Framing Class: Media Representations of Wealth and Poverty in America

by

Diana Elizabeth Kendall

Published 27 Jul 2005

Below the working class in the social hierarchy is the working-poor category (about 13 percent of the U.S. population). Members of the working poor live just above or below the poverty line. Typical annual household income is about $25,000. Individuals identified as the working poor often hold unskilled jobs, seasonal migrant jobs in agriculture, lower-paid factory jobs, and minimum-wage service-sector jobs (such as counter clerk in restaurants). As some people once in the unionized, blue-collar sector of the workforce have lost their jobs, they have faced increasing impoverishment. A large number of the working poor hold full-time jobs, and some hold down more than one job, but they simply cannot make ends meet.

…

However, as goods-producing jobs have decreased, union membership has dropped to a small fraction of 9781442202238.print.indb 123 2/10/11 10:46 AM 124 Chapter 5 the labor force.10 Consequently, the power of the working class to influence economic and political decisions has diminished; today, the media frequently characterize the working class as low in political participation. Some scholars believe that the working poor should be a category separate from the working class, but my examination of media coverage suggests that the working class and working poor are discussed somewhat interchangeably, particularly as more working-class employees are “only a step—or a second family income—away from poverty.”11 As a result, societal lines, like media distinctions, between the working class and working poor have become increasingly blurred. Global shifts in the labor force through outsourcing, downsizing, and plant closings have created more fluidity between the two groups.

…

Global shifts in the labor force through outsourcing, downsizing, and plant closings have created more fluidity between the two groups. Some analysts place the working poor at 13 percent of the U.S. population; so, when combined with the working class (30 percent), these two categories together constitute approximately 43 percent of the population. Even under the best of circumstances, the working poor hold low-wage positions with little job security, few employee benefits, and no chance to save money. Their work conditions are frequently unpleasant and sometimes dangerous.12 The working poor may include illegal immigrants (known as undocumented workers) who worry that they will be incarcerated or deported if they complain to employers about wages or working conditions.

The Rich and the Rest of Us

by

Tavis Smiley

Published 15 Feb 2012

It concludes that the “well-being of low-income Americans, particularly the working poor, the near poor, and the new poor, are at substantial risk,” despite politicians’ and Wall Street’s declarations of an economic recovery.37 With the economic reality that real wages for the American working class have not increased for the past four decades, it is past time to challenge the distorted language and accompanying political rhetoric about the poor. We must move past Republican and Democratic versions of trickle-down economics—the belief that helping the rich and middle classes will magically improve the lot of the poor and working poor. Job growth has stalled so badly that several economists predict that, even if the economy rebounds, unemployment levels by the end of 2013 may return only to 2007 levels—around 4.6 percent, or almost 14 million people.

…

We want to pin the tail on any available donkey that will keep us from having to define poverty as “being unable to make a living because we can’t find a job.” LONG LIVE THE LIE For at least the past four decades, most Americans have been able to ignore the poor and deny the extent of poverty. Middle class people would disparage low-income people, low-income people would dog the working poor, and the working poor would beat down on the homeless poor—because we all want to feel like we have some sort of stature in life. Be it shame and blame or utter disdain, all these attitudes were justified by stereotypes, distortions, and lies about the poor. It took the Great Recession to make poverty a real threat to the American psyche.

…

We are concerned about poverty in America because it has impacted our lives, our outreach, the missions we’ve embraced, and our roles as democratic thinkers. For my dear brother, Tavis, poverty is not an abstraction; it was the story of his childhood. He didn’t grow up associating poverty with Black ghettos, run-down barrios, or slums. Tavis, the oldest of ten kids, grew up in a Bunker Hill, Indiana, trailer park with mostly poor whites. His working-poor, struggling parents, Emory and Joyce Smiley, and his grandmother (Big Mama) ran a strict Pentecostal household in a space that wasn’t built for 13 people. When Tavis’s aunt was murdered, the Smiley home became the safety net for her four children. He still recalls the humiliation of going to school in hand-me-down clothes and shoes with cardboard stuffed in them to cover the holes in the soles.

Shortchanged: Life and Debt in the Fringe Economy

by

Howard Karger

Published 9 Sep 2005

Sixty percent of American workers earn less than $14 an hour, and unskilled entry-level workers in many service occupations earn $7 an hour or less.15 The working poor are also more vulnerable to the vicissitudes of life than the middle class. For example, more than 40 million Americans lack health insurance, and unanticipated events such as illnesses or family emergencies may require workers to take off time without pay, leading to a temporary shortfall in income and increased debt. Given the low incomes of the working poor, it’s not surprising that a fringe economy that promises quick cash with few questions asked has become a high-growth sector.

…

Chapter 1 looks at the scope and size of the fringe economy and the characteristics of its customers. It then examines the major players in the fringe economy, including mainstream financial institutions. Chapter 2 explores key factors that explain the phenomenal growth of the fringe sector, including stagnant wages, the rising numbers of working poor, the impact of welfare reform, immigration, and the rise of the Internet. Chapter 3 looks at the functionally poor middle class, an economic group increasingly targeted by the fringe sector. It also investigates the role of household debt in the growth of the fringe economy. Having a credit card is almost a necessity in America’s plastic-driven society.

…

–ACE Cash Express, 2004 Annual Report 2 Why the Fringe Economy Is Growing The almost exponential growth of the fringe economy during the mid-1990s was baffling, especially since real incomes were rising and the numbers of people in poverty were dropping. Nonetheless, many factors came together to foster the phenomenal growth of the fringe economy, including the rise in numbers of America’s working poor, welfare reform, high levels of immigration, the growth of the Internet, the increased financial stress that slow wage growth and the rising cost of necessities placed on the middle class; and liberal federal banking laws. In simple terms, a major reason for the growth in the fringe economy is that 43% of Americans annually spend more than they earn.

The American Way of Poverty: How the Other Half Still Lives

by

Sasha Abramsky

Published 15 Mar 2013

Contents Acknowledgments PROLOGUEA Scandal in the Making PART ONE: THE VOICES OF POVERTY CHAPTER ONEPoverty in the Land of the Plutocrats CHAPTER TWOBlame Games CHAPTER THREEAn American Dilemma CHAPTER FOURThe Fragile Safety Net CHAPTER FIVEThe Wrong Side of the Tracks CHAPTER SIXStuck in Reverse PART TWO: BUILDING A NEW AND BETTER HOUSE INTRODUCTIONWhy Now? CHAPTER ONEShoring Up the Safety Net CHAPTER TWOBreaking the Cycle of Poverty CHAPTER THREEBoosting Economic Security for the Working Poor CODAAttention Must Be Paid Note on Sources and Book Structure Notes Index Acknowledgments The American Way of Poverty is a book with many benefactors and champions. I wish I could say that I woke up one morning with the concept fully formed in my mind, but I didn’t. Rather, there were an array of themes that I was exploring in my journalism and a slew of economic and political issues that, in the years surrounding the 2008 economic collapse, I found to be increasingly fascinating.

…

And then there were the pantry denizens escaping domestic violence who had run up against draconian cuts to the shelter system. One client, Wallace recalled, was a woman in her late forties, about to enter a shelter. “We got a request to provide her food because she has to bring her own food to the shelter. The programs that assist the working poor and the poor are in dire straits.” Variations on the stories from Appalachian Pennsylvania could be encountered in cities and regions across America. After all, an economic free-fall of the kind that the United States underwent after the housing market collapse and then the broader financial meltdown leaves carnage in its wake.

…

Unable to claim unemployment insurance, they live entirely on savings, on the largesse of friends and family, or on charity. Yet this isn’t a story only about those without work. In fact, America’s scandalous poverty numbers also include a stunning number of people who actually have jobs. They are author David Shipler’s “working poor,” men and women who work long hours, often at physically grueling labor, yet routinely find they can’t make ends meet, can’t save money, and can’t get ahead in the current economy. At the bottom of that economy, income volatility is peculiarly high; casual laborers and hourly employees routinely see their hours cut, their wages reduced, or their jobs eliminated during downturns.

The Working Poor: Invisible in America

by

David K. Shipler

Published 12 Nov 2008

—Austin American-Statesman “Splendidly animated by Shipler’s empathy—his ability to see people and more important to depict them, not as statistics or symbols of injustice, but as human beings.” —The Miami Herald “The Working Poor will make any relatively well-off reader look at the struggles of the poor differently.… [It] deserves a place on the American bookshelf next to Barbara Ehrenreich’s Nickel and Dimed.” —The Boston Globe “Shipler steers clear of diatribes, looking at human frailty and a spectrum of bosses and social services. With moving under statement, he develops a compassionate picture of the working poor.” —The Star-Ledger (Newark) “A work of stunning scope and clarity.… He brings the reader close enough to the challenges faced every day by his workers to make them feel it when the floor inevitably drops out beneath them.”

…

.… He brings the reader close enough to the challenges faced every day by his workers to make them feel it when the floor inevitably drops out beneath them.” —The Buffalo News “The scope and importance of David Shipler’s The Working Poor brings to mind Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle.” —Deseret News (Salt Lake City) “A powerful exposé that builds from page to page, from one grim revelation to another, until you have no choice but to leap out of your armchair and strike a blow for economic justice.” —Barbara Ehrenreich, author of Nickel and Dimed “There is no better book on poverty in America than The Working Poor because it describes in vivid detail the sort of day to day problems and the cycles that these folks are involved in … really thought-provoking in a very important way.”

…

I use it as imprecisely as it should be used, to suggest the lowest stratum of economic attainment, with all of its accompanying problems. No discussion of the working poor is adequate without a discussion of their employers, so they also appear in these pages—entrepreneurs and managers who profit from cheap labor or who struggle to keep their businesses alive. In addition, this journey encounters teachers, physicians, and other professionals who try to make a difference. Although I have not sought to be demographically representative, most of the working poor in this book are women, as are most of them in the country at large. Unmarried with children, they are frequently burdened with low incomes and high needs among the youngsters they raise.

$2.00 A Day: Living on Almost Nothing in America

by

Kathryn Edin

and

H. Luke Shaefer

Published 31 Aug 2015

Drawing on Ellwood, the new president’s plan would add time limits to AFDC, but it would also increase the benefits of work to poor parents through a dramatic expansion of the EITC. By doing this, he argued, the country would “make history. We will reward the work of millions of working poor Americans by realizing the principle that if you work forty hours a week and you’ve got a child in the house, you will no longer be in poverty.” As Clinton was announcing plans to bolster the efforts of the working poor—whom many saw as deserving, but for whom there was little to no aid—he once again borrowed from Ellwood, making the case that the working poor “play by the rules” but “get the shaft.” It was time to “make work pay.” According to Jason DeParle, however, Ellwood worried that Clinton’s rhetoric on welfare time limits was too harsh.

…

We’ve seen that David Ellwood’s 1988 manifesto, Poor Support, called for replacing welfare, not just reforming it. He turned a spotlight on a portion of the poor who rarely got any attention—or much help—from the government: the working poor. Ellwood believed that by shifting the social safety net to support those who worked but remained in poverty, America could design a form of poor support that would avoid the criticisms lodged against welfare. In the 1990s, President Clinton and Congress acted on Ellwood’s ideas and bolstered the well-being of working-poor parents dramatically through tax credits that provided a substantial pay raise in the form of a wage subsidy. The largest of these programs, the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), is now generous enough to lift more than 3 million children above the poverty line each year.

…

Perhaps his only mistake was in assuming that this failure at the very bottom of the economic distribution would be visible and obvious, when in fact, throughout history, American poverty has generally been hidden far from most Americans’ view. America’s cash welfare program—the main government program that caught people when they fell—was not merely replaced with the 1996 welfare reform; it was very nearly destroyed. In its place arose a different kind of safety net, one that provides a powerful hand up to some—the working poor—but offers much less to others, those who can’t manage to find or keep a job. This book is about what happens when a government safety net that is built on the assumption of full-time, stable employment at a living wage combines with a low-wage labor market that fails to deliver on any of the above.

Creating Unequal Futures?: Rethinking Poverty, Inequality and Disadvantage

by

Ruth Fincher

and

Peter Saunders

Published 1 Jul 2001

The idea that government transfers are able to offset inequalities in the labour market is central to the current debate. It implies that Australia can ‘deregulate’ its labour market and yet not develop a working poor comparable to the United States (see especially the BCA 1999). How soundly based are these arguments? THE WORKING POOR AND LOW-WAGE HOUSEHOLDS Does Australia already have a ‘working poor’? In his overview of income poverty since the 1970s, Anthony King observed: Signs of the emergence of a group of working poor have been a repeated feature of recent poverty estimates and are in marked contrast to the situation in the early 1970s when employment was a virtual guarantee against poverty.

…

(King 1998, p. 100) Research by Buchanan and Watson (1997) and Eardley (1998) suggests that the working poor is still a minor presence in the economic landscape. It is, however, a group whose numbers are growing and whose presence could mushroom if extensive labour market deregulation were to occur. An important part of the argument favouring labour market deregulation relies on the distinction between the hourly wages paid to individuals and the income received by households. Low hourly wages, it can be argued, do not actually place a person among the working poor. Sue Richardson, for example, has argued: There are a number of reasons for being cautious about the presumption that low wages equate with low incomes.

…

Employers would simply substitute ‘subsidised’ workers (those on the lower pay) for ‘unsubsidised workers’. On the other hand, a large reduction in relative wages would lead to a major decline in living standards among the low-paid workforce and an increase in the size of the ‘working poor’ in Australia. In recognition of the problems of the ‘working poor’, the Five Economists have also suggested an earned income tax credit (EITC) scheme to compensate low-paid workers for their wage cuts. The American experience of the EITC suggests that earned tax credits are a successful response to the problem of welfare poverty traps and may warrant further examination (Ellwood 1999; Burtless 1998a and 1998b; Hout 1997).

Two Nations, Indivisible: A History of Inequality in America: A History of Inequality in America

by

Jamie Bronstein

Published 29 Oct 2016

The new programs also offered insufficient support to people with mental illnesses and substance abuse problems that hampered their ability to get jobs.49 Clinton’s administration had greater success in addressing inequality caused by low wages. Americans had been distinguishing between the unworthy poor and the worthy, working poor since the era of the Great Society. During the Clinton administration some questioned the existence of the category “the working poor.” For example, the economist Bradley Schiller denied that people could work full time and still head poor families, showing little understanding that contingent workers are not in control of their schedules, yet often have to maintain open availability, and that one can work less than full time but still too many hours to have the sort of availability that permits a second job.50 Clinton’s administration combatted working poverty by expanding the Earned Income Tax Credit, acting on the premise that that no family with a fully employed household head should be living beneath the poverty line.51 The administration also managed to increase the minimum wage, although only through a bargain with Republicans that resulted in tax cuts for small businesses.52 Health care costs, and the costs of untreated illnesses, were major sources of inequality.

…

The New York Times in 2005 ran a series of articles on class, pointing out for its readership that, contrary to popular belief, the United States is not the most upwardly mobile country in the world.9 A number of recent books question the notion that deregulation, budget cuts to safety nets, free trade promotion, and privatization have promoted growth to benefit all.10 Despite its length and serious subject matter, economist Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century (2014) was widely read and reviewed. Historian Steven Fraser’s Age of Acquiescence (2015) compared the modern American public unfavorably with Americans in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, who were not afraid to call out class warfare against the working poor when they saw it.11 Former Secretary of Labor Robert Reich’s documentary Inequality for All (2013) reached a wide audience, with an accessible message: the prosperity of the United States hinges on the middle class having an income to spend. After all, a multimillionaire can only drive one car at a time, wear one change of clothing at a time, sleep on one or two pillows at a time.

…

They traveled more than 2,000 miles before one of their leaders absconded with their entire treasury.112 Coxeyites in Oregon also attempted to steal a train; Attorney General Richard Olney foiled their plans by using federal troops to protect the trains because the transcontinental lines were in federal receivership.113 Coxey’s own Massillon, Ohio, contingent of only a few hundred protesters reached the nation’s capitol in May 1894, singing songs set to the tune of popular folk songs: There’s a deep and growing murmur Going up through all the land From millions who are suffering Beneath Oppression’s hand No charity, but justice Do the working poor demand And justice they will gain.114 While Attorney General Olney filed injunctions to keep Coxey’s Army from important buildings, these protests showed that, pushed far enough by inequality, the American poor could take direct action. Coxey himself lived until 1951, long enough to claim that his demands had been the basis for Roosevelt’s New Deal.

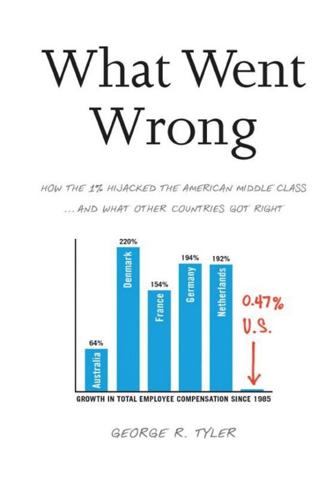

What Went Wrong: How the 1% Hijacked the American Middle Class . . . And What Other Countries Got Right

by

George R. Tyler

Published 15 Jul 2013

While performing identical tasks, they’re the ones wearing brown, not Nissan blue or gray. This downward spiral in wages has caused many reliable employees with solid job skills, but without college educations, to fall from the middle class to the ranks of the working poor. As labor economist Harley Shaiken at the University of California, Berkeley noted, family incomes for many now hover around the eligibility level for food stamps.19 Eroding wages has made this cohort of working poor enormous, as described by MIT economist Paul Osterman in August 2011: “Last year, one in five American adults worked in jobs that paid poverty-level wages. Worker displacement contributes to the problem.

…

While worksite relations have deteriorated, jobs offshored, and wages flattened for most employees, the most severely impacted may be the most vulnerable: Working poor men and women victimized by employers violating national wage and hour laws. An authoritative analysis of employer wage embezzlement was jointly conducted in 2009 by the University of California at Los Angeles, the Center for Urban Economic Development, and the National Employment Law Project. Their analysis focused on the working poor, that 20 percent of adults earning around the minimum wage. These employees tend to be the least assertive and informed and consequently more subject potentially to employer abuse.

…

Raising the minimum wage is also preferable to expanding the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), an income-based welfare benefit program targeted at the working poor. Funded from general revenues administered through the federal tax system, the EITC can be carefully targeted, making it a cost-effective favorite among economists. However, unlike the minimum wage, it does not incentivize employers to upskill. In addition, it has limited coverage, because the working poor must file tax returns to obtain benefits. Moreover, it’s bureaucratic and expensive to operate. Its complexity further reduces its effectiveness: there are 50 pages of instructions for single mothers and others to follow when filing for the tax benefit.51 Finally, like food stamps and other support received by the working poor, the EITC is an opaque taxpayer subsidy to low-wage employers whose balance sheets in many instances are far stronger than those of taxpayers.

Strangers in Their Own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right

by

Arlie Russell Hochschild

Published 5 Sep 2016

Families are classified either as married-couple families or as those maintained by men or women without spouses present. Bureau of Labor Statistics, A Profile of the Working Poor, 2013 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Labor, 2015), http://www.bls.gov/opub/reports/cps/a-profile-of-the-working-poor-2013.pdf. For the racial composition of working-poor families, see Deborah Povich, Brandon Roberts, and Mark Mather, Low-Income Working Families: The Racial/Ethnic Divide (Working Poor Families Project and Population Reference Bureau, 2015), http://www.workingpoorfamilies.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/WPFP-2015-Report_Racial-Ethnic-Divide.pdf. 256the rest was payment for work According to the Congressional Budget Office, in 2011 (the latest available), households in the lowest quintile of income (adjusted for household size) received an average of $9,100 in government transfers (cash payments and in-kind benefits from social insurance and other government assistance programs from federal, state, and local governments); that amounts to about 37 percent of an average pre-tax income of $24,600.

…

PunditFact, January 28, 2015, http://www.politifact.com/punditfact/statements/2015/jan/28/terry-jeffrey/are-there-more-welfare-recipients-us-full-time-wor (based on Census and Bureau of Labor statistics). 256Medicaid or Children’s Health Insurance Program recipients Ken Jacobs, Ian Perry, and Jenifer MacGillvary, “The High Public Cost of Low Wages,” April 13, 2015, under section entitled, “The High Cost of Low Wages,” http://laborcenter.berkeley.edu/the-high-public-cost-of-low-wages. 256All Earned Income Tax Credit recipients work Jason Furman, Betsey Stevenson, and Jim Stock, “The 2014 Economic Report of the President,” March 10, 2014, https://www.whitehouse.gov/blog/2014/03/10/2014-economic-report-president. 256among homecare workers, 48 percent did so Jacobs, Perry, and MacGillvary, “The High Public Cost of Low Wages.” The Bureau of Labor Statistics produces a yearly “profile of the working poor.” In 2013, the BLS found that 5.1 million families in the United States were living below the poverty level, despite having at least one member in the labor force for half the year or more. The “working-poor rate”—the ratio of the working poor to all individuals in the labor force for at least twenty-seven weeks—was 7.7 percent for families (which the BLS defines as a group of two or more people residing together who are related by birth, marriage, or adoption).

…

Department of Labor, 2014 (accessed September 2, 2014). http://stats.bls.gov/ces/#data. _______. Mass Layoff Statistics [2012 data]. Washington, D.C.: Department of Labor, 2012 (accessed March 13, 2014). http://www.bls.gov/mls. _______. A Profile of the Working Poor, 2013. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Labor, 2015. http://www.bls.gov/opub/reports/cps/a-profile-of-the-working-poor-2013.pdf. _______. “Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages [December 2014 estimates]” (accessed June 18, 2015). http://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/dsrv?en. “Cancer Facts and Figures 2015.” American Cancer Society. http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@editorial/documents/document/acspc-044552.pdf.

Squeezed: Why Our Families Can't Afford America

by

Alissa Quart

Published 25 Jun 2018

Still a Bernie Sanders supporter a year after the election, Bellamy bristled at the memory of the 2016 primaries. She was now researching her new book project, “Jyeshtha, the Hindu God of Misfortune.” Misfortune was indeed a subject that for her would seem apropos for our times. THERE ARE BOTH SMALL AND LARGE REMEDIES FOR THE PLIGHT OF the hyper-educated working poor—those earning around $36,000 a year, with kids, and just getting by, only a few false moves away from the poverty line. For underpaid and often desperate adjunct instructors, one particular remedy is what I think of as “unusual unions.” The last five years have seen a rise of atypical union members, like adjuncts, despite the downturn in labor membership overall.

…

Unlike those who must put their children in extreme day care and the day-care workers who overwork to serve them, Blanca was both the most squeezed of parents and day-care providers—so pressed that she had to leave her son for a decade back home, where he grew up without her. Now Blanca had to make another hard choice: whether to pay the price of getting her son back by replacing his middle-class life in Paraguay with becoming part of the working poor in America. This hasn’t always been the only choice: as the Columbia University historian Alice Kessler-Harris, author of Women Have Always Worked, tells it, at the turn of the last century and at different points in the twentieth century, America was indeed a land of opportunity. Immigration was always difficult, but it could be a pathway to success.

…

Guido’s life itself resembled a linear equation, with determinate factors and indeterminate ones, Y and X variables, like in math class. The good determinate factors were his inherent physical grace and the love of his mother and grandmother. The bad determinate factors were the language barrier and living in near poverty in a fractured family. And the indeterminate factor was luck. When working-poor New Yorkers like Blanca and Guido seek spots at the city’s more desirable schools, they often must compete with middle-class New Yorkers. The competition isn’t set up to be even. So many challenges face those who are knocking on the door. There is a persistent failure in urban schools to find bilingual communicators, even in the most diverse cities.

The Last President of Europe: Emmanuel Macron's Race to Revive France and Save the World

by

William Drozdiak

Published 27 Apr 2020

But for those earning an average income of 1,700 euros (about $2,000) per month, it has become harder to make ends meet with the rising cost of basic necessities like food, shelter, and transport. Over the past fifteen years, the tax burden on French citizens has grown by 25 billion euros ($28 billion) a year, with a disproportionate share borne by the working poor. By the time of the Yellow Vest movement, the steady erosion of purchasing power for lower-middle-class families over the past decade had evolved, almost unnoticed by the government, into a genuine social emergency. Although many protesters said that they approved of the government’s ambition to do something about climate change, they objected to carrying so much of the fiscal burden, particularly when cosmopolitan elites were spared onerous taxes for traveling in planes, which pollute more than cars do.

…

During an eight-day tour of World War I battlefields ahead of the centennial anniversary marking the armistice that ended one of history’s most hideous wars, Macron confronted many resentful citizens across France, who complained that he was too remote from their everyday lives and did not seem to care or understand the true nature of their hardships. They, like him, were frustrated that the fruits of his reform efforts were so slow in coming. Even Macron’s wealthiest supporters accused him of being tone-deaf to the problems of the working poor. François Pinault, whose business empire includes the Gucci fashion house, told the newspaper Le Monde that “Macron doesn’t understand the little people. I’m afraid he’s leading France toward a system that leaves the least favored behind.”9 Matthieu Pigasse, a prominent financier who heads the Lazard investment bank in France, told the business newspaper Les Echos that Macron needed to show more empathy for the lower classes.

…

The anger and frustration showed the depth of resentment in the rural areas that had not thrived in recent years. The growing divide between rich and poor—the richest 20 percent of French people, according to the World Bank, now earn nearly five times as much as the bottom 20 percent—makes a mockery of French pretensions of “liberty, equality and fraternity.” That yawning divide, in turn, heightens the working poor’s disillusionment with Macron, who took office on a cloud of euphoria amid hopes for a resurgence in economic growth that would lift up the entire nation. “The system is in crisis,” said French political scientist Dominique Reynié. “It’s the provinces against Paris, the proud and contemptuous capital.

Brave New World of Work

by

Ulrich Beck

Published 15 Jan 2000

For it increases the supply of flexible temporary labour and weakens the individual's position in the grey economy, resulting in a further loss of income. ‘If there are no mechanisms to limit cost-cutting competition among the suppliers of labour, a danger arises of self-reinforcing processes of impoverishment.’62 And this arises as a result of work. Work and poverty, which used to be mutually exclusive, are now combined in the shape of the working poor. Unemployment, non-work, grey work Unemployed people have a lot of time on their hands and are financially very insecure. But paradoxically, their receipt of unemployment benefit obliges them to do nothing. They might almost be compared to thirsty people who have to promise not to drink one drop of extra water, because they are officially given one glass a day to moisten their parched throat.

…

But this is a transition, and as long as it lasts it will be painful to many people – especially to men, who cannot get used to the fact that the rigid idea of a lifetime career opportunity will no longer mean much in the future.63 But the downward elevator effect into the world of job insecurity does not affect everyone equally. As in the past, it is true internationally that insecure and temporary forms of employment are increasing faster among women than among men. Women make up by far the larger part of the working poor, and for them in particular the systemic change that is opening up a grey area between work and non-work takes place as a descent into poverty. Nor does the growing number of men confronted with insecure and fragmented working lives result in any positive easing of the gender conflict. Indeed, in so far as the reign of the short term also undermines relations of partnership, love, marriage, parenthood and family, men suffer as much as women – and public life too dies out.

…

Leisure time is a foreign word, social life – ‘vacations’ – an endemic problem. Anyone who cannot be reached anytime and anywhere is running a risk. Such ‘individual responsibility’ lifts a burden from the public and corporate coffers and makes the individual the ‘architect of his or her own fortune’. The working poor. The jobs of ‘low-skilled’ and ‘unskilled’ workers are directly threatened by globalization. For they can be replaced either by automation or by the supply of labour from other countries. In the end, this group can keep its head above water only by entering into several employment situations at once.

When Work Disappears: The World of the New Urban Poor

by

William Julius Wilson

Published 1 Jan 1996

As I pointed out earlier, the most impoverished inner-city neighborhoods have experienced a decrease in the proportion of working- and middle-class families, thereby increasing the social isolation of the remaining residents in these neighborhoods from the more advantaged members of society. Data from the UPFLS reveal that the non-working poor in the inner city experience greater social isolation in this sense of the term than do the working poor. Nonworking poor black men and women “were consistently less likely to participate in local institutions and have mainstream friends [that is, friends who are working, have some college education, and are married] than people in other classes” and ethnic groups.

…

Graduated job ladders would provide rewards to workers who succeed on the job, “but wages would always be lower than [that which] an equally successful worker would receive in the private sector.” These wages would be supplemented with the expanded earned income tax credit and other wage supplements (including a federal child care subsidy in the form of a refundable income tax credit for the working poor and refundable state tax credits for the working poor). The Danziger and Gottschalk proposal obviously would not provide a comfortable standard of living for the workers forced to take public service jobs. Such jobs are minimal and are “offered as a safely net to poor persons who want to work but are left out of the private labor market.”

…

Drug abuse was cited as a major problem by as many as 86 percent of the adult residents in Oakland and 79 percent of those in Woodlawn. Although high-jobless neighborhoods also feature concentrated poverty, high rates of neighborhood poverty are less likely to trigger problems of social organization if the residents are working. This was the case in previous years when the working poor stood out in areas like Bronzeville. Today, the nonworking poor predominate in the highly segregated and impoverished neighborhoods. The rise of new poverty neighborhoods represents a movement away from what the historian Allan Spear has called an institutional ghetto—whose structure and activities parallel those of the larger society, as portrayed in Drake and Cayton’s description of Bronzeville—toward a jobless ghetto, which features a severe lack of basic opportunities and resources, and inadequate social controls.

The New Class War: Saving Democracy From the Metropolitan Elite

by

Michael Lind

Published 20 Feb 2020

The gap between richest and poorest in New York City is comparable to that of Swaziland; Los Angeles and Chicago are slightly more egalitarian, comparable to the Dominican Republic and El Salvador.4 Meanwhile, in the vast areas of low-density, low-rise residential and commercial zones around and among the hierarchical hubs, a radically different society has evolved. In the national heartlands, apart from expensive rural resort areas, there are fewer rich households and therefore fewer working poor employed by the rich as servants and luxury service providers. In the US and Europe, the population of the heartlands is much more likely to be native-born and white. But the heartlands are becoming more racially and ethnically diverse, making the familiar equation of “urban” and “nonwhite” anachronistic.

…

Heartland communities are more likely to be sensitive to the costs of environmental policies than hub city managers and professionals. What is more, the property-owning, working-class majorities of the heartlands are also likely to be more sensitive to environmental restrictions on what property owners can do with their property than the denizens of the hubs, where not only the working poor and the working class but also many professionals must rent because they cannot afford to own homes. And most working-class individuals in low-density regions rely on their personal cars or trucks for commuting, shopping, and recreation. The French yellow vest riots of the winter of 2018–19 illustrated the intersecting fault lines of class and place in environmental policy.

…

As split labor market theory would predict, the native working-class backlash has been greatest against particular groups of immigrants, nonwhite or white, who are viewed as competitors for jobs or welfare and public services. * * * — THE GEOGRAPHIC POLARIZATION that is evident in Western democracies, then, reflects the social divide among classes who live in different areas—college-educated overclasses and the disproportionately immigrant working poor in the high-density hubs and the mostly native, mostly white working classes in the low-density heartlands. Their differences over environmental policy, trade, immigration, and other issues reflect conflicting interests, values, lifestyles, and aspirations. Can today’s new class war, fought on all of these different fronts at once, give way to a new class peace?

Give People Money

by

Annie Lowrey

Published 10 Jul 2018

Allegretto, Marc Doussard, Dave Graham-Squire, Ken Jacobs, Dan Thompson, and Jeremy Thompson, “Fast Food, Poverty Wages: The Public Cost of Low-Wage Jobs in the Fast-Food Industry” (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and the UC Berkeley Labor Center, Oct. 15, 2013). 9.5 million people…remained below the poverty line: Center for Poverty Research, “Who Are the Working Poor in America?,” https://poverty.ucdavis.edu/faq/who-are-working-poor-america. the bottom half of earners: Thomas Piketty, Gabriel Zucman, and Emmanuel Saez, “Share of Income for the Top 1 and Bottom 50 percent of the Income Distribution,” raw data, World Wealth & Income Database, wid.world. The middle class is shrinking: Pew Research Center, “The American Middle Class Is Losing Ground: No Longer the Majority and Falling Behind Financially” (Washington, DC, Dec. 9, 2015).

…

Luis and Josefa talked about the pressure and the stress of their uncertain schedules, and the strain of knowing their children were growing up deprived. At the end of her shift at Raising Cane’s, climbing into Luis’s car, one of the Ortiz daughters told me that she often did not eat dinner. “The smell of the chicken fills me up,” she said. The working poor, the precariat, the left behind: this is modern-day America. We no longer have a jobs crisis, with the economy recovering to something like full employment a decade after the start of the Great Recession. But we do have a good-jobs crisis, a more permanent, festering problem that started more than a generation ago.

…

“Now that I have a basic income, I know my work has value. I know my time has value. I know I have value.” In Santens’s mind, a UBI is not a salve for a world of technological unemployment, or a powerful antipoverty measure, or a form of social dividend, or a way to boost the earnings of the working poor. Rather, it is all those things and more: a paradigmatic shift that would free people from having to do work that they did not want to do at all. A UBI would, in essence, lop off the bottom of the psychologist Abraham Maslow’s “hierarchy of needs,” where air, food, water, and shelter reside, with self-transcendence up at the other end.

Bikenomics: How Bicycling Can Save the Economy (Bicycle)

by

Elly Blue

Published 29 Nov 2014

National Housing Conference and Center for Housing Policy, “Losing Ground: Housing and Transportation Costs Outpacing Incomes,” 2012. 24 The working poor spend more on both housing and commuting; homeowners living in poverty spend on average 25% of their income on housing, compared with 15% among the non poor. Renters spend 32% of their income on housing, compared with 20% among the non-poor. Brookings Institute, “Commuting to opportunity: The working Poor and Commuting in the United States,” 2008 25 The first paved bike path in Oregon was privately funded, with local wheelmen kicking in $1 each to pave the road to The White House, a bar in southwest Portland.

…

In 2009, people at every income level spent more on transportation than they did on food.8 Among households that made under $70,000, nearly 20% of their annual spending went to transportation (though even with incentives that year to buy new cars, including the huge federal Cash for Clunkers9 program, people were clearly economizing—far less was spent overall than in the year before). And the working poor seemed to have it the worst that year—65% drove a car to work and reported spending between 8% and 9% of their income on gas alone.10 For further perspective, the poverty line in the U.S. in 2011 was calculated at $10,830 for a single person a year. This measure is based on the cost of food; a cost which has gone down over the last century even as other expenses, particularly transportation and housing, have gone up significantly.

…

Car ownership was seen as a path to employment, especially for low-income single mothers, and as a viable alternative to subsidizing public transportation. They made some good points. When you’re poor, you are often geographically isolated and lack good access to jobs. Transit systems in many cities don’t well serve the needs of the working poor, and most have cut back service even from where it was a decade ago. Low income people often resort to predatory loans in order to get a car. And there is a real correlation between employment and car ownership. In many cases, it’s the best of the bad options available. My sympathy for this case was dismantled piece by piece over the course of the morning.

Work in the Future The Automation Revolution-Palgrave MacMillan (2019)

by

Robert Skidelsky Nan Craig

Published 15 Mar 2020

Are the French citizens, and French dissatisfied people, spoilt citizens that fear the end of welfare improvement, or is dissatisfaction mainly an issue of composition effects (Murphy and Topel 2016; INSEE 2017)? We should go further in the investigation of the paradox. The second point is dissatisfaction with pay and low confidence in the future. France’s choice has been to reject the ‘working poor’ model. The minimum wage is among the highest of OECD countries. Over the last 55 years, it has increased faster than the inflation rate and faster than the average wage over the last 20 years. France has indeed a fairly redistributive policy that lowers income inequality and manages to have a rather low share of people below the poverty line.

…

Yet, this generates dissatisfaction with pay, especially among those who invest in higher education and expect a good return from it (Artus 2017). The so-called talent drain in France builds on this unbalanced return on education and advancement. There is now also a growing concern about the momentum that the working poor model gains in France and about the costs of the fairly tight safety net used to buffer it. In fact, the polarisation of the labour market paves the way for a growing structural inequality. Jobs are concentrating at the two extremities: skilled and well-paid jobs in sophisticated sectors, and unskilled and/or deskilled low paid jobs in unsophisticated services.

…

When asked about how confident they are in their ability to keep their job over the coming months, the French are amongst the most likely to say they are not very confident. For sure, unemployment in France is high and has remained so for more than three decades, yet it mainly hits the low skilled to a greater extent than in the US or the UK, due to the rejection of the working poor model. At the same time, unemployment benefits and unemployment compensation duration in France are among the highest in Europe. The combination of strict employment protection laws and generous unemployment insurance has backed a strong insider/ outsider duality in the labour market, with strong discrepancies between permanent jobs and temporary fixed term contract jobs (OECD 2017).

Off the Books

by

Sudhir Alladi Venkatesh

That research culminated in a book, American Project: The Rise and Fall of a Modern American Ghetto, that documented everyday living conditions in these high-rises, which are now being demolished in the effort to deconcentrate poverty and revitalize inner cities. Along the way, I was hanging out in the working-poor communities surrounding the housing development. These streets were the epitome of the ghetto—-that fabled place in American culture that countless journalists have lamented, almost as many academics have analyzed, and more than a few politicians have promised to fix. These neighborhoods conformed to, but also showed the gross oversimplification of, our stereotypes about the ghetto.

…

Commercial corridors filled with low-income retail outlets—currency exchanges, liquor and "dollar" stores, fast-food chains—were slowly attracting the attention of real estate speculators who envisioned large shopping malls and who were resting their bets on rising incomes (or an influx of wealthier families). But in the early and mid nineties, much of Chicago's Southside was still primarily a working-poor black community. Families had been there for generations, living modestly and in a near-continuous state of economic vulnerability. I was drawn to a community of roughly ten square blocks in Chicago's Southside that I will call "Maquis Park" (most of the names for places and people in this book are pseudonyms).

…

However, as we have seen, the underground economy manages to touch all households, whether as a direct source of income, as a place to acquire cheap goods and services, or as a part of the public theater. Thus, it is not so easy to separate the innocent from the perpetrator. The same person who despises the gang's drug trading may depend on a member of the household to bring money into the home by fixing cars off the books. Fixing cars is not equivalent to dealing drugs, but as Chicago's working poor entered the year 2000, the gang's advances were making very blurry the lines that divided shady traders from one another. When good and bad have become very relative terms, how do you solve your problems? Since the early twentieth century, kids growing up in cities have been tempted to join their local street gang.

The Gospel of Food: Everything You Think You Know About Food Is Wrong

by

Barry Glassner

Published 15 Feb 2007

Mark Warbis, “Suit Says Albertson’s Forces Unpaid Work,” Associated Press, April 22, 1997; “Supermarket Strike Averted,” East Bay Business Times, January 24, 2005. 6. See also Egger, pp. 107–8; “A Profile of the Working Poor,” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, March 2005. 7. Jianghong Liu, Adrian Raine, et al., “Malnutrition at Age 3 Years and Externalizing Behavior Problems at Ages 8, 11, and 17 Years,” American Journal of Psychiatry 161 (2004): 2005–13; David Shipler, The Working Poor (New York: Knopf, 2004), chap. 8; Irwin H. Rosenberg et al., “Statement on the Link Between Nutrition and Cognitive Development in Children,” Center on Hunger and Poverty, Brandeis University, 1998. 8.

…

Furthermore, he had acknowledged earlier in our interview that low-paid workers routinely show up in food lines. Many of the people America’s Second Harvest assists “have to make decisions between rent and food and medicine, or food and housing, or food and utilities,” Forney said. “Those are the decisions that working poor people have to make, and unfortunately, that means that we’re seeing a lot more people.” Each of the several leaders of hunger-relief agencies I consulted commented on the absurdity (immorality, some called it) of a wage system in which people who work forty or fifty hours a week cannot afford basic food and shelter for themselves and their children.

…

Cost information is from Kroc, p. 178; Burger King’s and McDonald’s Web sites; www.entrepreneur.com; and “McDonald’s Makes Franchising Sizzle,” BusinessWeek, June 15, 1968, pp. 102–3. 49. Talwar, chap. 8. 50. Talwar (quote is from p. 2). 51. Quote is from Talwar, p. 2. See also David Shipler, The Working Poor (New York: Knopf, 2004), p. 19. 52. Schlosser, Fast Food Nation, pp. 75–83, 265. 53. Recycling quote is from Donna Fenn, “Veggie-Burger Kings,” Inc. (November 2001): 44. 54. McDonald’s quote is from the company’s Web site; Anderson is quoted in Josef Woodard, “Her Private Happy Meal,” Los Angeles Times, January 27, 2002.

A People's History of Poverty in America

by

Stephen Pimpare

Published 11 Nov 2008

I have a family to support—I need a real job.16 One former welfare recipient, a Native American woman, said it this way: I want to give my kids someone to look up to. People should work if they can. I was embarrassed being on welfare. People think you’re lazy. I wanted to better my future. I don’t want to depend on my family. I’m an independent woman.17 But the desire for work does not necessarily translate into the ability to work: poor Americans often have less education and fewer skills, which limits their options to jobs with low pay, few benefits, and little security.18 Such jobs seldom pay enough to cover child care. Poor women are twice as likely as those with incomes above 200 percent of the poverty line to have health problems, and about half of all women on welfare report having poor physical or mental health (other studies suggest that about one in four women with experience of welfare had problems with their mental health).

…

There have to be some mothers in the neighborhood who are going to do this, or none of the mothers, even the ones who want to work, are going to be able to work.17 As Katherine Newman attests:It takes time to monitor public space. Mothers on welfare often shoulder the burden for working mothers who simply cannot be around enough to exercise vigilance. They provide an adult presence in the parks and on the sidewalks where it is most needed. Without these stay-at-home moms in the neighborhood, many a working-poor parent would have no choice but to force the kids to stay at home all day.18 This is the point that urbanist Jane Jacobs has made about the importance of a watchful eyes and mutual policing for a healthy, safe neighborhood. 19 And there’s this interesting observation by one journalist writing about recipients in Washington, D.C.

…

Official data will not get us far in evaluating or understanding the lived experience of poor Americans, which is why I have chosen not to privilege these measures in this book. Poverty over the Life Course There is another problem with most poverty data. Official rates are snapshots: they seek to count how many people are poor at any one point in time. But Americans move in and out of poverty over the course of their lives—the line between working, working poor, and poor can be very thin indeed. Many families are poor one year, not poor (at least officially so) the next, and then poor again the following year. One harsh winter, a fire, an epidemic or illness (cholera, smallpox, and yellow fever swept through the ghettoes in the past; today poor households face AIDS, diabetes, asthma, tuberculosis, or gun violence), divorce, the death or incarceration of the main breadwinner, an injury or disability, or the sudden loss of a job—these can push a family from just getting by into dire crisis.12 Thus, it would seem useful also to ask how many Americans are ever poor.

The New Division of Labor: How Computers Are Creating the Next Job Market

by

Frank Levy

and

Richard J. Murnane

Published 11 Apr 2004

Had the rest of the economy remained unchanged, the declining importance of blue-collar and clerical jobs might have resulted in the rising 4 CHAPTER 1 unemployment feared by the Ad Hoc Committee. But computers are Janus-faced, helping to create jobs even as they destroy jobs. As computers have helped channel economic growth, two quite different types of jobs have increased in number, jobs that pay very different wages. Jobs held by the working poor—janitors, cafeteria workers, security guards— have grown in relative importance.3 But the greater job growth has taken place in the upper part of the pay distribution—managers, doctors, lawyers, engineers, teachers, technicians. Three facts about these latter jobs stand out: they pay well, they require extensive skills, and most people in these jobs rely on computers to increase their productivity.

…

At any moment in time, the boundary 6 CHAPTER 1 marking human advantage over computers largely defines the area of useful human work.5 This boundary shifts as computer scientists expand what computers can do, but as we will see, it continues to move in the same direction, increasing the importance of expert thinking and complex communication as the domains of well-paid human work. What is true about today’s rising skill requirements will be even more true tomorrow. Who will have the skills to do the good jobs in an economy filled with computers? Those who do not will be at the bottom of an increasingly unequal income distribution—the working poor. The disappearance of clerical and blue-collar jobs from the lower middle of the pay distribution illustrates this pattern of limited job options. People with sufficient workplace skills can move from these jobs into one of the expanding sets of higher-wage jobs. People who lack the right skills drop down to compete for unskilled work at declining wages.

…

Smith used the term to describe the increased efficiency that came when a particular job—making a straight pin, in his example—was divided into a series of narrow tasks—making the heads of pins, making the stems, sharpening the points—with each task assigned to a specialized worker. 3. On the increase in the number of the working poor, see Barbara Ehrenreich, Nickel and Dimed: On (Not) Getting By in America (New York: Owl Books, 2001). 4. One of a limited number of exceptions was the mechanical calculator, which could perform basic arithmetic. 5. Strictly speaking, the determining factor is not humans’ absolute advantage but humans’ comparative advantage.

The Raging 2020s: Companies, Countries, People - and the Fight for Our Future

by

Alec Ross

Published 13 Sep 2021

researchers found that 40 percent of American households: Natasha Bach, “Millions of Americans Are One Missed Paycheck away from Poverty, Report Says,” Fortune, January 29, 2019, https://fortune.com/2019/01/29/americans-liquid-asset-poor-propserity-now-report/; “A Profile of the Working Poor, 2017,” US Bureau of Labor Statistics, April 2019, https://www.bls.gov/opub/reports/working-poor/2017/home.htm. Workers who received welfare payments: Henry Aaron, “The Social Safety Net: The Gaps That COVID-19 Spotlights,” Brookings Institution, June 23, 2020, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2020/06/23/the-social-safety-net-the-gaps-that-covid-19-spotlights/.

…

These growing expenses disproportionately affect low-income families, who already spend a larger chunk of their earnings on basic necessities than wealthier households. In 2019, researchers found that 40 percent of American households were one paycheck away from falling into poverty. The figure rose to 57 percent for nonwhite families, and that was before COVID hit. Today, millions of Americans belong to the working poor, living right around the poverty line despite holding a job. Private benefits also only work when people have jobs. As unemployment soared in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, millions of people lost health coverage at the time they needed it most. As people filed for unemployment, food stamps, and other benefits, US government safety net programs became overwhelmed.

…

There were 234 strikes involving a thousand or more workers per year on average in the United States in the five years before the PATCO strike. In the five years after it, the number fell to 72. Over the course of the 2010s, the average was 15. Joseph McCartin, director of the Kalmanovitz Initiative for Labor and the Working Poor at Georgetown University, said without the ability to strike, unions lost all their leverage. “More and more, employers wanted strikes because they could use a strike to break the union or severely weaken it,” McCartin told me. “As workers lost the ability to engage in strikes, even when they were in unions, they didn’t have the power they used to have.

Global Financial Crisis

by

Noah Berlatsky

Published 19 Feb 2010

The crisis finds the Israeli society in worse shape than it was during the last recession, that of 2000–2003: currently about a quarter of Israeli citizens live below the official poverty line, among whom the percentage of minority groups, such as Israeli Arabs and Orthodox Jews, is extremely high. A large part of the Israeli poor population are defined as “working poor,” meaning people who are employed and yet do not earn a minimum living wage, a phenomenon which is usually regarded as a symptom of the crumbling of the middle classes. The Financial Crisis Will Hurt Israelis Despite the fact that many governments around the world, from Europe to Mexico, are intending to increase spending in order to combat the oncoming recession, the Israeli government has already declared that it will keep a balanced budget 122 Effects of the Global Financial Crisis on Wealthier Nations and that, to do so, further cuts in social spending will be necessary.

…

The center also suggests that while some nations in Latin America have pursued responsible economic policies, others such as Nicaragua and Venezuela have not and may now experience instability. Despite possible turmoil, speakers note, the region is much more politically stable overall than in the past. As you read, consider the following questions: 1. According to Rebeca Grynspan, how many working poor people are there likely to be in Latin America in 2009? 2. According to Arturo Porzecanski, which countries are part of the “responsible left and right”? 3. When was the last military coup in Latin America, according to Jorge I. Domínguez? Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, “The Global Financial Crisis: Implications for Latin America,” A summary of an event hosted by the Latin American Program, Harvard University’s David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies and the Council of the Latin Americas/Americas Society at Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars on Febuary 5, 2009.

…

The middle class is also suffering, and a large population goes back and forth above and below the poverty line. The International Labour Organization estimates that the number of people living in “work poverty”—those active in the labor market but earning an income below the poverty line established by the World Bank—will rise from 6.8 percent in 2007 to 8.7 percent in 2009, constituting 7 million working poor. An additional 4 million people will lose their jobs in 2009 if growth rates, as projected, are only around 1 percent. Grynspan argued for a larger system of social protection to prevent huge reversals of the gains in reducing poverty in recent years. Programs should emphasize women and young people, who are twice as likely to be unemployed, while infrastructure investment should include small and community-based projects, not just largescale ones.

The Ghost Map: A Street, an Epidemic and the Hidden Power of Urban Networks.

by

Steven Johnson

Published 18 Oct 2006

(Unlike the typical new urbanist environment, however, Soho also had its share of industry: slaughterhouses, manufacturing plants, tripe boilers.) The neighborhood’s residents were poor, almost destitute, by the standards of today’s industrialized nations, though by Victorian standards they were a mix of the working poor and the entrepreneurial middle class. (By mud-lark standards, of course, they were loaded.) But Soho was something of an anomaly in the otherwise prosperous West End of the city: an island of working poverty and foul-smelling industry surrounded by the opulent townhouses of Mayfair and Kensington.

…

He had encountered the gossip that had been circulating in the past day, folk wisdom that would eventually find its way into the papers in the coming weeks: the residents of upper floors were dying at a more dramatic rate than those living on ground or parlor floors. There was a socioeconomic edge to this contention, one that reverses the traditional upstairs/downstairs division of labor: in Soho at the time, the bottom floors were more likely to be occupied by owners, with the upper floors rented out to the working poor. An increased death rate in the upper floors would suggest a fatal vulnerability in the constitution or sanitary habits of the poor. The notion, in its crude and haphazard way, was a version of Snow’s tale of two buildings in Horsleydown: put two groups of people in close proximity, and if one group turns out to be significantly more vulnerable than the other, then some additional variable must be at work.

…

Death was omnipresent, particularly for the working class. One study of mortality rates from 1842 had found that the average “gentleman” died at forty-five, while the average tradesman died in his mid-twenties. The laboring classes fared even worse: in Bethnal Green, the average life expectancy for the working poor was sixteen years. These numbers are so shockingly low because life was especially deadly for young children. The 1842 study found that 62 percent of all recorded deaths were of children under five. And yet despite this alarming mortality rate, the population was expanding at an extraordinary clip.

Inventing the Future: Postcapitalism and a World Without Work

by

Nick Srnicek

and

Alex Williams

Published 1 Oct 2015

Yet the language that framed the proposal maintained strict divisions between those who were working and those who were on welfare, despite the plan effacing such a distinction. The working poor ended up rejecting the plan out of a fear of being stigmatised as a welfare recipient. Racial biases reinforced this resistance, since welfare was seen as a black issue, and whites were loath to be associated with it. And the lack of a class identification between the working poor and unemployed – the surplus population – meant there was no social basis for a meaningful movement in favour of a basic income.125 Overcoming the work ethic will be equally central to any future attempts at building a post-work world.

…

William Julius Wilson, When Work Disappears: The World of the New Urban Poor (New York: Vintage Books, 1997), pp. 29–31. 34.Michael McIntyre, ‘Race, Surplus Population, and the Marxist Theory of Imperialism’, Antipode 43:5 (2011), p. 1500–2. 35.These draw broadly upon the divisions Marx drew between the floating/reserve army, latent and stagnant, but are here offered as an updating of his historical example. 36.Gary Fields, Working Hard, Working Poor: A Global Journey (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012), p. 46. 37.This is what Kalyan Sanyal describes as ‘need economies’. See Sanyal, Rethinking Capitalist Development. 38.The area of ‘vulnerable employment’ now accounts for 48 per cent of global employment – five times higher than pre-crisis levels.

…

, New Left Review II/84 (November–December 2013), p. 137. 101.Sukti Dasgupta and Ajit Singh, Manufacturing, Services and Premature Deindustrialization in Developing Countries: A Kaldorian Analysis, Working Paper Series, World Institute for Development Economics Research, 2006, at ideas.repec.org, p. 6; Breman, ‘Introduction’, p. 2; Fields, Working Hard, Working Poor, p. 58; Davis, Planet of Slums, p. 15. 102.Davis, Planet of Slums, p. 175; Breman, ‘Introduction’, pp. 3–8; George Ciccariello-Maher, We Created Chávez: A People’s History of the Venezuelan Revolution (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2013), Chapter 9. 103.Sassen, Expulsions, Chapter 2. 104.Sanyal, Rethinking Capitalist Development, p. 69. 105.Davis, Planet of Slums, pp. 181–2. 106.Rather than a 30–40 per cent manufacturing share of total employment, the numbers are closer to 15–20 per cent, and manufacturing now begins to decline as a share of GDP at per capita levels of around $3,000, rather than $10,000.

Carjacked: The Culture of the Automobile and Its Effect on Our Lives

by

Catherine Lutz

and

Anne Lutz Fernandez

Published 5 Jan 2010

While Crash’s Anthony is right—there remains a stigma to riding the bus in most cases—that shame could and should be transformed into pride in being environmentally responsible citizens. The ultimate goal should be to create more equality of opportunity without making additional car-dependence part of the solution. THE WORKING POOR: ONE PAYCHECK AWAY FROM CARLESS One step up from these poorest households cut off from jobs, health care, and reasonably priced goods are the working poor or near poor who, by 106 Carjacked rough estimate, include about 50 million Americans. These are individuals with low-wage jobs without benefits and families with two minimumor low-wage earners. The near poor are those who, as Katherine Newman, an expert on poverty and mobility, has said, are “one paycheck, one lost job, one divorce or one sick child away from falling below the poverty line.”7 They are one car repair or car crash away from poverty as well.

…

She gave her car to her sister. Things just got worse, though: the initial $50 ticket for the missing plate had swollen to $325. With the other fine, the new license and registration fees, it would have cost over $1,000 to get Amy back in a car, and that’s before even buying one. As with many of the working poor, a tax refund was the only thing that T H E C AT C H : T H E R I C H G E T R I C H E R 107 counted as savings, and she eventually had one large enough to show up in court that day. Amy should get a “going green” award for her use of public transit throughout that period (her husband, too: he carpooled with his boss or rode a bike to his job).

…

And of course, the company could repossess and resell the car if she missed a payment.11 Poor and working families are more likely to own older cars that guzzle gas and oil and have higher maintenance costs. Drive through any poor urban neighborhood in America and you will find a striking number of auto repair and body shops working on the old, unreliable cars that have “trickled down” to these neighborhoods. Behind these official shops are more informal but not always reliable networks: one working-poor Baltimore man, Dwayne, described his typical struggles with an older car. To afford the repairs his auto needed to get back on the road, he took it to the backyard garage of a neighbor with mechanic skills. Two weeks later, he was still badgering the neighbor to get to work on his car and scrambling for rides to work.

Tightrope: Americans Reaching for Hope

by

Nicholas D. Kristof

and

Sheryl Wudunn

Published 14 Jan 2020

The custodians in the buildings don’t have artful options like these to avoid paying taxes. Similarly, Amazon paid zero federal income tax in 2018 despite profits of $11.2 billion; indeed, it managed to get a $129 million “rebate” from taxes it didn’t pay. That’s an effective tax rate of negative 1 percent. Something is wrong with America’s tax structure when the working poor pay taxes so the federal government can make a payment to an e-commerce giant owned by the world’s richest man. Then there are the incentives for economic development awarded by states and local areas, often never made public. Oregon awarded Nike $2 billion for five hundred jobs, or $4 million per job.

…

The wealthy have also fought to underfund and defang the Internal Revenue Service, so it doesn’t have the resources to audit or fight dubious deductions. Only about 6 percent of tax returns of those with income of more than $1 million are audited, along with 0.7 percent of business tax returns. Meanwhile, there is one group that the IRS scrutinizes rigorously: the working poor with incomes below $20,000 a year who receive the Earned Income Tax Credit. More than one-third of all tax audits are focused on that group struggling to make ends meet, even as the agency cuts back on audits of the wealthy—while the top 5 percent of taxpayers account for more than half of all underreported income.

…

Friends in Yamhill often saw Trump as the outsider who would drain the swamp, bring back jobs in manufacturing and primary industries and restore a period when working-class lives were steadily getting better. Working-class voters are not uniformly conservative in their views. Polls show that they favor higher taxes on the rich, paid family leave and a higher minimum wage. But the working poor are disdainful of government benefits, even though they sometimes rely on them, partly because they often see firsthand how neighbors abuse those benefits; there’s far more anger at perceived welfare abuses than at larger subsidies for private jets. The resentment is more visceral when it is people around them who are bending rules and benefiting unfairly.

Magical Urbanism: Latinos Reinvent the US City

by

Mike Davis

Published 27 Aug 2001

The Latino educational crisis is rooted in a vicious family poverty and declining national school systems. leaving, based A commitment circle of to big city major study of the causes of Latino school- on interviews with 700 dropouts in San Antonio, EDUCATION GROUND ZERO 113 pointed to the "lack of bilingual and English as a Second Lan- guage programs, the concentration of Hispanics schools, lack of teacher preparation and panic students whole. can "^^^ testify, among in high-poverty low expectations teachers, administrators for His- and society as a In addition, as every inner-city high school counselor there are intense pressures on immigrants' teenage children (often the only citizens in the household) to supplement family incomes as soon as possible. Similarly, working poor pursue the child's classic many families of the strategy of subsidizing one education by sacrificing the schooling of others. Table 10 College Enrollment of 18- to 24- Year-Olds (Percent) Whites 1980 1990 20.8 35.9 Blacks 15.6 27.1 Asians 30.3 55.1 Latinos 14.2 22.9 Source: Marcelo Siles, Income Differentials in the Socio-Economic Development, JSRI US: Impact on Latino Working Paper No.

…

As Latinos begin to acquire majority power in the early 2000s (the retiring of the California Assembly Antonio Villaraigosa, Speaker already a de- is clared candidate for mayor), the scope for ameliorative politics will be largely defined by social investment decisions the 1980s and 1990s. Apart from jobs (and the force is made during service work- civil essentially frozen in place), the vital public resources for the working poor are education, healthcare and transit. In each instance, the future has been looted in advance. "Red Line" subway - one of the great public-works history - has devoured a generation's worth of Los Angeles's disasters in transit US investment while failing to build an extension to the Eastside and beggaring the bus system upon which most people of color depend.

…

Latinos out of told Fears, "We're "^^^ One can only hope power has become Dorn a suicidal is sincere. Locking course for African- Americans. By the same token, Latino retaliation - dispossessing Blacks of their political capital - simply works to the advantage of Giuliani and other enemies of the unity, working poor. Black and Latino however imperiled, remains the fulcrum of all progressive political change. Building Black-Latino unity is also the main challenge con- fronting Antonio Villaraigosa, the retiring left-Democrat Speaker of the California Assembly, as he prepares to run for mayor of Los Angeles in 2001.

A Framework for Understanding Poverty

by

Ruby K. Payne

Published 4 May 2012

Their circumstances demonstrate how the definition of poverty is relative to the situation." "The rise of the single-parent family has led to increased poverty among both adults and children." "Perhaps the most important factor in the increase of poverty during the 198os has been the steady decline in wage levels, so that we now have in America a group we call the working poor-people who do have jobs, who work hard, who try desperately to stay afloat as providers [for) families (sometimes men, sometimes women) but who earn such wretchedly low wages that they sink below the poverty line." Ibid. Seligman, Ben B. The Numbers of Poor. Penchef, Esther, Editor. Four Horsemen: Pollution, Poverty, Famine, Violence.

…

This inaccurate mental model is fed by media reports that favor soap operas to conceptual stories and individual stories to trends and the broader influences. The public hears about a fictitious "welfare queen" but not comprehensive studies. What is needed is a thorough understanding of the research on poverty. STUDYING POVERTY RESEARCH TO FURTHER INFORM THE WORK OF AHA! PROCESS David Shipler, author of The Working Poor, says that in the United States we are confused about the causes of poverty and, as a result, are confused about what to do about poverty (Shipler, 2004). In the interest of a quick analysis of the research on poverty, we have organized the studies into the following four clusters: ? Behaviors of the individual z Human and social capital in the community A Exploitation r Political/economic structures For the last four decades discourse on poverty has been dominated by proponents of two areas of research: those who hold that the true cause of poverty is the behaviors of individuals and those who hold that the true cause of poverty is political/economic structures.

…

The Fifth Discipline: The Art & Practice of The Learning Organization. New York, NY: Currency Doubleday. Sharron, Howard, & Coulter, Martha. (1996). Changing Children's Minds: Feuerstein's Revolution in the Teaching of Intelligence. Birmingham, England: Imaginative Minds. Shipler, David K. (2004). The Working Poor: Invisible in America. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf. Sowell, Thomas. (1998). Race, Culture and Equality. Forbes. October 5. Sowell, Thomas. (1997). Migrations and Cultures: A World View. New York, NY: HarperCollins. Taylor-Ide, Daniel, & Taylor, Carl, E. (2002). Just and Lasting Change: When Communities Own Their Futures.

Social Democratic America

by

Lane Kenworthy

Published 3 Jan 2014

American Sociological Review 69: 613–635. Drutman, Lee. 2012. “Why Money Still Matters.” The Monkey Cage, November 14. Duncan, Greg J. and Jeanne Brooks-Gunn, eds. 1999. Consequences of Growing Up Poor. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. Duncan, Greg J., Aletha C. Huston, and Thomas S. Weisner. 2007. Higher Ground: New Hope for the Working Poor and Their Children. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. Duncan, Greg J. and Richard J. Murnane, eds. 2011. Whither Opportunity? Rising Inequality, Schools, and Children’s Life Chances. New York: Russell Sage Foundation and Spencer Foundation. Duncan, Greg J., Kathleen M. Ziol-Guest, and Ariel Kalil. 2010.

…

“Wage Subsidies for the Disadvantaged.” Pp. 21–53 in Generating Jobs: How to Increase Demand for Less-Skilled Workers. Edited by Richard B. Freeman and Peter Gottschalk. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. Kaus, Mickey. 1992. The End of Equality. New York: Basic Books. Kemmerling, Achim. 2009. Taxing the Working Poor. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar. Kenworthy, Lane. 1995. In Search of National Economic Success. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. ———. 2004. Egalitarian Capitalism. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. ———. 2006. “Institutional Coherence and Macroeconomic Performance.” Socio-Economic Review 4: 69–91. ———. 2008a.

…

America’s Misunderstood Welfare State. New York: Basic Books. Marx, Ive, Lina Salanauskaite, and Gerlinde Verbist. 2012. “The Paradox of Redistribution Revisited.” Unpublished paper. Marx, Ive and Gerlinde Verbist. 2008. “Combating In-Work Poverty in Europe: the Policy Options Assessed.” Pp. 273–292 in The Working Poor in Europe. Edited by Hans-Jürgen Andreß and Henning Lohmann. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar. Mayer, Susan E. 1999. What Money Can’t Buy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Mayer, Susan E. and Christopher Jencks. 1993. “Recent Trends in Economic Inequality in the United States: Income versus Expenditures versus Material Well-being.”

Age of the City: Why Our Future Will Be Won or Lost Together