introducing the Class Ceiling: Social Mobility and Britain’s Elite Occupations’, 187 Law and Justice Party: 69, 71, 73 Lawson, Nigel: 205 Le Pen, Jean-Marie: victory in final round of French presidential elections (2002), 49, 69 Le Pen, Marine: 53; electoral strategies of, 73 Leadbeater, Charles: 53 League of Nations: protocols of, 109 left-behinders: 20 Lega Nord: 69 Levin, Yuval: Fractured Republic, The, 232 liberal democracy: 2, 31, 55 Liberal Democrats: 23, 53–4; members of, 16; supporters of, 38, 78 Liberal Party (Canada): members of, 13 liberalism: 4–5, 12–13, 29–31, 55, 76, 119, 127–8, 199, 233; Anywhere, 27–8; baby boomer, 6; double, 1, 63; economic, 11; graduate, 216–17; meritocratic, 34; metropolitan, 216; orthodox, 13–14; Pioneer, 44; social, 4, 11 libertarianism: 8, 11, 22, 39, 44 Libya: 84; Civil War (2011), 225 Lilla, Mark: 35 Lind, Michael: 105, 135 Livingstone, Ken: 136 Lloyd, John: 56 London School of Economics (LSE): 54, 137–8, 140, 183 Low Pay Commission: findings of, 170 Lucas Industries plc: 172 male breadwinner: 149, 194, 195, 198, 206, 207 Manchester University: faculty of, 131 Mandelson, Peter: British Home Secretary, 61; family of, 61 Mandler, Peter: 135 Marr, Andrew: 53, 181 Marshall Plan (1948): 92 mass immigration: 14, 55, 104–5, 118–19, 121–4, 126–7, 140, 228–9; accompanied infrastructure development, 137–9; brain-drain issue, 102; debate of issue, 81–2; freedom of movement debates, 100–3; housing levels issue, 138–9; impact on wages, 152; integration, 129–32, 140–2; non-EU, 124–5; opposition to, 16–17, 120, 220 May, Theresa: 63, 179, 183, 198–9; administration of, 173, 176, 187, 191, 230; British Home Secretary, 124–5; ‘Citizens of Nowhere’ speech (2016), 31; political rhetoric of, 15, 31, 226 McCain, John: electoral defeat of (2008), 68 meritocracy: 152, 179–80, 190; critiques of, 180–1; perceptions of, 182–3 Merkel, Angela: reaction to refugee crisis (2015), 71 Mexico: borders of, 21 migration flows: global rates, 82, 87; non-refugee, 82 Milanovic, Branko: 126; concept of elephant curve, 87 Miliband, Ed: 78, 189 Mill, John Stuart: ‘harm principle’ of, 11–12 Millennium Cohort Study: 159 Miller, David: concept of ‘weak cosmopolitanism’, 109 Mills, Colin: 185 Mitterand, François: 94, 97 mobility: 8, 11, 20, 23, 36, 37, 38, 153, 167, 219; capital: 86, 88; geographical, 4, 6; social, 6, 33, 58, 152, 168, 179, 180, 182, 183–191, 213, 215, 220, 226, 231 Moderate Party: members of, 70 Monnet, Jean: 94–5, 97, 103–4 Morgan Stanley: 171 Mudde, Cas: observations of populism, 57 multiculturalism: 14, 50, 141–2; conceptualisation of, 106; laissez-faire, 132 narodniki: 54 national identity: 14, 38, 41, 111–12; conceptualisations of, 45; indifference to, 41, 46, 106, 114; polling on, 41 nationalism: 38, 46–7, 105; chauvinistic, 107, 120; civic, 23, 53; extreme, 104; moderate, 228; modern, 112; post-, 8, 105–6, 112; Scottish, 221 nativism: 57 Neave, Guy: 36 net migration: 126; White British, 136 Netherlands: 13–14, 50, 69, 73, 75, 99–100; Amsterdam, 49, 51; immigrant/minority population of, 50–1; Moroccan population of, 50–1 Netmums: surveys conducted by, 205–6 New Culture Forum: members of, 144 New Jerusalem: 105 New Society/Opinion Research Centre: polling conducted by, 33 New Zealand: 160 Nextdoor: 114 non-governmental organizations (NGOs): 21; refugee, 82 Norris, Pippa: 57 North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA): 91; opposition to, 62 North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO): 85, 92; personnel of, 84 Norway: 69 Nuttall, Paul: leader of UKIP, 72; Obama, Barack: 67; approval ratings of, 60; electoral victory of (2012), 68; healthcare policies of, 22–3; target of birther movement, 68 O’Donnell, Gus: background of, 15–16; British Cabinet Secretary, 15 O’Leary, Duncan: 232 Open University: Centre for Research on Socio-Cultural Change (CRESC), 172–3 Operation Iraqi Freedom (2003–11): political impact of, 56 Orbán, Victor: 69, 218 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD): 201, 204; report on education levels (2016), 155–6; start-ups ranking, 173 Orwell, George: Nineteen Eighty-Four, 108–9 Osborne, George: 189; economic policies of, 4, 226 Oswald, Andrew: 171 Ottoman Empire: collapse of (1923), 107 outsider nation: concept of, 61, 64 Owen, David: 99 Oxford University: 15, 35, 179, 186; Centre on Skills, Knowledge and Organisational Performance, 151; faculty of, 31, 151; Nuffield College, 32 Pakistan: persecution of Ahmadiyya Muslims in, 84 Parris, Matthew: 115 Parsons, Talcott: concept of ‘achieved’ identities, 115 Party of Freedom (PVV): 69; ideology of, 73; supporters of, 50, 76 Paxman, Jeremy: 42 Pearson: ownership of Higher National Certificates (HNCs)/Higher National Diplomas (HNDs), 157 Pegida: ideology of, 73 Pessoa, Joao Paulo: 88 Phalange: 74 Phillips, Trevor: 133 Pioneers: characteristics of, 43–4 Plaid Cymru: supporters of, 38 Podemos: 53, 64 Poland: 56, 69, 73; migrants from, 25–6, 121 Policy Exchange: ‘Bittersweet Success’, 188 political elites: media representation of, 63–4 populism: 1, 5, 13–14, 49–52, 55–6, 60, 64, 67, 69–74, 81; American, 54, 65; British, 63; decent, 6, 55, 71, 73, 219–20, 222, 227, 233; definitions of, 54; European, 49, 53, 65, 68–9, 74; left-wing, 54, 56; opposition to, 74; right-wing, 33, 51, 54 Populists: 54 Portillo, Michael: 31 Portugal: migrants from, 121, 125 post-industrialism: 6 post-nationalism: 105 poverty: 83, 168; child, 183–4, 200, 204; extreme, 87; reduction of, 78, 200; wages, 231 Powell, Enoch: ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech (1968), 127 Professionalisation of politics: 59 Progress Party: 69 progressive individualism: 5 Progressive Party: founding of (1912), 54 proportional representation: support for, 228 Prospect: 14, 91, 136 Prospectors: characteristics of, 43 Protestantism: 8, 213 Putin, Vladimir: 218 Putnam, Robert: 22; theory of social capital, 110 racism: 32, 73–4, 134; observations in BSA surveys, 39; societal views of, 39; violent, 127 Rashid, Sammy: Sheffield report, 155 Reagan, Ronald: 58, 63; approval ratings of, 60 Recchi, Ettore: 104 Refugee Crisis (2015–): 83–4; charitable efforts targeting, 21–2; government funds provided to aid, 83; political reactions to, 71 Relationships Foundation: 202 Republic of Ireland: 99; high-skill/low-skill job disappearance in, 151; property bubble in, 98 Republican Party: ideology of, 62, 65; members of, 68 Resolution Foundation: 87–8; concept of ‘squeezed middle’, 168–9; reports of, 171 Ricardo, David: trade theory of, 101 Robinson, Eric: 36 Rodrik, Dani: 82, 89; concept of ‘hyperglobalisation’, 88; theory of ‘sane globalisation’, 90 Romania: 26; accession to EU, 225 (2007); migrants from, 102, 126 Romney, Mitt: electoral defeat of (2012), 68 Roosevelt, Theodore: leader of Progressive Party, 54 Rousseau, Jean-Jacques: 156 Rowthorn, Bob: 149 Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS): personnel of, 168 Royal College of Nursing: 140 Rudd, Amber: foreign worker list conflict (2016), 17 Ruhs, Martin: 126 Russell Group: 55; culture of, 37; student demographics of, 130–1, 191 Russian Federation: 2, 92; Moscow, 218; St Petersburg, 218 Rwanda: Genocide (1994), 82 Saffy factor: concept of, 199, 221–2 Scheffer, Paul: 85; ‘Multicultural Tragedy, The’ (2000), 49–50 Schumann, Robert: 94 Sciences Po: personnel of, 104 Scottish National Party (SNP): 1, 23, 54, 112; electoral performance of (2015), 75; ideology of, 53 Second World War (1939–45): 105, 194; Holocaust, 109 Security and identity issues: 41, 78, 81 Settlers: characteristics of, 43 Sikhism: 131 Singapore: 101, 128; education levels in, 156 Slovakia: 69, 73–4 Slovenia: adoption of Euro, 98–9 Smer: 69, 73 Smith, Zadie: 141–2 Social Democratic Party: supporters of, 75–6 social mobility: 6, 33, 58, 179–80, 183, 187, 189–91, 220; absolute mobility, 184, 188; relative mobility, 184; slow, 168; upward, 152 Social Mobility Commission: 161, 179–80 socialism: 49, 72, 183, 190 Somewheres: 3–5, 12–13, 17–18, 20, 41–3, 45, 115, 177, 180, 191, 214, 223, 228; characteristics of, 5–6, 2, 32; conflict with Anywheres, 23, 79, 81, 193, 215; conservatism, 7–8; employment of, 11; European, 103; immigration of, 106; moral institutions, 223–4; political representation/voting patterns of, 13–14, 24–6, 36, 53–5, 77–9, 124, 227; political views of, 71, 76, 109, 112, 119, 199, 218, 224–6, 232; potential coalition with Anywheres, 220, 222, 225–6, 233; view of migrant integration, 134 Sorrell, Martin: 31 Soskice, David: 159 South Korea: 86 Soviet Union (USSR): 92, 188; collapse of (1991), 82, 107 Sowell, Thomas: 30; A Conflict of Visions, 29 Spain: 53, 56, 64, 74; government of, 98; migrants from, 125; property bubble in, 98 Steinem, Gloria: 198 Stenner, Karen: 30, 44, 122, 133, 227; Authoritarian Dynamic, The, 30–1 Stephens, Philip: 108 Sun, The: 227 Sutherland, Peter: 31–2 Sutton Trust: end of mobility thesis, 183–5 Swaziland: 135 Sweden: 56, 70, 100; general elections (2014), 70; Stockholm, 143; taxation system of, 222 Sweden Democrats: 70; electoral performance of (2014), 70; ideology of, 73 Switzerland: 37 Syria: Civil War (2009–), 82, 84 Syriza: 53, 69 Taiwan: 86 Teeside University: 164 terrorism: jihadi, 71, 74, 129 Thatcher, Margaret: 58, 63, 95, 189, 205; administration of, 169; economic policies of, 176 Third Reich (1933–45): 104; persecution of Jews in, 17 Times Education Supplement: 37 Timmermans, Frans: EU Commissioner, 128 Thompson, Mark: Director-General of BBC, 15 trade theory: principles of, 101 Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP): 89; support for, 225 Trump, Donald: 50, 62, 74, 85; electoral victory of (2016), 1–3, 5–7, 13, 27, 30, 64–8, 81, 232; political rhetoric of, 14, 22–3, 51, 54, 66–7; supporters of, 56, 67 Tube Investments (TI): 172 Turkey: 218 Twitter: use for political activism, 79 Uber: 140 UK Independence Party (UKIP): 53, 55, 63–4, 69, 71–3, 228; electoral performance of (2015), 75; European election performance (2009), 71–2; members of, 13; origins of, 72; supporters of, 24, 35, 38, 72, 75, 143, 168, 216, 222 ultimatum game: 52 Understanding Society: surveys conducted by, 37–8, 202 unemployment: 101–2; gender divide of, 208–9; not in employment, education or training (Neets), 151–2, 190; youth, 139, 151–2, 166 Unilever: 175 United Kingdom (UK): 1–3, 8, 11–12, 21, 27–8, 31, 33, 41, 44, 59–60, 69, 73, 75, 81, 83, 91, 111–12, 147, 165, 173, 180, 193–5, 199, 204, 217, 227; Aberdeen, 136; accession to EEC (1973), 93; Adult Skills budget of, 161, 225; apprenticeship system of, 154, 157, 162–3, 166; Birmingham, 7, 123, 166; Boston, 121; Bradford, 133, 136; Bristol, 136; British Indian population of, 77; Burnley, 151; Cambridge, 136; City of London, 95, 106, 174; class system in, 58–9, 75, 123, 135–6, 149–52, 172, 182–3, 186, 195; Dagenham, 136; Department for Education, 206; Department for International Development (DfID), 224; Divorce Law Reform Act (1969), 196; economy of, 152, 170; Edinburgh, 54, 136; education sector of, 35, 147, 154–8; ethnic Chinese population of, 77; EU citizens in, 101; Finance Act (2014), 211; Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO), 224; Glasgow, 136; high-skill/low-skill job disappearance in, 150–1; higher education sector of, 35–7, 47, 159–62, 164–7, 179, 208, 230–1; Home Office, 17; House of Commons, 162; general election in (2015), 60; House of Lords, 31; Human Rights Act, 123, 225; income inequality levels in, 169–70, 172, 177, 184–5; labour market of, 16, 26, 124, 140–1, 148, 150–1, 152, 225; Leicester, 133; Leeds, 161; London, 3–4, 7, 10–11, 18–19, 24, 26, 34, 37, 59, 79, 101, 114–15, 119, 123, 131, 133–45, 151, 168, 216, 218, 226, 228, 232–3; Manchester, 123, 136, 151, 161, 228; manufacturing sector of, 17, 88; mass immigration in, 122–4, 126–7, 228–9; Muslim immigration in, 41–2, 44; Muslim population of, 127, 130; National Health Service (NHS), 72, 91, 111, 120, 140, 144, 200–1, 229; National Insurance system of, 204; Newcastle, 131, 136, 161; Northern Ireland, 38; Office for Fair Access, 180; Office for Standards in Education, Children’s Services and Skills (Ofsted), 155; Office of National Statistics (ONS), 138, 144–5; Oldham, 133; Olympic Games (2012), 111, 143, 222; Oxford, 136; Parliamentary expenses scandal (2009), 56, 168; Plymouth, 131; public sector employment in, 171, 208–9, 229–30; regional identities in, 3–4, 186; Rochdale, 124; Scotland, 110, 138; Scottish independence referendum (2014), 53, 110; self-employment levels in, 171; Sheffield, 161; Slough, 131, 133; social mobility rate in, 58, 184–5, 187; start-ups in, 173–4; Stoke, 121; Sunderland, 52, 172; Supreme Court, 66; taxation system of, 222; Treasury, 16; UK Border Agency, 108; vocational education in, 163; voting patterns for Brexit vote, 7–9, 19–20, 23, 26, 36, 52; wage levels in, 168; Wales, 138; welfare state in, 199–203, 223–4, 231–2; Westminster, 54, 58, 60; youth unemployment in, 151–2 United Nations (UN): 102, 198; Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), 10; Declaration of Human Rights (1948), 109; Geneva Convention (1951), 82–4; High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR), 82, 84; Security Council, 99 United States of America (USA): 1–2, 6–7, 22–3, 36–7, 51, 57, 60, 74, 86, 89, 94, 128, 168, 193, 208, 227; 9/11 Attacks, 130; Agency for International Development (USAID), 224; Asian population of, 68; borders of, 21; Chinese Exclusion Act (1882), 54; class identity in, 65–6; Congress, 67; Constitution of, 57; education system of, 166; higher education sector of, 167; Hispanic population of, 67–8, 85; House of Representatives, 67; immigration debate in, 67–8; Ivy League, 36, 61; New York, 135; political divisions in, 65; Senate, 67 University College London (UCL): Imagining the Future City: London 2061, 137, 139 University of California: 165 University of Kent: 36 University of Sussex: 36 University of Warwick: 36; faculty of, 171 Vietnam War (1955–75): 29 Visegrad Group: 69, 73, 99 Vlaams Belang: ideology of, 73 wages for housework: 194 Walzer, Michael: 117–18 War on Drugs: 62 WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialised, Rich and Democratic): 27 Welzel, Christian: Freedom Rising, 27 Westminster University: 165 white flight: 129, 134, 136 white identity politics: 9, 67 white supremacy: 8, 68, 73–4 Whittle, Peter: 144 Wilders, Geert: 50, 76 Willetts, David: 164, 185 Wilson, Harold: electoral victory of (1964), 150 Wolf, Prof Alison: 162, 164–5; XX Factor, The, 189, 198 working class: 2–4, 6, 51–2, 59, 61, 65; conservatism, 8 political representation/views of, 8, 52, 58, 63, 70, 72; progressives, 78–9; voting patterns of, 15, 52, 75–6; white, 19, 68 World Bank: 84 World Trade Organisation (WTO): 10, 85, 89–90, 97; accession of China to (2001), 88 World Values Survey: 27 xenophobia: 2, 14, 50–1, 57, 71, 119, 121, 141, 144, 225 York, Peter: 138 York University: 36 YouGov: personnel of, 78; polls conducted by, 16–17, 42, 66, 79, 114, 132, 141 Young, Hugo: 93 Young, Michael: 119, 190; Rise of the Meritocracy, The, 180–1 Yugoslav Wars (1991–2001): 97 Yugoslavia: 97 Zeman, Milos: President of Czech Republic, 73

The Stolen Year

by

Anya Kamenetz

Published 23 Aug 2022

The force that connects us all is a constantly renewed choreography of care. Ai-Jen Poo, who devotes herself to lifting up domestic workers with the National Domestic Workers Alliance, says care is the work that makes other work possible. The feminist economist Silvia Federici, originator of “wages for housework” campaigns in the 1970s, defines care as reproductive labor. This is a pun: it’s both the labor that makes people and the kind that needs to be redone every day because it disappears without a trace—Sisyphus, doing the dishes. Joan Tronto, a political scientist, is the author of the book Caring Democracy and a major theorist of care.

…

Eventually, by 1934, a year after the New Deal began, there were “mother’s aid” laws in forty-six states, the District of Columbia, plus the territories of Alaska and Hawaii. The first government-sponsored welfare program in the United States, mothers’ pensions were a historical fork in the road. The mothers’ pension, more than a hundred years ago, actually put a dollar value on women’s care work. Wages for housework! This was considered a radical idea at the fringes of feminism in the 1970s, and fifty years later it remains radical and fringe. The public discourse framed care work as noble, even a public service. “If she has given a citizen to the nation, the nation owes something to her,” proclaimed a Mrs.

Head, Hand, Heart: Why Intelligence Is Over-Rewarded, Manual Workers Matter, and Caregivers Deserve More Respect

by

David Goodhart

Published 7 Sep 2020

The fact that it is not such a central concern seems to reinforce the analysis of Alison Wolf, Joanna Williams, and others who argue that family and gender politics have been captured by the cognitive class, professional women whose interests are not always the same as those of other women. Ever since the failure of the Wages for Housework movement in the 1970s, the main concern of women’s politics has been equality at work outside the home and, in more recent decades, above all equality with professional men in the world of careers. This goal has been substantially achieved, according to Wolf, with women, as already noted, now accounting for half of all members of the top—professional and managerial—social class in the United Kingdom, even if they are still largely absent from the very pinnacle of the professional and business tree.

…

D., Hillbilly Elegy, 190 Veblen, Thorstein, 205 veil of ignorance (Rawls), 87 Victoria, Queen of United Kingdom, 41 Vignoles, Anna, 263, 269 vocational training: academic training combined with, 99 college/university education vs., 97–98, 107 in France, 117–18 further education (FE) colleges (UK), 105–6, 108–10, 115 in Germany, 24, 35, 47, 117–19 polytechnics/“new universities” (UK), 98, 100–102, 105–8, 115, 119, 263 in the UK, 15, 40, 42, 46–47, 50, 97–98, 100–102, 105–8, 198, 265 in the US, 49, 50, 114, 115 see also apprenticeships Volkswagen Group, 192 volunteer work, 129, 239, 246, 247, 294 Vonnegut, Kurt, Bluebeard, 142 Wages for Housework movement, 229 Wales, Robin, 283–84 Walmart, x Warren, Elizabeth, 14 Watt, James, 42 WebMD network, 261 Wechsler, David, 65 Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, 65 Wessely, Simon, 221–22 WhatsApp, xiii, 290 Wille, Anchrit, Diploma Democracy (with Bovens), 95, 155–58, 169, 177–78 Willetts, David, 98, 113 The Pinch, 79–80 Williams, Joan C., White Working Class, 18 Williams, Joanna, 227–28, 229, 296 Willis Commission, 147–48 Willmott, Peter, Family and Kinship in East London (with M.

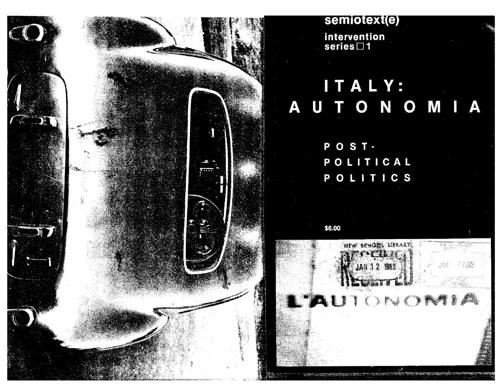

Autonomia: Post-Political Politics 2007

by

Sylvere Lotringer, Christian Marazzi

Published 2 Aug 2005

Ferruccio Gambino teaches sociology at the Institute since 1970, Maria Rosa Dalla Costa is a widely known feminist, who for years has work· ed in the "Wages For Housework" movement and is the author of many feminist texts, including The Power of Women and the Subversion of the Community. 'I can only understand this judiciary communication as an attack on feminism ... It Is the last act of a wltch·hunt launched since April 7 against the Institute where I work, as well as against many brothers and sisters, in the attempt to crlmlnalize our contribution to scientific research and the political debate. As far as I am con· cerned, It Is clear that this time the target is "Wages for Housework," for all that this strategy implies in terms of the struggles for autonomy, more money and less work, that women have made."

Having and Being Had

by

Eula Biss

Published 15 Jan 2020

Do I dare to eat a peach, he asks, after indecisions and revisions, after toast and tea, after a life measured out in coffee spoons, and after having already asked, Do I dare / Disturb the universe? Women shouldn’t have to work for nothing, I tell my sister, and neither should artists, but I feel the way some women once felt about the Wages for Housework movement—if I were paid wages for the work of making art, then everything I do would be monetized, everything I do would be subject to the logic of this economy. And if art became my job, I’m afraid that would disturb my universe. I would have nothing unaccountable left in my life, nothing worthless, except for my child.

Practical Anarchism: A Guide for Daily Life